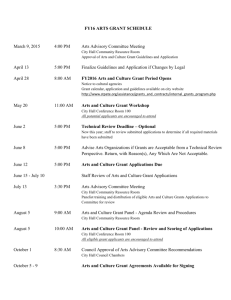

Grants Review - Department of Finance

advertisement