non-affiliation_ESR

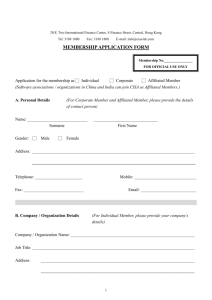

advertisement