Defendant

advertisement

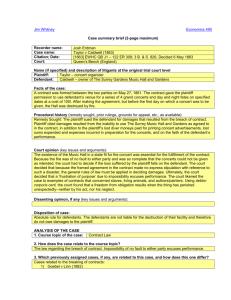

Crosby 1 Defense Team, Mock Trial 2, Cassie Crosby Foreman (p) v. R and L Builders (d), 1995 The defendant, R and L Builders, responds to the plaintiff Foreman’s suit for damages in a breach of contract by not admitting breach but, in the case breach is decided by the court, contesting the amount of damages to be recovered. The plaintiff homeowner hired the defendant to build a swimming pool and surrounding building in his backyard. The contract between the two stipulated both a cost of $100,000 and the pool’s maximum depth of 7 feet 6 inches. After construction, the maximum depth actually measured 6 feet 9 inches, with the diving area a safe 6-foot depth. The new depth has not decreased the value of the pool, and the only way to deliver the plaintiff his specific, and less efficient, 7 feet 6 inches depth is to demolish and reconstruct the entire project for an additional $33,000. The plaintiff will not build a new pool with his own money. The total loss of amenity to the plaintiff, resulting from the shallower depth, is $4,000. On behalf of the defendant, counsel requests that the court find R and L Builders only responsible for $4,000 in reliance damages if contract breach if sufficiently proven. The defendant did not necessarily breach contract in not fulfilling the maximum pool depth of 7 feet 6 inches. Friedman cites that contracts’ “objective is economic efficiency,” and the plaintiff can here realize his relative savings on pool cleaning and water costs from the shallower pool. Also, in that the actual pool depth differs by less than a foot, and the diving area is well within safety regulations, the defendant can be seen to maximize earning potential – they did not waste time and money building a deeper pool with little added benefit. The defendant may have built the pool as such for many reasons – time constraints, price changes, or unforeseen events come to mind. Regardless, Friedman states “contracts worth fulfilling will be fulfilled,” making not fulfilling a contract efficient if the benefit of breach outweighs the cost of breach. The benefit for Crosby 2 the defendant was not building an unnecessarily-deep pool, and the benefit for the plaintiff can be seen in lower maintenance costs. The issue of breach is difficult to define, in that Pareto improvements may result and thus make breach efficient. The court can see in Morin Building Co. v. Baystone Construction, Inc. (1983) that satisfaction for work done depends on whether “a reasonable person… should have been satisfied with the materials and workmanship.” Given that the pool differed so slightly from the original contract, not detracting from its value while saving R and L the added time and effort, a reasonable person can be argued to be satisfied with this pool. It is functional, safe, and within a working enclosure. In fact, the plaintiff is reasonably satisfied to the point of having no intention of rebuilding the pool with his own money. The defendant therefore fulfilled the contract competently, saving money while placing the plaintiff in a reasonable equilibrium. There is also no evidence of ill intent or willful breach on behalf of the defendant, making breach even more unlikely. The dissenting opinion of Groves v. John Wunder Co. (1939) shows willfulness’ lack of importance, breach or not, in stating the measure of damages “is the same whatever the cause of the breach… mistake, accident… or malicious [intent].” The reason why the pool was not built to the specified depth has no bearing on the damages calculated, but we do not purport a breach because of the final pool’s increased efficiency and functionality. If a breach is decided to have occurred, damages can restore the plaintiff to a reasonable measure of well-being as compared to his current state. These damages, however, should only cover the plaintiff’s $4,000 loss in amenity. This amount is based on: the lack of intention of building a replacement pool otherwise; the negligent loss of property value from the altered depth, as the pool is still safe; and the disproportionate reconstruction expenditure as compared to loss of amenity amount, which would result in economic waste if damages were to Crosby 3 include demolition and reconstruction. If the plaintiff received the specific performance damages of $33,000, or mandatory fulfillment of contract, precedents of economic inefficiency and promisees taking advantage of promisors would be set. Granting specific performance damages could incite frivolous lawsuits and increased litigation costs from otherwise-satisfied promisees. The plaintiff’s lack of intention to rebuild the pool without the defendant’s compulsory action speaks to $4,000 as the maximum amount of damages. The purpose of damages, as seen in Hawkins v. McGee (1929), is “to put the plaintiff in as good a position as he would have been in had the defendant kept his contract.” The court should note that this does not include “what the plaintiff has given the defendant or otherwise expended,” thereby ruling out damages of $100,000 for construction. Given, however, that the plaintiff does not want to build another pool without being handed the money to do so, “the only losses… are such as the parties must have had in mind when the contract was made.” What the plaintiff had in mind differs from the built pool by only 9 inches, measuring $4,000 in emotional damage. Hawkins’ award of expectation damages differs from this case with health and welfare factors, while the plaintiff’s pool is functional and safe, and he will not seek renovation from another source. The pool’s economic value and use is unchanged, compared to Hawkins’ useless hand. Damages awarded here should cover only the mental difference of what was expected and what was produced, or the plaintiff's inconvenience, because of his apathy towards the original contract’s specific, inefficient terms. Damages of $4,000 rather than $33,000 also escape the trap of putting the plaintiff in a better position than he would have been had the contract been fulfilled. The reconstruction of the pool is likely to result in a more exact and well-constructed building, but for the same price – the defendant will essentially have built the same structure twice, delivering a result worth much more than the original price. Hawkins dictates the damage amount as “the difference between the Crosby 4 [expected] value of the goods… and the actual,” and the pool’s value, from the case facts, has not changed with this depth change. In Groves v. John Wunder Co. (1939), damages are similarly defined as “limited to the loss… suffered by… the breach,” and the plaintiff “is not entitled to be placed in a better position than he would have… if the contract had not been broken.” This new pool, while not important enough to the plaintiff to rebuild alone, will probably be worth more than the current value of the land by virtue of the defendant’s “practice” run. This places the plaintiff in a better position than he otherwise would have been, a distinct violation of precedent. Specific performance is not an option in this case, and thus neither is the $33,000 of expectation damages – both would increase the value of the plaintiff’s land, which has not suffered from the building of this modified pool. Finally, if breach is found, damages must not be awarded in such a way to condone economic waste. The Groves decision, reversing and remanding instead of granting damages for what would have resulted without a contract, does not apply here in that giving our plaintiff exactly “what he was promised” presents a case of economic waste. The decision notes “the law does not require damages” involving “economic waste” with unreasonable costs. The Groves case was decided in the absence of such waste, with the defendant benefitting directly from the breach – he removed the best gravel for his own use. The case at hand instead involves waste, in the form of demolishing a functioning structure, and this must be considered – the value of the pool has not changed, but rebuilding the structure detract from the defendant’s ability to contribute to social welfare through another job. Peevyhouse v. Garland Coal and Mining Co. (1962) involves similar questions of waste – the plaintiff’s land value seemed negligible in the face of the large costs for the defendant to restore the land as the contract stipulated. The court found the “cost of Crosby 5 performance” can only be instituted as damages (i.e. the $33,000 here for new construction) “if this is possible and does not involve unreasonable economic waste.” It is the feeling of this counsel that here, as in Peevyhouse, “‘economic waste’ refer[s] to… the destruction of a substantially created building,” or the pool and its enclosure. The defendants in Peevyhouse, and Groves blatantly breached part of their contracts meant to benefit the promisees. Here, however, the defendant delivered essentially what was promised and likely at a benefit for the plaintiff, and so efficiency issues are more salient than punitive or restorative damages. The pool still functions as a pool – it is safe to dive in, differs in depth by less than 1 foot, and will not be rebuilt if the defendant defeats the complaints brought against him. Thus, it is a rough equivalent of the efficiency that would have been reached if the defendant completely fulfilled the contract. Peevyhouse’s main points consider damages in the light of “economic waste” and “relative economic benefit” – both of which avoid destroying a functioning structure. To allow the larger damages amount would be to grant a larger amount than the plaintiff “could have gained by the full performance” of the contract – he would get essentially two pools and buildings. This constitutes an inefficient outcome, wasting time, money, and the livelihood of the defendant. The possible precedent set by penalizing an efficient change in contract, granting damages of $4,000, is that of frivolous lawsuits and incentivized claims of breached contracts. Promisees can see this case as permission to create extremely specific, and thus inefficient, contracts that promisors are unlikely to fully complete. This constitutes a waste of time and money for the legal system and promisors, all for the sake of promisees requesting unrealistic contracts. Granting the plaintiff here even acknowledgment of breach serves to dissuade efficient breaches of contract, harming greater social welfare. Promisors would waste time and money redoing contracts that would have been satisfactory, if not perfect, in their original form.