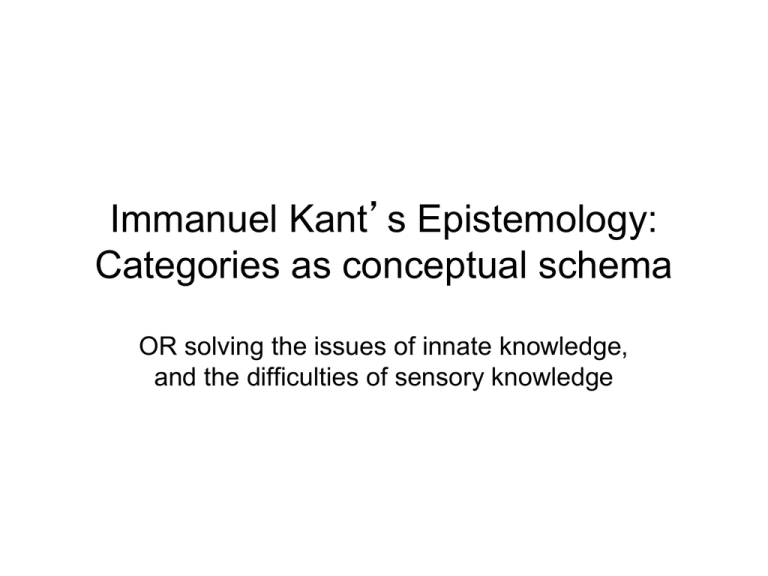

Immanuel Kant's Epistemology - History of Western Philosophy

advertisement

Immanuel Kant’s Epistemology: Categories as conceptual schema OR solving the issues of innate knowledge, and the difficulties of sensory knowledge Some anecdotes about Kant • Lord Macaulay said in 1848: "November 23d. I received to-day a translation of Kant from Ellis's friend at Liverpool. I tried to read it, but found it utterly unintelligible, just as if it had been written in Sanskrit. Not one word of it gave me any thing like an idea except a Latin quotation from 'Persius.' It seems odd that in a book on the elements of metaphysics…I should not be able to comprehend a word.” • A man of precise habits: would stroll every day, for exactly one hour, eight times up and down the same street. • The street came to be called “The Philosopher’s Walk.” • So punctual, that the housewives of Königsberg set their clocks by the time he took his walk. Life (1724-1804) • Born in Königsberg, Prussia (now part of Russia) in 1724. • Went to university in his home town and then became a professor there. • Never left his home town, never married, never traveled more than 60 miles from it, and didn’t leave it at all during a forty year stretch. • Prodigious output of philosophical work – major contributions to epistemology, deontology, aesthetics • Author of three of the greatest works in the history of philosophy. – The Critique of Pure Reason (1781) – on Epistemology – The Critique of Practical Reason (1788) – on Ethics – The Critique of Judgment (1790) – on Aesthetics • Died, very sadly, totally senile, at Königsberg in 1804. The ‘Copernican Revolution in Philosophy’ • Kant famously says that his epistemology effects a ‘Copernican Revolution’ in philosophy. • Copernicus put the sun at the centre of the solar system and pointed out that the apparent movement of the stars is partly due to the movement of the human observer. • Kant’s epistemology puts the human mind at the centre of knowledge(-making): the human observer is involved in the universe. • Hence, properties we assume belong to the world may be properties of the human mind. • Perception is an active process; the mind contributes to our experience of reality; its properties can be studied empirically, through introspection). • By doing this Kant thinks he solves many of the problems of both rationalism and empiricism. • He offers a solution that unites the insights of each approach to the world – ‘Transcendental Idealism’ Kant’s context: reaction to Hume • Kant reads Hume as a young man and is shocked: “David Hume was the very thing which many years ago first interrupted my dogmatic slumber and gave my investigations in the field of speculative philosophy a quite new direction.” ‘Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics’ (1783) • Kant disagreed with Hume’s suggestion that humans are emotional, not rational, beings, and that we should accept that reason is a very limited tool at best. • Nor could Kant abide Hume’s claim that, at best, science and philosophy are games people play to have fun, rather than ways of attaining truth. • Kant disagreed with Hume’s argument that general concepts such as those of causation and induction are simply habitually formed and not really logically grounded. More context: problems with Rationalism, and with Empiricism • Descartes’ problem, for Hume: reason as foundation of knowledge leads to empty, formally correct statements, but which don’t seem to have referents out in the world so aren’t much practical use • Hume’s problem, for Kant (and Descartes): experience as foundation of knowledge leads to useful statements, but these have a messiness and uncertainty about them that isn’t desirable • Kant agrees with empiricists that innate ideas are not viable. • Yet problems with empiricism over the acquisition of certain abstract concepts reopen the case for a priori knowledge. • He offers a solution which tries to reconcile the two approaches to the world: a formal system of a priori foundational principles for knowledge. A reminder of some basic terminology which Kant invented… • A posteriori knowledge - knowledge based on empirical facts and hypothetical truths. • A priori knowledge - knowledge of logical and transcendental truths which isn’t based in particular experience. • Analytic statement - a statement or item of knowledge known to be true because of its conformity to rules of logic. • Synthetic statement – a statement or item of knowledge that is known to be true because of its connection with some intuition. • Empirical, a posteriori sense experiences are essential for our ideas of the world to have content. Messy but useful, basically. • Analytical, a priori analytical structures are essential for unity, cohesiveness, meaning of our ideas. Precise but bland, perhaps. A key Kantian tool: Transcendental Deduction or Argument • Transcendental arguments are anti-skeptical arguments focusing on the necessary enabling conditions – either of coherent experience – or of the possession of some kind of knowledge or cognitive ability… • Transcendental arguments begin with some obvious fact about our mental life, such as some aspect of our knowledge, our experience, our beliefs, or our cognitive abilities • and add a claim that some other state of affairs is a necessary condition for the first one to exist e.g. where there’s smoke, there’s fire… • Kant uses Transcendental Arguments to identify the logically necessary structural principles for the possibility of experience. Kant’s Big Intuition: the Transcendental Deduction of Space and Time • • • Kant asks: What are the necessary a priori conditions for perception? Transcendental Argument: as we have perceptions, space and time must exist. Representation occurs, hence space and time exist. Because: perception = when we represent things to ourselves, and one cannot represent events without saying WHERE and WHEN. – SPACE: Not an objective, empirical property of the world. No empirical perception can give us the idea of ‘space’. It is the subjective and logical precondition for representation, a given. – TIME: Not an empirical sensation, but a logical, a priori structuring principle. We cannot represent phenomena without the notion of time, but we can represent time empty of phenomena, therefore the idea of time is logically necessary and prior. • • Hence Space and time exist only as productions or structural elements of the human mind, as "intuitions" by which perceptions are measured and judged. In addition to these intuitions, Kant proposed that a number of a priori concepts, called categories, also exist. What are the Kantian Categories? • A built in, “hard-wired” capacity of the human mind by which it organises and structures raw sense data • the concepts which form the conditions of possibility of human experience. • The categories are a conceptual framework or conceptual scheme in terms of which all objects of empirical knowledge are analysed or filtered. – Every perception is a two-fold reality: i) raw sense data and ii) the organizing and structuring of that data by the mind. – Sense data, in and of itself, is a meaningless jumble: everything we experience is ‘filtered’ through the categories. – If our knowledge were not filtered, we could not experience it; it makes sense only after it has been organised and structured by the mind’s categories. – KEY QUOTE: ‘Concepts without intuitions are empty; intuitions without concepts are blind.’ A descriptive analogy to help: The Coin Sorting Machine • Take a large bag of mixed coins of different types. Is there £200 there, or £25? • While they remain mixed up in the bag, the coins really have no value. You cannot buy something with a bag of coins without knowing its value. • Before you can spend the coins, you have to sort them with a coin sorter so that you know how much they are worth. • The coins don’t really have any true value until they are sorted by the coin sorter. How does this analogy help? • In this analogy, raw sense data is like the bag of mixed coins. In itself, raw sense data is meaningless jumble. • The coin sorter is analogous to the mind’s categories. • The coin sorter provides organisation and structure and, thereby, value to the bag of coins. • The mind’s categories provide organisation and structure and, thereby, meaning, to jumbled up, raw sense data. • Write your own analogy…try the rules of chess and chess pieces, glasses for a short-sighted person, containers for things contained… Kant’s Categories • There are four main categories, each divided into three subcategories. (HANDY TO KNOW THESE BY HEART…) Quantity Unity, plurality, totality Quality Reality, negation, limitation Relation Substance and accident, cause and effect, reciprocity Possibility, existence, necessity Modality The Categories are Synthetic A Priori ideas Analytic A priori A posteriori ‘Triangles have three sides’ (certain but dull) (none – nothing. No truths derived from experience are tautological. ) Synthetic Kant’s Categories – a short but important list + Mathematics (certain, but also useful) ‘Triangles were the earliest discovered geometrical shapes’ (handy e.g. in a pub quiz, but could be wrong) • Synthetic a priori ideas have utter certainty, but can only be deduced after experience. Experience lets you work out that you must have them (in order to have experience), via a transcendental argument. • Kant also sees mathematics as being composed of synthetic a priori statements because it depends on the pure intuitions of the elements of time and space. This is why maths has both a feeling of purity and certainty, yet seems to be something that is discovered. Why does this help with Hume’s scepticism about the power of the human mind? • For example, Hume had reasoned that, since it is neither a Relation of Ideas (=analytic) nor a Matter of Fact (=synthetic), the idea of causation as a universal constant is nonsense. • Instead, Hume suggests that causation is just: – co-occurrence of events, which leads to – habitual association, which gives us the – (Illusory) feeling of necessity • Kant’s response: It’s true that causality is not a Relation of Ideas (a logical idea) nor a Matter of Fact (one based on observation). • But it is imposed by the structure of the human mind and so is fundamental to science and human knowledge: it is a Category. Kant’s response to Hume, in more detail: Causation is a Category. • Causation is neither a generalization from experience [a Matter of Fact] nor an analytic truth [a Relation of Ideas], but, rather, a rule for ‘setting up’ our world… • Like a rule in chess, Causation is not a move within the game but one of the rules that defines the game... • So too, for our belief in the ‘external’ or material world…this belief is one of the rules that we use to constitute our experience • The Categories are the ‘laws of experience.’ • Asking why the mind organises raw sense data using Causation, or by any of the other categories, is exactly as silly as asking why a criminal is put in jail. • The answer, in both cases, is the same: “That’s the law.” A consequence of Kant’s Transcendentalism: The Noumenal World • Transcendentalism: the philosophical view that there is a form of knowledge derived from synthetic a priori judgements. • Our knowledge of the world is mediated by the Categories. We only know objects as we perceive them, as ideas. • We can know that there are real objects, because we have sensations of which these real objects are the necessary conditions – they provide the raw material from which sensations are derived. • Yet the world of the real objects cannot ever be known directly, so we cannot know the real objects themselves. • This world of real but extrasensory objects Kant calls the Noumenal World, the world of 'things in themselves', the pure state of things’ being. • Because the human mind structures the universe it perceives, we can never perceive the raw data of experience, by defnition. The Phenomenal World • The world of perception, of subjective sense data after it has been conditioned by space and time and organised and structured by the mind’s categories, Kant calls the Phenomenal World. • This is the world in which humans live and of which they have knowledge. • “[W]e indeed, rightly considering objects of sense as mere appearances, confess, thereby, that [the appearances] are based upon a thing in itself, though we know not this thing as it is in itself, but only know its appearances, namely, the way in which our senses are affected by this unknown something.” [Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics] • So we can only know the world as it appears to us, not as it is in itself. Some issues with Kant’s Conceptual Scheme and the division between Noumena and Phenomena: Isolation, Solipsism… • Order and structure do not exist “out there” in the noumenal world. (For all humans know, the noumenal world might as well be Heraclitus’s formless flux: 'Fire is in all things'.) • Order and structure for humans exist only in the phenomenal world of the human mind. • Yet humans can have no knowledge of “things in themselves”. In a way, we are forced into Kant’s conceptual scheme, cut off from the real, the noumenal. • And can we be sure that each human mind organises and structures the raw sense data of the noumenal world in the same way, by means of the same categories? • Might it not be that each human being creates his/her own individual and unique phenomenal world? We are all in prisons of our own creation… • Kant naturally asserts that all minds must of necessity use exactly the same perceptual categories… So: Kant in a nutshell • Some problems of empiricism helped: he explains how we possess highly abstract concepts, and places the human mind at the centre of everything. • A key notion of rationalism defended: we do have innate ideas, as these innate formal structures are necessary conditions for perception and explain perceptual coherence. • Some problems of rationalism helped: the role of a priori knowledge is clarified and the role of wholly certain statements explained. • However: distance between perceiver and world entrenched. • Phenomenal world seen through perceptual, cognitive structures • Noumenal world: things in themselves inherently mysterious, theoretically unknowable. • Permanent veil of perception theoretically necessary. • Key question, after Kant: “If these principles are grasped a priori, then do they track the way the world is, or just articulate the way the world is to me?”