Placement disruption and psychological outcomes

advertisement

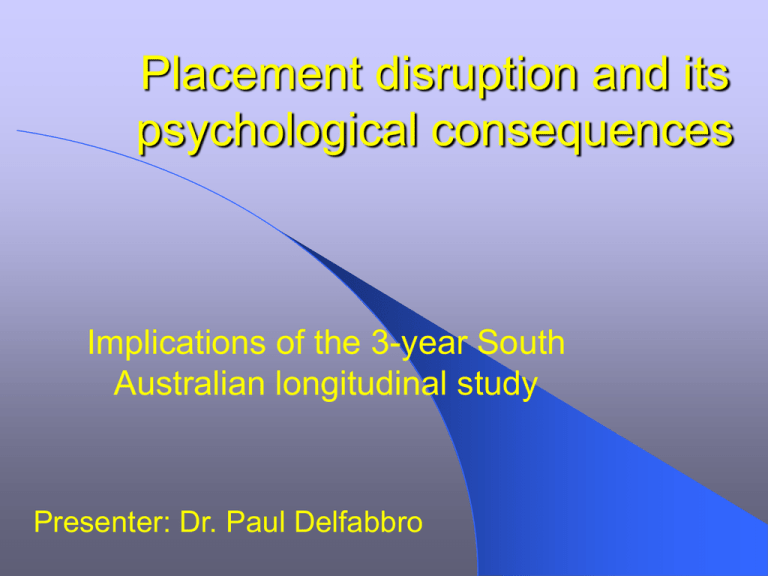

Placement disruption and its psychological consequences Implications of the 3-year South Australian longitudinal study Presenter: Dr. Paul Delfabbro Project team Professor Jim Barber, Flinders University Dr. Paul Delfabbro, Adelaide University Dr. Robyn Gilberton, Flinders University Ms. Janey McAveney, DHS, Adelaide Purpose of presentation Brief overview of the South Australian foster care system and its status during the time of the project Summary of the principal policy and practice directions in Australia Summary of the key findings of the South Australian longitudinal study Implications for policy and practice The South Australian foster care system Heavy reliance on family-based foster care Very little residential or group-care Shortage of families willing to look after adolescents High-rates of ‘placement drift’ Foster care placements are outsourced Policy context prevailing in South Australia Strong emphasis on keeping families together (‘family preservation’) It is assumed that the attachment between children and their biological families cannot be truly replicated by relationships established with other adults Foster care is a necessary evil Little emphasis on adoption But can we generalise from S.A. to other Australian States? The trends and problems identified in South Australia appear to be shared by many other States The research, practice and policy trends identified nationally appear very relevant to S.A. National priorities 1: Evidence Recent edition of Children Australia Emphasis on evidence-based practice This includes a need to monitor children’s well-being as they progress through the care system Possibility of using the LAC system (Sarah Wise’s paper) National priorities 2: Outcomes Achieving more stable outcomes for children in care Better matching of services with needs Developing appropriate standards for foster care services Maintaining family connections (Thomson and Thorpe paper) International context Where might we be headed? In the U.S., much greater emphasis is placed on permanency planning The best interests of the child The Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 The U.S. Adoption and Safe Families Act (1997) Child safety and well-being are now the primary imperatives Emphasis on ‘permanency planning’ Stable and safe arrangements are the 1st priority rather than family preservation In many States, concurrent arrangements for adoption are made at inake Limits are placed on how long children are allowed to drift in care Practice implications of U.S. policies Permanent solutions (Adoption, relative care, or reunification) must be achieved quickly (usually within 15 months) There are fewer rewards for trying to resolve problems in the family of origin If parents are apathetic or unresponsive to goals that are set, they can lose custody of the children within 15 months Financial penalties apply to agencies and/or States that fail to adhere to these guidelines Is this sort of solution appropriate for Australia? Some similar trends are emerging Highly publicised cases of child abuse either in the care system or uninvestigated allegations of abuse in biological families Strong emphasis on child protection (e.g., Layton report in South Australia) Increasing interest in permanency planning (e.g., in Qld) What would make this approach justifiable? Children doing very badly in care High levels of placement ‘drift’ Drift linked to poorer outcomes for children Low rates of family reunification Family preservation not working South Australian evidence: What happens when children progress through the care system? Objectives of study Profile the characteristics and needs of children coming into care Placement patterns, breakdown rates and causes of breakdowns Psychosocial effects of placement instability Identify children most ‘at risk’ Design considerations Longitudinal design to address concerns about cross-sectional analyses Cohort approach: all children included Frequent follow-ups Short and efficiently administered measures Information from multiple sources Mixed methodology Mixed methodology Multivariate analysis of child outcomes Analysis of case profiles / child groups Qualitative review of case histories Interviews with children in care Sampling strategy All new emergency, short-term and longterm referrals (1 week+) between April 1998 and April 1999 Both metropolitan and regional areas Age 4-17 years Exclusions: family reunification cases, remand cases Measurement points Intake 1st 12 months (every 4 months) Thereafter (every 6 months) Interviews with case workers, and a subset of foster carers and children to assess the reliability of measures Sample characteristics 235 children (121 boys, 114 girls) 73% from metropolitan area 40 Indigenous/ 195 non-indigenous 90 (38.%) were teenagers 195 (83%) had a previous placement history 40 (17%) had never been placed in care before Measures Abbreviated CBCL, health, substance abuse, sexualised behaviours, educational and social adjustment, offending behaviour Placement movements: duration, location, nature, reason for termination Family contact Case worker involvement Two identifiable baseline clusters CLUSTER 1 N=132 More girls Mean age =13.35 yrs. Behavioural problems CLUSTER 2 N=103 More boys Mean Age = 7.44 yrs. Parental problems Neglect Placement histories Previous placement history at intake (%) 25 20 15 10 5 0 1 to 2 3 to 5 6 to 9 Placement numbers 10+ Placement destinations Gone Home At 4 months At 8 months At 12 months At 2 years Stable in Unstable care in care Other 59 (25%) 72 (31%) 92 (39%) 12 (5%) 85 (36%) 90 (38%) 49 (21%) 11 (5%) 92 (39%) 83 (35%) 43 (18%) 17 (7%) 95 (40%) 59 (25%) 50 (21%) 31 (13%) Placement rates over 2 years Mean changes per 4 months 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 4 mths 8 mths 12 mths 2 yrs. Follow-up points Why do placements end? Take the 4-month (most unstable period) 49% of placements only intended to be short-term 18% Broke-down due to child’s behaviour 14% Family reunification 7% Other arrangements secured Problematic examples 4 mths 1 2 3 8 mths 12 mths 2 yrs FFFFFFFF F FFRFFFF FFFFFFF FFFFFFFF CY FFFFFC FFFFFFFF FFFFFFFF FF FF F FCFFHFF FYSISYS H YSYSY F Y YSYSMS YSSSYSY M Identifying challenging children Which children are struggling in care? What predicted the case profiles just shown? ANSWER: 2 or more breakdowns due to behaviour in 2 years Comparative placement destinations Gone home Stable Unstable in care in care Other Total sample 88 (48%) 55 (30%) 20 (11%) (n=185) 23 (12%) Challenging 7 (19%) Group (n=50) 9 (18%) 4 (8%) 30 (60%) Psychological outcomes in South Australian foster care Analyses involved 3 groups Group 1: Stable throughout Group 2: Moderately unstable Group 3: Very unstable Conduct disorder Stable 1 Very unstable 0.9 Mod unstable 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 Intake 1 year 2 years Hyperactivity Stable 1.7 1.6 1.5 1.4 1.3 1.2 1.1 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 Very unstable Moderately unstable Intake 1 year 2 years Social adjustment Stable 3.3 3.2 Very unstable 3.1 Moderately unstable 3 2.9 2.8 2.7 2.6 2.5 Intake 1 year 2 years General trends Children stable in care generally improve or remain unaffected by foster care The most unstable children show improvements in the short-term, but then experience deteriorations in functioning after 12 months Results for the most challenging children (n=50) All adjustment measures poorer at baseline and after 2 years Some improvement in conduct No improvement in hyperactivity and emotionality Decrease in social adjustment Summary of placement findings Placement instability is NOT as severe as indicated by cross-sectional designs Most placement changes are planned Most children are doing well in foster care Approximately 15-20% of children are experiencing severe disruption Placement disruption is not problematic unless it is sustained Thresholds and early detection It is possible to detect problematic cases very early and using system data If At intake: Age = 15 + Conduct disorder items all in ‘frequent’ or ‘often’ range THEN p (breakdown) = 80% in 1st 4 months Further examples If N (breakdowns due to behaviour) > = 2 within 2 years, then P(stability within 2 years) = 8% If the child is not stable by 12 months, psychosocial functioning will deteriorate Significance: Supports the role of indicators to monitor progress Need systematic inake assessment Case terminations need to be monitored Critical thresholds and indicators can be used to ‘flag’ or identify cases at risk Problematic cases could be targeted for early intervention Evidence in support of American model? Placement instability appears harmful beyond 12 months Monitoring outcomes is feasible and worthwhile Interventions with families should occur sooner rather than later Is foster a ‘necessary evil’? Children’s views Interviews were conducted with 100 children (50 in the current study and 50 in existing long-term placements) In both groups, 95% believed they were well treated by their carers, and felt safe and accepted Further conclusions Foster care is a good option for many children and most carers are doing an excellent job Foster care should be seen as a realistic option that can benefit children; not simply a last resort We strongly endorse the need for monitoring and early detection of children for whom foster care is not working We believe that this monitoring and early detection process is very feasible Continued…. Prescriptive foster care (one rule for all) ignores the fact that there are different clusters of children in care Certain children are not suitable for family-based care. Other options should be sought for them We endorse permanency planning, but believe that this can be achieved without severing family ties Alternatives to foster care should only be considered when there is evidence for genuine disruption and instability Continued… The same rules should not be applied to children who seem to be doing well in care Foster care should not be a one system fits all The focus should be on what works rather than rigid inflexible policies that are not adaptive to differences within the care system, e.g., carer classifications Other issues examined Predictors of family reunification Nature and effects of family contact Geographical distribution of placements Cost-analysis of special loadings Children and foster carers’ perceptions Follow-up information paul.delfabbro@adelaide.edu.au Personal home-page for reference list (www.psychology.adelaide.edu.au) Australian Centre for Community Services Research (ACCSR) Contact: priscilla.binks@flinders.edu.au