Parent's Manual

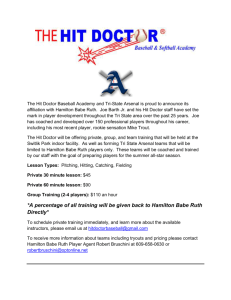

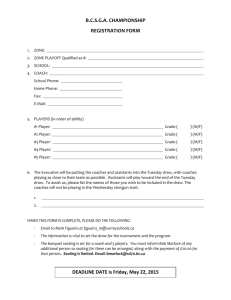

advertisement