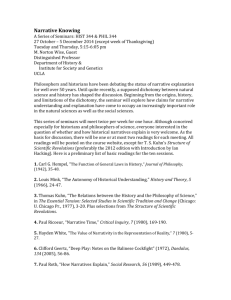

Workshop 2 (slides)

advertisement

Narrative Innovations, Prato 2012 Narrative Innovations Workshop 2 Narrative Styles and effects Corinne Squire, Centre for Narrative Research, UEL http://www.uel.ac.uk/cnr/ Narrative analysis Analysing narrative syntax, semantics and pragmatics: structure, content and context (Mishler, 1986) Yolanda: on being HIV positive in the UK at a time of social service cuts, while being an asylum seeker. Yolanda herself has ‘indefinite leave to remain status. She says she is now ‘empowered.’ She is in her 50s, originally from Zimbabwe, takes ART, and has a number of serious health problems Yeah it is very hard, because you don’t know what to say to someone about their problems, what they are going through. Because some have got relatives who are dying, children who are dying, they can’t go home, they are still grieving here. They are dealing with people’s issues, it is difficult, it is difficult. I can put myself in that position. I’ve got a friend who is dealing with that same issue. She went through, she is going through a lot, she is now depressed, yeah. Sometimes I will go to their house, sleep over, two days or three days, yeah. I will sleep over then I will invite her, I have told her ‘you are welcome to my house, come anytime, if I am not there then my children are there, sometimes I got my grandchildren, ‘feel free, don’t be on your own, yeah, come, I will cook for you – if you want to cook anything, (or) sleep on my bed’ (laughs) yeah, because I know what she is going through, unfortunately, it’s difficult. Narrative analysis Structure: habitual event narrative (Patterson, 2008); parable Content: social support issues; mental health issues; empowerment (Riessman, 2008) Context: told to a friend; a social researcher; a wider community and policy audience; performance of empowered identity (Georgakopolou, 2007; Phoenix, 2008; Riessman, 2008) Interactions: content and structure; content and context; structure and context Some aspects of this story that seem important, are difficult to address within this framework. How does the story do what is such a prominent concern for it: offering help to people living with HIV who are in very difficult circumstances? Narratives’ social style There are some aspects of structure that do not standardly get considered within analyses of structure – though of course, again, they interact with aspects of content and context – that seem to be important in Yolanda’s story and many others. I shall call these social style Social style is a heuristic category including social genres, and narrative ‘figures of speech.’ Social genres (patterns of plot, character and theme) are more general than individual narrative patterns, are not tied to particular datasets, and are not tied to particular media Narrative ‘figures of speech’ are tropes that play a key role in narratives’ progressions. These aspects of social style seem to be important in Yolanda’s story – how, though, might they have effects? Narrative and its effects: social change Narratives can have a range of effects –as well as none – within the field of representation, as well as personally and socially. Many narrative researchers are interested in the relations between narratives and social change. Stories are good at : ‘patching social life together....cementing people‘s commitment to common projects, helping people make sense of what is going on, channelling collective decisions and judgements, spurring people to action they would otherwise be reluctant to pursue’ (Tilly, 2002: 26-7). What are the aspects of narratives that seem to contribute to importantly to narratives' ability to catalyse social change? How do narratives like Yolanda’s do the things Tilly describes? Narrative and its effects: social change How do the social styles of narrative work to generate or support social change? They make narrative associations that call up social connections (revisable linkages) [clear in Yolanda’s story – between her and other HIV pos, and she is then a bridge to her audiences of all HIV statuses] What has connection to do with social change? Iris Marion Young relates responsibility and justice to the processes that connect us with others: ‘some structural social processes connect people across the world without regard to political boundaries’ (2006: 101). Young characterises such social connection processes by five factors: Non-blaming; reference to contextual conditions; orientation towards the future rather than the past, and a collective framing of explanations of the past and of present and future action How can narrative styles potentiate such connection processes? [Yolanda: non-blaming by ref to contextual conditions; collective framing; not the future except insofar as she is actively engaged. HOW does this happen?] What are the social styles that enable narratives to catalyse connection? Narrative styles to look at today: similarisation, familiarisation, physicalisation. Similarisation tropes and genres that work within stories to generate connection within and across HIV differences, through similarity The collective wearing of ‘HIV Positive’ T shirts In my study of HIV in the UK, the language of connection exhibited most consistently was that of narrative similarisation. John is a gay man in his 50s who has been positive since the 1980s. Here, he is describing his current volunteer work with an HIV organisation: John: I think, the, the shock factor is still there for a lot of people,/mhm/I didn’t think it would happen to me,’ and of course now, I mean when I was diagnosed it seemed to be exclusively gay men but now we’ve got mainly heterosexual men and women…So, there’s that sort of shock, horror…well we do get young gay men coming in also, one of their main concerns… is ‘I heard the drugs will make me have skinny arms and legs and a belly’ and all the rest of it…and a lot of them are almost scared to start, um, (antiretroviral) therapy because of what it will do to them/mhm/…It’s alright for me to say ‘well I’m fifty and I look like this’ (affected by lipodystrophy)…because I did look good in my twenties…So I don’t, so I shouldn’t, I don’t (judge), I can understand where they’re coming from… I’m talking to quite a lot of (newly diagnosed people) I suppose, um, yes I find it very interesting really to hear their concerns and to help them, if I can possibly help them at all I can tell them my own experiences and the experiences of friends and that sort of thing… Similarising stories help ‘gather people together’ – in this case, across age, gender, sexualities, national backgrounds, citizenship statuses - into associations that allow for social and political action (Plummer, 1995), through genres of ‘acceptance, ‘coming out’ or ‘speaking out’ that collectivise and emancipate. How general is this narrative style, around HIV? These stories overlap with everyday speech, and you can find them in activist and self-help literature, and in media representations. Might this style be important for other conditions that involve personal suffering silencing and stigmatisation and that generate ‘intimate disclosure’ narratives? (Plummer, 1995) What are the limits of such a style? Narrative similarisation strategies are rhetorics and syntax not of full identity, but of mobile and multiple identifications (Hall, 1990). They are not about total ‘community’ so much as about social associations or neighbourliness President Obama and the (weak) similarising narrative of ‘fairness’: ABC interview PRESIDENT OBAMA: Well-- you know, I have to tell you, as I've said, I've-- I've been going through an evolution on this issue. I've always been adamant that-- gay and lesbian-Americans should be treated fairly and equally. And that's why in addition to everything we've done in this administration, rolling back Don't Ask, Don't Tell-- so that-- you know, outstanding Americans can serve our country. Whether it's no longer defending the Defense Against Marriage Act, which-- tried to federalize-- what is historically been state law.[hesitated because of religious concerns] But I have to tell you that over the course of-several years, as I talk to friends and family and neighbors. When I think about-- members of my own staff who are incredibly committed, in monogamous relationships, same-sex relationships, who are raising kids together. When I think about-- those soldiers or airmen or marines or-- sailors who are out there fighting on my behalf-- and yet, feel constrained, even now that Don't Ask, Don't Tell is gone, because-- they're not able to-- commit themselves in a marriage. Familiarisation Familiarisation relies on a more specific form of connection than similarity: that of biological, familial relationships, or other human relationships that render people part of the same human “family”. The familiarisation strategy of narrative connection uses tropes of family, person, and human within stories, and a narrative genre based on the development or extension of these categories, within which personal and social progression proceeds through the struggle to realise or develop a family-like structure Youth confronting members of the British Houses of Parliament on the day of the reading of the bill to tripe university fees and reduce EMA In my smaller South African study of HIV support, a large number of narratives made familialising connections between people of different HIV statuses – and perhaps most importantly, between people living with HIV. At a time of frequent stigmatisation of HIV positive people, little public disclosure, and almost no treatment access, these narratives worked powerfully to establish commonality between HIV positive people, and t his commonality seemed to ground other forms of change. Phumla, for instance, diagnosed for around a year, was now planning to disclose and educate people in her neighborhood, and narrated her progress towards this point through her support group ‘family’: Phumla: The first thing I noticed there, we are all happy for each other. We treat each other as we are same family born of the same parents. For instance if I say I have nothing at home, one would pop out maybe five rand and say ‘here take it’. If you say that you do not have food at home, no-one will gossip about you. We live like we are children of the same family. That is what I liked. This kind of narrative appears widely in everyday speech, activism, policy and media. In this case, it clearly draws on a recent national tradition of storytelling about the national ‘family’ in relation to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and within the antiapartheid struggle; it also draws on the discourse of ubuntu (humanitiy) Limitations? Familialism within narratives can be conservative and coercive; it also can also skate over important differences. Its strength is its weakness President Obama storying politics through the family ABC interview on same-sex marriage: You know, Malia and Sasha, they've got friends whose parents are same-sex couples. And I-- you know, there have been times where Michelle and I have been sittin' around the dinner table. And we've been talkin' and-- about their friends and their parents. And Malia and Sasha would-- it wouldn't dawn on them that somehow their friends' parents would be treated differently. It doesn't make sense to them. And-- and frankly-- that's the kind of thing that prompts-- a change of perspective. You know, not wanting to somehow explain to your child why somebody should be treated- differently, when it comes to-- the eyes of the law. Press conference on BP oil spill: You know, when I woke up this morning and I’m shaving, and Malia knocks on my door and she peeks her head in and she says, ‘Did you plug the hole yet, Daddy?’ Tied together: Bodily connections There are clearly symbolic strategies within narrative, that produce social connection via a stylistics of the body – symbolisation about the body, or by the body. ‘Tax Wall St Treat AIDS’: ACT UP and Occupy NYC demonstration: die-in at Wall Street, 2012 Tied together: Bodily connections Hydén and Peolsson (2002) identify ways in which bodily speech ties those with chronic pain into effective narrative communication. Gaze and gestures, with words Representing pain on the body Tied together: Bodily connections • Gobodo-Madikizela (2010) analyses how uses of specific bodily metaphors in Xhosa, as well as other words and phrases linked to the body, work within narratives to move them towards forgiveness. For instance, an interviewee used the word inimba, an expression for connection related to the word for the uterus and metonymically the umbilical cord, and connoting the parent’s, particularly the mother's ongoing connection with her child, and emotional connection more generally, to name the difficult-to-describe link she felt with the parents of her own child's killer when she forgave the murderer. • Limitations: Over-strong and over-general metaphorisations of connection Troubles with stories and social change •Narratives' power can function, like other kinds of power, in different directions, “for” as well as “against” social division (Foucault 1980), conservatively or regressively. •Narratives do not always relate strongly to the material world. Frequently, narratives operate outside social functionality; it may not be possible to say what they 'mean', let alone what they 'do' or whether they produce change. Such difficulties often appear empirically, in the incoherent, incomplete, sometimes ineffectual or regressive character of narratives analysed by social researchers (Hydén and Brockmeier 2008; Hyvärinen et al. 2010; Riessman 2008). •However, complexities in narratives' relationship to social change do not obviate the possibility that the relationship is an important one. her mom.She knew that food was one of their most expensive costs, and so Ashley convinced her mother that what she really liked and really wanted to eat more than anything else was mustard and relish sandwiches. Because that was the cheapest way to eat. She did this for a year until her mom got better, and she told everyone at the roundtable that the reason she joined our campaign was so that she could help the millions of other children in the country who want and need to help their parents too. Now Ashley might have made a different choice. Perhaps somebody told her along the way that the source of her mother's problems were blacks who were on welfare and too lazy to work, or Hispanics who were coming into the country illegally. But she didn't. She sought out allies in her fight against injustice.Anyway, Ashley finishes her story and then goes around the room and asks everyone else why they're supporting the campaign. They all have different stories and r easons. Many bring up a specific issue. And finally they come to this elderly black man who's been sitting there quietly the entire time. And Ashley asks him why he's there. And He does not bring up a specific issue. He does not say health care or the economy. He does not say education or the war. He does not say that he was there because of Barack Obama. He simply says to everyone in the room, "I am here because of Ashley." "I'm here because of Ashley." By itself, that single moment of recognition between that young white girl and that old black man is not enough. It is not enough to give health care to the sick, or jobs to the jobless, or education to our children. But it is where we start. It is where our union grows stronger. And as so many generations have come to realize over the course of the two-hundred and twenty one years since a band of patriots signed that document in Philadelphia, that is where the perfection begins.