Fall 2009

advertisement

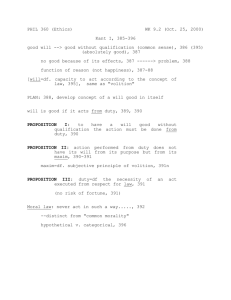

1 Corporations Professor Bradford Fall 2009 Exam Answer Outline The following answer outlines are not intended to be model answers, nor are they intended to include every issue students discussed. They merely attempt to identify the major issues in each question and some of the problems or questions arising under each issue. They should provide a pretty good idea of the kinds of things I was looking for. If you have any questions about the exam or your performance on the exam, feel free to contact me to talk about it. I graded each question separately. Those grades appear on your printed exam. To determine your overall average, each question was then weighted in accordance with the time allocated to that question. The following distribution will give you some idea how you did in comparison to the rest of the class: Question 1A: Range 2-8; Average = 5.73 Question 1B: Range 0-8; Average = 4.83 Question 2: Range 0-9; Average = 7.08 Question 3: Range 3-9; Average = 6.03 Question 4: Range 0-8; Average = 2.63 Question 5: Range 0-9; Average = 6.33 Question 6: Range 0-9; Average = 5.24 Question 7: Range 0-9; Average = 5.13 Total (of unadjusted exam scores, not final grades): Range 2.79-7.69; Average = 5.38 2 Question 1 Part A Duty of Care Directors have a duty to inform themselves before making a decision. Van Gorkom. Betty and Carla could have violated that duty by failing to read the report on the transaction, which would have disclosed the conflict of interest. However, the standard is gross negligence, Van Gorkom, and since they were extensively informed by the briefing at the meeting, that might have satisfied the duty. In any event, the certificate of incorporation disclaims liability to the full extent allowed by law, and that would include liability for breach of the duty of care. See Del. § 102(b)(7). Duty of Loyalty Anne has a conflict of interest with respect to the transaction because her husband, Hub, has a financial interest in it. As a result of his ownership of 5% of Buyer’s stock, Hub would profit if Buyer profits. Anne would not be liable if she could show the transaction was fair to the corporation. Fairness involves two elements, fair price and fair dealing. Weinberger; HMG/Courtland Properties v. Gray. Anne’s lack of involvement in the sale supports a claim of fair dealing; however, the deal was negotiated by two corporate employees that she as CEO might control. Fair dealing does not appear to be at issue here. Anne was not involved in the sale in any way; as far as the facts indicate, the process was fair. Fair price is more difficult. The report, if accurate, would tend to support fairness, because it indicates why the sale is a good deal for the corporation. However, the burden of proof is on Anne, HMG/Courtland Properties, and more details are needed. An alternative is to argue that approval by Betty and Carla, who clearly are disinterested directors, removed the conflict of interest taint, and any liability on Anne’s part. Del. § 144(a)(1) provides for approval by disinterested directors if “the material facts as to the director’s or officer’s relationship or interest and as to the contract or transaction are disclosed or are known to” the directors. Section 144(a) does not literally apply because its opening clause does not cover a transaction where a director’s spouse has an interest in the other party to the transaction, only one where the director has a financial interest. However, even if section 144 does not literally apply, the Delaware Supreme Court has made it clear that approval by disinterested directors removes a potential conflict even outside the context of section 144. See Broz. The information about the conflict of interest is disclosed in the report provided to the directors, but neither Betty nor Carla read the report, so neither knew about the conflict at the time of their vote. Although 144(a)(1) literally says disclosure is enough, it makes little sense to give this vote full cleansing effect if the disinterested directors 3 didn’t even realize there was a conflict. Thus, it’s unclear that the vote will be effective. If not, Anne wins only if she can show the transaction was fair to the corporation at the time it was approved. Part B If Seller were a limited partner, the result could be different. The general partners in a limited partnership owe the same duties and are subject to the same liabilities to the partnership and other partners as the partners in a general partnership. RULPA § 403(a); 403(b), second sentence. These duties include a duty of care, RUPA § 404(c) and a duty of loyalty, RUPA § 404(b). The partners’ failure to read the report could violate the duty of care. The standard of care for partners is gross negligence, but that’s the same standard applied by Van Gorkom, so the analysis doesn’t change. The analysis of the duty of loyalty is also basically the same. RUPA § 404(b)(1) clearly covers self-dealing behavior—this could be a profit derived from the conduct of the partnership business. Alternatively, Anne is dealing with the partnership as someone with an adverse interest. RUPA § 404(b)(2). However one categorizes it, it’s clear that self-dealing is a breach of fiduciary duty in the partnership context. As in the corporate setting, approval by disinterested partners would probably cleanse the conflict of interest. RUPA § 103(b)(3)(ii) indicates that, although the duty of loyalty may not be eliminated, all of the partners may authorize a transaction that would otherwise violate the duty of loyalty. Transplanted into the limited partnership setting, would this require approval by all partners, including the limited partners? If so, that has not occurred; only the general partners approved the transaction. In addition, such authorization must occur “after full disclosure of all material facts.” The same disclosure issue arises as in the corporate setting. The effect of the provision eliminating duties is also unclear. RUPA § 103(b)(4) does not allow for elimination of the duty of care. It provides that the partnership agreement may not “unreasonably reduce” that duty. It’s therefore not clear what “to the full extent allowed by law” would mean in this context. Absent a clearer specification, the duty of care arguably survives. However, it is unclear that RULPA sec. 403(a) means to incorporate section 103(b). It indicates that partners shall have the duties specified in the RUPA, “except as provided in . . . the partnership agreement,” with no limitation on what the partnership agreement may provide. Read literally, this would allow full elimination of fiduciary duties, without any cross-reference to what RUPA § 103(b) allows. It’s doubtful that this is what the drafters intended, but, if read this way, Anne, Betty, and Carla would have no liability, either for breach of the duty of care or for breach of the duty of loyalty. 4 Question 2 A dividend preference is an amount the corporation must pay to a particular class of stock before dividends are paid to other shareholders. In this case, the $1 preference means that the Class A shareholders are entitled to receive $1 per share before any other shareholder receives a dividend. This preference is cumulative, meaning that, if dividends are not paid in any given year, the amount of the preference carries over to the following year and increases the preferential amount that must be paid in the following year. For instance, if no dividends are paid in 2009, then $2 must be paid in 2010 before other shareholders receive a dividend, and if no dividends are paid again in 2009 or 2010, then the preferential amount in 2011 is $3. This preference is also fully participating, which means that the Class A shareholders not only receive their preferential amount, but after their $1 preference is paid, they also get to share equally (on a per-share basis) in the dividends paid to all shareholders. Class A shareholders are not just limited to their preferential amount. 5 Question 3 The issue is whether Watson had sufficient authority to bind Pelini and his sole proprietorship, Husker Sales. As an employee of Husker Sales (and its owner Pelini), Watson is an agent. The principal, Pelini, can be bound on a contractual transaction conducted by the agent, Watson, based on (1) actual authority; (2) apparent authority; or (3) inherent authority. Restatement Second of Agency (RSA) § 140. Inherent Authority Watson does not appear to have inherent authority. The RSA definition of inherent authority, RSA § 8A, is not very informative, but the basic idea is authority that is inherent in the agent’s particular job. Here, Watson was Pelini’s personal secretary. The authority to order $25,000 of electronics for the company is not inherent in the position of secretary. Thus, Pelini will not be liable on the basis of inherent authority. Actual Authority Actual authority is based on words or other conduct of the principal that causes the agent to believe that the principal desires him to do what he did. RSA § 26. The question is whether the agent’s actions were “in accordance with the principal’s manifestation of consent to him.” RSA § 7. Watson was unaware of Pelini’s conversation with Suh, so actual authority cannot be established on the basis of that conversation, only on the basis of the conversation between Pelini and Watson. Pelini told Watson that he wanted Watson to buy electronic equipment so the sales people could stop recording information on paper. This could include tablet computers, and “nothing fancy” is probably too indefinite to limit that grant of authority to exclude tablet computers. However, Pelini also handed Watson a brochure for PDAs and indicated that they would “do the job.” The question is whether this was intended to be, and understood to be, a limitation on the broader conversation—in other words, to limit Watson to PDAs or at least to something with a similar price—or just an illustration of one possibility. The question is whether Watson should have reasonably understood from the brochure, the “nothing fancy” statement, and the statement that “something like this” would do the job, that a $1000 computer was beyond the intended grant of authority. Watson signed the contract in the name of Husker Sales, so there is no question that Husker Sales was a disclosed principal. RSA § 4(1). If a court decides that tablet computers were within what Watson reasonably understood from the conversation, then Watson had actual authority, and Pelini, the principal, is bound to the contract in the name of Husker Sales. RSA § 144. If not, then Pelini is bound only if Watson had apparent authority. 6 Apparent Authority Apparent authority is based on communications or actions by the principal that lead the third party to believe that the agent had authority. RSA § 8. The question is whether written or spoken words of the principal, reasonably interpreted, would lead the third party to believe the agent had the authority to enter into the transaction. RSA § 27. Pelini did not communicate directly with Gates, but Gates did know about the Pelini-Suh conversation. Pelini told Suh “ I think I will have Watson buy tablet computers for everyone.” Based on that conversation, Gates could reasonably assume when Watson entered his shop that Watson was authorized to buy the tablet computers on behalf of Pelini. RSA § 27 does not require a communication directly to the third person, although RSA § 8, which speaks of “the other’s manifestations to such third persons,” arguably does. If an indirect manifestation through Suh is sufficient, Watson had apparent authority to buy the computers, and Pelini would be liable under RSA § 159. If an indirect manifestation through Suh is insufficient, Watson would not have apparent authority. 7 Question 4 [NOTE: Many of you missed the entire point of this question. The question says simply that Sandy plans to propose the resolution for a shareholder vote at the annual meeting and asks about any legal problems with that resolution. The question doesn’t say that Sandy wishes to include her proposal in management’s proxy solicitation or even that Sandy plans to solicit proxies herself. Many of you incorrectly assumed that Sandy could present this resolution to the shareholders only if it fits within Rule 14a-8.] Sandy does not have the legal power to do what she proposes to do. Del. § 141(a) indicates that the business and affairs of the corporation shall be managed by or under the direction of the board of directors, except as otherwise provided in the statute or in the corporation’s certificate of incorporation. Sandy’s proposed resolution clearly limits the management discretion of the board by specifying a particular recycling requirement. Under § 141(a), a provision in Library’s certificate of incorporation that required this could be valid, because § 141(a) allows the management authority of the board to be restricted in the certificate. However, Sandy and the shareholder lack authority to initiate amendments to the certificate of incorporation. Del. § 242(b)(1) says amendments to the certificate must first be adopted by the board of directors. Sandy and the shareholders do have the power to initiate amendments to the bylaws. Del. § 109(a). However, § 141(a) does not allow for restriction of the powers of the board through the bylaws, only through the certificate of incorporation. The Delaware Supreme Court recently made it clear that the bylaws may not be used to mandate how the board should decide specific substantive business decisions. CA, Inc. v. AFSCME Employees Pension Plan. Thus, although Sandy has the authority to amend the bylaws, a bylaw amendment can’t do what she wants to do. At best, Sandy and the shareholders could adopt a resolution recommending that the board follow the proposed policy, but the shareholders cannot force the directors to abide by this suggestion. 8 Question 5 This action is invalid and Stooge Partnership may not pay Moe and Larry the $500 per year compensation. RUPA § 401(h) provides that a partner is not normally entitled to remuneration for services performed for the partnership. This would exclude compensation for Moe’s and Larry’s management of the partnership. The only statutory exception is for services winding up the business, which is not what’s happening here. The partnership agreement may modify this default rule, RUPA § 103(a), since it’s not one of the provisions specifically mentioned in RUPA § 103(b). However, Stooge doesn’t have a partnership agreement, so the rule in § 401(h) has not been contractually modified. Section 401(j) provides for majority rule with respect to decisions in the ordinary course of business, but that cannot override the statutory prohibition on salaries in section 401(h). That would require an amendment to the partnership agreement (or, in this case adoption of a partnership agreement after the fact), which requires unanimous consent. RUPA § 401(j). Therefore, in spite of the majority vote, the compensation is invalid under § 401(h). 9 Question 6 Do the Proxy Rules Apply? Trek Corporation is required to register its stock pursuant to section 12 of the 1934 Act because its stock is traded on the New York Stock Exchange. Exchange Act § 12(a). Therefore, Trek is subject to the SEC’s proxy rules. Exchange Act § 14(a) (“in respect of any security . . . registered pursuant to section 12 of this title”). Is Kirk’s Letter a Solicitation? The proxy rules only cover proxy solicitations, as defined in Rule 14a-2(l). If the letter is not a “solicitation,” it cannot violate any of the proxy rules. Kirk’s March 1 letter does not ask anyone for a proxy or to execute a proxy, so it’s not covered by the definition of solicitation in Rule 14a-1(l)(1)(i) or (ii). The letter does not include a form of proxy, so it doesn’t fit within the first part of Rule 14a1(l)(1)(iii). Therefore, it is a “solicitation” and potentially subject to the proxy rules only if it is “reasonably calculated to result in the procurement, withholding, or revocation of a proxy.” Rule 14a-1(1)(iii). It probably is. The letter discusses Trek’s performance and argues that Trek shareholders deserve more. It is highly likely that it could affect the willingness of the Trek shareholders who receive it to give their proxies to management to reelect the incumbent directors. Even though the letter falls within the base definition, it would still not be a solicitation if it is excluded from the definition by Rule 14a-1(l)(2). Subsection (i) doesn’t apply because the letter is not in response to an unsolicited request from a security holder. Subsection (ii) doesn’t apply because this letter doesn’t relate to anything under rule 14a-7. Subsection (iii) doesn’t apply because neither Kirk nor Spock are merely performing ministerial acts in connection with the letter. And subsection (iv) doesn’t apply because, even if the letter arguably merely states how Kirk intends to vote and why, it (A) isn’t by means of any of the publications identified in (A); (B) isn’t directed to people whom Kirk owes a fiduciary duty; and (C) is not in response to unsolicited requests. In addition, Kirk is otherwise engaged in a proxy solicitation. Is Kirk’s Delivery of the Letter Exempted? Even though the letter is a solicitation, Kirk’s delivery of the letter to the six shareholders is exempted from most of the proxy rules by Rule 14a-2(b)(2) because the total number of persons solicited is less than ten. It eventually makes its way to more than ten people, but Kirk can’t be charged with that because he did not approve the subsequent recirculation of the letter and was not even aware that Spock was doing that. Kirk can use Rule 14a-2(b)(2) even though he eventually engages in a full-blown proxy solicitation because (b)(2)’s use is not limited to those who do not otherwise engage in a proxy solicitation. Therefore, it appears that Kirk’s original circulation of the letter is not 10 a violation of the proxy rules. Note, however, that Rule 14a-9, the antifraud rule, would apply to this communication even though it’s exempted from most of the other rules. See the opening sentence of 14a-2(b). Is Spock’s Recirculation of the Letter a Violation? The second issue is whether Spock’s recirculation of the letter violates the proxy rules. The letter is still a solicitation, for the reasons given earlier. Spock clearly can’t use Rule 14a-2(b)(2) because he sent the letter to more than ten people. Thus, Spock violates the proxy rules unless the letter fits within Rule 14a-2(b)(1). Rule 14a-2(b)(1) exempts from most of the proxy rules (but not the antifraud rule) any communication, as long as the person making the communication “does not . . . seek directly or indirectly, either on [his] . . . own or another’s behalf . . .” the power to act as proxy. Spock is not asking anyone for a proxy and is not otherwise involved in a proxy solicitation. Kirk clearly is involved in a proxy solicitation; the issue is whether Spock is acting indirectly on Kirk’s behalf. That seems unlikely. Spock was unaware that Kirk was going to engage in a proxy solicitation until after Spock resent Kirk’s letter and Spock was not involved in Kirk’s solicitation in any way. Therefore, even though the letter was written by Kirk, who is involved in a proxy solicitation, Spock’s recirculation of the letter probably falls within the Rule 14a-2(b)(1) exemption. 11 Question 7 For trading on nonpublic information to violate Rule 10b-5, the use of the information must breach a fiduciary duty. Chiarella. Neither Anna nor Fred has an employment or other relationship directly with Magna, the source of the information, so this is not classical insider trading of the type found illegal in Texas Gulf Sulphur. Anna’s Potential Liability Under Dirks A tippee provided information by a corporate insider can be liable if the insider breached her fiduciary duty in providing the information and the tippee knew or should have known of the breach of duty. Dirks. Anna received the information about the corporate development from Paula, an insider of Magna, who does owe a fiduciary duty to Magna. However, Paula did not breach her fiduciary duty in providing the information. To be a breach of duty within the meaning of Dirks, the insider must be providing the information for personal gain. Paula is releasing the information as part of her responsibilities for Magna, not to get a personal gain. In fact, Paula specifically requested that the analysts keep the information confidential. Thus, Anna has no liability under Dirks. Anna’s Potential Liability Under O’Hagan Anna may also be liable if she breaches a duty of confidentiality owed to the source of the information, in this case Magna. O’Hagan. Such a breach of duty can be based on an agreement to maintain information in confidence. Rule 10b5-2(b)(1). Here, Paula asked the analysts to keep the information confidential, but Anna never assented to that request, so there doesn’t appear to be an agreement, unless one can construe not hanging up as agreement. Alternatively, even if Anna did not agree to keep the information confidential, Anna may have a duty based on “a history, pattern, or practice of sharing confidences,” such that both Anna and Paula knew that Anna was expected to keep the information confidential. Rule 10b5-2(b)(2). More facts would be needed to establish such a duty. If there were a duty of confidentiality, then Anna’s release of the information to Fred, knowing that he intended to trade on it, would cause her to violate Rule 10b-5. Fred’s Liability Fred’s liability, if any, would have to be derivative of Anna’s, as he has no history of confidentiality and he did not agree to keep the information confidential. Fred clearly does not breach any duty to Anna; she expects him to use the information. Nor does Fred owe any duty directly to Magna. Therefore, Fred’s only potential liability is as a tipee under Dirks. If Anna breached her duty under the O’Hagan doctrine, then Fred could be liable under Dirks. Anna clearly breached her duty for personal gain, the $500 payment from 12 Fred. Therefore, Fred could be liable if he knew or should have known that Anna was breaching her duty. The hard issue is whether Fred should have known that Anna had a duty of confidentiality, since that duty is dependent on an agreement by Anna or a history of past confidentiality. Should Fred have known of that, since, absent an agreement, Anna’s provision of the information would not be in breach of duty. It’s not enough that Fred know the source of the information or that it’s nonpublic; he must know that Anna breached a duty in providing it to him. If he knew or should have known that, then Fred would be liable—but, again, only if we can establish that Anna herself breached a duty.