From Classical to Contemporary

advertisement

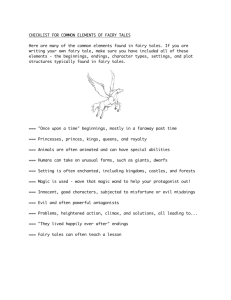

“Tale as old as time” or I’d Rather Not Be Your Guest HUM 2085: Film and Television Adaptation Summer 2013 Dr. Perdigao June 6-11, 2013 Walter Crane’s 1874 Illustration Another Revision (er, parody) • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=diU70KshcjA Reconstructing Gender • Talairach-Vielmas, Laurence. “Beautiful Maidens, Hideous Suitors: Victorian Fairy Tales and the Process of Civilization.” Marvels & Tales: Journal of FairyTale Studies 24.2 (2010): 272-296. • “Beauty and the Beast” highlighting the “bourgeois codes of feminine propriety while at the same time offering their readers a significant perspective on how fairy tales suppress the heroine[’s] agency” (Talairach-Vielmas 274). • “It is probably in the revisions of folktales and fairy tales featuring an animal bridegroom that the models of behavior and incorporated norms and values most reflect how the emerging bourgeoisie stamped their literary fairy tales with the seal of patriarchy. Ironically enough, it is in two rewritings of fairy tales by eighteenthcentury women writers that the pressure exerted on little girls to conform to the model of the sacrificial woman is blatant. When Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont reworked Gabrielle Suzanne Barbot de Gallon de Villeneuve’s ‘Beauty and the Beast’ (1740) in 1756, she manifestly changed the fairy tale into a moral lesson intended for a young, mainly female audience. Mme de Villeneuve’s long romance, published in La jeune amériquaine, et les contes marins, was dramatically shortened by Leprince de Beaumont, who, in particular, cut the long descriptions of Beauty’s entertainments at the palace and the dream sequences in which a prince and a fairy appeared to Beauty to encourage her not to be deceived by appearances” (274). Outsourcing • Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont—stories for children • Her version of “Beauty and the Beast” first published in London where she worked as a governess for fourteen years, and was included in an educational book (274) • Significance of wealth—directed to middle-class readership • “Leprince de Beaumont’s tale demonstrates how the evolution of fairy-tale discourse through the centuries follows the development of the bourgeoisie, gradually setting itself apart from the aristocracy. Her Beast is no starving animal, and the tale suppresses the sexual symbolism of the narrative in order to favor manners, figuring a self-abnegating, submissive, and hard-working heroine, who prefers virtue to looks and is soon rewarded by marriage and happiness—that is, wealth” (275). Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s “Beauty and the Beast” • Rich merchant, six children, three daughters and three sons • Beauty’s favored status • Sisters’ jealousy— “ridiculous airs,” preference for fine things, indulgences: balls, plays, concerts • Beauty reading books • Merchant loses fortune; eldest daughters try to leave; others happy to see pride humbled • Beauty working at home • After a year, father to receive effects; eldest daughters ask for fine things while Beauty asks for a rose • As “Goldilocks” in house • Takes rose The Template • Beauty’s love for father, self-sacrifice • Another Red? Beauty fears Beast plans to fatten her up and eat her • Door—“Beauty’s Apartment” • Large library • Looking glass—sees father • Inner beauty: “‘Among mankind,’ says Beauty, ‘there are many that deserve that name more than you, and I prefer you, just as you are, to those, who, under a human form, hide a treacherous, corrupt, and ungrateful heart.’” • Three months in palace • Asks her to be his wife, but her longing to be reunited with grief-stricken father Returns • Goes to see father but will return after a week • Cautionary tale about those sisters: “They were both of them very unhappy. The eldest had married a gentleman, extremely handsome indeed, but so fond of his own person, that he was full of nothing but his own dear self, and neglected his wife. The second had married a man of wit, but he only made use of it to plague and torment everybody, and his wife most of all.” • Sisters plot to detain her, anger the Beast, and have him “devour her” • Lesson learned (again): “‘Am I not very wicked,’ said she, ‘to act so unkindly to Beast, that has studied so much, to please me in everything? Is it his fault if he is so ugly, and has so little sense? He is kind and good, and that is sufficient. Why did I refuse to marry him? I should be happier with the monster than my sisters are with their husbands; it is neither wit, nor a fine person, in a husband, that makes a woman happy, but virtue, sweetness of temper, and complaisance, and Beast has all these valuable qualifications. It is true, I do not feel the tenderness of affection for him, but I find I have the highest gratitude, esteem, and friendship; I will not make him miserable, were I to be so ungrateful I should never forgive myself.’" The Sense of an Ending • “Beauty scarce had pronounced these words, when she saw the palace sparkle with light; and fireworks, instruments of music, everything seemed to give notice of some great event. But nothing could fix her attention; she turned to her dear Beast, for whom she trembled with fear; but how great was her surprise! Beast was disappeared, and she saw, at her feet, one of the loveliest princes that eye ever beheld; who returned her thanks for having put an end to the charm, under which he had so long resembled a Beast. Though this prince was worthy of all her attention, she could not forbear asking where Beast was.” • “‘Beauty,’ said this lady, ‘come and receive the reward of your judicious choice; you have preferred virtue before either wit or beauty, and deserve to find a person in whom all these qualifications are united. You are going to be a great queen. I hope the throne will not lessen your virtue, or make you forget yourself. As to you, ladies," said the fairy to Beauty's two sisters, "I know your hearts, and all the malice they contain. Become two statues, but, under this transformation, still retain your reason. You shall stand before your sister's palace gate, and be it your punishment to behold her happiness; and it will not be in your power to return to your former state, until you own your faults, but I am very much afraid that you will always remain statues. Pride, anger, gluttony, and idleness are sometimes conquered, but the conversion of a malicious and envious mind is a kind of miracle.’" Anne Tackeray Ritchie’s “Beauty and the Beast” (1867) • Second half of the nineteenth century featured numerous British revisions of “Beauty and the Beast” • “violence of male sexuality” that the woman must tame and accept; education into womanhood (275) • Victorian ideal of “Angel in the House” (281) • Questions about women’s roles in Victorian society • “As Britain changed into an industrial urban economy, the middle classes multiplied etiquette and conduct books that would define clear-cut gender constructions and safely frame the Victorian woman” (280). • Ambivalence between representations of women, works affirming and subverting Victorian patriarchy • Suppresses magic to reflect Victorian reality From Victorian to Contemporary • 17th century literary fairy tale as “interrogat[ing] woman’s place in family and society, as evidenced by the focus on women, most particularly their difficult situations when in the hands of powerful men. Hideous suitors—whether Bluebeards or beasts—increase the tales’ engagement with women’s plight, posting women’s limited choices” (284). • Shift to consider the roles of the heroine in the story, moving the beast into the “background” in Victorian retellings • “Increasingly, the fear of the Beast, of animality and sexuality, are erased. Victorian Beasts are no longer hairy predators. On the contrary, the heroines’ confrontation with male creatures becomes a means of asserting female autonomy and inverting gender roles and expectations. As a consequence, the revisions and transformations of the motifs and plot patterns of classical literary fairy tales serve to question and subvert the dominant socialization discourse meant to be internalized by children and adults through the fairy-tale reading experience. In so doing, they prompt their readers to be alert to the patriarchal interests that lurk beneath innocent-looking fairy tales, like wolves ready to eat little girls when the wander off the tracks of propriety” (290). Alex Flinn’s Beastly • Origins: http://www.alexflinn.com/html/bio.html • “Original”: http://www.alexflinn.com/ • Revision: http://www.alexflinn.com/html/beastly.html • • • • • • • • • • • • • Beginnings Chat room decoded How do they have internet access anyway? The players: Mr. Anderson (Chris) BeastNYC SILENTMAID (but why is she yelling in all caps?) Froggie Grizzlyguy (“Not *that* Snow White”) Thread: “the experience of transformation” Alex Flinn’s Beastly (2007) • Kyle Kingsbury • Became a “prince” • Tuttle • First sees Kendra • English class • As feminist: “Something very wrong when it’s the twenty-first century and the is type of elitist travesty is still being perpetuated” (4) • PE class: “It was a mirror, one of those old-fashioned ones with a handle, like in Snow White” (10) “I noticed for the first time that she held a mirror, the same one she’d had the first day on the benches” (36). Contexts and Subtexts • Magda Rose, idea of beauty; “perfect English,” “I am frightened for you” (25) • Kendra at dance: “Harry Potter Goes to the Prom” (29) • Like character in Stephen King’s Carrie (31) • Curse: “You will know what it is like not to be beautiful, to be as ugly on the outside as on the inside. If you learn your lesson well, you may be able to undo my spell. If not, you will live with your punishment forever” (37). • Reveals self—attractive • • “I have transformed you to your inner self.” “I was a beast” (40). Denial is not just a river… • “This type of thing didn’t happen to real people. It was a dream helped along by seeing the school production of Into the Woods and a few too may Disney movies” (48). • “This isn’t a fairy tale—it’s New York City” (50). Redefinitions • “When I looked back, the hole had healed. I was indestructible, unchangeable. Did this mean I was superhuman, that I couldn’t die? What if someone shot me? And, if so, which was worse—to die, or to live forever as a monster?” (70). • His “former” reflection: Kendra’s • “The voice came from the mirror. Slowly, I brought the mirror down” (72). • Repurposed objects: that mirror • Breaking the curse; chat room: reality • CATFISHING! • • • • • Student at UCLA=girl under 12 40-something housewife Old guy 10 year-old girl Police officer When all else fails… • Googling • Beast, transformation, spell, curse • “just to see if this type of thing had happened to anyone else outside of Grimms’ fairy tales or Shrek” (108). • Finds Chris Anderson’s website • “It was probably just some teen group, full of the type of people who liked writing Harry Potter fan fiction” (108). Erasure • Disguise— “I was invisible” (115), gives freedom • “I’ve changed my name. There was no Kyle anymore. There was nothing left of Kyle. Kyle Kingsbury was dead. I didn’t want his name anymore” (122). • What’s in a name? • “I looked up the meaning of Kyle online, and that clinched it. Kyle means ‘handsome.’ I wasn’t. I found a name that means ‘ugly,’ Feo (who would name their kid that? ), but finally settled on Adrian, which means ‘dark one.’ That was me, the dark one. Everyone—by which I mean Magda and Will—called me Adrian now. I was darkness” (122). Metafictionality • Will’s role • New syllabus • Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame • “subversive” by making the priest the bad guy and the ugly guy good (104) • The Phantom of the Opera—not the Andrew Lloyd Webber romantic version • “I wished I had an opera house. I wished I had a cathedral. I wished I could climb to the top of the Empire State Building like King Kong. Instead, I had only books, books and the anonymous streets of New York with their millions of stupid, clueless people. I took to lurking in alleys…” (123) Irony • Halloween: invisibility • “We’re doing a unit on literary monsters in English class—Phantom of the Opera, Hunchback of Notre-Dame, Dracula. Next we’re doing The Invisible Man. Anyway, I thought it would be cool to go as a man who’s transformed into a monster” (132). • Made-up teacher: Mr. Ellison Reconstructing the Scene • “God, I sounded like the Phantom of the Opera” (157). • “Since I’d been with her, I noticed I’d started to talk differently, pretentious and prettified, like the characters in the books she loved, or like Will” (243). • • On The Princess Bride: “It’s okay. I’m a girl. Every girl pretends she’s a princess at one point, no matter how little her life is like that. And I like the idea of ‘happily ever after’” (203). • • Real life vs. fairy tales: “If this had been a movie, one of those chick-flick romantic comedies, there’d be some dramatic scene where I ran to the bus station and begged her to stay, and Lindy, finally realizing how she felt about me, would kiss me. I’d be transformed. We’d live happily ever after” (253). “I didn’t watch these things in the mirror. I just knew. There was no movie ending. There was only an ending” (254). • • “Face it, this is happily ever after, true love like in fairy tales” (294).