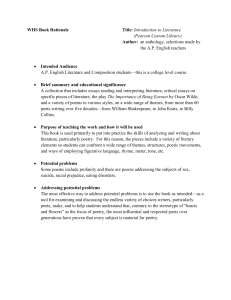

Advanced Placement Literature and Composition • Gregg Painter

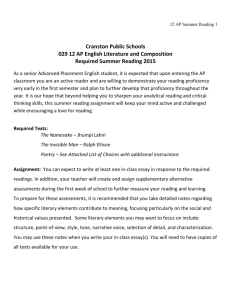

• Advanced Placement Literature and Composition

• Gregg Painter

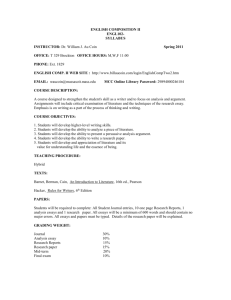

This course appears at first glance to be a “test prep” class, but given the nature of the test, that’s not a bad thing. The AP literature exam, given in May, is a rigorous test of a student’s ability to read a text closely and write about it cogently. These skills are in keeping with the spirit of any literature class, of course, but the level at which students are expected to perform is significantly higher. Aside from the usual reading, writing and discussion (more of which revolves around poetry than most high school courses), the curriculum includes the study of terms and methods used in the analysis of literature.

It is a college level course, and students are expected to speak up in our discussions as if they were taking a seminar course.

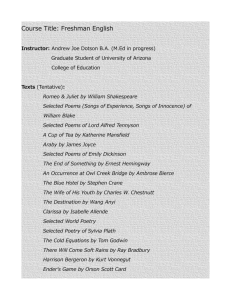

Novels and Plays

If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler … (Calvino)

Song of Solomon (Morrison)

Crime and Punishment (Dostoyevsky)

Beowulf

Grendel (Gardner)

Macbeth

Book costs : This upcoming 2013-14 year, we have about 100 students, so more than half of you will have to purchase your own novels. The total cost might range from $25 to $80, depending on whether you buy them new or used. Macbeth you do not need to buy. The Calvino novel we may or may not get to at the end of the year. Song of Solomon is the novel we begin with.

We have class copies of the main text (short stories and poetry) for everyone.

Take note of the summer reading assignment notification listed on the AP section of DSA’s site. Email me with any questions. Following are a few procedures and then a detailed syllabus, which is always altered as the year goes by!

Homework

Most of the homework will be of two types: reading novels and finishing written work begun in class.

Reading schedules will be given for each novel, and posted on my website.

Grades

Grades are based primarily on written work, including tests, and secondarily on class participation. Check on your students’ grade through Infinite Portal or email me with questions. First and second quarters are graded separately and then averaged in with their final.

Tests

May be given at any time over the assigned material.

Other info:

Make-up work

Work from excused absences must be made up within one week after return to class for full credit. It is the student’s responsibility to obtain the work.

Late work

Work turned in a day or two late may have one grade taken off. After a week, work will receive half-credit at most (50%, an F). If you are involved in a performance/show/etc. that interferes with your turning homework in on time, write an explanatory note at the top of the paper and you will receive full credit for your work. Talking to me beforehand would also be helpful.

Missing work

Turn in all your work. The computer averages in missing work as a zero.

Contacting me

E-mail is the best way to get in touch with me. From the DSA home page (http://dsa.dpsk12.org/), go to

“Academics,” then “language arts,” where you can click on my email.

What’s going on in the classroom?

You can find out what we’re currently working on by checking my web page.

Clarification on Infinite Campus automatically generated phone calls:

• Every week, IC Messenger will send notices regarding failing assignments. These are notices of assignments that earned a failing grade (less than 59%). To verify a student’s class grade, you will need to check IC in more detail. Please keep in mind the grading policies as stated in the syllabus above. IC

Messenger will also send out a message if the student has missed an assignment. Failing grades will be sent once per week, missing grades may be sent multiple times over a nine-week period.

Another aside on IC: if you see an “x” or a blank, there may be several reasons for this. It could mean that a student missed a minor discussion and is excused. It could mean the assignment is entered but has not been graded. In any case, in neither case is the student’s grade affected. An “M” or a “0” indicates a missing assignment and should be cleared up to ensure a good grade in the course.

The following pages give you an idea of the kind of work we’ll be doing in a little more detail.

The Advanced Placement Literature and Composition course at Denver School of the Arts is designed to give the students linguistic, reading and analytical tools they may not have been called upon to use fully in high school courses, skills they will be expected to have in good colleges.

These include:

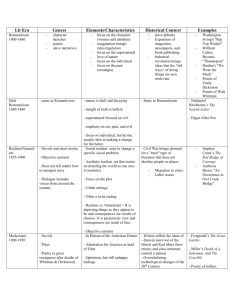

1. The ability to read more complex material, especially older British writers with their more complex syntactical structures. Although perhaps not as useful on the AP test, important and unusual modern writers are also presented to the class, as the purpose of an introductory college literature and composition class is to present students with a wide range of reading material, from the ancient Greeks to the post-modern devotees of semiotic theory.

2. The ability to write using more complex and varied syntax and diction. This I see as the core of the course, as I have seen hundreds of very bright students whose writing does not reflect their intelligence or their analytical skills, as evidenced in discussion.

I blame the red-penned RO (run-on) scolds for their deficiencies of syntactical variety. Their sentences are too often twelve to fifteen words in length. They have, by and large, not learned how to use the semicolon, which is not just a punctuation mark, but a linguistic device used to show a sophisticated relationship between similar ideas, often subordinating one observation to another larger point. Nor have they realized how powerful the short sentence can be in creating exciting prose.

The function of paragraphing is lost on many of them, and its concomitant indication of long and logical patterning of an argument. Beyond this, adding the transitional devices traditionally used at the end and beginning of paragraphs is emphasized.

Although not as vital to the speedy AP test, various means of structuring essays, such as leading up to the main thesis instead of beginning with it, developing creative and compelling introductions and conclusions, and a host of other structures which they both read and write, are introduced to them. (My professor friends despise the five-paragraph essay, so we consider that ancient history in our AP class.)

3. Despite an aversion to analysis among many of our artists (this is Denver School of the Arts, and practicing artists often rely more on The Muse than the left brain for creation of art), rigorous attention to the text at hand is required at every stage of the course. Discussion of various approaches to analysis is encouraged, including challenges to the concept of analysis itself.

Effective use of quotations embedded in sophisticated defense of original theses is something we expect every student to be able to do reflexively by the end of the year.

This is one aspect of AP Lit and Comp which distinguishes it from our typical high school literature classes, where more creative, individual, and heartfelt responses to works of literature are encouraged. (Not that we neglect emotional responses to poems and stories and novels in our AP class, nor do we neglect to view the writer primarily as an artist.)

____

The following breakdown of class content may be exact, but it serves as a template for what we cover.

Relevant short stories are mentioned, although they are subject to change based on the instructor’s whims or what is relevant and compelling in contemporary short-story collections, The New Yorker, Granta, and the usually too-strange McSweeny’s.

The poetry is not detailed below, as we read at least one hundred poems during the course, usually from our primary text (Literature, Roberts and Jacobs, Prentice-Hall) or from our secondary text (Literature:

Structure, Sound and Sense, Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovich), as well as from other contemporaneous sources.

(A section on the novels we simultaneously read follows this chronology.)

The literature we read is treated many different ways. Discussion, either as a whole class, half a class, or in small groups is indispensable and is usually paired with either a small bit of pre-discussion writing, a larger analytical piece of writing, and/or oral presentation.

We have about twenty years worth of practice tests on hand, and these are the prompts for much of the student writing we do. They are synched to our current area of study. For example, early in the year we tend to work on essays whose questions don’t call for a lot of literary terminology which we have yet to cover.

These practice essays are often paired with useful student essays (good and bad) and AP readers’ comments on the essays. The College Board material is invaluable in this regard.

Essays are read and parsed more thoroughly by the instructor than are essays in other H.S. classes, and copious comments are of course designed to individualize the program and maximize the writing and thinking growth of each student.

Creative writing is a less common though no less important component of the course. Mimetic writing, for example, often gives the student a more holistic and intuitive view of how the writer does what she does in producing her art. Less strictly analytical writing can also sometimes connect the student as a person to the work being studied.

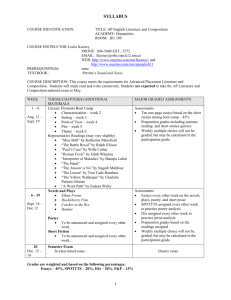

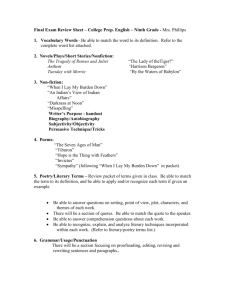

Weeks 1-2:

First Day: a practice AP Test, including an essay and a multiple-choice test, undertaken to let students know the kind of examination they will be taking in May as well as the perspective from which we will be viewing literature.

These weeks also serve as a time to contextualize the coming year’s investigation, by looking at the origins and present-day role of literature in human society. Evolutionary aesthetics (as promulgated in philosopher

Frederick Turner’s Beauty, for example) will be one of the primary focuses of this unit. Federico Garcia

Lopez’s “The Irrestible Beauty of All Things” is included here.

Primarily, we examine, as we do all year, the nature of literary analysis of the type that is expected of them on the AP test and in college in general. Reading critical analyses of works we are reading provides a good compass for them to orient their thinking in this regard.

Weeks 3-4

The Short Story. Carver’s “Neighbors” and Kincaid’s “What Have I Been Doing Lately” are read and discussed as examples of wildly different variations of the short story.

Poetry, concentrated on more in the later sections of the course but never neglected in any given two-week period, is also introduced, with plenty of student input and a plethora of divergent examples of the form.

Weeks 5-6: Plot

“The Destructors,” by Hardy

“The Japanese Quince” by Galsworthy

This is a point where student creative writing can be useful, having them develop the bare bones of a plot for a short story/novella, including conflict, character growth, etc., writing one scene from the piece in detail.

Plot in poetry is more rare outside of older epic poetry, reasons for which are discussed.

Weeks 7-8: P. O. V.

“Haircut” by Lardner. Great example of a story written from the POV of an unreliable narrator.

“Hills Like White Elephants” by Hemingway. The ultimate in third person objective POV.

Poems where the speaker is obviously not the poet are read here.

Weeks 9-10: Character

“Paul’s Case” by Cather

“Tears, Idle Tears” by Bowen

Poems primarily about characters; psychological representation in poetry.

Weeks 11-12: Setting

“The Portable Phonograph,” by Clark

“The Secret Sharer” by Conrad

Poems from the battlefield to the pasture to the attic: importance of setting in poetry.

Weeks 13-14

15-16; Tone and irony

“Rape Fantasies” by Atwood

“The Loons” by Laurence

“Hammon and the Beans” by Paredes

“The Guest” by Camus

Tone is an almost constant element of our analysis of a piece of fiction or poetry, and is consistently present in AP test questions.

As fish can hardly describe water, we have a problem with identifying irony, as it has become the psychic sea in which we swim in modern Western society, especially in the sarcastic/ironic teen culture. Irony in all its forms is also a topic we keep coming back to.

Weeks 17-18: Denotation, connotation, style, diction, syntax

“The Poor Aunt Story” by Haruki Murakami

“A &P” by Updike

Much poetry (including Graves’ “The Naked and the Nude.”)

Weeks 19-20: Imagery, symbolism, allegory, personification

Again, a lot of poetry, but it should be noted that a lot of these literary terms have already been introduced by necessity in discussions of Song of Solomon, for example.

Weeks 21-22: Figurative Language, paradox, over/understatement, metonomy, synechdoche, metaphor, allusion

More poems!

Weeks 25-26; Prosody: Meter, rhyme and sound, especially in poetry. Although this aspect of poetry is not the crucial aspect of study it was a hundred years ago (especially the ability to name metrical forms), it is still a vital topic to visit. Of special concern – and this really applies to all the literary devices we learn – is the ability to connect discussion of the device to the central intent/theme of the poem/poet.

Weeks 27-28: Form and pattern.

At about this juncture, they are given a brief encyclopedia of literary terms and are tested on them. These terms constitute the main “content” in terms of specific elements of knowledge to be studied. Directing students to be able to stick to the text and control their own prose in doing so – including their use of transitions, parallel construction, compelling work choice, appropriate structure, etc. – remains the backbone of this course.

Weeks 29-30: Test prep and whatever else we may have missed!

Various strategies to maximize one’s score on the AP test are examined.

Weeks 31-36: Depending on the calendar, all or part of Goethe’s Faust is read. (A work of dubious use for the AP Lit test.) Also of little use for the test, but possibly useful as a preview of what they may encounter in college, we undergo a closer examination of various literary schools that have sprung up like mushrooms

(or toadstools, depending on your point of view) in the latter half of the twentieth century. More gradschool criticism is read here.

Novels:

Again, simultaneous with the units detailed above, students will be reading novels on their own time.

Activities related to these novels will be undertaken within and without the walls of the classroom.

If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler… Italo Calvino

A post-modern novel, a novel about the act of reading, admittedly a quirky way to start the year. But it gets students thinking about the act of reading, and introduces them, tangentially, to meta-analysis, which is one way of approaching what it’s like to be in a college literature course.

Song of Solomon Toni Morrison

Kids usually enjoy this one, and it is almost always of use on the AP Lit test’s Open Question. We end this novel with two activities. First, a creative response to the book, ranging from paintings to interpretive dance. Second, an examination of several essays published on the book. (Allen, Dixon, Falore, others.)

Students read these essays and report back to the class on them, that way establishing an idea of how many ways a book can be read without spending the time it would take to read all of the material written on Song of Solomon.

Beowulf author unknown

Hey, everyone’s got to read this sometime in their life! (Is there a grammatical problem with the use of

“their” here instead of the more proper “his or her?” Well, that is one more thing that can come up in class: the changing nature of language and the prescriptivist/descriptivist gap in linguistic theory and practice.)

Grendel John Gardner

Another student favorite. We read three chapters a week. Lots of discussion about Gardner’s shifting stylistic devices and the many philosophical, sociological, psychological and theological ideas contained in the book.

Macbeth William Shakespeare (or the Earl of Oxford, Edward deVere?)

Mostly read aloud and parsed in class.

We view and discuss the Polanski film.

We read several post-grad essays on the play, one of which calls into question the whole premise of the evil king and his even more ruthless wife as villains. This essay’s premise is that “tanistry,” as it was practiced in Scotland at the time, precluded direct hereditary lineage as the primary method for assigning kingship

(positing that Duncan’s naming of Malcolm as his successor was contrary to law/custom), so that Macbeth was in effect performing his duty in killing Macbeth. Students are then asked to re-evaluate the play in terms of this article and look for textual evidence contradicting this premise.

Crime and Punishment

We begin by researching Russia in the 1860’s, the history or the czars, socialism, conditions in St.

Petersburg, and various philosophies including nihilism and existentialism (admittedly not officially designated as such at the time!), some of which we already acknowledged in our discussion of Grendel.

We end by writing a research paper on the book, using traditional MLA annotation, requiring a thesis, argument supported by academic research, etc.

“One-offs”

Many assignments are given to break the routine and stimulate student thought.

Some examples:

- Examination of poems by Paz, Neruda, and the early Surrealists that are resistant to ordinary analysis.

- Reading Patricia Highsmith’s short story with its audacious ending and its thesis in the title: “The Trouble with Mrs. Blynn, The Trouble with the World.”

- Reading sui generis prose, such as Donald Barthelme or Ben Marcus.

- Using techniques of literary analysis to unpack implications about man’s role in the universe in Erroll

Morris’ non-fiction film, “Fast, Cheap and Out of Control.”

- Taking a look at parody and satire, old and new.

- Doing timed writing assignments, such as being given ten minutes to summarize Raskolnikov’s published essay on the criminal mind.

- Peer editing.

- Typing up, copying and distributing student work back to them.

• Advanced Placement Literature

• Gregg Painter

This course appears at first glance to be a “test prep” class, but given the nature of the test, that’s not a bad thing. The AP literature exam, given in May, is a rigorous test of a student’s ability to read a text closely and write about it cogently. These skills are in keeping with the spirit of any literature class, of course, but the level at which students are expected to perform is significantly higher. Aside from the usual reading, writing and discussion (more of which revolves around poetry than most high school courses), the curriculum includes the study of terms and methods used in the analysis of literature.

It is a college level course, and students are expected to speak up in our discussions as if they were taking a seminar course.

Novels and Plays

If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler… (Calvino)

Song of Solomon (Morrison)

Crime and Punishment (Dostoyevsky)

Beowulf

Grendel (Gardner)

Macbeth

Homework

Most of the homework will be of two types: reading novels and finishing written work begun in class.

Reading schedules will be given for each novel, and posted on my website.

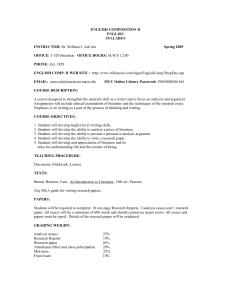

Grades

Grades are based primarily on written work, including tests, and secondarily on class participation. Check on your students’ grade through Infinite Portal or email me with questions. First and second quarters are graded separately and then averaged in with their final.

Tests

May be given at any time over the assigned material.

Other info:

Make-up work

Continued on other side

Work from excused absences must be made up within one week after return to class for full credit. It is the student’s responsibility to obtain the work.

Late work

Work turned in a day or two late may have one grade taken off. After a week, work will receive half-credit at most (50%, an F). If you are involved in a performance/show/etc. that interferes with your turning homework in on time, write an explanatory note at the top of the paper and you will receive full credit for your work. Talking to me beforehand would also be helpful.

Missing work

Turn in all your work. The computer averages in missing work as a zero.

Contacting me

E-mail is the best way to get in touch with me. From the DSA home page (http://dsa.dpsk12.org/), go to

“Academics,” then “language arts,” where you can click on my email..

What’s going on in the classroom?

You can find out what we’re currently working on by checking my web page.

Clarification on Infinite Campus automatically generated phone calls:

• Every week, IC Messenger will send notices regarding failing assignments. These are notices of assignments that earned a failing grade (less than 59%). To verify a student’s class grade, you will need to check IC in more detail. Please keep in mind the grading policies as stated in the syllabus above. IC

Messenger will also send out a message if the student has missed an assignment. Failing grades will be sent once per week, missing grades may be sent multiple times over a nine-week period.

Another aside on IC: if you see an “x” or a blank, there may be several reasons for this. It could mean that a student missed a minor discussion and is excused. It could mean the assignment is entered but has not been graded. In any case, in neither case is the student’s grade affected. An “M” indicates a missing assignment and should be cleared up to ensure a good grade in the course.