Love - Katrina Maree

advertisement

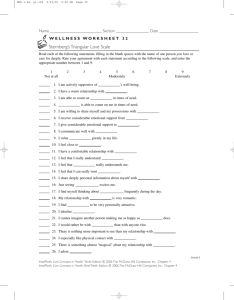

Katrina Wright HUMA-1100 What is Love: Baby Don’t Hurt Me Love. We all talk about it, see it on TV, witness it first and second hand, and have an idea of what it means to us; but what is it really? Is love something procured by media executives to enhance sales? Is it the lightheaded feeling we get in the pit of our stomachs whenever we think about a certain someone? Is it an excuse to procreate? The dictionary gives love five definitions and considers it both a noun and verb, meaning it is a thing and an action all in one. The definitions are as follows: 1. a profoundly tender, passionate affection for another person; 2. a feeling of warm personal attachment or deep affection, as for a parent, child, or friend; 3. sexual passion or desire; 4.a person toward whom love is felt, beloved person, sweetheart; 5. (used in direct address as a term of endearment, affection, or the like): Would you like to see a movie, love? 1 But what does this all mean, and how do each of us feel and use love in our daily lives? People are all so unique and diverse, how is it felt worldwide and what changes to cause the experience to be different for everyone? Scientifically, love can be described and divided into three different ideas based on patterned research over time: chemical, theoretical, and evolutionary. Love can be chalked up to a simple chemical reaction in the brain. Dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin are more commonly found during the attraction phase of a relationship. Oxytocin and vasopressin seemed to be more closely linked to long term bonding and relationships characterized by strong attachments. Sternberg (1986) introduced a triangle model of love that has three dimensions. Depending on the strength of any of those three dimensions will dictate what type of "love" that may be. For example, if someone has a high level of passion, but very little commitment, then that relationship may be simply infatuation. 2 For Fisher (1994), love is a deep seated brain activity that has evolved over thousands of years due to the survival advantages monogamy affords a helpless offspring. Fisher also classifies love as composing of two dimensions, attraction and attachment. The Sternberg Theory addresses the maintenance of close relationships by continuing to keep each of the 3 dimensions exercised. Relationships need passion, intimacy, and commitment for it to be truly fulfilling and enduring. Fisher (1994) on the other hand believes that our falling in and out of love tends to be cyclical with other mammals and breeding cycles. Thus, we may be preconditioned to be monogamous during periods, and then become restless and wander during other periods. This is commonly referred to as the "4 year itch". 3 While these theories on love have been shown over time, they are still unable to be proven as fact (just as all other theories), meaning they could change or be proven false at any time. We see love portrayed and convened to us through many different forms. Some of us have parents that love one another and we can exhibit it firsthand in a home environment; others may have parents who have deep anguish towards the other and we grow up with a distorted view of what love can and might look like. Another good source of “seen” love comes from the media. We unknowingly have it constantly shoved down our throats on a daily basis, subconsciously associating the feelings of love with products and images, and we build a perception of love and what it is based on what we see. If a person watches any romantic comedies/dramas/etc, they can see love in a form that is nearly unrealistic and sometimes frightening. Whether we like it or not, most people base a lot of their lives on what they see on TV, and when the media shows love as something outlandish and unattainable for the average person, it conveys a hopeless feeling because we are unable to acquire the love we see in movies, commercials, and other forms of media. Media Awareness Network compiled a list of stereotypes 4 often associated with the male. They include: The joker, the jock, the strong, silent type, the big shot, the action hero, and the buffoon. Males are often portrayed as heterosexual, they are more related to the public sphere of work, they reinforce the idea that men are linked to masculinity, power, dominance and control, and those of them who aren’t Caucasian exhibit more problems on average. Women were described in a completely opposite stereotype light and were more often associated with the femme fatale, the supermom, the sex kitten, the nasty corporate climber; they are mostly white, skinny, attractive (unless they are playing a comical role), and normally dressed up more than an average woman would be. Women are also more often associated with food, diet, household chores, and mothering. For example, how often do you see a man using a Swiffer or preparing a meal? Seeing these roles growing up and having them constantly repeated no matter where we are can drill the idea into our heads that women and men are required to behave a certain way in relationships, leading to a distorted perception of love. These stereotypes can encourage us to stay in something that is unhealthy or dangerous simply because we are trying to live up to the “celebrity image” that is love. We all want the beautiful, rich, ambitious, romantic, spontaneous, amazing lover that we see in films, but we have to find that in ourselves and inspire it for our relationship to succeed. Doing research and having a small, yet varied group of individuals both male and female ages 862, it was surprising how often people of all ages felt the need to conform to the type of love they’ve witnessed through the media. Three-fourths of all applications filled out concluded that people associated more with the stereotypical male and female roles in life. Women had a much more romantic idea of love and what it entails, most of them sounding straight out of a romantic movie; while the majority of my male participants included a response that was similar to a joke (many stating that to them love meant food, inanimate objects, and sexual favors and chores from their wife), leading me to believe that they are more uncomfortable with expressing their emotions than females. Most men in the media are also seen this way, rarely crying, feeling shame, sympathy, or other “weak-appearing” emotions, while women are usually crying or being over-emotional to compensate and it appears completely normal. Another common trait I noticed was that children had a more fantasy-like idea of love and the older adults became, the more cynical their descriptions. Men are stuck in their provider roles, seeing relationships and love as more of something that is supposed to be, while woman are in a “damsel in distress” state and keep waiting for Brad Pitt to sweep them off their feet with stalker-ish tactics and over-the-top pleas for their affection. Much of our roles in relationships can be derived from what we see, and sadly, it hasn’t been shown the best. Males and females correlate their responsibilities in love based on poor examples from the media and possibly their parents and other adult relationships they’ve witnessed. Love cannot be forced, controlled, or changed; it has been shown to be a simple chemical reaction in our brains that targets both good and bad feelings and our rewards center, boosting or depressing us based on effort and result. Love will always be something else to someone else, but what it means to us and the person we are in love with is the most important aspect of it. We cannot base our own relationships with love off of what is portrayed on TV or by others because each person is unique and thus each experience with love will vary. Love can be whatever we create of it, but no matter how you size it up, it is love; unexplainable, emotional, overwhelming, and amazing all at once. References: 1 http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/love 2 Fisher, HE (1994) The Nature of Romantic Love; The Journal of NIH Research 6#4:59-64. Reprinted in Annual Editions: Physical Anthropology, Spring 1995 3 Sternberg, 4 R. J. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review, 93, 119–135. 2007 Media Awareness Network; http://www.media-awareness.ca/english/issues/index/cfm