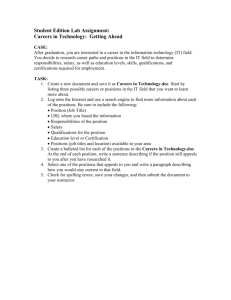

guidance and learner autonomy

advertisement