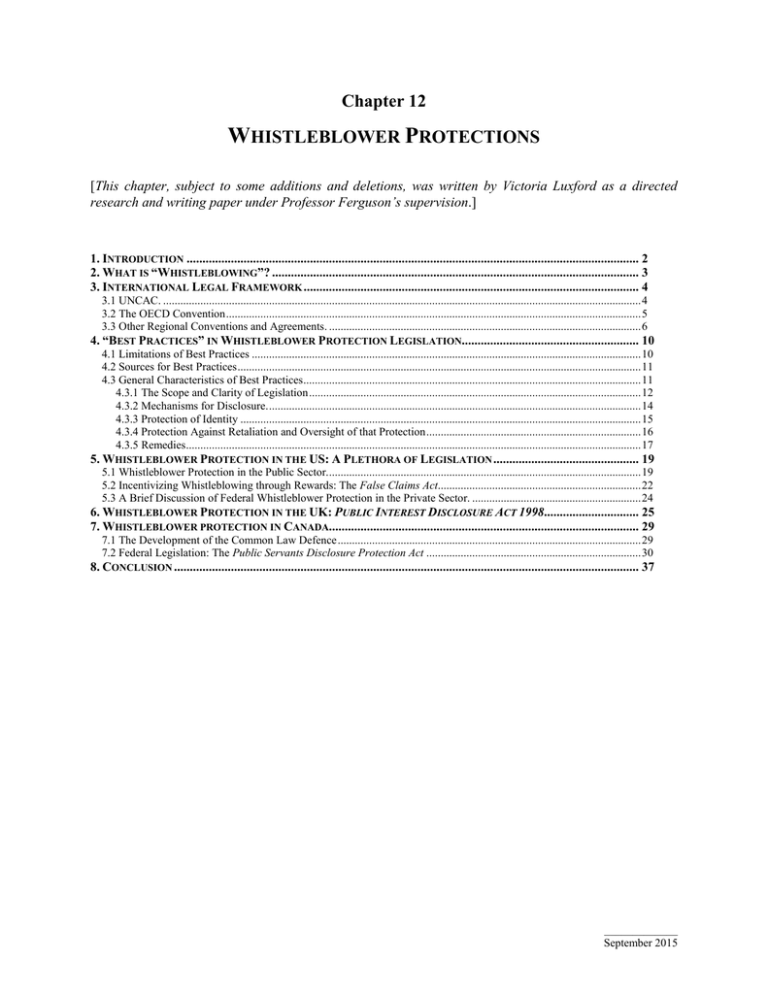

Chapter 12 - Tools and Resources for Anti

advertisement