As Teiresias passes along the parados led by a silent boy into the

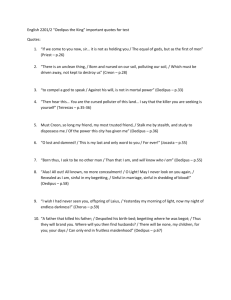

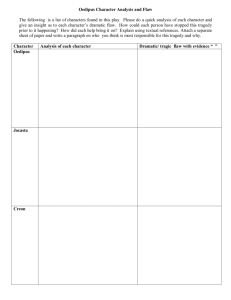

advertisement

As Teiresias passes along the parados led by a silent boy into the orchestra the Chorus warn Oedipus of his approach calling him, ... our god-like prophet, in whom the truth resides more so than in all other men. Oedipus too welcomes the seer and praises his gift Teiresias, you who understand all things ... our shield and saviour. With all this build-up Sophocles cleverly set us (the audience) up to expect a zen-like Yoda figure to expound upon the mysteries of Fate but instead Teiresias’ first words are an anticlimax for he appears rather as an old man weighed down by sorrow and anxiety. Alas, alas! How dreadful it can be to have wisdom when it brings no benefit to the man possessing it. Teiresias is initially determined not to reveal the answers to the riddling oracles demands because he knows that it will cause pain for those concerned and more so because he knows that no one can escape destiny – what will be, will be. Yet events will still unfold, for all my silence. We must understand Sophocles’ motivations here. In this agon (confrontation) it is vitally important for the poet to present both sides of the argument. Teiresias takes no pleasure in his knowledge of the future, just as Oedipus takes no pleasure in his ignorance of it. Oedipus’ rage is understandable in this sense because he is so desperate to solve the murder of Laius that he sees the seer’s refusal to help, when he is seemingly able, as an act of treason. Do you intend to betray me and destroy the city? Oedipus next loses his temper and insults the prophet. You most disgraceful of disgraceful men! But ever conscious of the dramatic effect of his lines, Sophocles next endows Teiresias with a cynical wit and the courage to stand up to the king and he also begins to set us up for the paradox that will come at the end of the scene. Here he alludes to (hints at) Oedipus’ blindness or ignorance despite his seeming insight or wisdom. You blame my temper, but do not see the one which lives within you. Instead, you are finding fault with me. Thus stung by the prophet’s retort Oedipus loses control and gives way to his irrational paranoia. He starts to jump to conclusions, rather than examining the evidence as he said he would in the beginning. Were there any proof beyond Teiresias’ refusal to reveal the truth, it would not be irrational to suggest that Teiresias had conspired to kill Laius himself but since Oedipus does not question Teiresias’ reluctance but nonetheless accuses him of treason there can be little doubt that Oedipus is clearly groping in the dark of his own rage and fear. I get the feeling you conspired in the act, and played your part, as much as you could do, short of killing him with your own hands. If you could use your eyes, I would have said that you had done this work all by yourself. Oedipus also begins to mock the prophet’s blindness but Teiresias is able for his assault and counters with every bit as much venom as Oedipus by revealing that which he had initially refused. The difference of course is that Teiresias has the truth on his side and his blows are measured, albeit by anger; for Teiresias is angry. Oedipus’ on the other hand is ranting in blind rage and he lashes out at the prophet in blind and aimless abuse. Is that so? Then I would ask you to stand by the very words which you yourself proclaimed and from now on not speak to me or these men. For the accursed polluter of this land is you. In the next few lines we see Oedipus availing of the tricks of basic rhetoric (the skill of arguing) as he asks Teiresias to repeat his accusation three times in a bid to have the prophet completely ruin himself publically by his perceived treachery. The irony of the situation is not lost on us. Were this just a tirade of abuse we would view Oedipus’ tactics as wise but given that Teiresias is a prophet, and trusting in the power of prophecy in Greek mythology as we do, we are painfully aware of Oedipus’ hybris (arrogance). Oedipus does not believe in prophecy and thinks himself in control, when tragically it is Teiresias who has the upper hand. Sophocles is also clever to make sure our sympathies in this scene rest with Teiresias for he is an old blind man who is being abused and threatened by a man who should behave better than he does. Oedipus’ final insult rings with contempt. Truth is not in you— for your ears, your mind, your eyes are blind! To which Teiresias unmasks Oedipus as a “wretched fool” and as to the perceived threat he poses to Oedipus he assures the king that he has nothing to fear from him but instead should fear him for whom he speaks. This is the first time Apollo has been mentioned by name in the agon. This is telling, as is what Teiresias says. It is not your fate to fall because of me. It’s up to Apollo to make that happen. He will be enough. Oedipus next jumps to his wildest conclusion – that Creon conspired with Teiresias to murder Laius – for which there has been absolutely no evidence apart from Oedipus’ assertion that if the blind man did conspire against him he must have had help because he is blind and could not work alone. Again Teiresias’ response strikes at the nub of the whole tragedy. Creon is no threat. You have made this trouble on your own. As we will see later neither Apollo nor anyone else did the deeds for which Oedipus will be cursed. Oedipus himself did those deeds but for now he must come to realise this fact before realising that Apollo was behind it all from the very beginning. Next Sophocles puts Oedipus to the task of revealing his suspicions. Like a broken Sherlock Holmes, the detective reveals the intrigue. Creon being jealous of Oedipus’ power hired this “quack” who is blind in prophecy like he is blind in sight to slander Oedipus with the outrageous crimes of parricide and incest – for which if guilty, he would be forced to abdicate. As proof of Teiresias’ fraud Oedipus asks a very pertinent question and one which Sophocles doesn’t examine further in the play. When the Sphinx, that singing bitch, was here, you said nothing to set the people free. Why not? But Oedipus goes on now to show his true colours and in the final insult we realise that we can now add insincerity to Oedipus’ long list of faults. He welcomed the prophet initially and praised his gift but now he shows clearly that he does not believe in augury (soothsaying). Her riddle was not something the first man to stroll along could solve—a prophet was required. And there the people saw your knowledge was no use— nothing from birds or picked up from the gods. But then I came, Oedipus, who knew nothing. Yet I finished her off, using my wits rather than relying on birds. Next the Chorus intervene to ask both men to calm down saying that a fight is not what is needed. Teiresias now claims the right to defend his good name and begins to plant the seeds of doubt in Oedipus’ mind by questioning all the things he takes for granted as true: his parents, his native land, his wife and children. Each will systematically haunt Oedipus as he gropes through the darkness of his life and solves the mystery for now Sophcoles contents himself in reveals the irony of Oedipus’ tragic situation to us, which is ingenious because from now on the play will hand on suspense. Sophocles deliberately keeps us one step ahead of Oedipus. So I say this to you, since you have chosen to insult my blindness— you have your eyesight, and you do not see how miserable you are, or where you live, or who it is who shares your household. Oedipus now seeks to extricate himself from the argument by dismissing the prophet. The weakness of his position is not lost on us. He reminds us of a bully who on the verge of losing face before a crowd begins to insult his victim and walk away with his cronies. Yet Teiresias will not be beaten. In fact he’s on fire. The last exchanges are fraught with double meaning and black wit. Oedipus: Off with you! Now! Turn your back and go! And don’t come back here to my home again. Teiresias: I would not have come, but you summoned me. Finally, Teiresias defends his blindness and his skill by telling Oedipus that his parents were happy enough with him to which Oedipus grasps furiously. Wait! My parents? Who was my father? But Sophocles is not ready to reveal this yet. Instead Teiresias departs with is head held high having kept his respect. He has no more time for mincing words with Oedipus. He simply says, This day will reveal that and destroy you. Oedipus can’t let it go however. It’s as if he has to have the last word on everything and Teiresias likewise is the same. Neither men can leave it as it is. They have to end on a high note. Oedipus accuses the prophet of speaking in riddles, which is far too tempting a dish for the seer to refuse because Oedipus prides himself as the riddle solver. Oedipus waves him away with threats of violence. Teiresias has all the time being trying to leave and when he finally saks the boy to guide him away Oedipus, like a coward, shouts after him. This act, of all the ones that came before, is what stings the prophet the most and when he wheels around he does what he swore he would not. He reveals the full truth and perplexes the Chorus. Sophocles cleverly has Teiresias refer to the murderer in the third person (he) not naming Oedipus. We know of course that Oedipus is the murderer because Teiresias has already said so earlier but here Sophocles acknowledges that Oedipus himself has not accepted this yet, so he is still on the hunt for a mysterious murderer. He will prove to be native Theban and both husband and son to his wife and mother and brother and father to his children. The double irony however is that he will end up suffering all of the things he jeered Teiresias for earlier. He will be blind, although he now can see. He will be a poor, although he now is rich. He will set off for a foreign country, groping the ground before him with a stick. Exit Teiresias CREON Creon’s role is varied in the plot because he appears three times during the course of the play. He has a dual function in his first appearance at the beginning of the play. First he acts as a messenger moving the plot along by news from outside; in this case Delphi. Even from his very first appearance in the play, Creon strikes us as diplomatic – a born statesman. Seeing Oedipus surrounded by the people he is deliberately slow to publish the oracle when asked by Oedipus. Good news. I tell you even troubles difficult to bear will all end happily if events lead to the right conclusion. His reply is deliberately vague and when asked a second time by Oedipus who clearly hasn’t taken the hint we learn why. If you wish to hear the news in public, I’m prepared to speak. Or we could step inside. Creon wants to go inside because the oracle as we learn will force Oedipus’ hand should it become public straight away. Oedipus again gives him leave to speak revealing himself as a man of the people but his democratic attitude is misplaced. He should have trusted Creon but Oedipus clearly lacks Creon’s tact. Creon is forced to publish the oracle. Lord Phoebus clearly orders us to drive away the polluting stain this land has harboured— which will not be healed if we keep nursing it. Oedipus again puts his foot in it when he asks Creon what the oracle demands they do about this polluting stain. Creon again has no choice but to lay his cards out in full. By banishment or atone for murder by shedding blood again. This blood brings on the storm which blasts our state. Whatever happens now, Oedipus will be forced to solve the murder of Laius and either banish the culprit or kill him by order of the oracle of Apollo. On the face of it this seems straight forward enogh but later on when he realises the truth, how dearly he might wish that he had brought Creon indoors here because now the Chorus of Theban Elders know the gods’ commands. The entire play is now framed by that command. His second role in the first scene is as a secondary narrator filling us in on the backstory of the play. He is questioned by Oedipus about Laius, the sphinx, her riddle, Laius’ trip to Delphi, his mysterious disappearance and Oedipus eventual victory over the Sphinx and his coronation and marriage to Jocasta. Most importantly, it is Creon that reveals Laius was killed in an ambush by a band of thieves on the road to Delphi and that one man escaped to tell the tale but that he ran away. His third appearance is in an agon (confrontation) with Oedipus when he comes to defend his good name against the unproven charge of treason with Teiresias. In this agon we are presented with two extreme opposites ranged against each other. Creon is a man of reason whereas Oedipus is a man of passion. As any good man would, Creon comes to defend his good name having heard that Oedipus has slandered him as a traitor. The Chorus who have just witnessed Oedipus’ descent into passionate fury against Teiresias tell Creon that Perhaps he charged you spurred on by the rash power of his rage, rather than his mind’s true judgment. Creon’s main concern seems to be what they think – the people. Was it publicized that my opinions convinced Teiresias to utter lies? When he learns what has gone on behind his back he inquires further as to the circumstances. Did he accuse me and announce the charges with a steady gaze, in a normal state of mind? But he gets nowhere because the Chorus claim ignorance I do not know. What those in power do I do not see. But he’s approaching from the palace— here he comes in person. Creon is clearly a man obsessed with how he appears in public. On the one hand we might view this as vanity but on the other it can be viewed as noble because Creon, unlike Oedipus, is aware that the people’s hopes hinge on how their ruler’s behave in public and how they appear in the public’s mind. When Oedipus arrives he wastes no time in re-iterating the accusations against Creon and demands to know how he dared to think he would succeed in such treachery. Remember Oedipus departed at the end of the first scene. We might expect him to have calmed down a little but no. As soon as he sees Creon he verbally springs upon him showing that he has lost nothing of the temper with which he insulted the prophet in the previous scene. Creon on the other hand appears calm and level headed. His response to Oedipus tirade is short and measured. Will you listen to me? It’s your turn now to hear me make a suitable response. Once you know, then judge me for yourself. Oedipus’ next words are meant as a rebuke but carry a double meaning too. You are a clever talker. But from you I will learn nothing. Oedipus will not learn anything from Creon because he will not listen to him, which is Creon next request. He will not see reason because he has given way entirely to passion and to a paranoid delusion that Creon is out to get him. He demands Creon to one thing – admit his guilt. For the third time Creon begs the king to see reason and to calm down. If you think being stubborn and forgetting common sense is wise, then you’re not thinking as you should. But it is useless. Oedipus will not be moved, so instead Creon changes tactic. He invites Oedipus to issue his accusations freely, which Oedipus is only too ready to do. In fact, that is all Oedipus wants to do. Oedipus has not come to talk but to sentence Creon. Here the agon takes on the look of a court case with the chief prosecutor Oedipus conducting his examination-in-chief with the chief witness for the defence: Creon. Creon answer truthfully and openly and Oedipus only get through one question before pausing mid sentence as if something has suddenly occurred to him. How long is it since Laius . . . Oedipus does not explain why he pauses but we can guess that the wheels of fate are already turning the cogs in his memory and he is beginning to realise. Regardless, Oedipus carries on blindly, stubbornly, pathetically trying to win an argument he has already lost by his demeanour. During his examination he poses the same question he posed rhetorically to Teiresias – the one we want to know the answer to – about Teiresias’ failure to rid the city of the Sphinx. Why did this man, this wise man, not speak up? Creon’s reply is both honest and clear but also damning for Oedipus. I do not know. And when I don’t know something, I like to keep my mouth shut. Oedipus ends his examination with an accusation that Creon conspired with Teiresias to usurp the throne but since the onus of proof rests with Oedipus and since Creon will admit nothing, nor has Teiresias Oedipus has come to a dead end whether he likes it or not. Creon next turns the tables and begins to cross-examine Oedipus. Having answered all his questions Oedipus cannot deny him the right but he begrudges him this sense of fair play. Ask all you want. You’ll not prove that I’m the murderer. Of course Creon is not trying to prove anything but his own innocence but Oedipus has missed that point because he can’t think clearly. Creon proceeds to disseminate Oedipus’ conlusions by showing the folly in his ambition to rule when he already shares equal power with Oedipus and Jocasta save for the stress attached to being king. Having the best of both worlds he therefore invites Oedipus to travel to Delphi and ask the oracle if he delivered the news faithfully. His final plea is the most damning. He says, Do not condemn me on an unproved charge. It's not fair to judge these things by guesswork, to assume bad men are good or good men bad. ... Give it some time. Then you’ll see clearly, since only time can fully validate a man who’s true. A bad man is exposed in just one day. The Chorus now intervene on Creon’s behalf urging the king to see reason and accept the truth behind Creon’s argument but Oedipus remains unflinching in his untenable conviction that Creon is a traitor and goes further than the bounds of expectation in revealing his wish to have Creon executed. Oedipus has over-reacted again. He did so in the beginning when he cursed the murderer. Now he does so again and again his over-reaction comes as a result of being caught by the passion of the moment. Oedipus is a slave to his emotions. They control him. They do not control Creon. Creon next accuses Oedipus of insanity and in replying Oedipus reveals something shocking about his character. CREON What if you are wrong? OEDIPUS I still have to govern. CREON Not if you do it badly. OEDIPUS my city! Oh Thebes— The irony of Oedipus’ last line here not lost on us. Oedipus is a native Theban. More so however this line is damning. Oedipus blindly considers Thebes his city and his rule of the city a right onto himself. This is vanity. Oedipus is a vain man who lacks the tact with which to rule – tact that Creon possesses. He lacks the care to rule well because he will rule no matter the consequences of his actions. He doesn’t even have a conscience about his actions because he is king and that in his view gives him the right to do whatever he chooses with the sanction of law. The rule of Thebes is all about him, not the people. It is for this reason that he spares no thought, as Creon does, for how he behaves publically, as long as he seems like a just king. We might see Creon and Oedipus’ obsession with appearance as similar only for the fact that Oedipus’ is motivated by insecurity, fear and paranoia. Creon on the other hand is motivated by a noble heart, level headed pragmatism and a thorough grasp of politics. We see here that Sophocles named this play well for contrary to the general translation Oedipus Tyrannus does not simply mean Oedipus The King. It means Oedipus The Tyrant and a tyrant is a despotic, cruel and careless ruler, which is what Oedipus has just revealed himself to be. Contrary to how he appeared in the beginning, Oedipus does not really care about the Thebans. He only cares about himself. He is motivated by self-interest in practically every respect. Creon on the other hand is not. He does care for the city and for himself. In defending himself and his good name he has defended free speech and championed reason over blind passion. He has won. We respect Creon as does the Chorus. The agon is brought to a swift close by Jocasta and a stalemate is declared. Creon goes into exile. Oedipus refuses to make peace with him and admits that the only reason he does not kill him is for the sake of the Chorus who asked him to do so. As Creon leaves he echoes our feelings on the matter. I’ll leave— since I see you do not understand me. But these men here know I’m a reasonable man. When Creon returns at the end of the play he takes no pleasure in his vindication and magnanimously assures Oedipus tha he has not come to mock him or to gloat. Again he shows his concern for appearances when he says, But if you can no longer value human beings, at least respect our lord the sun, whose light makes all things grow, and do not put on show pollution of this kind in such a public way, for neither earth nor light nor sacred rain can welcome such a sight. As always, Creon shows deference to the gods and refuses Oedipus’ request for banishment until such time as the oracle can be consulted. Oedipus challenges this stance to which Creon repeats something of what he said before, I don’t like to speak thoughtlessly and say what I don’t mean. Finally, Oedipus begs for his daughters to be left in his custody to which Creon respond with the force of a king and orders him to accept the reality of his situation. Don’t try to be in charge of everything. Your life has lost the power you once had. Things have now come full circle. Creon has taken over from Oedipus and Oedipus is overthrown, surely soon to be banished. We can view Creon as a positive victim of tragic irony in this respect. Creon never wished for any of this but by obeying the gods in every minute detail he is rewarded, whereas Oedipus who through hybris attempted to escape his destiny is punished utterly for it.