Institutional Integrity -- Speaking Truth to Power

advertisement

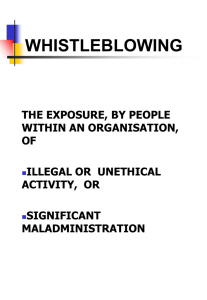

Institutional Integrity- Speaking Truth to Power (speech given by Coleen Rowley at NASA Legal Conference, 4/29/2004, in New Orleans, Louisiana) Other than what I’ve read in newspapers, I know nothing about the launching of space shuttles or the other inherently risky business that NASA engages in. But in reading portions of the (very insightful!) Columbia Accident Investigation Board’s Report, I was struck by the similarity of some of the negative group-think and management factors that are endemic and common to another risky business that I’m more familiar with, that of attempting to prevent future acts of terrorism, and which (if my study this last year is accurate of a variety of other “whistleblowing” cases), actually seem to be endemic among so many, if not most, professional tasks. I suppose the reason for these parallels or (as the Report terms them) “echoes” is rooted in human nature but hopefully the discussion and better understanding of the fallibilities we are most prone to, will give us some measure of controlling and minimizing the potential for these foibles to play out and lead to further problems and sometimes disaster. I was struck by the following similarities between the history of what happened in both the Challenger and Columbia tragedies and what at least in part was responsible for hampering our investigation/disruption of the 9-11 terrorists. Essentially what you have in all of these (for lack of a better term) “whistleblower” type cases (and in so many others- i.e. CIA analyst Sam Adams disputing Vietcong troop strength during Vietnam War; the priest who in 1985 uncovered the scope of the priest-pedophile problem, the leak of chemicals into ground water in California; and nuclear safety whistleblowers) is the little guy(s), who don’t have much clout or power in the organization but who do have the technical expertise or the facts (truth) and who then desperately try, many times unsuccessfully to raise their issue up the chain to a level which has the power to do something about the problem. Many times, in their desperation, the little guys try skipping a rung or two (over the perceived roadblock) or even “going outside” their chain of command in order to get the attention of person or persons who they hope might be more receptive. Unfortunately, in these scenarios, there are too many unhappy endings: many times the little guy is unsuccessful in convincing the higher-ups and either gives up or time runs out. The disaster and/or scandal is not prevented or minimized. The little guy blames him/herself for a long time for not having tried harder or earlier (i.e. Daniel Ellsberg, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Roger Boisjoly, and Sam Adams). Even when the little guys are listened to and remedial actions/changes made, the situation is such that no one can then ever know or prove what, if any, damage/tragedy was averted so, many times, the little guy is blamed for the extra expense/trouble and sometimes, as a consequence, loses his job/friends, etc. So what are the issues and obstacles endemic to these scenarios? 1) There is rarely a “silver bullet,”- that is there is rarely just one isolated fact or remedy that alone would be determinative of the hoped-for outcome. There is rarely an “answer” and an inordinate focus on the “answer” (the result) obscures the concrete steps (the means) to improvement. The series of things that have to come together to alleviate the problem and/or prevent/diminish the tragedy also serve to diffuse responsibility; 2) The 20/20 hindsight problem; true countervailing risks and costs of “false positives” (i.e. the truth is unpleasant about the impossibility of preventing ALL jail suicides; preventing ALL acts of terrorism; preventing ALL accidents/disasters when operating a risky business so we tend to prefer to gloss over this unpleasant truth. We make promises or slogans that are not realistic and then become hypocrites worrying when 20/20 hindsight is applied.); 3) Conflicts of interest and careerism. (i.e. the Linda Ham and Arthur Anderson problem. The good news is there are ways to regulate and structure things to combat some of these problems if we are realistic about the role this factor plays. For example, accounting companies like Arthur Anderson allowed to make money from consulting as well as auditing; the revolving door with government hierarchy and even the making of money from writing books/speechmaking after government service impacts one’s current ability to put the client or the public first); 4) Reluctance to change and/or recognize a problem. Many concerns bring up or tie in with larger issues requiring larger and more difficult systemic improvement and it’s far easier for the Emperor to try to just keep marching. (i.e. the failure of the FBI to computerize b/c agents didn’t type and didn’t want to learn); 5) Profit/greed/budget constraints. Even though actual profit/greed doesn’t loom as large a force in the government sector as in the private one, it’s still a big factor, and exerts an influence on decisionmaking; 6) “Whistleblower” perceived as trouble maker- the conflicting loyalties problem; 7) Group think- Asch test conformity and obedience issues- (i.e. whistleblower’s fear of being ridiculed); 8) Pettifoggery or the incremental nature of mistakes/wrongdoing; and 9) Uselessness of trying/hopelessness is HUGE - (i.e. rescuing the astronauts on board the Columbia which would have required an extraordinary effort, timing and spacewalk; “preventing 9-11” would have been very difficult if not impossible). However that is simply not the issue. We must TRY and with a little luck, no one knows the outcome. I. INTEGRITY- simply defined is “doing right when there is no one to make you do it but yourself” (Judge John Fletcher Moulton as quoted by Edwin Delattre, Police Leadership Forum, Nov. 1997) II. Doing right. Step 1 Discernment: Determine what is the right thing to do. This is relatively easy when a contemplated action is clearly criminal (i.e. illegal drugs) or violates a clear ethical mandate (i.e. lying) or when the action is clearly right because it’s legal and beneficial (i.e. helping others; following “golden rule”). However there is a gray area between right and wrong where competing interests sometimes result in “ethical dilemmas” (examples/problems involving moral relativism). We should be willing to devote enough thought and reflection, if need be, in consultation with other authorities, however, to make the gray area of moral relativism as thin a line as possible. Step 2 Action: Summon the courage to try to do the right thing. Just like Step 1 (making the determination) this can be easy or very hard (e.g. going against peer pressure; example of Unabomber Ted Kaszinsky’s brother contacting law enforcement). Ethical decision making in context of distinguishing “tattletaling” vs. “whistleblowing” (cartoon)- at least four criteria should be met: 1) Issue must be significant (i.e. classmate telling on another classmate, “he stole my pencil” as opposed to Columbine type situation of overhearing a classmate threaten to bring weapons to school). 2) Must be truthful and essentially right, despite the fact that in many cases there is no way of anyone having that type of perfect intelligence or completely knowing all of the pertinent facts (e.g. example of Challenger Shuttle explosion due to o-ring sealing failure). 3) Motivation- must not be to promote self interest but interest of others or the public. 4) Must be done in the most constructive, (not destructive) way. Step 3 Act openly and talk about it: But must be more than lip service (i.e. Enron’s Code of Ethics/ Kenneth Lay’s foreward/ Enron napkins with Dr. Martin Luther King quote, “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”) a) Promotion of institutional integrity, so that all employees feel free, even obligated, to do the right thing, even if it has a short-term cost. “Integrity in the public service also imposes on public servants, at all levels, a commitment to the truth and therefore, an obligation to speak truth to power: to provide ministers and other supervisors with a full range of analysis and advice that will help them to take the best possible decisions for the public good.” (John Tait, A Strong Foundation: CCMD Study Team on Public Service Values and Ethics. Dec. 1996 pgs 34 and 72)