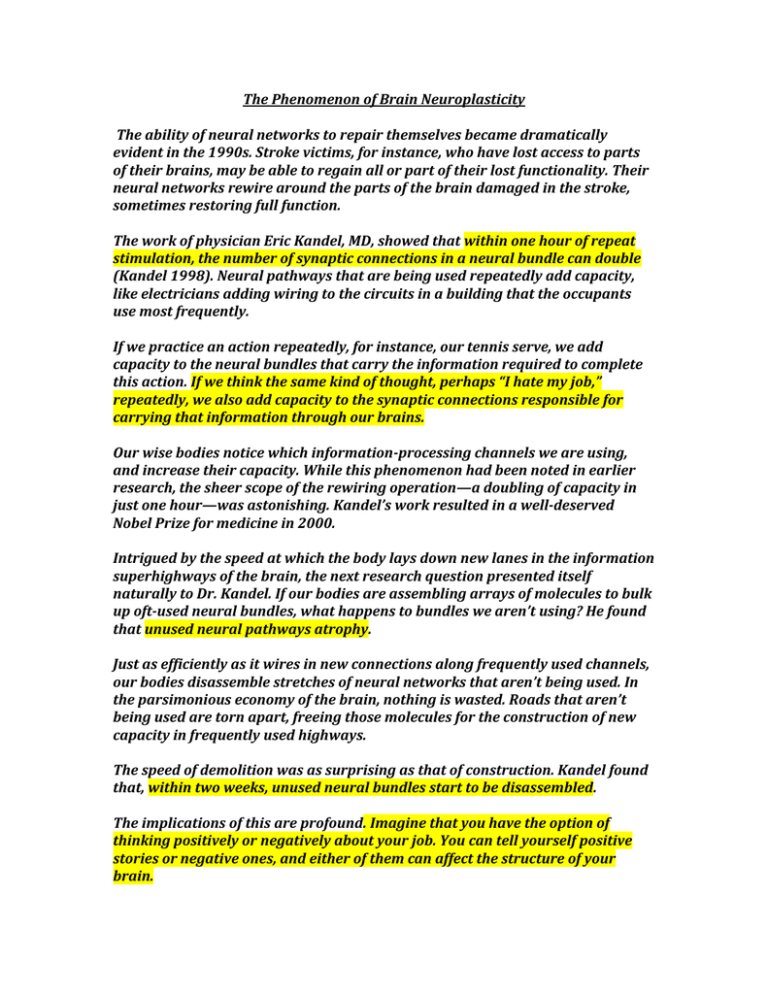

The Phenomenon of Brain Neuroplasticity

advertisement

The Phenomenon of Brain Neuroplasticity The ability of neural networks to repair themselves became dramatically evident in the 1990s. Stroke victims, for instance, who have lost access to parts of their brains, may be able to regain all or part of their lost functionality. Their neural networks rewire around the parts of the brain damaged in the stroke, sometimes restoring full function. The work of physician Eric Kandel, MD, showed that within one hour of repeat stimulation, the number of synaptic connections in a neural bundle can double (Kandel 1998). Neural pathways that are being used repeatedly add capacity, like electricians adding wiring to the circuits in a building that the occupants use most frequently. If we practice an action repeatedly, for instance, our tennis serve, we add capacity to the neural bundles that carry the information required to complete this action. If we think the same kind of thought, perhaps “I hate my job,” repeatedly, we also add capacity to the synaptic connections responsible for carrying that information through our brains. Our wise bodies notice which information-processing channels we are using, and increase their capacity. While this phenomenon had been noted in earlier research, the sheer scope of the rewiring operation—a doubling of capacity in just one hour—was astonishing. Kandel’s work resulted in a well-deserved Nobel Prize for medicine in 2000. Intrigued by the speed at which the body lays down new lanes in the information superhighways of the brain, the next research question presented itself naturally to Dr. Kandel. If our bodies are assembling arrays of molecules to bulk up oft-used neural bundles, what happens to bundles we aren’t using? He found that unused neural pathways atrophy. Just as efficiently as it wires in new connections along frequently used channels, our bodies disassemble stretches of neural networks that aren’t being used. In the parsimonious economy of the brain, nothing is wasted. Roads that aren’t being used are torn apart, freeing those molecules for the construction of new capacity in frequently used highways. The speed of demolition was as surprising as that of construction. Kandel found that, within two weeks, unused neural bundles start to be disassembled. The implications of this are profound. Imagine that you have the option of thinking positively or negatively about your job. You can tell yourself positive stories or negative ones, and either of them can affect the structure of your brain. If you think a negative thought repeatedly, you literally rewire your brain. Same with a positive thought. Henry Ford was no neuroscientist, but his famous maxim foreshadows the work of pioneers like Kandel: “Whether you think you can, or think you can’t, you’re right.” Chiropractor Joe Dispenza, in his book Breaking the Habit of Being Yourself, stresses that we have to build the neural wiring to perceive a positive reality, in the absence of material evidence of that reality, in order to be able to perceive that reality when it shows up (Dispenza 2012). If we haven’t built the neural capacity to perceive it, we don’t see our desired reality even when it’s right before our eyes. Neural plasticity works for us or against us. When a stroke victim regains full function by rewiring around the areas of the brain damaged by the stroke, or when a positive thinker rewires her brain to perceive a positive outcome, we use neural plasticity to our advantage. That’s the light side of the phenomenon. There’s a dark side to neural plasticity. When the negative thinker repeats those thoughts hundreds of times, for thousands of days, that person reinforces corresponding pathways in the brain. On the brighter side, scientific work in the field of memory reconsolidation shows that there are periods during a therapeutic experience when a window of “lability” opens up, and long-standing behaviors can be disrupted. Once the association between a traumatic memory and the body’s stress response is broken, it stays broken. Neural networks then begin to rewire themselves to carry new and more supportive behaviors and thoughts. The realization that we can rewire our brains, both creating new neural pathways, and disassembling old ones, gives us phenomenal power as individuals. You may not be able to change the objective facts of your childhood, but you can certainly change the subjective frame through which you see them.