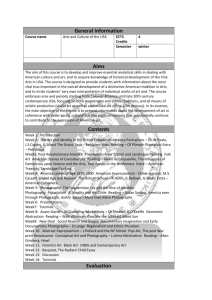

Week 3 Lecture 2 Reporting Trauma

advertisement

Katy Parry, A Visual Framing Analysis of British Press Photography During the 2006 Israel –Lebanon conflict 2010 3: 67 Media, War & Conflict Branston G and Stafford R — The Media Students’ Book, 3rd Edition (Routledge 2006) Read pages 134-146 from Chapter 5 titled ‘Ideologies and Power’ Read case study: Selecting and Constructing News ANSWER THE FOLLOWING QUESTIONS 1, Do you think a news report can ever be balanced? Why or why not? How can a journalist make sure to tell a story fairly? (300 words) 1. Should journalists show emotion in their news reports? Why or why not? (300 words) 2. Find an example of a TV journalist or print journalist discussing a story in an emotional way. Be prepared to share the example in class. Images, Compassion and Reporting Trauma Adapted from Two Lectures Given by Dr. Gareth Bentley in November 2011. Introduction • ‘….pictures…… are more imperative than writing, they impose meaning at one stroke, without analysing or diluting it.’ (Barthes, 1972) • Scopophilia or scoptophilia, from Greek "love of looking", is deriving pleasure from looking. From Bentley, November 2011 • ‘By ideological elaboration we mean the insertion of the photo into a set of thematic interpretations which permits the sign (photo), via its connoted meanings, to serve as the index of an ideological theme. • Ideological news values provide a second level of signification of an ideological type to an image which already (at the denotative level) signifies. From Bentley, November 2011 Barthes – Two Aspects of an Image Denotation • The object itself photographed. Most readers or viewers will agree on the denoted object (e.g. here is a little boy who is a soldier). Connotation • Linking the object with other signs and meanings. Connotation may vary depending on who is doing the looking (or reading). Susan Sontag – Photography and Ethics • In her Essay On Photography Sontag says that the evolution of modern technology has changed the viewer in three key ways. She calls this the emergence of a new visual code. • . “In teaching us a new visual code, photographs alter and enlarge our notion of what is worth looking at and what we have the right to observe” . This is what Sontag calls a change in “viewing ethics” . • To Sontag, photographs “now provide most of the knowledge people have about the look of the past and the reach of the present”(4). Without photography only those few people who had been there would know what the Egyptian pyramids or the Parthenon look like, yet most of us have a good idea of the appearance of these places. Photography teaches us about those parts of the world that are beyond our touch in ways that literature can not. From Bentley, November 2011 Sontag (2) • • • Sontag also talked about the way in which photography desensitizes its audience. She describes viewing images of the Holocaust“When I looked at those photographs something broke... something went dead, something is still crying” Sontag examines the relationship between photography and reality. Photographs are depicted as a representation of realism. Sontag claimed that “such images are indeed able to usurp reality because first of all a photograph is not only an image, an interpretation of the real; it is also a trace, something directly stencliled off the real (Sontag, Susan (1982), The Image World ) Sontag observed some uses of photography, “Photography has become one of the principal devices for experiencing something, for giving an appearance of participation” (Sontag,1977), such as memorizing and providing evidence. She also states that “to collect photography is to collect the world.” (Sontag,1997) From Bentley, November 2011 Memento Mori • Sontag believes that photography implies that we know about the world if we accept it as the camera records it. She states that photography has ‘become one of the principal devices for experiencing something, for giving an appearance of participation’.] • She refers to photographs as memento mori, where to take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability and mutability. The rise of the ‘iconic’ image ‘Moments of visual eloquence’ that ‘acquire exceptional importance in public life and are believed to ‘motivate public action on behalf of democratic values’. (Hariman and Lucaites, 2003:38) •Recognised by everyone within a public culture •Representations of historically significant events •Images acquire iconic status, reducing complex and controversial news items into a memorable visual statement. •The iconic image may be reused/abused in new contexts, across media No caption needed? “All photographs wait to be explained or falsified by their captions.” (Sontag, 2003) Soldiers smuggle grenades in a basket covered with water hyacinth, Bangladesh, 1971 (Mohammed Shafi) Paris streetdancer, 2007 (Denis Darzacq) Images and War Reporting Media images of war • Photographic images of war have been used to accentuate and lend authority to war reporting since the early 20th century, with depictions in 1930s picture magazines of the Spanish Civil War • The period between the world wars was a time when modernist notions of news surveillance and photographic objectivity were becoming institutionalized in the norms and conventions of professional media practice, first in the European picture magazines of the 1920s and 30s (and later Life and Look in the US), and then in the daily press throughout most of the industrialized world between 1930 and 1950. • By the 1960s Vietnam War coverage came to be associated with personal, independent and uncensored reporting and image making • This new style of journalism arguably shattered the propagandist idealized mythical narrative of the Vietnam War • From the 1930s to the rise of television infotainment and the 24/7 news cycle, war photography trafficked in emotional content through ‘dramatic visual impact’ From Bentley, November 2011 Objectivity • • • • • • • The emphasis on war photography’s emotional impact is closely tied to a presumption of photography’s verisimilitude and objectivity It conveys an immediate, direct authentic sense of real events to the viewer, more emotional and less intellectual We therefore tend to treat images as primarily the products of individual photographers We want to be the recipients of an emotional and experiential transfer that goes beyond a simple ‘recording’ of the event to provide us with a human connection to the courage, determination, pain, or suffering of the picture’s actors Since the Spanish Civil War, theatres of conflict have been seen as a proving ground for photojournalists, and war photographers have been celebrated as the daring and heroic figures of a particular scopic regime; a regime which utilized the technology of modern media to bring apparently authentic views of distant events. News photos have a specific way of passing themselves off a aspects of ‘nature’ The ‘ideology of objectivity’ (Hall, 1973) derives from one of the most profound myths in the liberal ideology: the absolute distinction between fact and value, the distinction that appears as a common-sense ‘rule’ in newspaper practice as ‘the distinction between facts and interpretation’: the empiricist illusion, the utopia of naturalism From Bentley, November 2011 Brothers (1997) ‘In war photography…. Responses are magnified. Danger hovers at the edged of all such images; the passions they record are always the most extreme. The possibility of dying that is their subtext, for their subjects as much as the photographer, means they make urgent claims on our attention, allowing us both to feel a sense of our own mortality and to hold that sense at bay. The forcefulness of their messages makes them unlike any other genre of image, the power of desire to communicate impelling them towards representations that touch us more deeply and more directly.’ (xi) Distance • Images offer viscerally exciting and voyeuristic glimpses into theaters of violence that, for most viewers are alien to everyday experience (Taylor, 1998) • ‘….war and photography now seem inseparable, and plane crashes and other horrific accidents always attract people with cameras. A society which makes it normative to aspire to never experience privation, failure, misery, pain, dread disease, and in which death itself is regarded not as natural and inevitable but as a cruel, unmerited disaster, creates a tremendous curiosity about these events- a curiosity that is partly satisfied through picture taking.’ (Sontag, 1997: 167) Images of war seduce us into thinking that we can experience human events vicariously, at home in our living rooms, through cable, satellite or internet We should not confuse news and documentary images with those of entertainment fiction, no matter how much commercial media encourages us to do so This requires that we study the production and use of these images at multiple levels, and stand back from our tendency to ‘witness’ them as the shared experiences of our photographer proxies We must remain conscious of the fact that contemporary news operations, driven as they are by marketing concerns, routinely exploit fear, voyeurism and emotional fascination to boost ratings and circulation. • • • • Bentley, November 2011 Pulitzer prize-winning David Turnley, World Press Photo of the Year, 1991 • The photo is comparable to Vietnam photos in its human expression of trauma • It stands in stark contrast to the great body of techno-war Gulf War images Bentley, November 2011 Conclusion • It was not surprising , in the early days of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, to hear a CBS news reader on 48 Hours claim: ‘the search is on for the one great image that will define the battle of Iraq’ (‘Defining the War’, 48 Hours, CBS, 1 april 2003; quoted in Hariman and Lucaites, 2007: 291 • Back to the toppling statue thing – they tried to make that the iconic image! • To understand why we get a steady diet of war images, why many other types of revealing and informative images remain unseen, we need to view war photographs not as reflections of the events and experiences photographers encounter in war zones, but as the results of a continuing practice of cultural production that is also a tool of government management, media business and political persuasion From Bentley, November 2011 Reporting Trauma Ethiopia 1984 • Going back to our discussion on objectivity,BBC has run stories where the journalist’s emotional reaction was part of the story. • Images play a central role Michael Burke’s report in Ethiopia, 1984 (very graphic images) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XYOj_6OY uJc&feature=related • This reporting led to Live Aid. Trauma • Why show these images? Is it about empathy? • Live Aid happening was a real thing, a good thing – but is Sontag right that its not ethical to watch this level of suffering? • According to Meek (2010), trauma also sheds light on ethical issues. He stresses the analysis of unconscious structures of political identities rather than identification with, or empathy for, the victim/survivor of trauma. The latter discourse of identification/empathy is argued by him to be problematic because it “may participate in structures of power and exclusion”, while regarding itself as progressive and liberal. Meek favours the former discourse because it reveals repressed violence to be the basis of both individual and group identity. (Terada, 2003: Benjamin, 1988). From Bentley, November 2011 Witnessing (1) • Another “practice of objectivity” from our last lecture. • Frosh and Pinchevski’s definition of media witnessing is as follows: ‘It refers simultaneously to the appearance of witnesses in media reports, the possibility of media themselves bearing witness, and the positioning of media audiences as witnesses to depicted events, configurations that are amenable to handy summary through a tripartite distinction …between witnesses in the media, witnessing by the media, and witnessing through the media’ (Frosh and Pinchevski (Eds., 2009), pp.1). From Bentley, November 2011 Witnessing (2) • Photography and video images of trauma make us “witnesses” as well. • Frosh (Frosh and Pinchevski, Eds.,2009, pp.69) takes the view that: ‘Media witnessing thus helps to maintain that unexciting but essential sphere of indifferent relations to strangers in which potential feelings of hostility are neutralized without requiring that individuals become personally acquainted or committed.’ From Bentley, November 2011 Civil inattention or objectivity? • Civil Innattention– psychology: in the same phyiscal space, you are aware of others but not acting in any particular way towards them. • For example, in an elevator. • Do images of trauma and war promote the same thing? – We (the news viewer) are a ware of what is happening – but a THIN awareness. – In contrast to the THICK awareness of our own lives and problems.