A thorough study of financial services for the poor should begin by

advertisement

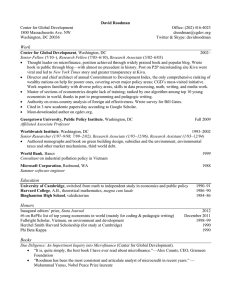

Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 Chapter 2. How the Other Half Finances If I had my way I would write the word “Insure” over the door of every cottage, and upon the blottingbook of every public man, because I am convinced that by sacrifices which are inconceivably small, which are all within the power of the very poorest man in regular work, families can be secured against catastrophes which otherwise would smash them up for ever. — Winston Churchill, 19091 I believe that all human beings are potential entrepreneurs. Some of us get the opportunity to express this talent, but many of us never get the chance because we were made to imagine that an entrepreneur is someone enormously gifted and different from ourselves. — Muhammad Yunus, 20042 Perhaps you remember when you first learned about microcredit. Did it surprise you that one could help the poor by putting them in debt? The root of that surprise is the microfinance movement’s success in replacing, in the public mind, the old story of lending to the poor—on one of usury and entrapment— with a new one: after all, it seems, the poor are not so locked in by the lack of money that credit will only stave off hunger for a few weeks, then leave a residue of hopeless liabilities. Instead, the poor are masters of their fates, incipient entrepreneurs who only lack credit to bloom. Of course, each of the stories is true sometimes, and neither is true always. Thus is an irony in this modern myth-remaking. The microfinance movement has rightly been animated by a belief that the poor are no less creative or ambitious for being poor. But to live up to that spirit of respect, we ought to minimize our preconceptions about how the poor do and ought to use financial services. Let us define the global rich as the billion or so people who live in relative material comfort and security. If you belong to this group, you can see that your peers are a diverse group, using financial services such as savings and loans and insurance in diverse ways with diverse outcomes. The experiences of the 5 billion or so poor people are at least as varied. Some get trapped in debt. Others, whom we call microentrepreneurs, do borrow money to stock up their corner stores or invest in goats. But even those two stories are not the “whole story.” A family might save to prepare for a wedding, buy insurance to dampen the feared shock of a father’s death, or borrow for antibiotics for an ill son. 1 2 Churchill (2007 [1909]), 146–47. Yunus (2004), 207. 1 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 Poor people, like everyone else, want financial services for many purposes in addition to starting a business. If anything, in fact, people living close to the jagged financial edge need financial services more than the rich. Unfortunately, and inevitably, while the better-off can usually find services tailored to specific needs, from mortgages to life insurance to retirement accounts, those less fortunate must choose from lower-quality options, which thus are often not well matched to the needs at hand. As the authors of the seminal 2009 book Portfolios of the Poor have shown, the poor must patch together unreliable or inflexible services—loans from friends, store credit, neighborhood savings clubs, and microcredit—to manage money as best they can.3 This book asks what microfinance does for the poor. Let us start our investigation from the client’s point of view. How the rich use financial services The global rich have access to a spectacular variety of financial services: checking and savings accounts, home mortgages, car loans, credit cards, mutual funds, retirement funds, brokerage accounts, insurance for cars, houses, health, life, and disability….Just as it is hard for a New Yorker who samples a new restaurant each week to ken the life of a Guatemalan highlander subsisting on tortillas, so is it hard for those who enjoy a wealth of financial services to empathize with a woman for whom saving means hiding money from her husband in the folds of her sari. Despite the gulf in experience, the rich can gain insight into the poor’s use of financial services by contemplating their own. Try this exercise. List all the financial services you have used. For each, determine what it helps you do. Transact? Invest? Spend money you have not yet earned? Then confront this question: if you had to give up all these services but one, which would you keep? Here is my full list. It is fairly representative for middle-class American families; but even if you consider yourself part of the same group, your list will probably differ: 3 Collins et al. (2009). 2 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 Table 1. My financial services Service Purpose Savings account Prepare for emergencies such as job loss Checking account Transact over long distances or in large amounts without cash Wire transfer Send and receive money internationally (rare) PayPal account Send money to friends; buy things online Credit cards Transact without cash; buy things I want before I have the money Home mortgage Live in a home I own before I can pay for it Home equity line of credit Ditto; and cheap credit to improve house Car loan Get a car before I can pay for it Student loan Invest in my own skills, for higher pay after graduation College savings Prepare to do the same for my sons Retirement savings Prepare to support myself when I no longer work Health insurance Protect family against financial catastrophe in event of serious health problems; assure access to care Homeowner’s insurance Protect family against financial catastrophe in event of serious harm to home Automobile insurance Protect family against financial catastrophe in event of serious harm to car, or liability for accident Umbrella liability insurance Protect family from liability suits in general Life insurance Protect family against financial catastrophe if I die Disability insurance Protect family against financial catastrophe if I am unable to work If you I showed and explained this list to a microfinance client, the luxury would become obvious—the variety and low cost of the services, the college education foreseen, the home valued in six figures. But if I articulated the needs that underlie my use of these services, we might understand each other well. In scanning the list, I discern four major and universal purposes: 1. To transact. The credit cards and checking account help me move sums too large to be safe in my wallet. They also help me send amounts large and small over long distances. And they make it all easy. My paycheck goes into the checking account automatically; the mortgage payment comes out just as smoothly. A swipe of a card at the pump pays for gas. 2. To invest. I need to sacrifice now to have more later. I borrowed to help pay my college tuition, and I invest in a fund to do the same for my two sons. Notably, like most people in rich 3 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 countries, I have not used financial services to invest in my own business, for I have none. I prefer the stability of the salaried job I am fortunate to hold. 3. To build assets. Notice what I did not mention just above under the heading of investment: buying a house: Some people ascribe an investment purpose to the home mortgage. But I bought my house for other reasons. In fact, on general principles, a mortgage-financed home is a terrible investment. It puts a lot of financial eggs in one basket, violating the principle of diversification. Using credit to buy the home—investing with leverage—multiplies the risk as housing market crashes and foreclosure epidemics have made obvious in several countries. And homes can be hard to sell ( “illiquid” in investmentspeak). Why then make such a terrible investment decision? Owning a home (or bicycle or cow) brings a degree of security.. Someone who holds title to her home need not worry about being forced out by a landlord who does view the building as an investment. Home ownership also strengthens communities by increasing the interdependence: what one neighbor does to her property affects the value of others’. A more collective view encourages people to work together on local institutions such as schools. And secure people think longer-term: a farmer is more apt to husband land he owns than land he leases. Finally, as Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto has famously argued, title to a major asset can also serve as collateral for credit.4 I once borrowed against my house to fix the roof, and could borrow again as another way to help put my sons through college. 4. To sustain consumption. I was struck to discover that most of the services on my list serve to secure my family’s access, through thick and thin, to necessities such as food and clothing. The savings account is a safety net if I lose my job. Retirement savings should let me buy what I need when I earn nothing. Credit cards and the home loans let us marshal big sums 4 de Soto (2000). 4 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 without starving. The insurance policies take the financial bite out of life’s traumas.5 Economists call this function consumption smoothing. And to respond to the challenge I posed earlier, if I was told I had to live with just one financial service, I would beg for two, both of which smooth consumption: life and health insurance. They protect my family from bankruptcy in the face of life’s worst. We can learn more lessons from this exercise. First, risk is intimately intertwined with money. Insurance policies put risk front and center. But they are not unique in involving it, for whenever one party to an agreement to provide financial services commits to delivering money under certain circumstances at some future date, there is risk. Perhaps a borrower will not repay, or a bank holding deposits will go under. Second, many financial services bind even as they serve. The mortgage and other loans force me to set aside money each month to make the payments. Before retirement, the retirement accounts can only be accessed at a penalty. In appropriate doses, this discipline is healthy; we all need help resisting the temptation to fritter away today. Of course, sometimes discipline becomes punitive. This double-edged nature, of credit especially, is the germ of the ancient and unresolved debates over precisely what constitutes just lending. Third, the set of financial services you use depends on who you are. If I were a poor American, my inventory would be quite different. I might not have the steady job that makes me an attractive risk to mortgage lenders. My compensation might not include a retirement plan. I might have trouble maintaining a minimum balance in a checking or savings account. And, to borrow a term from the Commission on Thrift, a coalition of U.S. non-profits, the “concierge services” of government-subsidized retirement and college savings accounts would probably disappear from my list.6 So might all the insurance policies and the checking account. In their place might appear check cashers and payday lenders 5 Perhaps I should also have listed the government insurance programs my employer pays into on my behalf, to aid me when I retire, or before then if I lose my job. 6 Commission on Thrift (2008). 5 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 extending credit at 400 percent per annum. Just as there are more drugs for male impotence than malaria, the financial services available to the rich outshine those within reach of the poor—in quality, diversity, and cost. This too is worth noting: my wife’s inventory is identical to mine. But in many countries, law and custom keep women out of formal finance. Perhaps the most important lesson from this exercise is about how financial services, like roads and piped water, undergird the comfortable life. Imagine having to conduct your life without financial services: no bank accounts, no bank loans, no credit cards, no insurance, not even payday loans…just cash. The intangibility of these services belies their importance. Their chief benefit, I would argue, is in serving the purpose on my list: helping people manage and maintain consumption during lean seasons and catastrophes. In the vocabulary of Amartya Sen, financial services give people more agency, more control over their lives—more freedom. However, as Sen emphasizes, freedom begets freedom. Those who already have more agency, thanks to being rich or male, say, can access better services.7 Those who come to the financial service marketplace with fewer advantages leave with fewer. The financial challenges of the poor In comparing and contrasting the rich and the poor, the famous exchange between F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway comes to mind. “The rich are different from us,” Fitzgerald observed. “Yes,” retorted Hemingway, “they have more money.” Actually, that never happened. The story is a Hemingway fiction, a put-down of his rival’s fascination with the rich.8 But this apocryphal exchange does capture a real question for us: is there much difference between being rich and being poor? When it comes to solving financial problems, are rich the same as poor, except with more money? 7 8 Sen (1999). Berg (1978), 304–05. 6 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 Yes and no. Broadly, rich and poor are no different: all need to transact, invest, build assets, and sustain consumption. On the other hand, the financial circumstances of the poor are qualitatively, not just quantitatively, distinct. Their needs, especially to sustain consumption, are more acute, and the strategies they use to meet those needs are in several respects quite different. Poor families, for example, are more apt to dispatch members to find work. Migrating for work can increase earnings as well as smooth them through spatial diversification. Living in 1995–96 in a village in southern Bangladeshi served by the Grameen Bank, graduate student Sanae Ito discovered that the surest way for residents to get out of poverty in that village was to get out of the village. A family would save up or borrow to send a spouse or child to the capital, Dhaka, to do day labor or even get a job.9 In Kenya, the wildly popular mobile phone–based money transfer service, M-PESA, got its start with the slogan “Send Money Home.” The target client lived in Nairobi and needed safe ways to send funds to his parents, wife, or children in the countryside.10 Bangladeshi and Kenyan villages also export workers even farther afield. Bangladeshi men working construction and other jobs in the Middle East are sending macroeconomically significant flows of money homeward. Many Kenyans go to the U.K. Companies such as Western Union and MoneyGram help these workers remit funds across borders. In Bangladesh, BRAC Bank, a spin-off of the giant non-profit BRAC, has teamed up with Western Union to turn its branches into money transfer points. In Kenya, Safaricom, the creator of M-PESA, is working to bypass money transfer major by extending its network internationally. (See Figure 1.) Already, amazingly, M-PESA does more transactions domestically than Western Union does globally.11 9 Ito (1999). Mas and Radcliffe (2010), 9. 11 Ibid. 10 7 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 Figure 1. Posters for international money transfer through BRAC Bank and Western Union in Bangladesh and through M-PESA in Kenya (Photos by author) Another precarious aspect of poverty is the difficult of obtaining and protecting major assets. The poor, like the rich, can benefit immensely from the security that comes with owning farm land or a house. But obtaining such things and protecting them from flood, fire, and theft is a more fraught enterprise. One can see the importance of asset ownership for the poor in an incident in Argentina. In 1984, the government of Buenos Aires moved to give 1,800 squatter families on the outskirts of the city title to land on which they lived. Eight of the 13 legal owners of the land accepted the city’s buyout, while the rest fought the expropriation in court for twenty years. Thus some squatters lucked out in quickly gaining title while others did not—a circumstance which, however cruel and arbitrary, made gold for re- 8 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 searchers, in the form of a “natural experiment.”12 The Wall Street Journal sketched the consequences for the squatters: Mercedes Almada and Valentín Orellana both live in San Francisco Solano, a barrio settled by squatters almost 25 years ago on the fringes of the Argentine capital. They established households on identically sized lots and worked similar blue-collar jobs for comparable wages—she in sewing, he in a factory. They endured the same hardships, including an effort by Argentina's 1980s military government to bulldoze the settlement. Then, Mrs. Almada gained title while Mr. Orellana did not. Today, Mrs. Almada lives in a neat colonial-style home with a slab roof supported by pillars as solid as oaks. The six members of the Almada household have rooms of their own. A daughter finished high school and one son finished technical school. Mr. Orellana’s house is made of rough looking cinder blocks and concrete, with thin posts supporting a corrugated zinc roof. It is so cramped that some of the eight family members have to sleep in the dining room and kitchen. None of the children [has] made it past seventh grade.13 The reporter may have chosen extreme examples to show the fork in fates. But statistics back up the vignette. Argentine researchers Sebastian Galiani and Ernesto Schargrodsky found that title-holders invested more in their homes and the education of their children.14 Thus we see that the poor, like the rich, need to build assets, just as they need to transact over long distances. But their needs have a different timbre. The same goes for the other two purposes I identified in inventorying my financial services: The poor also try to invest for the future. And above all they strive to assure steady access to necessities despite life’s vicissitudes. But here the rich-poor difference is so great that to view poor people as rich people with less money is to completely misunderstand their financial lot. The poor are short of money, yes, but also of control over their financial circumstances. Their incomes and spending needs are more variable and unpredictable, their lives more dangerous. Perhaps the most important financial distinction between poor and rich—leaving aside the superrich—is that by and large the rich have salaries. My steady paycheck 12 Galiani and Schargrodsky (2005). Moffett (2005). 14 Galiani and Schargrodsky (2005). 13 9 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 rivals all my insurance policies in bestowing financial security. It allows me to think long-term, helping me invest in, among other things, my children. And it makes me more creditworthy, helping me borrow to build up assets. Surveying findings from household surveys done in 13 developing countries, MIT economists Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo found that what most statistically distinguished people earning more than $2 a day from those living on less was not education or health, or even wealth, but holding a steady job.15 To put that another way, as I wrote in chapter 1, most people who live on $2 a day don’t live on $2 a day: they earn $4 one day, $1 the next, $3 the day after that, and so on. Or perhaps they make money once a season, when they sell their crops. Characterizing poor people as earning some number of dollars per day thus misses the fundamentally different nature of their income. The variability matters at least as much as the average. No work has made this reality clearer to the world’s salaried minority than Portfolios of the Poor, the book by Darryl Collins, Jonathan Morduch, Stuart Rutherford, and Orlanda Ruthven. Following a suggestion some ten years ago by the University of Manchester’s David Hulme, Rutherford and other researchers began working with a few dozen families in Bangladesh to collect detailed financial transaction logs called financial diaries. Later work extended the methodology to a few hundred families in India and South Africa. Typically, a researcher visited a household every two weeks over the course of the year to update the logs, noting down every day wage and rice purchase, every instance of saving, borrowing, and repayment. Among the stories revealed in the diaries, and in the book, is that of Pumza, who cooks and sells sheep intestines out of a stall in Cape Town. Net of spending on firewood and raw intestines, Pumza makes $95 a month on average; adding a $25 child support grant brings her monthly income to $120, which works out for Pumza and her four children to $0.80 per person per day. 15 Banerjee and Duflo (2008). The authors use purchasing power parities to convert to U.S. dollars. 10 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 Hidden within that average, however, is a great deal of unpredictability and volatility—day to day, month to month. (See Figure 2.)16 Figure 2. Fortnightly revenues, expenses, and profits of Pumza, March 20–November 27, 2004 $100 $90 Revenues $80 Profits $70 $60 $50 $40 $30 Expenses $20 $10 Used moneylender Used savings club payout Converted using $1 = 6.5 South African rand. Source: Collins et al. (2009), 41. $0 20-Mar 17-Apr 15-May 12-Jun 10-Jul 7-Aug 4-Sep 2-Oct 30-Oct 27-Nov The human body, however, does not do so well on a diet that alternates feast and famine. The children should eat every day. The collision between volatile income and constant needs creates an intense demand for ways to set aside money on good days, or good seasons, and pull it out on bad. But the challenge is not purely financial: it also psychological and social. In theory, people should be able to handle the volatility by putting enough money under the mattress on the good days. In practice, that discipline is hard to muster. With the cash sitting right there, beer and sweets and cigarettes are harder to resist. With the cash sitting right there, family members asking for a share are harder to deny. Thus the 16 Collins et al. (2009), 40–42. 11 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 arm’s length, businesslike nature of financial services is part of their value, for they help people remove money from their homes and bind themselves to better behavior. Twice during the period graphed in Figure 2, for example, Pumza’s profits went slightly negative. The first time, she used a payout from a savings club (a ROSCA, explained in chapter 3) to tide herself over. The second time she went to the moneylender.17 Both these mechanisms helped her commit herself to setting aside money when she could while resisting temptations and relatives’ pleas. As if living with a volatile income wasn’t hard enough, what a poor family spends also tends to be more unpredictable, above all because of illness. Most poor people lack health insurance; yet disability and death are more frequent visitors at their doorsteps.18 Again summarizing household surveys from many countries, Banerjee and Duflo found that, depending on the country, 11–46 percent of households below a dollar a day had someone who had been bedridden or had needed a doctor within the last month.19 Together, the loss of income when a breadwinner takes sick and the cost of pills and doctors can undo years of assiduous saving and asset-building, plunging a family into destitution. One day in 1989, recounts Portfolios of the Poor, a Bangladeshi rickshaw driver named Salil came home to his wife, complaining of a sore throat. He consulted a series of doctors. To pay them, he sold off his three rickshaws one by one, the capital of his livelihood. The doctors did not help. Salil ended up going to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with throat cancer and died within days. Through the whole period, bereft of income, his wife had borrowed to support the couple and their three small children. “His widow and family were left without a breadwinner, without assets, and saddled with debts.” They became the poorest Bangladeshi household in the financial diaries studies.20 They did not have health and life insurance like me. If Salil’s story is unusual, it is so only in degree, not kind. Fifty percent of the Bang17 Ibid. On income volatility, see Morduch (1995). 19 Banerjee and Duflo (2007), 149. The poverty line is $1 of household spending per member per day, converted to local currency using purchasing power parities. 20 Collins et al. (2009), 86–87. 18 12 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 ladeshi financial diary households experienced illness during the yearlong study period, as did 42% of Indian ones. Fully 81% of the households in South Africa, where AIDS is common, experienced the financial emergency of a funeral.21 The exaggerated myth of microentreprise One common strategy for managing risk on the income side of the ledger is diversification. A survey of 27 villages in West Bengal, India, found that households typically had three workers, who among them practiced seven occupations.22 Banerjee and Duflo found that a fifth of urban households in Peru living on less than $2 a day per person earn from more than one source, as do a quarter in Mexico, a third in Pakistan, and half in Côte d’Ivoire.23 In the extremely poor district of Udaipur in the Indian state of Rajasthan, almost everyone owns and farms some land, but 74 percent of those with incomes below a dollar a day earn most of that income in day labor—working for others without the security of long-term employment.24 Naturally, people with multiple income sources are not juggling multiple jobs. Rather, selfemployment is common—more so than among the rich. It was reported among a quarter of poor and rural households in Guatemala and a third in Indonesia and Pakistan.25 Banerjee and Duflo explain the attraction of working for oneself: If you have few skills and little capital, and especially if you are a woman, being an entrepreneur is often easier than finding an employer with a job to offer. You buy some fruits and vegetables or some plastic toys at the wholesalers and start selling them on the street; you make some extra dosa [rice and bean pancake] mix and sell the dosas in front of your house; you collect cow dung and dry it to sell it as a fuel; you attend to one cow and collect the milk. These types of activities are exactly those in which the poor are involved.26 21 Ibid., 68. Banerjee and Duflo (2007), 152. “Typical” figures are medians. 23 Idem (2007), 152. 24 Ibid., 151. 25 Ibid., 152. 26 Ibid., 162. 22 13 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 Self-employment, then, is one response to being poor in a poor country. But thanks to the promotion of microcredit, it has become something much more in the public imagination. It has become microenterprise: not just a response, but a solution; and not just one reason the poor want financial services but the reason. It is true that the global poor, more than the global rich, must fend for themselves economically. So the image of the poor as microentrepreneurs is not pure mythology. But overall, they, like everyone else, use a variety of financial services for a variety of purposes. As a result, arrangement through which rich investors finance microcredit tend to become chains along which funds travel—while perception and reality collide.27 A user of Kiva, the on-line peer-topeer microcredit site, might lend money to one of the “entrepreneurs” listed on the website. The funds would go to Kiva, then to a local microcreditor, then to a borrower rather like the one pictured on the site.28 That borrower might use the credit for microenterprise…or might not. The more a fundraiser like Kiva exaggerates the role of microenterprise in order to raise funds, such as by calling all clients “entrepreneurs,” and the more that microfinance institutions describe themselves as supporting the same, the more that point of collision is pushed toward the client. What clients really do with the credit, which is elusive under the best of circumstances, falls further below the radar of the investor and the intermediaries. When asked how they use a service, microfinance clients often give the answer they believe is wanted. They respond this way out of ordinary self-interest; to ignore self-interest is a luxury the poor cannot easily afford. In Bangladesh, a borrower’s husband told anthropologist Lamia Karim with a smile that “We took a cow loan. Fifty percent will be spent to pay off old debts, and another fifty percent will be invested in moneylending. If the manager comes to see our cow, we can easily borrow one from the neighbors.”29 Sometimes the obfuscation is more subtle, and even unconscious. This is because what a Recall from chapter 1 that by “investor,” I mean all those who finance microfinance, whether through gifts, loans, or equity investment. 28 Borrowers pictured on Kiva 29 Karim (2008), 16. 27 14 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 person appears to use a loan or savings drawdown for can and what it enables her to do are two different things. Beatrice, the female half of an entrepreneurial couple in Zambia’s Copperbelt, explained to British researcher James Copestake that, in his words, “the main difference the loans had made over the last year was in freeing their own capital for construction of their house.” Microcredit loans formally went into the business, but only by supplanting the couple’s own capital into personal uses.30 So in fact the microcredit went for home improvement. The Malaysian journalist Helen Todd succeeded better than most in piercing this fog, giving us a rare statistical view of what one service, microcredit, actually allowed poor people to do. Throughout 1992, she and her husband David Gibbons, who was also studying microfinance, lived amid two villages in the Tangail district of Bangladesh, one of the first regions in which the Grameen credit program operated on a large scale. With a research team that included Bangladeshis, they tracked the financial and personal lives of 62 women, 40 of whom borrowed from Grameen, in a way that foreshadowed the financial diaries. Todd and her team complemented their quantitative data with “qualitative” evidence— hundreds of conversations and observations over the course of a year. Table 2 shows their tabulation of how the 40 borrowers said they would use the credit, in order to obtain loan approval, and how they actually used it. All the stated purposes were investments. “According to the [Grameen] Bank records,” Todd writes, 35 of our 40 member sample took loans in 1991/92 for either “[rice] paddy husking” alone or “paddy husking/cow fattening.” As far as we could tell, only four women did any paddy husking for sale during the year and that only for limited periods. Two young women who lived in the same bari [or homestead lot] had taken their last few loans for “cow fattening.” Although I was in and out of their bari for seven months of the year, I never saw hide nor hair of any cows.31 As expected in light of the data from Banerjee and Duflo, Todd’s data in Table 2 do not entirely debunk the image of poor women as microentrepreneurs. Four women really did appear to take loans for 30 31 Copestake (2002), 746. Todd (1996), 25. 15 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 cows, and another two invested in equipment or stock for back-breaking work of grinding mustard seeds for oil. Three more bought rickshaws, presumably for their husbands to use as a source of income. But clearly more was going on. Some women used the loans to pay dowry, breaking a vow they took as Grameen members.32 Others bought rice. Some improved the roof or walls of their small homes. In fact a majority did use the credit for what can be considered business activities, though not ones usually thought of as microenterprise: moneylending and the leasing or buying of rice land. Bank policy proscribed land leasing in particular, viewing the rents as usury extracted by landlords, a perspective which reflects the history intertwining of moneylending and land monopoly. But for many families, leasing land was a step up in security and freedom: instead of working someone else’s land for a daily wage set by someone else, the husband could plant and manage the family’s “own” field. Once during the research project, Grameen Bank founder Muhammad Yunus visited Todd and Gibbons, who briefed him on their findings. They urged him to allow land leasing: Dr Yunus listened but did not commit himself. “Let’s go to the village,” he said. … Professor Yunus questioned Kia [a borrower] about [a new] loan. “Do you want one?” “Yes, sir!” “What will you use it for?” I saw Kia hesitate for a moment. Then she looked the Managing Director in the eye. “I won’t lie to you,” she said. “I am going to lease in some land.”33 In that moment, Yunus’s notion of how the poor ought to use credit collided with the notions of the poor themselves—somewhat ironically, given his expressed faith in the ability of the poor to find their own way with the help of credit. 32 The custom of paying dowry makes girls economically burdensome and boys lucrative, reinforcing discrimination against girls within families. 33 Ibid., 16–17. 16 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 Table 2. Approved and actual use of Grameen Bank loans to 40 women, 1992 2 Number of loans 1 Approved Actual 20 8 7 4 4 2 1 1 20 16 12 7 3 2 1 Amount of loans (taka ) Approved Actual Rice paddy husking 73,500 Rice husking/cow 46,000 Cow 42,500 19,300 Mustard oil grinding 23,000 5,760 Grocery trade 5,000 Mustard oil/sweets 5,500 Land transactions 70,320 Loan repayment 24,720 Stocking rice 27,134 Lending 6,849 Rickshaw 6,137 Dowry/wedding 5,075 Housing materials 4,680 Other/unknown 25,025 1 2 Loans put to more than one use listed more than once. $1 = 40 taka . Source: Todd (1996), 24. This kind of mythologizing is also embedded labels applied to people who work for themselves as a matter of survival. In the 18th and 19th centuries in the British Isles, such people were “industrious tradesmen.”34 Some on the Continent some saw them through the lens of the labor-capital divide—as workers who could become small capitalists.35 Today, rickshaws drivers and mustard grinders are often said to be running “microbusinesses.” They are “microentrepreneurs.” These fusions of a silicon-era prefix with a capitalist projection appear to have originated with a volunteer for Acción International named Bruce Tippett in 1974, not long after “microprocessor” entered the language.36 “Microentrepreneur” is apt in important respects, for the people so labeled risk their tiny bits of capital, work for themselves, and reap the profits and loss of their operations. But unlike the prototypical rich-world entrepreneur, few “microentrepreneurs” draw in new investors, innovate, expand, or create jobs. They do not abandon steady employment in order to launch themselves into bold ventures. Rather, they are quite conservative in investing in themselves. Evidently, 34 E.g., Piesse (1841), 9. E.g., Wolff (1996), 2, 10, 16, 19. 36 Jeffrey Ashe, Director of Community Finance, Oxfam America, Boston, MA, interview with author, November 26, 2008. 35 17 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 living on the edge curtails one’s appetite for risk. An experiment in Sri Lanka showed that injecting modest additional capital into microenterprises let the owners earn average returns of 5 percent per month (about 60 percent per year), far higher than what most major corporations earn.37 The same experiment in Mexico generated returns exceeding 20–33 percent per month.38 Presumably, the law of diminishing returns would set if these microenterprises grew to become less “micro.” Why poor people don’t push farther toward the point of diminishing returns, why they leave these winnings on the table, is not fully clear. They may not recognize the opportunities to sew more saris or better stock their shelves. They may struggle to pull together the lump sums needed to invest. Perhaps microbusinesses are like tech stocks—high return on average but also high risk—and to reduce risk, people spread their eggs among many baskets. Whatever the cause, poor entrepreneurs are apparently less venturesome than they could be. All in all, they are not the agents of creative destruction whom economist Joseph Schumpeter saw as the heroes of economic development. They undertake—to revert to the root meaning of “entrepreneur”—mainly to survive.39 To this extent, labeling them “microentrepreneurs” romanticizes their plight and implies too much hope for their escape. A somewhat older and now less fashionable view of poor entrepreneurs, historically associated with the International Labor Organization, is as victims of economic systems that fail to provide enough jobs. To put this more constructively, since the Industrial Revolution, explosive job creation has powered all national economic development successes. Comprehensive economic development is hard to imagine without jobs. In this view, the people of whom we speak have not benefited from such devel- 37 de Mel, McKenzie, and Woodruff (2008a). McKenzie and Woodruff (2008). Other studies have found similar conservatism among poor farmers in deciding, for example, whether to apply commercial fertilizer. See Morduch (1995), 105. 39 de Mel, McKenzie, and Woodruff (2008b). 38 18 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 opment. They are “people without jobs” or “self-employed” or “own-account workers” who heroically, but tenuously, survive their circumstances.40 We do not need to choose between seeing the poor as victims or masters of their own fates, as microentrepreneurs or people without jobs, for there is truth in both views. One’s economic possibilities are very much defined by economic circumstances beyond one’s control. Given those circumstances, financial services can help people manage better. Microfinance may not reliably help people climb out of poverty, but it can help them manage it better, in part, indeed, through microenterprise. How the poor use financial services Having disenthroned one common but narrow view of how poor people use financial services, it remains for us to forge or find or a more realistic view. Perhaps no one is a better interpreter of how poor people manage money than Stuart Rutherford. A trim man with thin-rimmed glasses and a dusting of white hair, he loves nothing more than interviewing people about they handle their finances. Trained as an architect, he became interested in the subject while investigating the effects of the earthquake in Managua just before Christmas in 1972. There, as in Haiti in 2010, many slum dwellers lost their homes. Yet somehow they summoned the financial resources to rebuild rapidly, confounding many foreign aid officials. In his 2000 book, The Poor and Their Money, Rutherford focuses less than I have on the purposes for which the poor use financial services, and more on the transactions involved. At base, he argues, poor people need financial services in order to turn small, regular savings into “usefully large sums.” These sums can go toward three of the four purposes I discovered in my inventory: investment, gaining ownership of assets, and managing consumption.41 The last, as we have seen, is essential. As one poor Bangladeshi told Rutherford, “I don’t really like having to deal with other people over money, but if you’re poor, 40 41 ILO (1993), §§7, 10.3. Rutherford (2000), 1. 19 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 there’s no alternative. We have to do it to survive.”42 Rutherford emphasizes how three specific types of financial service—loans, savings, and insurance—all help people with the core task of assembling large sums. Through all of these services, people can make small, regular payments—loan service, savings deposits, insurance premiums—and take occasional large pay-outs. As a matter of money flow, the services differ only in timing of the ins and outs. Borrowing and saving, in particular, are not nearly so opposite as they appear. Rutherford illustrates their similarity with two examples he and his research partner Sukhwinder Singh Arora found in the slums of Vijayawada, a city in southeastern India. The first example is of savings: Jyothi is a middle-aged semi-educated woman who makes her living as a peripatetic (wandering) deposit collector. Her clients are slum dwellers, mostly women. Jyothi has, over the years, built a good reputation as a safe pair of hands that can be trusted to take care of the savings of her clients. This is how she works. She gives each of her clients a simple card, divided into 220 cells….In each cell, clients commit themselves to saving a certain amount in a certain period. For example, one client may agree to save five Indian rupees (Rs 5) [about 10¢] per cell at the rate of one cell a day….Having made this agreement it is now Jyothi’s duty to visit this client each day to collect the five rupees… When the contract is fulfilled—that is when the client has saved Rs 5, 220 times…the client takes her savings back. However, she does not get it all back, since Jyothi has to be paid for the service she provides. These fees vary, but in Jyothi’s case it is 20 out of the 220 cells—or Rs 100 out of the Rs 1,100 saved by the client in our example.43 Notice that Jyothi does not pay interest on deposits as conventional banks generally do; she charges—at a rate that works out to 30 percent a year.44 Rutherford asked Jyothi’s clients why they pay so much to save when stashing cash in a box is free: The first client I talked to…knew she would need about Rs 800 in early July, or miss out on admitting her children to school. Her husband, a day labourer, could not be relied on to come up with so much money at one time, and in any case he felt that looking after the children’s education was her duty, not his. She knew she would not be able to save so large an amount at home—with so many more immediate demands on the scarce cash. I asked her if she understood that she was paying 30 per cent a year….She said that she did, and still thought it a good bargain….[D]wellers in a neighbouring slum where there is no Jyothi at work actually envied Jyothi’s clients.45 42 Collins et al. (2009), 13. Ibid., 13–14. 44 As discussed below, steady repayments over the loan period make the average balance half the starting balance and approximately double the effective interest rate. 45 Ibid., 15–16. 43 20 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 Bankers call Jyothi’s service a “commitment savings account.” By removing a bit of money from the house each today, Jyothi protects her clients from pressures to spend too much now. Jyothi facilitates thrift. Paradoxically, commitment savings ties the clients’ hands in a way that strengthens their control over money and power in the family. Poor people do have other ways to save, such as in jewelry and livestock. But thieves can take rings and pigs can die. And such assets are inconvenient: as one Indonesian pointed out, “when you have to pay the school fees, you cannot sell the cow’s leg.”46 In India, Rutherford also talked to clients of a moneylender, whose …working method is simple. He gives loans to poor people without any security (or “collateral”), and then takes back his money in regular instalments over the next few weeks or months. He charges for the service by deducting a percentage (in his case 15 per cent) of the value of the loan at the time of disbursal. One of his clients reported the deal to me as follows. “I run a very small shop” (it’s a small timber box on stilts on the sidewalk inside which he squats and sells a few basic household goods) “and I need the moneylender to help me maintain my stock of goods. I borrow Rs 1,000 from him from which he deducts Rs 150 as interest. He then visits me weekly and I repay the Rs 1,000 over ten weeks….As soon as I have paid him off he normally lets me have another loan.” This client (Ramalu) showed me the scruffy bit of card that the moneylender had given him and one which his weekly repayments are recorded. It was quite like the cards Jyothi hands out.47 The similarities to Jyothi’s commitment savings service are striking. The moneylender too uses grids printed on cards to track payments. Both the savings and credit services operate cyclically, producing the same predictable rhythm of frequent, small pay-ins and infrequent, large pay-outs. Perhaps most importantly, both provide discipline. They help people set aside money each day or week and resist what must be strong temptations to spend or hand over it all. The financial services do this by both reminding and binding. This distinction might surprise. Is not discipline synonymous with compulsion? Not quite. A study in Bolivia, Peru, and the Philippines found that people with voluntary savings accounts saved 6% more on average if they received regular text message reminders to save.48 Evidently, the reminders helped them summon self-discipline. And evidently, part of the value of a loan 46 Robinson (2002), 264. Rutherford (2000), 17–18. 48 Karlan et al. (2010), 39. 47 21 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 repayment schedule, binding as it is, lies simply in regularly drawing clients’ attention to the priority of setting money aside. Here too we see financial services meeting a need that the rich also experience, if less intensely than the poor. Discipline is more difficult where money is tighter and life is less predictable. A study in Hyderabad, India, found that offering microcredit reduced household spending on “temptation goods” such as tea and cigarettes, and increased spending on durable goods such as sewing machines.49 In the slums of Nairobi, researchers Siwan Anderson and Jean-Marie Baland found that 84 percent of participants in local savings clubs known as ROSCAs were women.50 And among women, the ones most likely to join were neither those earning all the household’s income nor none of it, but those in between. Roughly speaking, sole breadwinners did not need the leverage (with respect to husbands) of a commitment savings arrangement; non-breadwinners had no income to leverage. And evidently, women needed the leverage with respect to their spouses more than men. In their paper, “Tying Odysseus to the Mast,” economists Nava Ashraf, Dean Karlan, and Wesley Yin discovered the same need in the southern Philippine island of Mindanao. Working through a rural bank, they offered a new commitment savings account to randomly picked customers. Interestingly, even though the commitment account locked up clients’ money, it did not pay a higher interest rate than the bank’s ordinary savings account. Yet 28 percent of customers who got the offer took it. After one year, those offered had saved 81 percent more than those not. Women in whom psychological tests revealed a strong tension between how they manage money in the moment and how they wish they could over the long term were more likely to join than 49 Banerjee et el. (2009), [xx]. Anderson and Baland (2002). The rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCA) is the most prevalent form of informal financial service. See chapter 3. 50 22 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 other women, and more than men in general.51 Evidently some of them recognized their need for external discipline. To the extent that financial services resemble one another, they can substitute for one another. One woman might save to buffer her family against the possibility of a husband taking sick. Another might avail herself of rudimentary health insurance such as that offered by the group SHARE Microfin in India.52 Another might borrow to pay clinic fees when needed. A survey in the Indian state of Karnataka found that 40 percent of households included someone who had suffered an expensive health problem in the last year. 67 percent of these tapped savings to help pay the bills and 44 percent borrowed. 53 But this is not to suggest that poor people could happily switch between savings, credit, and insurance. These types of financial services are neither perfect substitutes for each other nor freely substitutable. In Karnataka, only 0.3 percent of the households with health troubles drew on insurance, which is not surprising since almost none could buy any. Few could swap in this superior service to replace savings or credit. By and large, the poor must self-insure. And the intuition that credit and savings are deeply different does contain truth. Fundamentally, they impose different risks on clients. With savings (and insurance) the client runs the risk that the financial institution will collapse or steal her funds. Hyperinflation can effectively do the same thing. With credit, the danger is that bad luck or bad judgment will lead the borrower into repayment difficulties. Then the temptation will be to borrow even more—to take new loans to pay old ones. Whatever mechanisms the lender uses to enforce collection—public shaming, peer pressure, the proverbial damage to kneecaps—then come to bear. 51 The average effect reported here is for those receiving the offer, not those taking it. The group receiving the offer is randomly defined, and is the basis for meaningful comparisons. People in the subgroup taking the offer are self-selected and might have saved more anyway. “Tension” refers to the time consistency, or hyperbolic discounting, the researchers found. Asked to choose between hypothetically receiving 200 pesos today or 300 a month later, and then between 200 in 6 months or 300 seven months from now, those women offering conflicting answers—200 when the choice was today, 300 when it was deferred—were more likely to join than other women, and than men generally. 52 sharemicrofin.com/services.html, viewed October 20, 2010. The insurance is underwritten by the U.S. group MicroEnsure. 53 Duflo et al. (2008). “Expensive” means costing more than 300 rupees. The average reported cost for such episodes was Rs 1,900, which is more than twice the average per-capita consumption in the sample, Rs 708. 23 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 The differences in risk show up as differences in cost. Financial service providers are generally seen as better risks than individual clients. That means that you must pay more to your bank for trusting you (in lending to you) than you must pay when trusting the bank (in saving with it). In Vijayawada, for instance, despite the modest appearance of the 15 percent up-front charge, Ramalu’s moneylender charges far more than Jyothi does for taking savings. After subtracting the Rs 150 fee, Ramalu’s initial balance is Rs 850. He starts repaying immediately so that his average balance over the 10 weeks is half the Rs 850, or Rs 425, of which the Rs 150 is 35 percent. A rate of 35 percent for 10 weeks works out to 182 percent per year and a stunning 382 percent with compounding, more than ten times Jyothi’s rate. Why then has the microfinance been led and dominated by one service, and an expensive one at that, namely microcredit? One reason is that regulators are more willing to let start-up non-profit groups place funds with the poor than vice versa. Only institutions meeting certain standards—banks—should be entrusted with other people’s money. This is a good reason. But notice that it does not imply that credit is ideally better for the poor than savings and insurance. Thus, various financial services can substitute for one another, in practice they do so partially and imperfectly. That means that poor people often use financial services in ways that are not ideal. That a loan is taken in practice does not mean that a loan is best in principle. Conclusion This review of the role of financial services in daily life and economic development generates a series of cautions for those who see microfinance—microcredit in particular—as an eliminator of poverty. The poor need financial services for many things in addition to enterprise. Credit can serve many needs, but savings and insurance serve many needs more effectively when available. Microentrerprise is more about surviving poverty than escaping it. Thomas Dichter, a long-time practitioner and evaluator of microfinance, observes that no country that is rich today got that way through tiny loans for tiny enterpris- 24 Roodman microfinance book. Chapter 2. DRAFT. Not for citation. 3/22/2016 es.54 Indeed, every comparison between rich and poor countries, as between poor and middle-class people within poor countries, drives us to conclusion that in the broad, economic development is synonymous with reduction in microenterprise and growth in employment due largely to the expansion of formal enterprises backed by more conventional finance. All this suggests that next to the extraordinary poverty-reducing power of the industrial revolution, microfinance is a palliative. Does that mean that the value of microfinance is sometimes exaggerated? Probably. Does that make it wasted charity? Not necessarily. The poor need financial services at least as much as the rich. For people navigating the unpredictable and unforgiving terrain of poverty, any additional room for maneuver, any additional control, can be extremely valuable. As Jonathan Morduch, a New York University economist and thoughtful observer of microfinance, told a writer for the New Yorker, “That is a valid critique, to a point. But get real. How long are you willing to wait for the revolution? I can’t see any moral foundation for not trying to address the current deprivations of the world’s poorest billions. If microfinance can help provide options in cost-effective ways, we should celebrate it.”55 54 55 Dichter (2007). Bruck (2006). 25