- National Centre for Vocational Education Research

advertisement

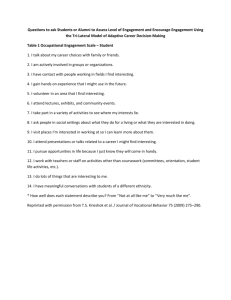

The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations Gavin Moodie RMIT University NATIONAL VOCATIONAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING RESEARCH PROGRAM WORKING PAPER The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author/ project team and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government, state and territory governments or NCVER. Any interpretation of data is the responsibility of the author/project team. Publisher’s note Additional information relating to this research is available in The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations: support document. It can be accessed from NCVER’s website <http://www.ncver.edu.au/publications/2537.html>. © Commonwealth of Australia, 2012 With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, the Department’s logo, any material protected by a trade mark and where otherwise noted all material presented in this document is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au> licence. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website (accessible using the links provided) as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/legalcode>. The Creative Commons licence conditions do not apply to all logos, graphic design, artwork and photographs. Requests and enquiries concerning other reproduction and rights should be directed to the National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER). This document should be attributed as Moodie, G 2012, The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations, NCVER, Adelaide. ISBN 978 1 922056 33 7 TD/TNC 109.20 Published by NCVER, ABN 87 007 967 311 Level 11, 33 King William Street, Adelaide SA 5000 PO Box 8288 Station Arcade, Adelaide SA 5000, Australia P +61 8 8230 8400 F +61 8 8212 3436 E ncver@ncver.edu.au W <http://www.ncver.edu.au> About the research The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations Gavin Moodie, RMIT University This research explores how the connections between qualifications and work can be improved to help strengthen educational pathways and occupational outcomes. This working paper is an initial examination of what is known about pathways in tertiary education as well as the loose associations between vocational qualifications and the jobs graduates do. The next stage of the research will explore these pathways in more detail through interviews with tertiary students, graduates, teaching staff and managers. This paper is part of a wider three-year program of research, ‘Vocations: the link between postcompulsory education and the labour market’, which is investigating both the educational and occupational paths that people take and how their study relates to their work. This particular paper looks at these pathways within and between VET and higher education. Moodie is also interested in the link between educational qualifications and work. He notes that these are not as strong as might be expected in a vocationally oriented tertiary education system like Australia’s. The next part of the research will therefore consider whether broader notions of occupation can deliver closer matches between skills and occupations. Tom Karmel Managing Director, NCVER Contents Tables and figures 5 Introduction 6 Tertiary education pathways 8 The loose fit between vocational qualifications and work 14 Relating educational and occupational progression 19 Previous studies 19 Occupational and educational progression 23 Discussion 26 Conclusion 30 Acknowledgment 30 References 31 Support document details 33 NVETR Program funding 34 4 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations Tables and figures Tables 1 Basis of admission of domestic undergraduate students, 2008 2 Basis of admission of domestic bachelor students commencing 8 Australian higher education in 2008 10 3 Vocational students’ highest prior education level, 2009 12 4 Vocational students’ highest prior education level, by field of education, 2009 (%) 13 5 ANZSCO skill levels and corresponding education levels 15 6 VET graduates in 2007 who were employed 6 months after graduation showing the occupation for which they were trained, % employed in intended occupation and relevance of training to occupation not intended by training 7 Workers who left their job in 2001 and their skills match in 2002 and 2005 8 16 20 Net flows of workers into broad occupational groups by sex and age cohort, 1996—2001 22 Figures 1 Vocational education’s internal relations and relations with work 23 2 Higher education’s internal relations and relations with work 23 3 Nursing’s educational and occupational relations 24 4 Educational and occupational relations in some health fields 24 NCVER 5 Introduction Education serves three purposes: to develop students’ capacities to lead fulfilling lives, to contribute to desirable social ends such as developing students as citizens, and to contribute to desirable economic ends such as preparing students for work and a productive life. All levels and most types of education serve all three purposes, but with different emphases. Primary education mostly develops pupils’ capacities to lead fulfilling lives, but its development of pupils’ literacy and numeracy and its socialisation of pupils into groups begin their preparation as citizens and workers. Indeed, most Australian workers had only primary schooling until the middle of the twentieth century. Over the last two decades primary schooling’s balance of individual development and social and economic preparation has been broadly continued into secondary education in liberal market economies such as in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia. However, in Australia, the fast-expanding programs of vocational education in schools, including the Certificate of Applied Learning in Victoria, may be introducing a vocational track into upper secondary education. There are different arrangements in the coordinated market economies of Germany and other northern European countries, where the social partners of government, employers and unions more actively coordinate the supply of training and employment. There, upper secondary education tends to divide into two tracks. One track, followed by a minority of pupils in Germany, concentrates on academic and general development which prepares pupils for further education, typically in disciplinary knowledge. The other track, followed by a majority in Germany, concentrates either on prevocational education, which prepares pupils for subsequent specialised tertiary vocational education, or on vocational education, which prepares pupils for work upon completion of secondary education. Thus, much vocational education is at the secondary level in northern continental Europe and even in the US some upper secondary education is vocational — or career and technical education as it is called there. Tertiary education also develops students’ individual abilities, their capacities as citizens and their capacity for productive activity or work. Tertiary education serves these roles differently for different programs but also for different students. Students study the same program for different reasons. For example, some students in Australia undertake a certificate III in information technology to become an information technology support technician, some to understand and operate their home computer system independently and some to progress to a diploma and thence to a bachelor of information technology. Nonetheless, most Australian tertiary education has more emphasis on preparing students for work than primary and most secondary education, and this is the subject of the current project ‘Vocations: the link between post compulsory education and the labour market’, funded by the National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER). The project has three interrelated strands: Strand 1: entry to vocations — how to improve occupational and further study outcomes from entry-level vocational education and training (VET) including VET in Schools and certificates I and II Strand 2: the role of educational institutions in fostering vocations — how to improve occupational outcomes and educational pathways within vocational education and between vocational and higher education Strand 3: the nature of vocations today and their potential improvement — how to improve the development and use of skills in the primary industry, health, electrical/engineering and finance sectors and the relationship between qualifications and skills in these sectors. 6 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations This working paper raises issues relevant to Strand 2: the role of educational institutions in fostering vocations. It starts by outlining briefly what is known about pathways in tertiary education. It then describes the issue that stimulated this strand: the rather loose association between vocational qualifications completed by graduates and the jobs they do. The loose fit between qualifications and jobs isn’t necessarily a problem, but it seems inconsistent with the very vocational nature of Australian vocational education, which is based on work competencies. Most studies of education, qualifications and skills matches are static: they compare a person’s current education, qualification and/or skills with their current job. This is because there are only a few limited longitudinal studies that may support a dynamic analysis of the matching of a person’s education, qualification and skills to their career. Yet this seems to be important for people, employers, governments and society as a whole. A person’s current job may not be well matched with their education, qualification and/or skills but the match may improve with more experience or time in the labour market. Alternatively, a person’s education, qualification and skills may have been well matched with their employment for a long time but may be less well matched with their current job for a short period or as a staged wind-down to semi-retirement. This is discussed in the second part of the paper, which posits a framework for relating educational and occupational progression. The working paper concludes by anticipating the future direction of the strand’s research. NCVER 7 Tertiary education pathways Student transfer in tertiary education and, more generally, tertiary education pathways have been much studied in the United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom. The main sources of quantitative data on student transfers in Australia are considered extensively in a support document to this paper (available at <http://ncver.edu.au/publications/2537.html>). The main part of this paper presents the data available to inform the primary issue considered in the paper, the role of educational institutions in fostering vocations. Tertiary education gives students opportunities to progress or transfer from a program that prepares graduates for one occupation to a program that prepares them for a higher level in the same occupation, for another occupation or for a qualification of a lower level. In the language of student transfer studies, transfer may be upward, horizontal or reverse. Thus, a student may transfer from a diploma of nursing, which prepares them as an enrolled or division 2 nurse, to a bachelor of nursing, which prepares them as a registered or division 1 nurse. Alternatively, they may transfer to a diploma of business administration, which prepares them for the role of an office administrator, or to a certificate IV in health supervision, which prepares them for a role as a supervisor in an operational unit in a healthcare service. The data most commonly used to analyse tertiary education pathways are government aggregations of institutions’ statistical reports on their enrolments. The relevant data elements from the Australian Government’s higher education statistical collection are set out in the support document to this paper, which also describes some of its major limitations in coverage and quality. Because of these limitations Australian studies of student transfer from vocational to higher education rely most heavily on the basis for admission to the student’s current program. The basis for admission of domestic students to undergraduate programs in 2008, as reported by higher education institutions, is shown in table 1. Table 1 Basis of admission of domestic undergraduate students, 2008 Basis of admission % Completed or incomplete higher education program 23 Secondary education 45 Completed or incomplete VET award program 9 Mature-age special entry provisions 6 A professional qualification 1 Other basis 14 Not stated Total 2 100 Source: Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (2008). These data are not accurate for at least two reasons. First, because Australian universities’ admissions are dominated by the Australian tertiary entrance rank (TER), which is derived from secondary education, many students who have completed both secondary education and a vocational program are likely to be reported as being admitted on the basis of their secondary education. Secondly, institutions have inconsistent and not universally reliable ways of collecting these data: some collect them from students; some collect them from staff (although usually not the staff who decided the student’s admission); some derive them from students’ prior educational attainment; and 8 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations some report the coding of their state tertiary admissions centre. Nonetheless, with that caveat, it is worth examining these data in more detail. Table 2 shows the number of domestic students commencing an undergraduate program in 2008 for each field of education and the number and proportion admitted on the basis of a completed or incomplete vocational program. It will be noted, for example, that of the 922 students admitted to an undergraduate program in the mathematical sciences, only 16, or 1.7%, were admitted on the basis of a vocational program. Only 3.5% of students commencing an undergraduate program in the natural and physical sciences were admitted on the basis of vocational studies, much lower than the modest average of 9%. This is probably because the natural and physical sciences depend heavily on the sequential accumulation of disciplinary knowledge and skills, neither of which are developed extensively by Australian vocational education. The proportion of students admitted on the basis of a vocational education program is rather higher in information technology at 12%, which is expected. The proportions are very variable in engineering, probably due to a combination of variable student interest, preparation and university selection practices. The very high 43.2% reported for manufacturing engineering and technology is due to Victoria University admitting 18 of its 31 students in this field on the basis of a vocational program. The proportion of health students admitted on the basis of a vocational program is also very variable, but particularly noteworthy is the high 22.1% of nursing students admitted on the basis of a vocational program. Arguably, this should be higher because institutions reported that they admitted 3.5% of their nursing students on the basis of a professional qualification; many of these would be enrolled nurses with the equivalent of a certificate or diploma of nursing. The relatively high 13.2% of education students admitted on the basis of a vocational program may be vocational teachers seeking a higher educational qualification or qualification as a school teacher. The relatively high 11.6% of management and commerce students admitted on the basis of a vocational program is expected, as are the detailed fields with the highest proportions. Again, one would expect the high proportions of students admitted on the basis of vocational education in librarianship, information management and curatorial studies (36.8%), justice and law enforcement (24.1%), human welfare studies and services (14.9%) and sport and recreation (14.3%), and the low proportions in the liberal arts and social sciences. This is because these fields of education are more vocationally specific than the liberal arts and social sciences. NCVER 9 Table 2 Basis of admission of domestic bachelor students commencing Australian higher education in 2008 Basis of admission Total VET basis % VET basis Natural and physical sciences 5 301 131 2.5 Mathematical sciences 922 16 1.7 Physics and astronomy 196 7 3.6 Chemical sciences 321 12 3.7 Earth sciences 244 9 3.7 3 042 194 6.4 3.3 Biological sciences Other natural and physical sciences 9 050 297 18 898 664 3.5 531 59 11.1 Computer science 2 001 227 11.3 Information systems 1 561 239 15.3 Other information technology 1 832 186 10.2 Sub-total information technology 5 853 704 12.0 Engineering and related technologies 3 531 181 5.1 44 19 43.2 1 188 12 1.0 Sub-total natural and physical sciences Information technology Manufacturing engineering and technology Process and resources engineering Automotive engineering and technology 72 7 9.7 Mechanical and industrial engineering and technology 1 046 104 9.9 Civil engineering 1 522 76 5.0 Geomatic engineering 221 27 12.2 1 295 138 10.7 Aerospace engineering and technology 733 28 3.8 Maritime engineering and technology 167 0 0.0 5.6 Electrical and electronic engineering and technology Other engineering and related technologies 3 228 182 12 605 766 6.1 Architecture and urban environment 3 866 391 10.1 Building 1 546 210 13.6 Sub-total architecture and building 5 371 590 11.0 Agriculture, environmental and related studies 493 26 5.3 Agriculture 840 53 6.3 Horticulture and viticulture 189 21 11.1 Forestry studies 28 1 3.6 Fisheries studies 43 1 2.3 2 064 197 9.5 158 4 2.5 3 784 302 8.0 7.1 Sub-total engineering and related technologies Environmental studies Other agriculture, environmental and related studies Sub-total agriculture, environmental and related studies Health 238 17 3 348 18 0.5 11 835 2 619 22.1 1 311 1 0.1 Dental studies 676 37 5.5 Optical science 166 0 0.0 Veterinary studies 605 0 0.0 Public health 1 705 162 9.5 Radiography 736 14 1.9 Rehabilitation therapies 3 686 109 3.0 Complementary therapies 1 538 29 1.9 Medical studies Nursing Pharmacy Other health Sub-total health 10 6 332 476 7.5 31 852 3 466 10.9 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations Basis of admission Education Teacher education Curriculum and education studies Other education Sub-total education Total VET basis % VET basis 779 0 0.0 19 654 2 641 13.4 486 39 8.0 1 966 320 16.3 13.2 22 446 2 956 Management and commerce 6 725 506 7.5 Accounting 3 768 596 15.8 19 740 2 486 12.6 2 482 424 17.1 343 49 14.3 Business and management Sales and marketing Tourism Office studies 1 0 0.0 Banking, finance and related fields 1 413 138 9.8 Other management and commerce 4 638 293 6.3 Sub-total management and commerce 38 097 4 417 11.6 Society and culture 13 546 528 3.9 848 22 2.6 Studies in human society 6 872 518 7.5 Human welfare studies and services 5 594 831 14.9 Behavioural science 6 690 441 6.6 Law 8 239 196 2.4 Justice and law enforcement 2 997 723 24.1 163 60 36.8 Language and literature 1 790 56 3.1 Philosophy and religious studies 1 825 98 5.4 Economics and econometrics 2 272 54 2.4 566 81 14.3 Political science and policy studies Librarianship, information management and curatorial studies Sport and recreation Other society and culture 7 078 380 5.4 55 062 3 904 7.1 205 6 2.9 Performing arts 3 514 223 6.3 Visual arts and crafts 2 676 300 11.2 Graphic and design studies 2 601 350 13.5 Communication and media studies 9 240 486 5.3 Sub-total society and culture Creative arts Other creative arts Sub-total creative arts Food and hospitality Sub-total food, hospitality and personal services General education programs Other mixed field programs 2 418 77 3.2 20 507 1 434 7.0 58 4 6.9 58 4 6.9 6 660 18 0.3 124 0 0.0 Sub-total mixed field programs 6 784 18 0.3 Non-award 8 011 120 1.5 Sub-total non-award courses 8 011 120 1.5 206 939 18 540 9.0 Total Source: Special data request from the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, 6 August 2009. NCVER reports states and territories’ statistical collections on the previous highest education level of publicly funded vocational education students. The results for students enrolled in 2009 are shown in table 3. The figures are for all students — not just commencing students as reported for higher education above — and for students studying at all levels. It should also be noted that NCVER reports only previous qualifications completed, not those studied, as reported by higher education. It will be noted that 7.1% of vocational students have completed a bachelor degree or higher and NCVER 11 that 20.5% of students have a prior vocational education qualification — advanced diploma, diploma or certificate I to IV. Table 3 Vocational students’ highest prior education level, 2009 Previous highest education level Number % Bachelor degree/higher degree level 120 915 7.1 Advanced diploma/associate degree 24 038 1.4 Diploma 64 214 3.8 Certificate IV 69 068 4.0 Certificate III 156 948 9.2 Year 12 382 561 22.4 Year 11 171 372 10.0 Certificate II Year 10 Certificate I Miscellaneous education Year 9 or lower Did not go to school Not known Total 30 041 1.8 288 348 16.9 4 918 0.3 12 332 0.7 124 226 7.3 5 121 0.3 252 576 14.8 1 706 678 100.0 Source: NCVER National VET Provider Collection (2010, unpublished). These results are shown by field of education in table 4. It can be seen that 12.6% of publicly funded vocational education students in the natural and physical sciences hold a bachelor degree or higher. Some of these may be bachelor of science graduates gaining a laboratory skills qualification; similarly, the sizeable number of graduates studying vocational education in information technology may be graduates in the same field seeking practical skills. The available data on tertiary education pathways give some idea of the movement of students between educational levels by field of education. These show that most transfers are within tertiary education sectors, not between them. Thus, 23% of undergraduate higher education students were admitted on the basis of other higher education studies, while only 9% were admitted on the basis of vocational studies; 7.1% of vocational students’ highest prior qualification was a baccalaureate or higher, while 20.5% had another vocational qualification. The data also show that tertiary education transfers differ markedly by field of education. Unfortunately none of the data readily available reports the field of education of the source program, so it is not possible to calculate the extent of transfer between fields of education and whether these might vary by field of source or destination program. 12 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations Table 4 Vocational students’ highest prior education level, by field of education, 2009 (%) Previous highest education level Major program field of education Natural, physical sciences IT Eng. and related techs Archit. and building Ag., environ. Health Education Mgt and comm. Society and culture Creative arts Food, hosp., personal services Mixed field Bachelor degree/higher degree level 12.6 9.8 3.2 3.2 7.6 8.5 19.0 7.9 9.3 9.7 4.5 8.2 Advanced diploma/associate degree 1.5 1.7 1.0 0.8 1.4 2.0 3.0 1.6 1.5 1.8 1.1 1.3 Diploma 5.3 5.1 2.3 1.9 3.3 5.6 7.5 5.1 4.9 5.2 2.1 3.0 Certificate IV 7.8 8.0 2.8 2.5 3.6 8.5 6.3 5.5 5.1 6.9 1.8 2.2 Certificate III 11.6 10.3 11.1 8.7 10.3 13.2 8.9 9.2 13.9 6.9 5.5 5.5 Year 12 32.9 25.2 26.0 24.8 17.9 20.7 13.9 26.0 24.3 25.7 21.5 15.4 Year 11 6.4 8.3 11.9 12.9 9.8 7.5 4.8 10.0 8.3 9.8 14.5 6.5 Certificate II 1.0 2.5 1.8 1.5 2.8 1.4 0.7 1.8 1.7 1.5 2.2 2.0 10.1 12.9 20.9 22.6 19.1 12.0 8.3 15.4 14.2 15.6 22.4 15.0 Certificate I 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.3 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.9 Miscellaneous education 0.6 0.3 0.6 0.5 1.0 0.8 1.7 0.5 0.7 0.5 0.4 1.2 Year 9 or lower 2.8 3.8 6.0 6.5 9.0 3.9 6.5 5.2 4.8 5.1 6.9 18.2 Did not go to school 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.3 0.1 0.8 0.1 0.4 0.1 0.1 1.1 Not known 7.4 11.9 11.9 13.9 13.7 15.7 18.5 11.5 10.8 10.9 16.8 19.6 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 Year 10 Total Source: NCVER National VET Provider Collection (2010 unpublished). NCVER 13 The loose fit between vocational qualifications and work In Australia each VET program is related directly to a job or a work role. Its programs comprise units of competence specified in training packages: Units of Competency in Training Packages are developed by industry to meet the identified skill needs of industry. Each unit of competency identifies a discrete workplace requirement and includes the knowledge and skills that underpin competency as well as language, literacy and numeracy; and occupational health and safety requirements. The units of competency must be adhered to in assessment to ensure consistency of outcomes. (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations 2011a) Because of this, vocational education is often contrasted with higher education, which at least in principle educates students in disciplines which may be applied in different contexts and in different occupations. One would therefore expect that, while there may be a relatively loose fit between the field of education of higher education graduates in at least the liberal arts and sciences and the jobs they get, there is a reasonably close association between the field of education of vocational graduates and the jobs they occupy soon after graduation. However, this is not the case. Each training package is designed to prepare graduates for an occupation that is classified in the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) into one of eight major groups and into one of 43 sub-major groups. Thus, the certificate III in information technology is classified in the sub-major group 31 — engineering, ICT and science technicians — which is part of the major group 3, technicians and trades workers. Other sub-major groups in technicians and trades workers are: 32, automotive and engineering trades workers; 33, construction trades workers; 34, electrotechnology and telecommunications trades workers; 35, food trades workers, skilled animal and horticultural workers; and 39, other technicians and trades workers. A stratified, random sample of VET graduates is surveyed using the Student Outcomes Survey six months after completing their program, wherein they report on their outcomes, which include their occupation at the time of completing the survey. Karmel, Mlotkowski and Awodeyi (2008) compared the occupational classification of graduates’ training package with the classification of their occupation. They found, for example, that only 20.6% of graduates who completed an engineering, ICT (information and communications technology) or science technician training package were employed as an engineering, ICT or science technician six months after graduating in 2007 (Karmel, Mlotkowski & Awodeyi 2008, p.10). Some 29.9% of engineering, ICT or science technician graduates were employed as technicians and trades workers, which means that 9.3% were employed as technicians or trades workers in other fields. Only 47.8% of all vocational graduates in 2007 were employed in their relevant major occupational group and an even smaller 36.6% were employed in the sub-major group of their training package. (This rate has fallen in subsequent years.) However, there is considerable variation between occupations. Other training packages had matches at the major occupational group and sub-major group even lower than engineering, ICT or science technician graduates, the lowest being arts and 14 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations media professionals (22.2%, 7.5%1), specialist managers (14.6%, 8.3%) and hospitality, retail and service managers (12.6%, 10.5%). On the other hand, some training packages had very high matches: electrotechnology and telecommunications trades workers (92.1%, 85.7%), cleaners and laundry workers (88.8%, 84.8%) and construction trades workers (86.1%, 81.1%). Overall, 60.6% of technicians and trades workers worked in their own trade and 66.7% worked in some trade, giving 6.1% working in a trade other than the trade for which they were trained and 33.3% not working in any trade (Karmel, Mlotkowski & Awodeyi 2008, p.10). The Student Outcomes Survey asks students for their main reason for studying. Some 77.7% of graduates in 2007 said that their main reason for studying was related to employment. Of those, 51.1% were employed in their intended major occupation group and 39.7% were employed in their intended sub-major occupation group. The match for engineering, ICT or science technician graduates who studied for employment reasons increased to 32.5% in the major occupational group and 23.7% in the sub-major occupational group. However, the matching was much higher for the 25.4% of graduates who completed an apprenticeship or traineeship (70.8%, 60.7%) and higher still for graduates who completed an apprenticeship or traineeship in the technician and trade occupations (88.6%, 84.6%; Karmel, Mlotkowski & Awodeyi 2008, pp.12, 13). ANZSCO classifies each of its 43 sub-major occupational groups into 1 of the 5 levels shown in table 5. Table 5 ANZSCO skill levels and corresponding education levels Skill level Education level 1 Bachelor degree or higher 2 Associate degree, advanced diploma or diploma 3 Certificate IV or a certificate III and at least 2 years of on the job training 4 Certificate II or III 5 Certificate I or compulsory school education Source: Adapted from ABS (2005, p.13). Karmel, Mlotkowski and Awodeyi (2008, p.14) compare vocational graduates’ level of qualification with the skill level of their occupation to find that, of the 51.2% of graduates in 2007 who were not employed in their intended occupation of training, 25.5% were employed at the same skill level or higher and 16.0% were employed at a lower skill level, with the balance of 9.7% employed in occupations with an unknown skill level. The Down the Track Survey collects occupational data from vocational graduates aged from 15 to 24 years 30 months after their graduation. Karmel, Mlotkowski and Awodeyi (2008, p.15) report that, while the proportion of young graduates in the occupation for which they trained declines from 43.1% some six months after graduation to 40.5% some 30 months after graduation, the proportion of young graduates employed at a lower skill level also declines from 39.7% to 36.4%. They also found that the proportion of professionals and associate professionals in jobs for which they trained had increased appreciably by 30 months after graduation, from which Karmel, Mlotkowski and Awodeyi (2008, p.15) conclude that the matching process takes some time for the higher-skilled occupations. The Student Outcomes Survey asks graduates the extent to which their training was relevant to their current occupation. Karmel, Mlotkowski and Awodeyi (2008, p.19) report the proportion of graduates who said that their training was highly or somewhat relevant to their occupation even if it wasn’t the occupation for which they trained. Overall, 36.6% of graduates in 2007 were employed in the 1 Relative standard error > 25%. NCVER 15 occupation for which they had been trained and 41.2% said that their training was highly or somewhat relevant, even though they were employed in an occupation for which they had not been trained. So graduates’ training was directly or indirectly relevant to 77.8% of graduates. This was quite variable, ranging from 84.8% for technicians and trades workers to 73.2% of community and personal service workers reporting that their training was directly or indirectly relevant to their occupation six months after graduation. Conversely, 14.2% of technicians and trades workers reported that their training had little or no relevance to their occupation, in contrast to 25.6% of community and personal service workers (table 6). Table 6 VET graduates in 2007 who were employed 6 months after graduation showing the occupation for which they were trained, % employed in intended occupation and relevance of training to occupation not intended by training Intended occupation Employed in intended occupation Not employed in intended occupation Training has very little or no relevance % Occupation after training unknown % Training is highly or somewhat relevant % Training relevance unknown % % Managers 14.1 65.9 19.1 0.1* 0.8 Professionals 21.5 52.6 24.4 0.3** 1.2* Technicians and trades workers 60.6 24.2 14.2 0.1* 0.9 Community and personal service workers 43.8 29.4 25.6 0.2* 1.0 Clerical and administrative workers 23.0 53.7 22.3 0.1* 0.9 Sales workers 45.2 37.3 17.1 0.1** 0.3* Machinery operators and drivers 26.6 47.7 24.7 0.2* 0.7 Labourers 25.5 49.9 22.5 0.3* 1.9 Total 36.6 41.2 21.1 0.2 1.0 Notes: * Relative standard error greater than 25%; estimate should be used with caution. ** Fewer than 5 respondents in cell. Source: Karmel, Mlotkowski and Awodeyi (2008, p.19, table 9). Karmel, Mlotkowski and Awodeyi (2008, p.21) note that high proportions of graduates of some training packages report that their training was of little or no relevance to their occupation: these groups of graduates include arts and media professionals, 63.6% of whom report that their training was of little or no relevance to their occupation, sports and personal service workers (45.0%), ICT professionals (36.7%), road and rail drivers (35.3%), hospitality workers (34.0%) and engineering, ICT and science technicians (31.2%). Karmel and colleagues conclude: It appears that a narrow view of VET is appropriate only for a few courses. There are a number of trade courses (plus a couple of others) where it makes sense to design the course around a particular occupational setting. These courses would appear to fit very naturally into the world of training packages developed by industry skills councils. However, the majority of courses do not fit into this pattern, and the majority of graduates do not end up in the occupation which is the ‘intended’ occupation for the course. Most of VET is generic in this sense. This does not imply that the industry focus of VET is wrong, but it does imply that course designers need to be very wary of the range of contexts in which graduates are likely to use the skills they have acquired. It also implies that planners need to be very wary of trying to match training to particular occupations. This view is supported by the finding that the distribution of employment after completion of vocational training bears closer correspondence to the overall workforce distribution of 16 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations employment than it does to the intended areas of training. This, according to Cully et al. (2006), suggests that labour demand holds sway over supply and that the generic skills delivered through VET are valuable to employers. (Karmel, Mlotkowski & Awodeyi 2008, p.23) Karmel, Mlotkowski and Awodeyi’s work is an example of studies of the match between individuals’ years of education, qualifications and skills, and those required for their current job. There are now extensive studies of education, qualifications and skills mismatches for all levels of the workforce in many Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, where a variety of methods have been used.2 About 30% of Australian workers have education, qualifications or skills that are not well matched to their job. This is because, variously, some workers are in jobs that don’t need their level of education (education underuse), some are in jobs which normally require a higher level or longer education (undereducation), some workers are in jobs which don’t need their particular qualification (qualification underuse), some are in jobs for which they are not qualified (underqualification), some workers are in jobs that don’t use all their skills (skills underuse) and some workers are in jobs for which they are not fully skilled (underskilling). This report uses the terms education, qualifications and skills underuse just as unemployment is understood as labour underuse: it suggests that human capital is not being used fully. Most of the literature refers to overeducation, overqualification and overskilling, which suggests that there has been excessive investment in human capital. Although different data collections and different methods of analysis make international comparisons difficult and, indeed, hazardous, Australia’s level of education, qualifications and skills mismatches seem broadly consistent with other OECD countries. The causes of skills mismatch have been much debated and there are several competing explanations. However, skills mismatch (and low levels of training) are strongly associated with casual employment. This is evident from Watson’s analysis of data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, an annual survey of 7682 households and 19 914 individuals which started in 2001. Watson (2008, p.12) fitted two regression models to the survey to find that casualised work has one of the strongest effects on skills mismatch, demonstrating that the link between contingent work and skills use is not merely due to occupational differences. He observes that the Australian workforce has become increasingly casualised during a period of strong employment growth and low unemployment levels, at least for the recent past: One of the distinguishing features of the last decade has been strong employment growth alongside an expansion in contingent employment. While much of this expansion has been underway for several decades, its persistence during a period of buoyant economic growth has been startling. Thus, whereas the unemployment rate reached an historic low of 4 per cent during this period, the underutilisation rate — which incorporates a measure of under-employment — was still above 11 per cent in 2007. Casual employment has not only grown strongly during the last two decades, but it has steadily expanded into new areas and made inroads into the full-time workforce. There has been strong growth in ‘traditional’ areas of casualisation, industries where fluctuating time periods of consumer demand or seasonal factors have pushed employers towards engaging staff in this way. However, there has also been strong growth in industries which do not fit this pattern of fluctuation or seasonality, industries like finance and insurance, where there has been a tripling of casualisation rates over this period. 2 (Watson 2008, p.16) See CEDEFOP (2010); Galasi (2008); Linsley (2005); Mavromaras, McGuinness and Fok (2010); McGuinness (2006); Messinist and Olekalns (2006, 2007); Miller (2007); Richardson et al. (2006); Ryan and Sinning (2011); Sohn (2010); and Watson (2008). NCVER 17 The uncertainty of the labour market may also undermine individuals’ and employers’ long-term investment in vocational education. We make a first attempt to analyse educational and occupational progression in the next section. 18 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations Relating educational and occupational progression Previous studies Most studies of education, qualifications and skills mismatches are of the match at a point in time, normally the time at which an employee or employer survey is conducted. There are few longitudinal studies of education, qualifications and skills mismatches because of the difficulty and expense of tracking employees or employers over an extended time. However, the HILDA Survey asks all employed respondents their level of agreement with the statement: ‘I use many of my abilities in my current job’ from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). Mavromaras, McGuinness and Wooden (2007, p.307) interpret this as a question about skills matching and classify employees who responded 1 to 3 as well matched, responses 4 and 5 as moderate skills underuse and responses 6 and 7 as severe skills underuse. (They actually use the terms severely and moderately overskilled.) Mavromaras, McGuinness and Wooden (2007, p.310) found that 9.7% of respondents who reported that many of their abilities were used in their current job voluntarily quit their job, compared with 12.1% whose abilities were moderately underused and 16.5% whose abilities were severely underused. Of those who reported that their abilities were severely underused in 2001 and quit their job, 23.6% reported that their abilities were severely underused in 2002 and 24.8% reported that their abilities were still severely underused four years later in 2005. Of those who reported that their abilities were moderately underused in 2001 and quit their job, 30.7% reported that their abilities were moderately underused in 2002 and 34.8% reported that their abilities were still moderately underused in 2005 (table 7). This suggests that skills mismatches persist in Australia. However, an anonymous reviewer of an earlier draft of this paper pointed out that these studies are based on respondents’ self-report on only one question, which is not verified by any other data in the survey. The reviewer suggested that the persistence of these respondents’ skills mismatches may reflect persisting characteristics of the respondents rather than of their underuse of skills. The reviewer also suggested that training programs may promise more sophistication in jobs than is actually the case in practice. More work is therefore needed to determine whether skills mismatches persist in Australia. However, Mavromaras and McGuinness (2007, p.281) cite UK and Canadian studies that found that skills mismatches persist in those countries. NCVER 19 Table 7 Workers who left their job in 2001 and their skills match in 2002 and 2005 % all job leavers Status in 2001 % skills severely underused % skills moderately underused % well matched Skills severely underused 23.6 10.4 11.2 13.4 Skills moderately underused 26.7 30.7 13.1 20.9 Well matched 18.9 37.7 52.4 41.4 Not employed 30.8 21.1 23.3 24.2 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 Status in 2002 Total Status in 2005 Skills severely underused 24.8 9.8 3.6 9.8 Skills moderately underused 24.0 34.8 19.1 24.7 Well matched 30.2 40.3 60.4 48.3 Not employed 21.0 15.1 16.9 17.2 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 Total Source: Adapted from Mavromaras, McGuinness and Wooden (2007, p.311, table 2). Variable career paths are also experienced by Australian trades workers. From June 2000 to October 2001 Webster and Jarvis surveyed 1125 men who were working or had previously worked in a trade in Australia. Respondents were asked to provide information on their first job and subsequent jobs at age 18, 25, 30, 35 and 40 years. Webster and Jarvis (2003, p.10) found that, of the 611 men who were 40 years or older at the time of the survey, 22% had started as an unskilled worker and had worked in a trade by the age of 40 by learning on the job. Some 21% had started in a trade and moved to a higher occupation, 21% had started and stayed in a trade, and 10% had started in a trade and moved to a lower-level occupation. Thus, the archetypical path from schooling to an apprenticeship to a trade is followed by only some tradespeople. Furthermore, as an anonymous reviewer of an earlier draft of this paper pointed out, these results confirm that it is possible to work in a trade without the formal trade qualification acquired from completing an apprenticeship or getting formal trade recognition. Martin (2007) examined the net flows of workers in occupational groups by analysing census data for 1981, 1986, 1991, 1996 and 2001. Because of a break in the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) classification of occupations in 1991 we examine only changes from 1996 to 2001. Martin (2007, p.33) constructed synthetic cohorts by taking the number of people in a five-year age cohort in an occupational group at one census and compared this with the number in the same cohort now five years older at the next census. This allowed him to calculate net flow of workers in each occupational group during the period between censuses. An extract from Martin’s (2007, p.35) results is shown in table 8. We note that only 9200 men aged 15 to 19 entered the managers and administrators group between 1996 and 2001. However, there was a substantial increase in older men becoming managers and administrators until they reached their mid-30s, when the net increase slows, and then the number leaving managerial and administrative occupations begins to increase from age 40. Women follow a broadly similar pattern, although fewer are appointed as managers and administrators. In contrast most men enter professional and associate professional occupations when young. Women also enter professional occupations when young, but there is a net outflow of women during the prime child- 20 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations bearing years of 25 to 29 and then a net increase much later than men, until the mid-40s, presumably with women re-entering professional occupations after child rearing. Men enter the trades when young, as would be expected, but after age 19 there is a steady loss of men from the trades for all older age groups. Once they leave the trades men do not appear to reenter them in large numbers (Martin 2007, p.34). As Richardson and colleagues (2006, p.17) observe about these data: ‘It is clear from this pattern that any problems with shortages of tradespeople is a problem of retention in the trades, rather than of the quantity of new entrants and levels of training’. The number of women entering a trade is only 10% of the number of men entering the trades, and their entry to the trades follows a different pattern, reflecting the different trades undertaken by women and different labour force participation due to women taking most of the responsibility for child rearing. Men enter clerical, sales and service occupations at a young age, with Martin (2007, p.34) finding evidence that they move from elementary to intermediate skill jobs within these groups up to their late 20s. Martin (2007, p.34) notes that the net outflow of men from elementary clerical, sales and service workers in the 35—39 age group (-1700), from intermediate clerical, sales and service workers (-6400) and from advanced clerical and service workers (-300) is similar to the net inflow to managerial and administrative positions for this age group (7200) and so suggests that, while managers come from a range of occupations, it is plausible that much of men’s net outflow from the three clerical, sales and service occupations after their mid-20s is due to their career progression. Martin (2007, p.34) notes that women show similar patterns to men in clerical, sales and service occupations in early career, with significant outflows from elementary occupations and entry into intermediate and advanced occupations amongst the youngest age cohort. However, women withdrew from these occupations during child-rearing years. Women’s re-entry to clerical, sales and service occupations appears to begin at the intermediate skill level, so that many probably obtain jobs at similar skill levels to those they left. However, while women re-enter these jobs until their mid-40s, it seems they do not enjoy the career progression to managerial and administrative posts experienced by men. Indeed, Martin (2007, p.34) notes that there may be a small surge in re-entry to elementary sales, service and clerical occupations amongst women in their late 40s. Martin’s synthetic cohort analysis shows broad flows of occupational progression, from which skills development and perhaps educational progression may be inferred. He conducted a very similar analysis of changes between the 1986 and 1991 censuses and found similar patterns (Martin 2007, p.34), suggesting that career progression has not changed much over 15 years. NCVER 21 Table 8 Net flows of workers into broad occupational groups by sex and age cohort, 1996—2001 Occupational group Age cohort at beginning of period 15–19 20–24 25–29 30–34 35–39 40–44 45–49 50–54 Men 1996–2001 Managers and administrators 9 200 16 900 20 300 15 400 7 200 -5 600 -19 600 -21 600 Professionals 46 700 31 300 6 600 2 500 -1 100 -7 700 -1 800 -5 300 Associate professionals 30 900 19 900 5 700 4 900 -4 600 5 200 -8 500 -10 500 Tradespersons and related workers 56 000 -18 200 -10 600 -14 800 -11 000 -6 300 -3 200 -13 400 Advanced clerical and service workers 2 400 -1 800 -1 600 -1 600 -300 -1 200 -500 -800 Intermediate clerical, sales and service workers 33 100 -6 600 -1 300 -7 000 -6 400 -1 200 -2 100 -6 900 Intermediate production and transport workers 14 500 4 700 -1 400 8 800 8 500 -2 700 -9 000 -8 700 Elementary clerical, sales and service workers -3 700 -14 200 -5 300 -3 500 -1 700 1 700 -600 -2 700 Labourers and related workers -8 700 -13 900 10 000 -8 200 -8 700 -5 300 -5 400 -1 100 Women 1996–2001 Managers and administrators 5 400 11 900 7 600 3 600 3 400 -1 500 -700 -6 800 Professionals 60 500 44 500 -3 200 8 300 8 300 3 300 -7 600 -15 500 Associate professionals 30 600 17 600 5 900 4 300 6 200 5 400 -3 100 -5 900 5 800 -4 600 -2 500 500 400 1 000 -2 800 -1 300 Tradespersons and related workers Advanced clerical and service workers 13 100 -4 400 -10 900 -5 800 0 -3 900 -6 300 -7 800 Intermediate clerical, sales and service workers 74 200 -28 800 -13 100 10 200 17 700 5 700 -5 000 -9 800 Intermediate production and transport workers -100 -2 800 -2 600 -4 300 -1 300 -2 700 -2 500 -4 900 Elementary clerical, sales and service workers -49 300 -35 200 -700 1 900 2 300 10 000 -5 000 -7 300 -1 800 -6 700 -3 300 -2 200 1 400 -3 300 -7 500 -7 200 Labourers and related workers Source: Extracted from Martin (2007, p.35, table 9). 22 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations Occupational and educational progression So far the working paper has reviewed studies of occupational progression. There is another literature on educational progression from school to vocational education and from school and vocational education to higher education. This research stream aims to investigate the relation between occupational and educational progression, which has been investigated much less. While the new Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) introduced in 2011 states that the purpose of every qualification except the highest qualification (which is the doctoral qualification) includes being ‘a pathway for further learning’ (AQF Council 2011, pp.7—10), this is a recent requirement and is not yet strongly implemented in vocational education. Therefore, although Australian vocational qualifications may be strongly linked to their corresponding jobs, they are not necessarily strongly linked to other qualifications. This is illustrated schematically in figure 1, where a larger and heavier arrow indicates a strong relation, and a smaller and finer arrow indicates a weak relation. Possible exceptions to this pattern are so called ‘nested programs’, where, for example, a certificate III forms part of its corresponding certificate IV. Figure 1 Vocational education’s internal relations and relations with work Certificate IV Certificate IV job Certificate III Certificate III job In contrast, higher education programs are based on disciplinary knowledge or applied disciplinary knowledge and most programs in each field are strongly related to other programs in the field, often sequentially based on a hierarchy of knowledge. However, most higher education programs are not as strongly related to a corresponding job as vocational programs. So, while higher education programs may be strongly linked to other higher education programs, they are not necessarily strongly linked to work. This is illustrated schematically in figure 2. Figure 2 Higher education’s internal relations and relations with work Bachelor Bachelor job Diploma job Diploma An exception is nursing, where the diploma of nursing (enrolled/division 2 nursing) is strongly related occupationally to enrolled nursing and also educationally to the bachelor of nursing, which in turn is NCVER 23 strongly related occupationally to registered nursing. There is therefore a strong educational progression from the diploma of nursing to the bachelor of nursing that corresponds to a strong occupational progression from enrolled nursing to registered nursing (figure 3). Figure 3 Nursing’s educational and occupational relations Bachelor of nursing Diploma of nursing Registered nurse Enrolled nurse In the wider health areas, though, there is not a strong relation between the diploma of nursing and any antecedent program, such as the certificate III in aged care, and therefore there is no strong occupational progression from personal care worker to enrolled nurse. Indeed, it is possible to work as a personal care worker without a formal qualification (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations 2011b). Nor is there a strong relation between the bachelor of nursing and the bachelor of medicine/bachelor of surgery and so there isn’t a strong occupational progression from registered nurse to medical practitioner (figure 4). The strong interrelations between the diploma and bachelor of nursing and enrolled and registered nursing seem to sit as a microcosm or a mini skills ecosystem within health programs and occupations, which are no better linked than other cognate programs and occupations. Figure 4 Educational and occupational relations in some health fields Bachelor of medicine/bachelor of surgery Medical practitioner Registered nurse Enrolled nurse Personal care worker Bachelor of nursing Diploma of nursing Certificate III in aged care A key issue for this project is therefore: is it possible to construct the relationships between programs and occupations to give strong educational and occupational progression such as there is with nursing, or is nursing exceptional and unable to inform educational and occupational progression in other fields? For example, might it be possible to strengthen the educational and occupational progressions 24 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations from employment as an accounts clerk, which might be learned on the job or in a certificate IV or diploma of accounting, to a bachelor of accounting, preparing graduates for employment as an accountant and the relevant occupational membership? NCVER 25 Discussion There are competing explanations of the relation between qualifications and occupations, which suggest different approaches to constructing the relation between education and work. Cully and colleagues (2006, p.9) observe that: The interaction between education and training on the one hand, and the labour market on the other, is complex. The Australian labour market is sophisticated and highly flexible — occupations in demand are in constant flux, adjusting to changing consumer demand and changing ways of conducting business. On the supply side, there is a great deal of movement of people between jobs, and movement in and out of the labour force. (Cully et al. 2006, p.9) Arguably, the dynamism and complexity of the interaction between education and the labour market would thwart any attempt towards systematic reform. However, the relation between education and occupations has been persistently problematised by employers, who complain about what they call ‘skills shortages’, while employees and their representatives have long been concerned to improve the employment prospects of people who are unemployed, underemployed, employed casually and who are in unrewarding jobs without obvious prospects of advancement. It therefore seems worth exploring the relation between qualifications and occupations to suggest options to ameliorate these problems. In its roadmap for vocational education and training, Skills Australia (2011, p.45) proposes ‘a broader focus on workforce development and skills use, rather than a more traditional focus simply on training and skills formation’. Skills Australia (2009, p.3) says that: A workforce development approach is characterised by policies and practices which support people to participate effectively in the workforce and to develop and apply skills in a workplace … where learning translates into positive outcomes for enterprises, the wider community and for individuals throughout their working lives. (Skills Australia 2009, p.3) Skills Australia’s interest in workforce development (that is, how an industry attracts, retains and skills workers) was stimulated by its observation of employers’ extensive underuse of skills (Skills Australia 2011, p.32) and of unemployment (Skills Australia 2011, p.23) during a period when employers are experiencing so-called skills shortages, with some employers such as miners reluctant to recruit inexperienced although qualified workers. It recommends: amalgamation of a range of enterprise-linked funding programs into a new industry-driven funding program for workforce development establishment of an industry-led advisory body to guide the new funding program redesign of the apprenticeship model and employer incentives to stimulate a broader focus on workforce development, to be brought under the auspices of the new funding program and advisory body simplification and redesign of services for employers, apprentices and trainees, to be brought under the auspices of the new funding program and advisory body. [Earlier] we proposed moving individual and enterprise funding to a demand-based approach. [Here], we detail the proposals for an industry-driven fund to encourage approaches to workforce development and also reduce the risk of a possible mismatch between student choices and industry skills requirements. 26 (Skills Australia 2011, p.45) The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations While Skills Australia (2011, p.45) says that, ‘The object of the enterprise funding stream is to improve the connection between enterprise workforce development needs and the provision and development of skills’, it recommends that the workforce development fund be ‘industry-driven’ to complement student entitlements and thus the student demand-driven funding it proposed for core vocational education funding (recommendation 1, p.43). Skills Australia seems to be proposing two parallel systems: a training system that would respond to student demand and a workforce development system which would be led by employers. This hardly seems likely to improve the connection between the supply and demand for skilled workers sought by Skills Australia. To integrate training and workforce development, a single training and workforce development system would be required, one that was responsive to students but which had the shared involvement of teachers, employers and employees. Brockmann, Clarke and Winch (2009, p.103, citing Rauner 2004, 2007) outline three models of the relation between qualifications and occupations. In their ‘skills based model’ the capacity of each individual is measured by the performance of narrowly specified skills in employment, irrespective of how these skills were acquired. Brockmann and colleagues found bricklaying and truck driving in England to be in this first family of qualifications. This is closest to Australia’s current provision of vocational education. The second is the ‘employability model’, in which employers’ primary entry criterion is a high level of general education, with employees building their stock of skills in response to labour market demands. This was seen to be the dominant model across the ICT sector, where ‘self organised learning’ within enterprises was common. Development of a broad notion of the application of knowledge and skill remained critical, including social and personal applications. Australia’s higher education is currently closest to this model. Third is the ‘vocational education’ model in nursing in France, England, Germany and the Netherlands. In this model social partners regulate learning content, occupational entry and integration with the education and training system, and a broad notion of occupational competence is upheld. The uncertainty of the labour market may lead to a diminution of occupational identity. Casual employment, having more than one job concurrently and changing jobs frequently may reduce people’s identification with a particular occupation. But Dostal (2009, p.168) argues that: ‘The declining stability of employment structures and the growing mobility of job holders reduces [sic] identification with employers and strengthens identification with occupation’. This suggests further problems with an ‘employer led’ system of vocational education and that these may be overcome by developing people’s attachment to a vocation. Dostal proposes that vocational education and employment be organised into 12 broad vocational disciplines, specified by occupational fields or families. Dostal (2009, p.165) says that: From the point of view of vocational training those occupational areas or fields are of far higher significance than single occupations and they characterise the stability of the occupational landscape in the long run. We call Dostal’s occupational areas ‘vocational streams’ (Buchanan et al. 2009, p.29). These encapsulate a broader notion of vocation, one which allows people to accrue skills coherently and cumulatively and which prepares them for work in a range of occupations at a range of levels. A good example of a vocational stream is modern logistics. It often involves production workers using kan ban (just in time) systems as well as those in warehouses, transport and those taking delivery of the good or service. Other vocational streams appear to operate in care work, customer service, engineering, business services and information technology (Buchanan et al. 2009, p.29). NCVER 27 A somewhat different approach is the vocational principle (Berufskonzept) that informs Germany’s vocational education. The German concept of a vocation is broader than the Anglo concept of an occupation and signifies ‘a body of systematically related theoretical knowledge (Wissen) and a set of practical skills (Können), as well as the social identity of the person who has acquired these’ (Streeck 1996, p.145, cited in Clarke & Winch 2006, p.262). Achievement of such an identity depends on passing an examination and is certified by a qualification, which is recognised by all employers and associated with a particular status, wage grade and social value (Clarke & Winch 2006, p.262). A vocation (Beruf) integrates three domains, which are segmented in Anglo societies: occupational standards, educational standards and the labour market (Hellwig 2005, p.2, citing Deissinger 1998, p.248). Thus, Germany’s federal law on vocational education defines about 350 apprenticeships (Ausbildungsberufe). Employees, employers, government authorities and other social partners define the occupational standards of each vocation. Vocational colleges (Berufsschulen) and employers train apprentices to meet the relevant occupational standards defined by a federal law, following a curriculum and on-the-job training specified by a state law and monitored by regional chambers of commerce. Employers recruit staff in each vocation, confident of the skills and knowledge that members of the vocation have, while employees know that membership of a vocation makes them employable in that vocation by employers in a wide range of contexts (Ertl 2006, p.112). The German vocational principle also integrates three levels of governance: the federal level, which establishes a stable organisational and political framework; the state (Land) level, which specifies curriculum and pedagogy; and the regional level, which monitors adherence to educational standards (Hellwig 2005, p.3, citing Deissinger 1998, pp.183, 251). A broader approach is to consider vocational education and occupational progression as developing people’s capabilities. ‘Capabilities’ and ‘capacities’ are often used in the higher education literature to distinguish them from the general or employability skills distinctive of vocational education. This paper adopts the broader notion of capabilities as developed by Sen (1999) and Nussbaum (2000). Sen (1993, p.47) and Nussbaum (2000, pp.292—8) describe capabilities as what people are able to be and do and they argue for the construction of resources and social arrangements to support them. Sen and Nussbaum go beyond individual attributes, which are often the subject of the higher education capabilities literature, to consider the social, economic and cultural conditions that are required to realise capability. Sen and Nussbaum distinguish between capabilities and functionings. Capabilities refer to people’s capacity to act, while achieved functionings refer to the outcomes that ensue when they choose to use their capabilities to achieve a particular goal. A complex set of capabilities provides individuals with the basis for making choices in their lives, whereas functionings are the outcomes when they exercise choice. A particular set of capabilities can produce any number of outcomes. Walker and Unterhalter (2007, p.4) explain that: ‘The difference between a capability and functioning is one between an opportunity to achieve and the actual achievement, between potential and outcome’. Sen (1993, p.31) distinguishes between functionings and capabilities in this way. Two people with similar capabilities may make choices that result in different functionings or outcomes. Sen’s human capability is different from human capital: At the risk of oversimplification, it can be said that the literature on human capital tends to concentrate on the agency of human beings in augmenting production possibilities. The perspective of human capability focuses, on the other hand, on the ability — the substantive freedom — of people to lead the lives they have reason to value and to enhance the real choices they have. The two perspectives cannot but be related, since both are concerned with the role of 28 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations human beings, and in particular with the actual abilities that they achieve and acquire. But the yardstick of assessment concentrates on different achievements. (Sen 2001, p.99) A capabilities approach may help to provide more curricula coherence between vocational and higher education and thus support pathways and help to overcome discontinuities in flows in education, particularly if both seek the development of practitioners capable of autonomous reasoning (Buchanan et al. 2009). NCVER 29 Conclusion The paper opened by reviewing the data available on student transfers in tertiary education, which found that most transfers are within vocational or higher education, not between the sectors. It then reviewed some of the research, which has found that there is not a close match between tertiary education and occupations. About 30% of workers seem to be in jobs not well matched to their years of education, qualifications or skills. This seems to be the case for all tertiary education except that which prepares graduates for licensed occupations such as electrician or physician and seems to apply to many countries, including Australia. While this may be expected for higher education, particularly in the liberal arts and sciences, which give students a general academic education, it is unexpected and may be problematic for Australian vocational education, which is based on developing workplace competences. The paper then reviewed some of the limited longitudinal studies of Australian workers’ changes in occupation to find some patterns of occupational progression; however, many more changes that do not seem to follow a pattern were found. The paper proposed an analytical framework to consider occupational and educational progression based on the educational and occupational progression from diploma of nursing, leading to an enrolled nurse, to bachelor of nursing, leading to a registered nurse. Finally, the paper considered competing explanations of the relation between qualifications and occupations, which suggest different approaches to constructing the relation between education and work. The research team plans to explore these approaches, developing the most promising model for building pathways within and between education and work. One possibility may be to investigate associate degrees, which are relatively new in Australia and where enrolments have increased greatly in the last six years, from just under 1000 equivalent full-time students in 2004, to 6600 equivalent full-time student load in 2010. Higher education associate degrees may be displacing vocational diplomas as a different kind of ‘cross over’ qualification (Karmel & Nguyen 2003) between intermediate and professional occupations. They may also be a bridge between lower- and higherlevel tertiary qualifications. The research team invites comments on the issues raised in the paper. Acknowledgment We thank an anonymous reviewer of an earlier draft of this paper, all of whose helpful suggestions have been incorporated in the paper. 30 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations References ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2005, Information paper: ANZSCO — Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations, cat.no.1221.0, ABS, Canberra. Australian Qualifications Framework Council 2011, Australian Qualifications Framework 2011, viewed 26 April 2011, <http://www.aqf.edu.au>. Brockmann, M, Clarke, L & Winch, C 2009, ‘Difficulties in recognising vocational skills and qualifications across Europe’, Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, vol.30, no.1, pp.97—109. Buchanan, J, Yu, S, Marginson, S & Wheelahan, L 2009, Education, work and economic renewal: an issues paper prepared for the Australian Education Union, Workplace Research Centre, University of Sydney, viewed 26 August 2009, <http://www.aeufederal.org.au/Publications/2009/JBuchananreport2009.pdf>. CEDEFOP 2010, The skill matching challenge: analysing skill mismatch and policy implications, European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, Luxemburg, viewed 14 February 2011, <http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/EN/Files/3056_en.pdf>. Clarke, L & Winch, C 2006, ‘A European skills framework? But what are skills? Anglo-Saxon versus German concepts’, Journal of Education and Work, vol.19, no.3, pp.255—69. Cully, M, Delaney, M, Ong, K & Stanwick, J 2006, Matching skill development to employment opportunities in New South Wales, viewed 24 April 2011, <http://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv30844>. Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) 2008, 2009 data elements by file/name/number, viewed 18 May, 2011, <http://www.heimshelp.deewr.gov.au/11_HE_Student_Data_Collection/2009_SDC_Requirements>. ——2009, Training package development handbook, viewed 4 February 2011, <http://www.deewr.gov.au/Skills/Overview/Policy/TPDH/Pages/default.aspx>. ——2011a, Training package development handbook, viewed 25 April 2011, <http://www.deewr.gov.au/Skills/Overview/Policy/TPDH/CompetencyUnits/Pages/Overview.aspx>. ——2011b, ‘Job guide: personal care attendant’, viewed 26 April 2011, <http://www.jobguide.thegoodguides.com.au/occupation/view/423111A>. Deissinger, T 1998, Beruflichkeit als „organisierendes Prinzip“ der deutschen Berufsausbildung, Eusl, Markt Schwaben. Dostal, W 2009, ‘Occupational research’, Handbook of technical and vocational education and training research, eds F Rauner and R MacLean, Springer, Dordrecht, pp.162—8. Ertl, H 2006, ‘The overseas case as a political argument: the reception of NVQs (national vocational qualifications) in Germany’, in Cross-national attractions in England: accounts from England and Germany, ed. H Ertl, Symposium Books, Oxford, pp.103—25. Galasi, P 2008, ‘The effect of educational mismatch on wages for 25 countries’, Budapest working papers on the labour market, viewed 14 February 2011, <http://econ.core.hu/file/download/bwp/BWP0808.pdf>. Hellwig, S 2005, ‘The competency debate in German VET research: implications for learning processes based on vocationalism’, paper presented to the 2009 conference of the Australian Vocational Education and Training Research Association, Brisbane, viewed 28 April 2011, <http://avetra.org.au/publications/ conference-archives/conference-archives-2005/conference-papers>. Karmel, T & Nguyen, N 2003, ‘Australia’s tertiary education sector’, Centre for the Economics of Education and Training 7th National Conference, Monash University, Melbourne. Karmel, T, Mlotkowski, P & Awodeyi, T 2008, Is VET vocational? The relevance of training to the occupations of vocational education and training graduates, NCVER, Adelaide, viewed 19 February 2011, <http://www.ncver.edu.au/publications/2013.html?friendly=printable>. Linsley, I 2005, ‘Causes of overeducation in the Australian labour market’, Australian Journal of Labour Economics, vol.8, no.2, pp.121—43. Martin, B 2007, Skill acquisition and use across the life course: current trends, future prospects, NCVER, Adelaide, viewed 14 May 2011, <http://www.ncver.edu.au/publications/1747.html>. Mavromaras, K, McGuinness, S & Fok, YK 2010, The incidence and wage effects of overskilling among employed VET graduates, NCVER, Adelaide, viewed 21 January 2011, <http://www.ncver.edu.au/publications/2231.html>. Mavromaras, K & McGuinness, S 2007, ‘Education and skill mismatches in the labour market: editors’ introduction’, Australian Economic Review, vol.40, no.3, pp.279—85. NCVER 31 Mavromaras, K, McGuinness, S & Wooden, M 2007, ‘Overskilling in the Australian labour market’, paper in ‘Policy forum: education and skill mismatches in the labour market’, Australian Economic Review, vol.40, no.3, pp.307—12. McGuiness, S 2006, ‘Over education in the labour market’, Journal of Economic Surveys, vol.20, no.3, pp.387—418. Messinist, G & Olekalns, N 2006, ‘Training and returns to undereducation and overeducation: new Australian evidence’, paper presented at the 35th Australian Conference of Economists, Curtin University of Technology, Perth, 25—27 September, viewed 6 March 2011, <http://www.business.curtin.edu.au/files/messinis_olekalns.pdf>. ——2007, ‘Skill mismatch and training in Australia: some implications for policy’, Australian Economic Review, vol.40, no.3, pp.300—6. Miller, P 2007, ‘Overeducation and undereducation in Australia’, Australian Economic Review, vol.40, no.3, pp.292—9. Nussbaum, M 2000, Women and human development: the capabilities approach, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge [Kindle DX version]. Rauner, F 2004, Praktisches Wissen und berufliche Handlungskompetenz, ITB Forschungsberichte 14/2004 [Practical knowledge and occupational action competence, Research report 14/2004], University of Bremen, Bremen. ——2007, ‘Vocational education and training — a European perspective’, in Identities at work, eds A Brown, S Kirpal & F Rauner, Springer, Dordrecht, pp.115—44. Richardson, S, Tan, Y, Lane, A & Flavel, J 2006, Reasons why persons with VET qualifications are employed in lower skilled occupations and industries, National Institute of Labour Studies, Flinders University, Adelaide, viewed 7 March 2011, <http://nils.flinders.edu.au/assets/publications/Reasons_why_Persons_with_the_VET.pdf>. Ryan, C & Sinning, M 2011, Skill (mis)matches and over-education of younger workers, NCVER, Adelaide, viewed 11 January 2011, <http://www.ncver.edu.au/publications/2330.html>. Sen, A 1993, ‘Capability and well-being’, in The quality of life, eds M Nussbaum & A Sen, Oxford University Press. ——1999, Development as freedom, Anchor Books, New York. ——2000, ‘Social exclusion: concept, application and scrutiny’, Asian Development Bank, viewed 25 January 2011, <http://www.adb.org/documents/books/social_exclusion/Social_exclusion.pdf>. ——2001, Development as freedom, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Skills Australia 2009, ‘Workforce futures overview paper’, Papers to promote discussion towards an Australian workforce development strategy, Skills Australia, Canberra, viewed 2 November 2009, <http://www.deewr.gov.au/Skills/Programs/skillsaustralia/Documents/WorkforceFuturesOverview1.pdf>. ——2011, Skills for prosperity — a roadmap for vocational education and training, Skills Australia, Canberra, viewed 3 May 2011, <http://www.skillsaustralia.gov.au>. Sohn, K 2010, ‘The role of cognitive and noncognitive skills in overeducation’, Journal of Labor Research, vol.31, pp.124—45. Streeck, W 1996, ‘Lean production in the German automobile industry: a test case for convergence theory’, in National diversity and global capitalism, eds S Berger & R Dore, Cornell University Press, New York, pp.138—70. Walker, M & Unterhalter, E 2007, ‘The capability approach: its potential for work in education’, in Amartya Sen’s capability approach and social justice in education, eds M Walker & E Unterhalter, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp.1—18. Watson, I 2008, ‘Skills in use: labour market and workplace trends in skills use in Australia’, paper presented to Jobs Australia national conference, 8 September, Brisbane, viewed 6 March 2011, <http://www.ianwatson.com.au/pubs/watson_skills_paper_handout.pdf>. Webster, E & Jarvis, K 2003, ‘The occupational career paths of Australian tradesmen’, Melbourne Institute working paper number 14/03, viewed 14 May 2011, <http://repository.unimelb.edu.au/10187/955>. Winch, C 2010, ‘Vocational education, knowing how and intelligence concepts’, Journal of Philosophy of Education, vol.44, no.4, pp.551—67. 32 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations Support document details Additional information relating to this research is available in The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations: support document. It can be accessed from NCVER’s website <http://www.ncver.edu.au/publications/2537.html>. It explores available data and their usefulness in understanding patterns of movement and student outcomes within education, and between education and work. NCVER 33 NVETR Program funding This work has been produced by NCVER under the National Vocational Education and Training Research (NVETR) Program, which is coordinated and managed by NCVER on behalf of the Australian Government and state and territory governments. Funding is provided through the Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education. The NVETR Program is based on priorities approved by ministers with responsibility for vocational education and training. This research aims to improve policy and practice in the VET sector. For further information about the program go to the NCVER website <http://www.ncver.edu.au>. The author/project team was funded to undertake this research via a grant under the NVETR Program. These grants are awarded to organisations through a competitive process, in which NCVER does not participate. 34 The role of educational institutions in fostering vocations