Institutions - michau.nazwa.pl

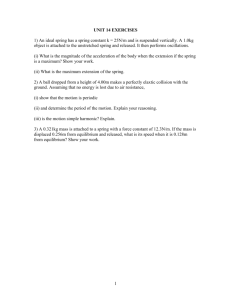

advertisement

Joanna Tyrowicz Game-theoretic approach Institutional Economics Questions People say:“institutions matter.” Great! But, if institutions are nothing more than codified laws, organizations and other such explicit, intentional devices, why can’t badly-performing economies design (emulate) “good” institutions and implement them? Cause they do not change so easily ... How do institutions change? Or, why do they not change as people might like? An answer depends on what institutions are. The sense in which “history matters” for development. 2 In what sense can “history matter”? Specification of institution-free rule of the game is not possible Where do the rules of the game come from? Inevitable infinite regression toward historical past... 3 In what sense can “history matter”? A domain is conditioned by The „function of consequence” is conditioned by mental states and acquired competences of players may comprise organizations as players. technology, statutory laws, and institutions in other domains. History matters in all these. Statutory law is not by itself an institution, unless the enforcer of the rule of law is believed to have the ability and motivation to enforce it. /North and alike would call this dichotomy formal/informal/ 4 In what sense can “history matter”? The selection of an equilibrium (an institution) out of possible many may be conditioned by dynamic linkages of various domains /path dependence/ Overall institutional arrangement may be coherent, reinforcing, diverse across economies, Pareto-suboptimal (not Pareto-rankable). 5 Conceptualising institutions somewhat differently... We would typically call the institutions… the humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic and social interaction informal constraints (sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct), and formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights) rules of the game …but the question is, where do these rules come from??? Face it: anthropology, sociology, history, religious studies, etc. do not take us anywhere within economics! Can we have any ECONOMIC idea for understanding it? Schedule for today: Game-theoretic approach 6 Recent Literature Douglass North, Understanding the Process of Economic Change, CUP, 2005. Avner Greif, Institutions: Theory and History, CUP Gerald Roland, Fast-changing and Slow-changing Institutions, (mimeo) M. Aoki, Towards a Comparative Institutional Analysis, MIT Press, 2001 => TCIA 7 Alternative game-theoretic concepts of institutions Game form: The unit of analysis: Set of players & activated sets of action choices = the domain; The rule of the game: the consequence function which maps the domain to the range of physical consequences (its composite with the utility functions = pay-off functions) What are institutions? Players (=organizations)? Nelson (ICC 1994) Rule of the game (exogenous constraints on the domain/consequence function: law, social norms, etc.)? North, Williamson Equilibrium outcome? Young (1998), Aoki, Dixit (2004) Synthesis of all plus values? Greif (2005) 8 Institution as a Nash Institution is a summary representation of invariant and salient features of a (Nash) equilibrium path, held as shared beliefs of the players about how the game is being repeatedly played. 9 Why so? Criticism and defense Who specifies the game? No game has been specified yet! Anything’s possible! Why impose Nash equilibrium? Well, it’s not particularly demanding… …plus it allows self-enforceability! How do you know if it’s efficient? Who said the rule was “efficiency”? Nash equilibrium doesn’t necessarily imply Pareto optimality, which is not efficiency yet! 10 Why so? Criticism and defense People may believe about many things and be unable to communicate clearly, what is it exactly that they believe Word “beliefs” stands more for expectations and these do not need to be communicated, while they can be updated! If it’s equilibrium, why would it change? Well, most equilibria are not everlasting It’s the transition that exhibits equilibrium properties and not the end point! 11 MASAHIKO AOKI - INSTITUTIONS JOINTLY CONSTRUCT GAME STRATEGIES ENABLE INSTITUTIONS EQUILIBRIUM LIMIT SUMMARISED CONFIRMS ENDOGENOUS RULES OF THE GAME BELIEFS COORDINATE DOMAIN OF THE PLAYER DOMAIN OF THE GAME 12 Dualities in this formulation Endogenous exogenous? Objective subjective? Enabling constraining? Examples to understand better Observing the speed limit Being faithful to your partner 13 Institutional arrangements as equilibrium linkages Complex over-all institutional arrangements evolve, as various domains economic, 2. social, 3. political and 4. organizational => They become linked/inter-related in an equilibrating manner 1. There are two types of equilibrium linkages: complementarities linked games 14 Primitive domain and proto-institutions Repeated economic exchanges Trust, gift exchange (Carmichael & MacLeod) The commons Customary rights, tragedy Asymmetric cooperation Asymmetry in complementarity between residual rights of control and effort → integration of property rights in physical assets and hierarchy (Grossman & Hart). Symmetric cooperation Free-riding? 15 Social exchange domains Non-economic goods/bads social symbols, languages, etc. that would directly affect the payoffs of recipient agents, such as esteem, sympathy, approval, accusation and so on, they are unilaterally delivered and/or traded with “unspecified obligations to reciprocate” are sometimes accompanied by gift-exchanges. Expected surplus from repeated exchanges may be conceptualized as “social capital”. 16 Social-embeddedness and bundling Social-embeddedness On one hand, values and norms may be perceived as exogenously given by individuals but actually they are endogenously shaped by them, “in part for their own strategic reasons.” On the other hand, agents in markets and organizations in modern society generate trust and discourage malfeasance by being embedded in “concrete personal relations and structures (networks).” (Granovetter) Examples: Community of traders Community norms in the use of commons, professional reputation in open software development, etc. 17 Social-embeddedness and bundling Bundling Bundling by an internal player /REMEMBER TCE …/ Bundling of multiple contracts → factory, multi-vendor subcontracting system, venture capital, linked contracts. Bundling by a third party player. The Law Merchant, markets under the rules of law, contingent governance of (symmetric) cooperation (team) by the third party as the budget-breaker Note that the third party itself is a strategic player. 18 The state in political domain What is the political domain? Elections or policies? How are they interrelated? The state as an equilibrium with the government (a third party) as the property rights enforcer cum tax collector → “the fundamental dilemma of the political economy” (Weingast). What kind of political domain? Democratic, corporatist, collusive, developmental, delegated bargaining states Recall Polish land reforms – discussion about the institutional change, was it pro-efficiency or was it through bargaining? Does it really matter for policy implications? 19 Institutional linkage of domains (1): linked games Games are „linked” if one or more players choose strategies across more than one domain in a coordinating manner Because of possible externalities created by such linkage, a behavioural pattern that would be unsustainable in a single domain may become sustainable across many and becomes a viable institution For example punishment mechanism may become selfenforcing even if players are short-sighted and/or nonexcludable in a single domain 20 Institutional linkage of domains (2): institutional complementarities U(x’) - U(x”) increases on domain X for all the players when z’ rather than z” prevails in domain Z Note that it does not require that U(x’) - U(x”)>0 Then x’ and z’ (alt. x” and z”) complement each other → institutional complementarities Codetermination + corporatist state, life-time employment + main bank system 21 Institutional change Internal dynamics of game induces changes in parameters of the domain (skills, technology, etc.). With environmental changes, sub-optimal mutant strategy becomes viable and/or the experiments of new strategies are triggered. The sets of activated choices expand. When new strategic choices converge to a new equilibrium, a new institution emerges. Its characteristics are conditioned by the dynamic linkages of domains. The selection of an equilibrium out of possible many may also be influenced by predictive beliefs by “entrepreneurs” and/or normative beliefs of charismatic leader (as distinguished from “share beliefs), as well as the enactment of statutory law. 22 Reconfiguration of linkage The same social norm embeds different domains of economic transactions over time. Integrated firms → industrial districts. Community norm in the transition to market (Aoki and Hayami) Slow-changing institutions and fast-changing institutions (Roland) Schumpeterian dis-bundling and bundling Dis-integration of large firms and emergence of supply-chain, modular entrepreneurial firms 23 Dynamic institutional complementarities Momentum theorem (Milgrom, Roberts and Qian): Even if the initial level of human resources supporting institution A is low, the presence of complementary institution B may amplify the impact of a policy to induce A. Role of Hong Kong in the China’s market transition Conversely, even if a law is introduced to induce institution A, the absence of complementary institutions B may make its realization difficult. Difficulty of enforcing the market-oriented corporate governance when the rule of law does not prevail. 24 Path-dependence and novelty in institutional change What is the role of path dependence? We are “sticky” by nature (social embededdness) – people like repeating games, so equillibria may be stable What we know limits our ideas of the set of available alternatives (beliefs included), so difficult to come up with a NEW strategy However, innovation (Schumpeterian again!) may come for a number of fairly uncontrollable reasons, changing the dynamics of the game! => NEW INSTITUTION 25