Descartes

advertisement

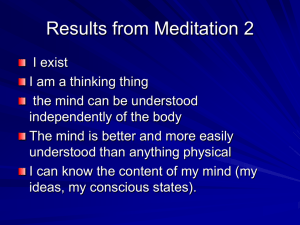

Phil 10100 Introduction to Philosophy Spring 2012 Part 2 Professor Marian David Friday Sections with TAs 2 Old Worldview • Pythagoras; Eudoxus and Aristotle (c. 350 BC); Ptolemy (c. 150 AD) • Geostatic and Geocentric • Two realms: the Heavens and the Earth—absolute division • Earth (sublunar) – is a globe (Pythagoras, Erathostenes (c. 200 BC)) at rest and at center of universe; 4 elements (earth, water, fire, air): change, decay, imperfection. • The Heavens (supralunar) – are transparent crystalline spheres revolving around center (for fixed stars and for each planet); all force comes from outside (from prime mover); heavenly things made from 5th element (the quintessence): perfection, no change, only perfect motion = circular motion (Pythagoras) • Epicycles – needed to explain retrograde motion of planets consistent with uniform circular motion. 3 4 Readings for Thursday, February 9 • No new readings • How did Erathostenes figure out the circumference of the earth? 5 I. Heliocentric and Geodynamic Worldview – Aristarch of Samos (c. 250 BC); Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, Kepler, Galileo, Newton • Sun at center of planetary system. • Earth is in daily and annual motion. • No fundamental divide between heavens and earth. – 1543: N. Copernicus: On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres Andreas Vesalius: The Structure of the Human Body – 1609: J. Kepler: Astronomia Nova • – Planets’ paths are elliptical; Kepler’s laws 1610: Galileo: The Messenger from the Stars • Telescope: Many stars Milky Way; Moon is imperfect; Venus has true phases and changes apparent size; Moons of Jupiter – 1644: Descartes: Principles of Philosophy – 1687: Isaac Newton: The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy • Classical physics of matter and motion; subsumes Astronomy; highly mathematized, axiomatic system 6 • New picture goes radically against observation and common sense! – Observed motions are illusions! • Observational evidence for new view is actually rather thin. • What supports the new view? – Simplicity: It provides a better explanation of the data; no epicycles – But only okay fit with data – Phases of Venus: only direct observational evidence against old view – Galileo’s defense against objections • Serious problem: no stellar parallax observable 7 II. Law of Inertial Motion • Galileo (circular); Descartes (rectilinear); Newton • The law becomes the cornerstone for entire modern physics—its final formulation by Isaac Newton (1687): – “Every body perseveres in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a straight line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed thereon.” • Inertia conflicts sharply with Aristotle’s physics • Aristotle: natural vs. violent motion: – Its natural motion is intrinsic to a thing (due to an inner principle of activity) – Violent motion requires an external force – Generates serious problems: law of inertia dissolves them 8 • Galileo – famously uses inertia to respond to common sense objections to Copernicanism, – applies same laws of motion to planets and earthly bodies against Aristotle’s divide, – relies heavily on idealizations and thought experiments, – real experiments and observations are used only for testing his views. Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) Notorious conflict with the church: Galileo’s Trial 9 Readings for Tuesday, February 14 • René Descartes: Meditations on First Philosophy, – Meditation One – Letter of Dedication (margin 1-6) – Editor’s Preface – Meditation One 10 III. Atomism and Mechanism • Atomism (ancient) – Democritos (c. 400bc), Epicurus (341-270bc), Lucretius (c. 50bc, De rerum naturae) • Aristotle was no atomist! – All matter is ultimately constituted by tiny indivisible material particles = atoms. – Ancient atomism arose from debate about constancy through change: “All there is are atoms and the void” (Democritus); change is rearrangement. – Aims at reductive explanations: Big things are aggregates of little things; properties of big things can be explained by properties of little things. • Mechanistic Philosophy (modern) – Physical world = particles of matter in motion, governed by mechanical laws. – Law of inertia is basic. – Bodies change direction on impact (contact) with other bodies. – Nature explainable in terms of (mathematizable) laws governing the motion of particles. • No action at a distance; no teleological explanations – Model: mechanical clockwork. 11 • Atomism is mostly non-empirical: – Atoms are not observable; – Deep structure of reality very different from how it appears; – Sensible qualities of things are mostly illusions: • Galileo: “Heat is motion”!! • Primary and secondary properties 12 • Anti-Empiricist diagnosis of Scientific Revolution: Don’t trust sense experience! – The new science goes against common sense and observation: • Appearances are misleading and need to be corrected by reason • Appearance vs. reality / Observation vs. theory – Undermines trust in God-given senses? but intellect is God-given too? – Push towards rationalism – Mathematization of Science – [An exaggeration, overreaction?] • Takes us to Descartes 13 René Descartes (1596-1650) • French catholic • Mathematics! • Physics! • Biology • Philosophy! 14 Cartesian Coordinates 15 Meditations on First Philosophy (1642) Letter of Dedication • God and the Soul are proper subjects for philosophy (science) not just for theology. – Lateran Council • Geometry – held up as model of certainty • Withdrawal from the senses! – partly a reaction to scientific revolution 16 Meditation I • Goals – avoiding false beliefs & attaining true beliefs – a stable belief system: certainty • Method of Doubt (MoD): – Search for indubitable first principles (foundations of knowledge) by way of doubting one’s opinions: – Retain only those opinions whose truth is indubitable, discard all others! • MoD attacks the reliability/trustworthiness of the senses! – Marg. 18: “Surely…”. – Compare medieval slogan: Nihil est in intellectu quod non prius fuerit in sensu (nothing is in the intellect that was not previously in sense); e.g. Aquinas, De Veritate, Q.2, A.3. 17 • Three reasons for doubting beliefs based on sense perception: 1. Senses are sometimes deceptive [not very strong] 2. Dream Argument 3. Evil Demon Argument • General Structure of D’s arguments: I could have the same sense experiences I am having now, even if all my perceptual beliefs were false, see 1, 2, 3. Therefore: My perceptual beliefs are not indubitable; they don’t pass the MoD test. • Upshot of Med I: – “But eventually…”; see marg. 21, end. – None of my beliefs about the world are indubitable. – Nothing is certain? 18 • Sense Perception: – In sense perception we form beliefs about how things are, based on our sense experiences; – that is, based on how things look, feel, sound, taste, smell to us; – that is, based on how things appear to us. • Are our perceptual beliefs true? – Are things really like they appear to us in sense experience? – Are there even any things there at all? • Appearance vs. Reality 19 • D’s skeptical hypotheses (reasons for doubt) throw in-principle doubt on our beliefs about: – material things (bodies) – your own body (including brain) – other persons (including God) – the past • Cartesian Doubt is radical. – ! Note: D does not say that our ordinary opinions are false; – he does not even say they are not reasonable or not probable; see marg. 22. • Does he actually doubt these things? – Maybe not but: P is not doubted ≠ P is indubitable 20 Readings for Thursday, Feb 16 • Concourse – Item 6: Huemer, Skepticism • Descartes: Meditations on First Philosophy, – Meditation Two – Meditation Two – Meditation Two – Question: In Meditation Two, is Descartes arguing that his mind is not (part of) his body? 21 22 • Distinguish: – believing / disbelieving / withholding – The ordinary formulation: “I don’t believe that we’ll win the next game” is ambiguous (and can be misleading): a. I believe we won’t win b. I neither believe we’ll win nor believe we won’t win; I withhold judgment 23 • Skeptics (historical): – They doubt that we have any knowledge about the world – Various ancient schools from Greeks up to late antiquity: • Pyrrhonists and Academic Skeptics – Goal: agnosticism (= withholding judgment) to achieve peace of mind • Descartes’s Methodological Skepticism: – Doubt as a method to reach indubitable truths – Hyperbolical doubt → probability is not good enough: certainty – Motivated by perceptual illusions – Motivated by upheaval in the sciences! – Descartes wants to build the new science on firm foundations so that it cannot suffer the same fate as the old science. • Anti-Empiricist Diagnosis of Sci. Rev.: Don’t trust sense experience!! 24 Meditation II • Descartes finds some indubitable truths: the Cogito (m. 24-25): • Cogito ergo sum = I think, therefore, I am I exist I think • When I am thinking that I exist, then what I am thinking is true. When I am thinking that I don’t exist, then what I am thinking is false. • When I am thinking that I am thinking, then what I am thinking is true. When I am thinking that I am not thinking, then what I am thinking is false. 25 • What am I? – that is: What is a person? – Method of Doubt reapplied to this question. • Aristotle: A person is a body + a soul. vegetative sensitive intellectual (noûs) (Three aspects/parts of the soul) • Descartes: – Am I a body? doubtful ☹ – Am I a soul? a vegetative soul? a sensitive soul? ☹ ☹ an intellectual soul (noûs)? ☺☺☺ • I am a thing that thinks! 26 Descartes’ Definitions • x is a mind = x is a thinking thing – that is, a thing that doubts, understands, affirms, denies, wills, refuses, and also imagines and senses…(m. 28; later also: feels) – broad notion of thinking • x is a body = x is an extended thing – extended in three dimensions – broad notion of a body = a material thing • Note well: – Descartes has not argued (yet) that he is not also a material thing: as far as he knows (so far), he could still be a body! (m. 27) – “I am not certain that I am a body” ≠ “I am certain that I am not a body” 27 Descartes’ Axioms • “I think” and “I exist” serve as the most basic axioms: – absolutely certain and indubitable, known by intuition, – but not necessary truths: they are contingent, – but not universal truths: they are about myself. • Necessary truth: a proposition that is true and could not possibly be false; • Contingent truth: a proposition that is true but could have been false. 28 Descartes’ Program: • Show that axioms about my self (my own mind) serve as foundations for all my knowledge about the world—to the extent that I have such knowledge. – Model: Euclid (see D’s introductory letter)! – Note that only Euclid (and Logic) survived the scientific revolution! • Only two axioms?! – That does not look promising! 29 • More axioms (m. 29): My beliefs about my own mental states, that is, my beliefs about the present contents of my own consciousness: – My beliefs about how things appear to me now; – My beliefs about how I feel now (about my pain, pleasure, etc.); – My beliefs about my own present beliefs, doubts, desires; – That is, my beliefs about my present “modes of thinking” (m. 34-35). • All such beliefs of mine are indubitable – They can serve as foundations for my knowledge about the world (if any), – or so D seems to maintain. • My knowledge about the present contents of my consciousness does not come through sense perception! – I do not see with my eyes (smell, taste, hear, touch) the contents of my consciousness. 30 The Wax Argument (second half of Med II; margin 29-34) • Ordinarily, we think what we know best are the bodies (material things) surrounding us, which we know through sense perception. • Descartes rejects this: What we know best are our own present mental states, and we do not know them through sense perception; we know them by “looking inside”, through “the mind’s eye”. • D even argues (suspending the MoD) that what we really know of material things in sense perception we know through the mind: – The piece of wax: its sensible qualities all change when the wax is melted. – Yet we know that the same wax remains, that it is the same thing. – So this is not knowledge about the sensible qualities of the wax but about its nature as an extended, flexible (= material) thing. – These properties are too abstract and too rich to be known through sense experience or even the imagination: they are known through the intellect. – Hence, what we really know about the wax (if anything) we know through the intellect. – But we say we “see” the wax! – That’s just a manner of speaking. What we call “seeing” is really an inference, where the intellect applies its non-perceptual ideas of body (extension) to the perceptual ideas supplied by the senses. 31 Readings for Tuesday, February 21 • Concourse – Item 7: Descartes, from Rules for the Direction of the Mind • Descartes: Meditation Three – up to & including first paragraph of margin 40! – At least two times! 32 33 Meditation III (First Part) • The Rule: Whatever I understand very clearly and distinctly is true. – D says “perceive” – D gets to this rule by reflecting on Cogito and MoD – D wants to use it to derive theorems from his axioms – clear & distinct ≈ what survives the MoD • Problem: – I used to think that sense perception is clear & distinct, but MoD showed it isn’t. ↓ • Analysis of sense perception into two aspects: – Ideas and the judgments we make (beliefs we form) based on our ideas. 34 I can have no knowledge of what is outside me, except by means of the ideas I have within me. Descartes Human souls perceive what passes without them by what passes within them. Leibniz 35 Descartes’ Theory of Ideas: A.k.a. The Representational Theory of the Mind – The mind is a thinking thing. – Thinking is the processing of ideas. – Ideas are “the stuff” thoughts are made of: parts of thoughts. – Ideas are mental representations of things and properties. – They mediate our access to the world (if any). – Ideas are objects of immediate awareness. • Distinguish complete thoughts from ideas: – The thought THAT GOD EXISTS vs. the idea GOD; the idea EXISTENCE. – The thought THAT I HAVE A HAND vs. my idea of MYSELF; my idea of my HAND. 36 • Sense Perception – is indirect, inferential: it involves making tacit judgments: – When I “see” that there is a grey cat, I am directly aware of my grey-cat idea; based on this I judge that there is a grey cat in front of me; – Normally, I trust that my grey-cat idea is an accurate representation of reality. • Naïve Assumption of Accuracy (m. 35, 38-9): Our naïve trust in the reliability of sense perception relies on the two-fold assumption that our ideas accurately represent an external world, i.e., • (i) that our ideas are caused by external objects; • (ii) that the external objects that cause our ideas also resemble them. • This assumption is a natural one to make: – But is it right? Is it just a “blind impulse”, or is it reasonable? – How can it be vindicated? 37 The Problem of Our Knowledge of an External World • 1. I have indubitable knowledge of my own existence and my own mind (that is, of the present states of my own consciousness, of my present ideas); 2. Based on this, how can I demonstrate (prove): – that there are material things (including my own body)? – that there are other minds (including God)? – that there was a past? external: to consciousness, not to my body or my skin or my skull. 38 Some Remarks • Descartes’ strategy in the rest of Meditations: – prove that God exists; – prove that He is not a deceiver; – then use this to tackle the external world problem. • Descartes sets agenda for modern philosophy: – Knowledge of internal world is available; – How do we get knowledge of external world? How do we get outside the theater of our own ideas? – Philosophers after Descartes all accepted the underlying framework: the theory of ideas (the representational theory of the mind). – But few believed that his specific strategy for tackling the external world problem would be successful. – Main difficulties: God and causation. 39 • Distinguish the idea of X from X! – My idea of the sun ≠ the sun – My idea of my wealth ≠ my wealth • One cannot, in general, prove the existence of X from the idea of X! For most X: I have an idea of X X exists • is invalid ☹☹☹ Are there any special Xs for which this sort of argument is valid (special cases)? – Yes: X = myself → Cogito – Descartes holds that there is one other special case: X = God → but this is not indubitable, it needs proof. 40 Readings for Thursday, Feb 23 • Descartes, Meditations – Second half of Meditation Three (margin 40-52) • Watch out: “objective reality” means the opposite of what you think it means! • Concourse – Item 1: Glymour, section: “God and St. Thomas”. 41 42 Meditation III (Second Part): Descartes’ Trademark Argument for God’s Existence • • Two closely related arguments in Med III: – Margin 40 to end of 47 – End of margin 47 to 51 An argument for the existence of God? – • Catholic Dogma: God, our Creator and Lord, can be known with certainty, by the natural light of reason from created things (De fide.)* Compare Descartes and St. Thomas: – Both employ causation; – But Descartes starts with a premise about his own mind: “I have an idea of God”. * Ludwig Ott, Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, (Tan Books 1960), p. 13. 43 Simple Version of Trademark Argument 1. I have an idea of God. 2. My idea of God represents an infinitely perfect being. 3. I could not have such an idea, if there were no infinitely perfect being outside me. Therefore 4. An infinitely perfect being, i.e. God, exists outside me. • • Med III, Margin 40 to end of 47; esp. 42. Note that Descartes himself does not use “idea…represents” in the argument; instead he talks of the “objective reality of an idea”. Note that Descartes puts his argument in terms of perfection/reality ≈ independence of being. • 44 • Pr1: Do we have an idea of God? Yes! (see m. 45) ✓ • Pr2: If someone’s so-called “idea of God” does not include ∞, too bad for them. ✓ • Pr3? • Watch Out! – Do not say: “It’s an infinitely perfect idea, hence…” – It is an idea of infinite perfection; – It represents infinite perfection; – This does not entail that the idea itself is infinitely perfect. 45 46 Argument for Premise 3 5. Everything must have a cause. Hence 6. The fact that my idea of God represents an infinitely perfect being must have a cause that is infinitely perfect. 7. I am not infinitely perfect. Therefore 3. I could not have an idea representing an infinitely perfect being, if there were no infinitely perfect being outside me. 47 • Premise 7: – If there were infinite perfection in me, I couldn’t fail to notice it. ✓ • Step from premise 5 to 6: – Descartes thinks that my idea couldn’t have the power to represent infinite perfection, unless it were caused by something infinitely perfect. Is that indubitable? – Idea of infinity is crucial to the argument: “I could not have borrowed it from myself”, D says. – But could I have put it together from other ideas: e.g. of finite and not? – Ludwig Feuerbach and Karl Marx (19th cent. German): Idea of God is just a projection from our limitations, fears, and unsatisfied desires. 48 • Premise 5: • The principle of causation: Everything must have a cause. – is it true? – needs slight revision: – Every contingent thing must have a cause. • A contingent thing/being is a thing that exists but could have failed to exist; it does not exist necessarily, it is not a necessary being. – is it indubitable? did he run it through the MoD? • Upshot? 49 Afterthoughts about Trademark Argument • Descartes: The idea of God does not come from the senses: it is innate, like the idea of myself. – See margin 51. – Distinguish the idea of God, and the idea of existence, from the claim that God exists. • Why is the argument called the “Trademark” argument? – See margin 51. 50 The Babel Fish Argument for the Non-Existence of God from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams The Babel fish is small, yellow and leech-like, and probably the oddest thing in the Universe. It feeds on brainwave energy received not from its own carrier but from those around it. It absorbs all unconscious mental frequencies from this brainwave energy to nourish itself with. It then excretes into the mind of its carrier a telepathic matrix formed by combining the conscious thought frequencies with the nerve signals picked up from the speech centres of the brain which has supplied them. The practical upshot of all this is that if you stick a Babel fish in your ear you can instantly understand anything said to you in any form of language. The speech patterns you actually hear decode the brainwave matrix which has been fed into your mind by your Babel fish. Now it is such a bizarrely improbable coincidence that anything so mindbogglingly useful could have evolved purely by chance that some thinkers have chosen it to see it as a final and clinching proof of the non-existence of God. The argument goes something like this: "I refuse to prove that I exist," says God, "for proof denies faith, and without faith I am nothing." "But," says Man, "the Babel fish is a dead giveaway isn't it? It could not have evolved by chance. It proves you exist, and therefore, by your own arguments, you don't. QED." "Oh dear," says God, "I hadn't thought of that," and promptly vanishes in a puff of logic. "Oh, that was easy," says Man, and for an encore goes on to prove that black is white and gets killed on the next zebra crossing. Most leading theologians claim that this argument is a load of dingo's kidneys, but that didn't stop Oolon Colluphid making a small fortune when he used it as the central theme of his best-selling book Well That About Wraps It Up For God. Meanwhile, the poor Babel fish, by effectively removing all barriers to communication between different races and cultures, has caused more and bloodier wars than anything else in the history of creation. 51 Meditation IV: Concerning the True and the False • Descartes: “God is not a deceiver” – Argument: God is infinitely perfect; hence, He has no imperfections. Therefore, He is not a deceiver, because “it is manifest by the light of nature” that deception stems from a defect. – See end Med III, marg. 52, (reference to light of nature is code for “clear and distinct”) and Med IV marg. 53. • The Problem of Error: If God is not a deceiver, doesn’t that make erroneous judgment impossible? – That would be a reductio ad absurdum of Descartes’ argument. – Compare with the Problem of Evil. 52 Readings for Tuesday, Feb 28 • Descartes, Meditations – Meditation Four – Meditation Five • Concourse – Item 1, Glymour: “God and Saint Anselm”, pp. 15-17. – Item 7, Thomas Aquinas: “Omnipotence” • Midterm exam: – Friday, March 2, = a week from tomorrow, in discussion section. – Material: Everything up to and including Th, March 1. – You might want to begin reviewing things over the weekend. – Format. 53 54 Meditation IV • Descartes: “God is not a deceiver” – Argument: God is infinitely perfect; hence, He has no imperfections. Therefore, He is not a deceiver, because “it is manifest by the light of nature” that deception stems from a defect. – See end Med III, marg. 52, (reference to light of nature is code for “clear and distinct”) and Med IV marg. 53. • The Problem of Error: If God is not a deceiver, doesn’t that make erroneous judgment impossible? – That would be a reductio ad absurdum of Descartes’ argument. – Compare with the Problem of Evil. 55 The Problem of Evil and the Free Will Defense • Presence of evil seems incompatible with existence of God, an omnibenevolent, omniscient, and omnipotent being. • Free Will Defense: • Boethius, 5th cent. – Freedom is a very great good; – Our freedom enables us to do bad things; – Not even God can create a world with genuine free beings and keep them from doing bad things; • Note: It’s crucial for this claim that doing this would imply a contradiction and that not even God can do things that imply a contradiction. – Basic Thought: The goodness of freedom may be so great (∞) that it outweighs all the bad things that come in its wake. • • It’s sufficient for the defense, if this is at least possible. Imagine God, just before creation, weighing possible worlds. 56 • Descartes’ theory of judgment: Judgment results from the cooperation of two faculties: the will and the understanding: 1. The understanding provides me with ideas to judge about; it is finite and imperfect: • I lack ideas of many things • Many of the ideas I do have are confused (= not clear and distinct). 2. The will is as close to infinite and unlimited as humans can get: the will is free! • Autonomy of persons; “created in God’s image” (marg. 57) • A judgment comes about when I decide freely to affirm or deny the ideas presented to me in my understanding. • So Descartes uses a modified Free Will Defense to tackle his problem. 57 • Error results from my misuse of my free will. – Erroneous judgment comes about when I decide to make judgments involving ideas that are not sufficiently clear to me (m. 58). – I deceive myself! – It is my fault, my imperfection, not God’s. – Why did God allow me to deceive myself? The goodness of my freedom of will outweighs the badness brought about by my erroneous judgments. • As long as I judge only what I understand clearly and distinctly, I cannot go wrong. – End of marg. 59 to 60; marg. 62. 58 A worry: • Is judgment really free? – Distinguish assertion from belief. – Is belief free? Is believing under our voluntary control? • Can I believe that p just because I want to believe that p? • Can I refrain from believing that p just because I don’t want to believe that p? – Dubious. 59 Meditation V: Concerning the Essence of Material Things, and… • Ideas of material objects – Primary (quantitative) vs. secondary (qualitative) ideas. – This connects with his survey of his ideas in Med III, marg. 43-45. • Primary ideas – Ideas of extension, position, motion, number, duration and their sub-ideas. – They are clear and distinct . • General laws of pure mathematics and pure mechanics – involve only primary ideas; – are pure because they are existence neutral. – We find these laws by analyzing what is contained in our primary ideas: Definitions and their logical consequences. 60 Descartes’ Ontological Argument for God’s Existence • Compare with the version given in the 11th century by Anselm of Canterbury (Concourse, Item 1: “God and Saint Anselm”). • The argument is supposed to be like a geometrical proof. • 1. God is a being that has all perfections 2. Existence is a perfection 3. God exists Premise 1 is supposed to follow from the definition of God, just like “A triangle has three sides” follows from the definition of a triangle. 61 • Premise 2: “Existence is a perfection” – This does not imply: If x exists, then x is perfect!! – Existence is a perfection. – P is a perfection = P is a property “contributing” to perfection (greatness); that is: having P makes one more perfect (better) than one would be without P. • Objection to Premise 2: “Existence is not a property” (P. Gassendi, Immanuel Kant) – Descartes: Why not? – Descartes: In any case, it’s a verbal issue, existence is presupposed by having properties/perfections; the argument can be rewritten. – Descartes: Necessary existence is a property, and the argument can be strengthened to: 62 Ontological Argument: Strengthened Version 1. 2. God is a being that has all perfections Necessary existence is a perfection 3. God exists necessarily 63 • Objection to Premise 1: “It has not been shown that the idea of God is consistent” (Leibniz) – Anything follows from inconsistent definitions. – Inconsistent definitions: • definition of “the greatest number”; • or define “the Bertrand-Barber” as the barber who shaves all those, but only those, people who do not shave themselves (Bertrand Russell). • the Bertrand-Saint, who helps all those, but only those, who do not help themselves (?) – Leibniz maintained that this objection can be answered, that the idea of God can be shown to be consistent: • If God is possible, then He is necessary. • God is possible. • Therefore, He is necessary. 64 M. C. Escher 65 66 Readings for Thursday, March 1 • Concourse – Item 7, Thomas Aquinas: “Omnipotence” • Descartes: – Meditation Six • Midterm Exam: – Friday, March 2, in discussion section. – Material: Everything up to and including Th, March 1. – One-sheet format. 67 Meditation VI: Concerning the Existence of Material Things, and the Real Distinction between Mind and Body • End of Med V: – Omnipotent deceiver (evil demon) hypothesis is refuted. – I have certain knowledge of “countless matters”: concerning God, the mind, and matter insofar as it is the object of pure mathematics and mechanics (clear and distinct, existence independent). • Do material things exist? – He knows they are possible (because they are the objects of pure mechanics). – But are there actually any material things? 68 • First argument for existence of material things (margin 73): via the nature of imagination: – aborted: only probable. • But note famous Chiliagon Argument: – Margin 72: – “Chiliagon”: a regular figure with 1000 sides. – We have the idea of chiliagon; but not from imagination or sense perception: it is an intellectual idea. – Argues for distinction between imagination and sense perception, on the one hand, and intellection, on the other hand. – See also argument at margin 64: mathematical ideas are innate. • Descartes takes a step back (margin 74) 69 • Reconsideration of sense perception (margin 74-76). – He reminds himself of the sorts of things he used to believe concerning material things based on sense perception. • Method of Doubt reapplied (margin 76-77). • Announces that the results will be mixed (margin 77-78): – I should’t doubt all that the senses have taught me; but I shouldn’t trust all of it either. • Argument for Dualism (margin 78): – “I am really distinct from my body and can exist without it”; – That is, I am only a thing that thinks, I am an immaterial thing. – [We’ll come back to that] 70 Argument for the existence of material objects (Very rough reconstruction of margin 78-80) 1. My perceptual ideas of material things must be caused by something. 2. I have a powerful natural inclination to assume that my perceptual ideas are, by and large, caused by material things outside me. 3. If this assumption were mistaken, God would be allowing me to be subject to systematic radical deception without giving me any means for detecting the deception. 4. That would be inconsistent with God’s not being a deceiver. Therefore, 5. My perceptual ideas really are, by and large, caused by material things outside of me. 71 • Shows that my ideas of material things are by and large caused by material things. – Sometimes we do suffer from hallucinations, etc. – In many respects, material things may not be like I perceive them to be, because my ideas from sense perception are often confused (idea of the sun). – But God has given me a faculty for correcting the mistakes I make due to confused ideas: the intellect → the new science. • “Nature teaches me” – Note the line of reasoning: A strong natural inclination to believe/trust something which leads me into systematic, undetectable, radical illusion is impossible: because God is not a deceiver. – When, in the following, Descartes says “nature teaches me” he refers to this line of reasoning. 72 Nature teaches me (80-81) • I have a body. • I am very closely joined/intermingled with my body. • Pain indicates damage to my body. • There are other bodies which can affect me beneficially or harmfully. • • There are certain properties in bodies that somehow cause me to have qualitative ideas of colors, sounds, tastes, hot/cold, etc. Perceived qualitative differences of bodies correspond to real differences of some sort. Nature does not teach me (82-83) • There is a void. • Apparent sizes correspond to real sizes. • There is something in bodies that resembles my qualitative ideas of them. – instead, the fundamental quantitative properties of bodies cause me to have various qualitative ideas under normal circumstances. 73 • Mechanism or “the Mechanical Philosophy” – Fundamental physical properties of material things are extension (size and shape) and motion; • other properties can be explained in terms of fundamental properties • [mass, where is mass?] – Fundamental laws of nature are mechanical laws describing bodies in motion through impact; • No action at a distance • No teleological explanations – Qualitative “properties” are not real; • Qualitative ideas are responses of the mind to the impact of material things on human body → we project these ideas onto the world and wrongly take them for real qualities of things. – Derives from ancient Atomism • Democritus, Epicurus, Lucretius – Not explicitly advocated in Meditations, but it’s waiting in the wings. 74 Sense Perception and Mechanism • Proper purpose of my sensations is to inform me about what is harmful or beneficial to my body (83) – I misuse my sensations when I treat them as reliable sources for immediate judgments about the nature of material objects – Sense perception must be corrected by the intellect → the new science. • Problem: Misleading sensations and appetites – In response D treats “a man’s body as a kind of mechanism” – Body and life are purely material, mechanical phenomena – Mind and thinking are non-material – Nonhuman animals are mere machines (no intellect) 75 • Descartes’s account of misleading sensations and appetites (84-89) – Phantom pain; harmful desires – Human body is a machine, a mechanism: same input at any point along a nerve leads to same output in the brain – The immaterial mind is “connected” to the body-machine in the brain (at pineal gland) – Phantom pain is the mind’s response to a brain event that is normally caused by damage in foot – Body-machine always follows the laws of nature, even when “it’s not working properly” (85): contra Aristotle Descartes: L’Homme 76 • End of Meditations: Response to Dream Argument (68a 3rd – 68b) 77 Readings for Tue, March 6 • Descartes: – Meditation Six, two times – When you’re done, re-read the one longish paragraph at margin 78 (p. 51) – Really • Concourse – Item 9, David on Dualism. • Midterm exam, tomorrow, in discussion section: – Material: Everything, excluding Meditation 6. 78 Divine Omnipotence • First shot definition: X is omnipotent = X can do anything. • Question: Really? – Even things that cannot possibly be done? • Aquinas says: – No way; that’s incoherent! – Summa Theologiae, Part I, Question 25, Articles 3 & 4. • Can God make a stone He cannot lift? 79 • Aquinas’ definition: X is omnipotent = X can do anything that is not absolutely impossible, that is, anything that does not imply a contradiction. • Consider: “If G cannot make a round square, then G is not omnipotent”. – This conditional is false: – Though G cannot make a round square, His inability to make a round square doesn’t show He is not omnipotent, because making a round square implies a contradiction, namely making a round thing that is not round. • Is G’s power limited by “logic”, by the (absolutely) impossible? – Aquinas says: No, because nothing that could possibly exist could limit G’s power. – To say that G’s power is “limited” by something that does not and cannot possibly exist is just a confused way of saying that G’s power is not limited by anything. – Aquinas is pointing out that the following is a trivial logical truth: What cannot be done cannot be done. 80 Continue with Part 3