Easements and Profts

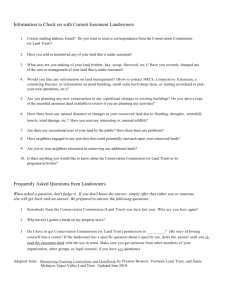

advertisement