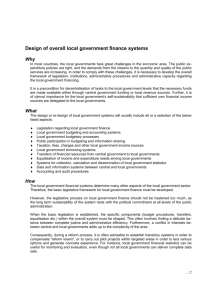

Full Text (Final Version , 367kb)

advertisement