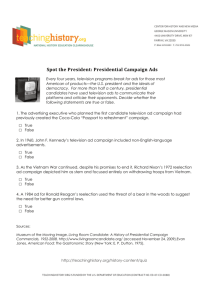

Claibourn, Michele P. and Paul S. Martin

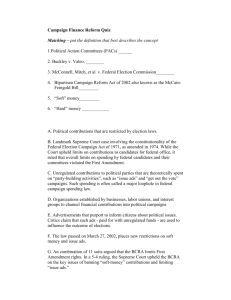

advertisement