Citizenship, education and the case of Finnish Roma

advertisement

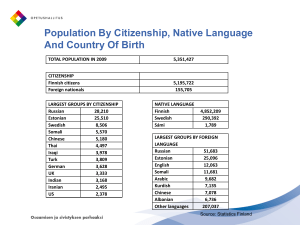

Boundaries of Citizenship – the Case of the Roma and the Finnish Nation-State © Camilla Nordberg 2008 Swedish School of Social Science University of Helsinki Emerging policy agenda Reason to consider the 1990s as the decade in Finland when debates on multiculturalism and the particular needs and rights of minority ethnic groups clearly escalated on the public agenda: increasing immigration & the internationalisation and judication of Finnish politics Triggered a political debate on the multicultural society Minority ethnic groups in Finland Swedish speaking Finns (300 000) The indigenous people, the Sámi (4 000 - 7 000) The Roma (approx. 10 000) Small Jewish and Tatar minorities (approx. 1 000) The Russian minority (the old minority, approx. 5 000) In- and out-migration Large population movements in the 1860s and in 1960-70 During the 1960s and 1970s other Western European countries attracted labour migrants but the Finns moved to Sweden and North America to search for a better life Only during the last twenty years greater relative numbers of refugees and asylum-seekers (more than 600 per cent increase since 1989) Inflows of foreign nationals as a percentage of the total population, 2004 (OECD) Foreign citizens in Finland, 1980-2006 StatFin 2007. The number of foreign born citizens was approx. 180 000 in 2005. Foreign citizens in Finland by nationality, 2005 Citizenship and its boundaries The three ’gates’ of citizenship: Territorial access Citizenship status (incl. denizenship) Substantial citizenship The case of the Roma Long history of oppression Roots in India - left for Europe over a hundred years ago To Finland in the 16th century - harsh policies and systematic assimilation Still in the 1960s the best solution to the social problems of the Romani minority was seen as the extermination of he culture, e.g. by children’s homes The approx 10 000 Roma (Gypsies) of Finland belong to the Kaale (Kàlo) group History to be interpreted in the light of social and human transformation Continuous need to define the boundaries of citizenship The Roma - continuous position on the margins - yet not isolated Each and every grown up Finn, if you ask them to tell you something unpleasant about Roma, they all have a story. Every single one has a story. If you ask all of them, to tell you something nice about the Roma, it might be, that every fifth says, that yes, Hortto Kaalo was a great band. The citizenship frame Exploring the citizenship of Roma in contemporary Finland; citizenship understood broadly as the relation between the Roma and the nation-state Citizenship as an exclusive and excluding category; also citizens with a full citizenship status may experience exclusion and non-participation (e.g. Lister) Rooted in the regime of the nation-state Data Four different studies of ‘claims-making’ Parliamentary debate (top-down perspective) Interviews with Romani activists (bottom-up perspective) Newspaper stories (top-down and bottom-up perspective). Romani activists and majority elite claimsmakers Taking position Citizenship as claims-making ‘collective action which mobilises political demands into the public domain’ (Statham 2002) Citizens not solely objects but agents Citizenship defined in the interaction between actors, structures, institutions Questions of the day What image of the Finnish nation-state is then constructed by the different actors? In which way has the national culture enabled or constrained certain claims? Dimensions of citizenship in activist interviews To be a Finnish citizen To be excluded To be a Rom Also other identities emerged (being a woman, nurse, son etc) Narrative perspective None of our identities is always present – they are activated in specific situations To be a Finnish citizen The primary group identity on the level of the nation-state is that of being a citizen citizen: member of a political community, state (civic participation) national: member of a nation-state, people (belonging) National attachment Well, now immigrants arrive and we who have been here for over 500 years /…/ we are Finnish, we speak Finnish, the Finnish culture and all the rest is ours, we’re a part of this. We’ve got the same religion, which is very important. National attachment I am completely against it [a Roma Nation]. It confuses the whole agenda of minority politics, because it is a completely different thing to talk about a Romani minority than a Roma nation. /…/ when I consider that the Finnish Roma identify with the Finnish society and /…/ if we start to push through such an idea, that we are a nation, then we will soon be building our own territory. National attachment I guess when you see a person in need [Romani asylum-seekers], you don’t just pass her like that; it works on the individual level. But then, when it comes to, say, state politics. Look, as we don’t know these people better than the Finns, it’s not obvious that some people belong to the Romani community. Because in the end, we might not have anything else in common than the awareness of the ethnic identity, but it might be that we don’t have much in common at all. National attachment The Roma do not constitute their own particular group next to the Finnish people but... ...constitute part of Finnish identity Civic attachment When I have done my duty and worked for this Finnish society and paid my taxes, I feel that I have met the requirements set by society, I have done my military service and served this state in accordance with public law and so on. So, should I be given the right to be a good Finnish citizen regardless of the fact that I am a Roma, who has a different ethnic background? Or what is the criterion - are you a good Finn? Civic attachment The Roma /…/ take a very active part in NGOs and in the parishes, and just think about the care work they do for their old people and their children. It is the kind of work that is not noticed or valued by the rest of the society, and is at least not measured in any way. Civic attachment In Finland a strong normative understanding of the intrinsic value of paid work. Paid work has not only been a source of income but also a measure of social competence. The weak labour market position of certain groups does not only lead to a weak economic position but also to a low social status (e.g. Forsander, Weber). While the participants are strong supporters of Finnish society, they also try to raise a slightly broader understanding of societal participation Feminist critique: The devaluation of care-work stressed in traditional citizenship The political meaning of motherhood - the education and caring of the young is part of political life (Lister 2003; Pateman 1989; Siim 2000). Traditional role differentiation within Romani culture Iris Marion Young The bourgeois world instituted a moral division of labour between reason and sentiment, identifying masculinity with reason and femininity with sentiment, desire, and the needs of the body. Extolling a public realm of manly virtue and citizenship and independence, generality, and dispassionate reason entailed creating the private sphere of the family as the place to which emotion, sentiment, and bodily needs must be confined. The generality of the public thus depends on excluding women, who are responsible for attending the private realm, and who lack the dispassionate rationality and independence required of good citizens. (Young 1997: 258) Excluded – socioeconomic dimension We are not really inside this society, /…/ of course, basically we are, but looking at any field of life and comparing for instance Finns and Roma, then no doubt we are much lower than others. I talk about education, work and all different kinds of problems that emerge in life… Excluded – socioeconomic dimension But in my opinion there is a clear justness and the Roma can certainly not complain about that, but in a way we are in a sort of social trap; these differences between the rich and poor have grown, and since we live in this kind of consumer society, in a way we can no longer cope with as little as earlier. So in one sense the lives of the young ones, those who don’t have a job or an education, for example, their lives are limited to a minimal, narrow area/.../ So psychologically it can sometimes be quite hard/…/but I think/…/from time to time we can also be content with how things are here in Finland; here people at least have roofs over their heads and bread on the table and so on as long as they have done the right thing. Excluded – symbolic/cultural dimension When I began my studies, I was far in my twenties, I already had children and everything, and it was extremely difficult for me, I thought, oh my God, what is this, when I speak Finnish and these people speak Finnish, but I don’t, like, get a thing, I somehow don’t understand, that everything, like the literature and all this, it was extremely difficult, because I had to do a duplication of work, because I translated it to my own language, not exactly to Romani, but to this my own Finnish language, because the Finnish that we speak, it is different from the language used by the majority, and it is of big importance. Excluded – emotional dimension To already as a child be aware of the fact that in a certain way you are wrong/…/ And even more so if you haven’t got a solid home, background support, it doesn’t have to be only parents, it can also be a teacher, an adult or so who infuses a strong and sound self-esteem into the child. A person easily gets stuck in the mould that is cast for him or her. You start to put into practice these people’s – what should I say – these people have decided that you are a certain kind of person, then a great deal of strength and courage is required in order to show them that ‘hey, I’m not like that, what you assume me to be’. Excluded – emotional dimension – discriminated citizenship I get extremely annoyed... Like when I go shopping or just spend time, like most people sometimes do. So, immediately I have a swarm of guards behind me. I am walking there like some criminal. At that point one really thinks that this is so hard, and it is really wrong, and that it really violates my fundamental rights. But, to us, it is somehow builtin. Perhaps we too often accept that, that we don’t really /…/ although we might say that ‘this is wrong’, that ‘you can’t act like that’ and that ‘this violates my rights’, but then we don’t really, so strongly, believe that this actually is the case. Yet.... In the beginning of February, we got this new and unique Act on Equal Treatment. When we also find some good models for implementation I do think that we will be able to eliminate such injustice in society. And personally I really think it will open many doors. So, when it comes to legistlation I am quite satisfied. To be a rom - community You know that in your own culture, among those people, there you know all the norms and ways to act and be, so then after all it is quite hard then when you are in a completely different cultural environment, when you’re not familiar with the norms and those things, then it is exhausting in another way. When you are among your own people you feel comfortable. To be a rom - community Well, the status or position of a Rom is rather based on how you get on in life, how you care for your home and for your family, all those things... Those are the first things in life, and then - of course wisdom is valued - but this kind of theoretical wisdom, it is like ’ this man has studied himself insane’ To be a rom - community ….that families now live their own lives, one family here and one family there, and that children no longer have this close connection, for instance to other Romani children /…/ There is a risk that if this strong support and security provided at home no longer exists, /…/ we fall through the safety net and end up in no-man’s-land, if these our own roots are not there. To be a Rom – community When the societal culture is exclusionary, Romani culture provides an important sense of belonging and security, particularly compared to many other marginalised individuals. Next to the communitarian identity, the dilemmas and challenges of a more political minority identity emerges from the material Are group rights beneficial? To be a Rom – minority I don’t accept the idea that some group is strongly supported just because it represents a particular ethnic group, regardless of its history… To be a Rom – minority And now, there was this new directive from the Ministry of Labour concerning the improvement of employment for only Romani people, whatever that will bring about. But I think this is quite bad somehow, that if everything must be regulated by law, it will also take people to an unequal position, wouldn’t it? Thus, when my rights are granted through special regulations, although both of us are Finnish /…/ It is good that there is a period of transition /…/ but of principle I don’t necessarily find it that good… To be a Rom – minority ….like those sewing courses, certainly, someone might even get a profession because those costume makers are needed /…/ but considering this development, well, it is perhaps not the best way to promote change, which inevitably is coming and happening, yet I still see those courses directed to Roma as good, since the threshold is so huge for many, even if they want to study, they don’t really dare to go to those majority… because they feel this inferiority. To be a Rom – minority Also majority children have the right to learn about the minorities. I don’t understand why information about Finnish minorities is not yet included in teaching materials /…/ It is very tough to circulate in every single Finnish school and talk about basic things. To conclude The benign category of the welfare state The ‘good state’ The history of oppression a constraining element for citizenship claims-making? Consequence: claims for group specific rights and socioeconomic justice quite rare Challenges to welfare state legitimacy How far can the particular needs of minority ethnic groups be neglected without creating too wide social gaps? One of the basic principles of the Nordic welfare states has been to prevent too big differences between different citizens. How far can group rights be developed without threatening the traditional universalism of the welfare state and without the majority experiencing a decreasing sense of community/solidarity with an increasingly heterogeneous population? It may then become reluctant to finance the redistribution of resources? (Brochmann & Hagelund 2005) Challenges to welfare state legitimacy Bhikhu Parekh makes the following statement about social justice: The argument being that the welfare state is only possible if we all have a sense of solidarity. Well historically there is very little evidence for this. Welfare state arises for a variety of reasons. We share certain common interests. We don’t have to share common values beyond a certain point … It’s a collective insurance (Parekh 2003, 5). Finnish context Strong social citizenship, weaker cultural citizenship Tolerance and acceptance of difference have been key words – not necessarily imply active measures – the role of outsiders? Lepola (2000) From Foreigner to Finlander: ‘In the scope of a multicultural ideal, social democratization is primarily protected, and only to some extent political democratization and to a minimal extent cultural democratization’ ‘Immigrants are immigrants, there is nothing strange about that, but we Finns, we are Finns’ (Lars D Eriksson) The dilemmas of a politics of recognition Young (1997) Group specific rights for oppressed groups to undermine oppression Critique against Young’s allegedly essentialist stance on collective identities as a prerequisite for a politics of recognition (e.g. Benhabib 2002). A devaluation of identity-interests and an affirmation of subject positions at the level of multiple belongings do, however, risk losing identification for collective action. Groups that have been oppressed and marginalised for a long time cannot escape their economic predicament ‘unless they feel convinced that this is not their fate or natural condition or all they are worth, and that it is within their power to change it’. (Parekh 2004) Lister (2003): Rights, respect, voice Fraser (1997): while marginalisation entails symbolic as well as socio-economic exclusion, its prevention requires both recognition and redistribution, and these cannot be separated. Measures in Finland (examples) Cultural recognition Constitution: the right to maintain and develop Romani language and culture School legislation: teaching in Romani Day care legislation: the recognition of linguistic and cultural backgrounds and the support of these together with the respresentatives of these cultures Yleisradio: services in Romani Political representation and participation The Delegation on Romani Affairs Regional Delegations Participation in the development of educational strategies through the Directorate of education Dialogue Promoting cooperation: contact persons Teacher training Yet... Multicultural citizenship (integration without losing one’s own culture, group rights) or Cultural citizenship (full participation in the national culture and in the formation of this culture and its people) • • • Do not exclude one another, but is the ideal of multiculturalism enough? Multicultural policies and group rights in practice: Who can represent a specific group? Those belonging to a majority usually choose their representatives on the basis of political preferences... No group is homogenous, be it a majority or a minority… Cultural citizenship A way out of the tension within identity politics is to emphasise not the identity categories as such but the process or practice of struggle and claimsmaking, a form of cultural democratisation Active measures to fully include stigmatised identities: anti-discrimination practices, the promotion of multiple representations in the public sphere as well as the recognition of different narratives and identities within public institutions. (Pakulski 1997, Stevenson 2003) Nick Stevenson (2003: 152-153), on cultural citizenship [We] can only promote dialogue in conditions where we have begun to realise the cultural complexity of different positions and viewpoints. This requires not only that we empower ‘minorities’ within public conversations, but that we also seek to understand the social processes that have historically promoted some views over others. The recovery of the ‘other’ and wider questions of justice remain essential to inclusive forms of citizenship. The key word here is respect, not tolerance. To respect ‘the other’ supposes a level of engagement that goes beyond mutual indifference. Literature Brochmann, G., Hagelund, A. (2005) Innvandringens velferdspolitiske konsekvenser: nordisk kunnskapsstatus, Oslo: Nordisk ministerråd. Fraser, N. (1997) Justice Interruptus, London: Routledge. Lepola, O. (2000) Ulkomaalaisesta suomenmaalaiseksi. Helsinki: Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura. Lister, R. (2003) Citizenship: Feminist Perspectives, 2nd edition, Basingstoke: Palgrave. Marshall, T. H. (2000) Citizenship and Social Class, i: Pierson, C., Castles, F.G. (red.), The Welfare State reader, Cambridge: Polity Press, 32-41 Nordberg, C. (2007) Boundaries of Citizenship: The Case of the Roma and the Finnish Nation-State, SSKH Skrifter 23, Swedish School of Social Science, University of Helsinki, Helsinki: University Press. Parekh, B. (2004) Redistribution or Recognition? in: May, S., Modood, T., Squires, J (red.), Ethnicity, Nationalism and Minority Rights, Cambridge: University Press, 199-213. Ruhanen, M, Martikainen, T. (2006) Maahnmuuttajaprojektit:hankkeet ja hyvät käytännöt. Väestöntutkimuslaitos Katsauksia E 22/2006 Stevenson, N. (2003) Cultural Citizenship: Cosmopolitan Questions, Maidenhead: Open University Press. Young, I.M. (1997) Polity and Group Difference: a Politics of Ideas or a Politics of Presence?, in: R.E. Goodin & P. Pettit (Eds) Contemporary Political Philosophy, Oxford: Blackwell, 256-272