Managing conflicts of interest in the UK National Institute for Health

advertisement

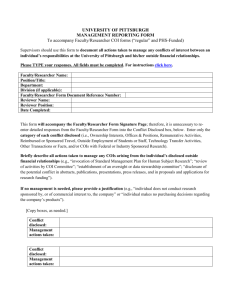

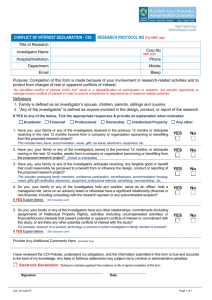

Are clinical guidelines trustworthy? Managing conflicts of interest in the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical Guidelines Programme Tim Stokes, Phil Alderson (NICE), Tanya Graham (King’s College, London) My declaration of interest (ICMJE) • Tim Stokes is employed by the University of Otago and works clinically as a salaried General Practitioner • He has not received any personal funding from industry groups for research, consultancy or travel • He has received over the last 36 months an honorarium from one pharmaceutical company paid into a University of Birmingham (UK) school account for speaking about NICE's work programmes in the UK in 2013 BMJ 2013;347:f6989 Outline • Background – Study aim • Methods • Results • Conclusions BACKGROUND Conflicts of interest (COI) • Definitions – “set of conditions in which professional judgement concerning a primary interest (such as a patient’s welfare or validity of research) tends to be unduly influenced by a secondary interest (such as financial gain).” • Thompson DF. Understanding financial conflicts of interest. N Engl J Med 1993 August 19;329(8):5736. – Financial versus non-financial – From whom? • Big Pharma; Food, alcohol and tobacco groups; Health care industry and providers – Where? • Clinical Trials; Systematic Reviews; Guidelines; Ethics Committees …. Why does it matter? • Important source of bias Odierna DH, Forsyth SR, White J, Bero LA. The Cycle of Bias in Health Research: A Framework and Toolbox for Critical Appraisal Training Account Res. 2013 ; 20(2): 127–141. doi:10.1080/08989621.2013.768931. What effect does it have? • Industry-funded studies are likely to produce findings that: – favour the sponsor’s intervention or that support public health policies that benefit the funder • Cochrane review • pharmaceutical industry sponsored studies overestimate the efficacy and underestimate the harm of their treatments – even when controlling for methodological biases White J, Bero LA. Corporate manipulation of research: Strategies are similar across five industries. Stanford Law & Policy Review. 2010; 21(1):105–134. Lundh A, Sismondo S, Lexchin J, Busuioc OA, Bero LA. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Dec 12.2012 12 MR000033. doi:10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub2. Lundh A, Sismondo S, Lexchin J, Busuioc OA, Bero LA. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Dec 12.2012 12 MR000033. doi:10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub2. How should we tackle it? • Self Regulation – Self disclosure and codes of conduct • Mandatory (legal) disclosure – Physician Payment Sunshine Act (PPSA) US 2010 • It covers all manufacturers of drugs, devices, and biological and medical supplies covered by federal health care programs and will require the tracking of all financial relationships with physicians and teaching hospitals • September 2014 – first data published: – 4.4 million payments totaling $3.5 billion and more than half a million US doctors and about 1,360 teaching hospitals received at least one payment (not including continuing medical education payments). https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/index.html Clinical Guideline development • Financial COI among guideline group chairs and members: – are common and ? under-reported • US and Canada (CGs 2000-2010) – 52% of panel members had financial COI (92% declared) – Panel members from government sponsored guidelines were less likely to have conflicts of interest compared with guidelines sponsored by non-government sources (15/92 (16%) v 135/196 (69%); P<0.001 Neuman J, Korenstein D, Ross JS, Keyhani S. Prevalence of financial conflicts of interest among panel members producing clinical practice guidelines in Canada and United States: cross sectional study. BMJ 2011;343:d5621. • Europe (Denmark 2010-2012) – 53% of panel members had financial COI (2% declared) Bindslev JB, Schroll J, Gotzsche PC, Lundh A. Underreporting of conflicts of interest in clinical practice guidelines: cross sectional study. BMC Med Ethics 2013;14(1):19. Clinical Guideline development • COI can directly influence the development of clinical guideline recommendations: • Case study of two guidelines on ITP – One pharma funded – ICR - (16 panel members out of 22 reported associations with pharmaceutical companies) – One Medical Society funded (Am Soc Haematology) » Members: Content Expertise PLUS had to have lack of financial COI – Discrepancies were conspicuous when the guidelines addressed treatment – In contrast to the ASH guideline, the ICR gave stronger recommendations for agents manufactured by companies from which the ICR or its panel members received support George JN, Vesely SK, Woolf SH. Conflicts of Interest and Clinical Recommendations: Comparison of Two Concurrent Clinical Practice Guidelines for Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia Developed by Different Methods. Am J Med Qual 2013 April 2;20:1-8. Why it matters? • Clinical guidelines are: – “recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options” – one of the key foundations for quality improvement in health care – International consensus is that guidelines should be developed using an explicit and transparent process Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011 Mar 23. How do we develop clinical guidelines? 1. Identifying and refining the subject area of a guideline 2. Obtaining and assessing the evidence about the set of key clinical questions (PICO): – Evidence reviews: Rapid SRs • A technical process Eccles M and Mason J. How to develop cost-conscious guidelines. Health Technol Assess 2001;5. How do we develop clinical guidelines? 1. Identifying and refining the subject area of a guideline 2. Obtaining and assessing the evidence about the set of key clinical questions (PICO): – Evidence reviews: Rapid SRs • A technical process 3. Convening and running guideline development groups - chair; clinical experts; lay members; methodologists 4. Translating the evidence into recommendations (clinical guideline) • A social process 5. Arranging external review of the guideline - Process takes 18 months How to reduce COI bias in clinical guideline development? • Self regulation – development and implementation of policies that: • Address the disclosure of COI by guideline group members • give clear guidance on how such COI should be handled during guideline development – Such policies are in general use internationally • NICE has had a COI policy since 2004 Norris SL, Holmer HK, Burda BU, Ogden LA, Fu R. Conflict of interest policies for organizations producing a large number of clinical practice guidelines. PLoS One 2012;7(5):e37413. Summary of NICE COI Code of Practice as it relates to clinical guidelines (2007) Definition of types of COI personal pecuniary interest involves a current (within the last 12 months) personal payment, which may either relate to the manufacturer or owner of a product or service being evaluated, in which case it is regarded as ‘specific’ or to the industry or sector from which the product or service comes, in which case it is regarded as ‘non-specific’. A non-personal pecuniary interest involves payment or other benefit that benefits a department or organisation for which an individual has managerial responsibility, but which is not received personally. This may either relate to the product or service being evaluated, in which case it is regarded as ‘specific,’ or to the manufacturer or owner of the product or service, but is unrelated to the matter under consideration, in which case it is regarded as ‘non-specific’. A personal non-pecuniary interest in a topic under consideration might include, but is not limited to: i) a clear opinion, reached as the conclusion of a research project, about the clinical and/or cost effectiveness of an intervention under review ; ii) a public statement in which an individual covered by this Code has expressed a clear opinion about the matter under consideration, which could reasonably be interpreted as prejudicial to an objective interpretation of the evidence; iii) holding office in a professional organisation or advocacy group with a direct interest in the matter under consideration; iv) other reputational risks in relation to an intervention under review. A personal family interest relates to the personal interests of a family member and involves a current payment to the family member of the employee or member. The interest may relate to the manufacturer or owner of a product or service being evaluated, in which case it is regarded as ‘specific’, or to the industry or sector from which the product or service comes, in which case it is regarded as ‘non-specific’. Declaration of COI The chair and members of the guideline development group (GDG) need to declare any COI on appointment to the GDG, annually and at each guideline development group meeting. Action to be taken in response to COI: At appointment to GDG The chair the GDG must divest him/herself from any personal pecuniary interest on appointment, or as soon as practicable afterwards At GDG meetings Personal specific pecuniary interest: Declare and withdraw Personal non-specific pecuniary interest: Declare and participate (unless, exceptionally, the chair rules otherwise) Personal family specific interest: Declare and withdraw Personal family non-specific interest: Declare and participate (unless, exceptionally, the chair of the advisory body rules otherwise) Non-personal specific pecuniary interest: Declare and participate, unless the individual has personal knowledge of the intervention or matter either through his or her own work, or through direct supervision of other people’s work. In either of these cases he or she should declare this interest and not take part in the proceedings except to answer questions Non-personal non-specific pecuniary interest: Declare and participate (unless, exceptionally, the chair of the advisory body rules otherwise) Personal specific non-pecuniary interest: Declare – action is at discretion of the chair This study • Arose out of an audit of NICE’s COI policy – Quantitative & qualitative – 2012 • How are such policies interpreted and used by guideline producing organisations? • very limited published research – Neumann I, Karl R, Rajpal A, Akl EA, Guyatt, GH. Experiences with a novel policy for managing conflicts of interest of guideline developers: a descriptive qualitative study. Chest 2013 August;144(2):398-404. Study aim • To determine how conflicts of interest (COIs) are disclosed and managed by a national clinical guideline developer (NICE) using qualitative methods What NICE produces 180 Medical devices Quality standards Public health 160 Interventional procedures 140 120 100 Quality and outcomes framework (QOF) Clinical guidelines CG187 latest Oct 2014 NHS Evidence accreditation Diagnostics 80 Technology Appraisals 60 40 20 0 2000/1 2001/2 2002/3 2003/4 2004/5 2005/6 2006/7 2007/8 2008/9 2009/10 2010/11 Mar-Oct 2011 NICE How NICE develops guidelines NATIONAL COLLABORATING CENTRES (NCCs) National Guidelines Centre Clinical Guidelines with independent chairs NCC Womens and Children’s Health Clinical Guidelines with independent chairs NCC Mental Health Clinical Guidelines with independent chairs NCC Cancer Clinical Guidelines with independent chairs NCC Internal Guidelines Programme Clinical Guidelines with independent chairs Methods • Qualitative study – Research Ethics Committee approval in the UK was not required – semi-structured telephone interviews with 14 key informants: • Sampled purposively (all major clinical areas) – 8 senior staff of NICE’s guideline development centres (NCCs) – 6 chairs of guideline development groups (GDGs) » guidelines published within the previous 2–3 years as these would have followed the current NICE code of practice for declaring and dealing with conflicts of interest Methods • Qualitative study – semi-structured telephone interviews with 14 key informants: • Semi-structured telephone interviews – Between April and June 2012 • Interviews audiotaped (not transcribed) • Halcomb EJ, Davidson PM. Is verbatim transcription of interview data always necessary? Appl Nurs Res 2006 February;19(1):38-42. – thematic analysis • Using framework analysis method – Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. London: Sage; 2003. – Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013 September 18;13(1):117. Results • Two main themes – Identifying conflicts of interest – managing conflicts of interest Results (2): Identifying COI • Self reporting – Both chairs and NCC senior staff talked about medical practitioners being unaware that their activities constituted a COI: – If you give a talk at [a specialist medical society] you have to put up a slide with your COI. When I put a slide of my conflicts – others are amazed and nobody else has any declarations of interest ... most speakers had a conflict but didn’t recognise that they had one. [NICE guideline chair, I12] – Several chairs highlighted the fact that the process of applying for and being appointed chair of a NICE committee made them realise how important COI were in the context of developing clinical guidelines Results (3): Identifying COI • What constitutes a COI – Pecuniary interests relatively easy to identify • e.g., share holding or paid pharmaceutical advisory board meetings – non-pecuniary COIs and in particular research activities were seen as both widespread and also difficult to assess in terms whether or not they constituted a COI: • Non- pecuniary personal [interests] are most difficult because it is about anything you have been outspoken about – if they publish as most academics do or do research about it you will have been outspoken about a particular treatment. [Senior Staff NCC, I3] Results (4): Managing COI • Disclosure of COI – relies on self reporting of members NCCs had to take “on trust” the information they received – non disclosure viewed as the result of members not being aware as to what constituted a COI – The strategy NCC senior staff and chairs stated they used to deal with disclosure was one of repeatedly emphasising the policy at recruitment of members to the guideline and at each meeting and probing clinical members if they had “nothing to declare”: • you can only labour the point and hope they do declare because you do not know what they get up to. [Senior Staff NCC, I1] Results (5): Managing COI • Handling conflicts of interest at recruitment of committee members – policy restricted the pool of well qualified candidates for GDG positions – a particular issue for chair appointments • we do not shortlist people [for chair] we think will be conflicted – it leaves you in a difficult position as they are often leaders in the field ... the people who know the most about it have the most conflicts [Senior Staff NCC, I5] – could be mitigated if the individual agreed to be appointed as a group member Results (6): Managing COI • Handling conflicts of interest at committee meetings – chairs and NCC senior staff emphasised that it was important to manage the group process carefully and required good chairing skills – Need to be clear with members about what COI categories were “problematic” and chair the meeting in such a way to facilitate openness between members: • Making it clear what evidence is going to be discussed and creating an environment where people can be open [Senior Staff NCC, I2] Results (7):Managing COI • Handling conflicts of interest at committee meetings – requirement to exclude members from the meeting was a disruptive event: • a source of stress for both chairs and members • had adverse effects on the task of each meeting • seen as a particular problem with clinical guideline development, where the clinical pathway for a condition and attendant multiple interventions are being considered: – In guideline development things are linked ... someone could have a conflict for different bits of the chain ... but you are discussing a whole pathway – people having to leave the room – can be very disruptive. [Senior Staff NCC, I4] – impact of this disruption can be minimised with good group chairing skills Discussion • Key Findings – Application of the NICE policy – specifically identifying and managing COI in clinical guideline development - was not straightforward • Strengths and weaknesses of study – Appropriate design – Need ethnographic observation of meetings Discussion • Related Research – consistent with a qualitative study exploring how research ethics committees identify and manage COI – We offered new insights into “exclusion” of members (type of committee important) Klitzman R. "Members of the same club": challenges and decisions faced by US IRBs in identifying and managing conflicts of interest. PLoS One 2011;6(7):e22796. Conclusions • Key recommendations – national guideline developers • it is necessary but not sufficient for there to exist an explicit and detailed COI policy • implementation of a guideline COI policy often requires difficult and complex judgements to be made by senior clinicians and managers • appropriate training of chairs and members should be provided to equip them with the knowledge and skills to manage reporting of COI Conclusions • Questions for debate – Should we focus only on financial COI? • Are all COI equal? Are they a COI at all?? – Bero L. What is in a name? Nonfinancial influences on the outcomes of systematic reviews and guidelines Journal of clinical epidemiology 2014; 67:1239-41. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.015 – Which settings should we consider? – If clinicians are inherently conflicted should we give methodologists the lead role in guideline development? – Guyatt G, Akl EA, Hirsh J, Kearon C, Crowther M, Gutterman D, Lewis SZ, Nathanson I, Jaeschke R, Schunemann H. The vexing problem of guidelines and conflict of interest: a potential solution. Ann Intern Med 2010 June 1;152(11):738-41. – Wither self regulation? • Does NZ need a sunshine act? Thank you! tim.stokes@otago.ac.nz Acknowledgements • Study was unfunded – Carried out as part of an audit of NICE’s COI policy – Work was initiated while TS was a salaried employee of NICE (Consultant Clinical Adviser)