Text.

advertisement

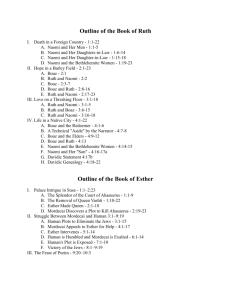

1 A Sermon for DaySpring By Eric Howell “Total Commitment Willingly Given” Ruth 1-4 November 8, 2015 Today’s scripture readings draw us into reflection on the story of a person in the Old Testament who has everything—family, friends, a home, economic security, and then loses it and has to pick up the pieces. Sound familiar? Is that a collective groan I hear from those of us who have just gone through forty-two agonizing chapters with Job, four weeks of wrenching existential examination of good and evil with the man and his friends on the ash heap. Take heart. This is Naomi and Ruth, not Job. When life falls apart for women, they don’t have time for thirty-eight chapters of ash heaps and men’s metaphysical meditations. The women are hurting, but life keeps moving and they keep moving too. The story is really quite delightful. It’s almost like a perfect story the way it is told. Yet like Job’s story, it opens in tragedy. Three women lose three husbands and are left widowed. The women form a kind of triangle with Naomi at the top. She’s the mother, a widow whose husband had brought her and her sons away from her home in Bethlehem because of a famine. They’d immigrated across a river into the neighboring nation, over to Moab to find some work and some opportunity. They must have found some work though we don’t know much about that. What we do know is that their two sons found Moabite women and married them. Shortly after their father died, they died too. Three women bury three husbands. Two women are in their homeland but grafted in the family of a foreigner. One woman is in a foreign land now with two daughters-in-law. It’s a tragedy and a family mess. Naomi says to the girls, “I’m going home. You two stay here. You are released from our family. Go to your parents, marry, and live happily among your own people.” One daughter agrees this would be best. She kisses her mother-in-law and goes to her own home. The other daughter clings to Naomi. “Do not urge me to leave you or to return from following you. For where you go I will go, and where you lodge I will lodge. Your people shall be my people, and your God my God. Where you die I will die, and there I will be buried.” What a beautiful expression of total commitment willingly given. It’s no wonder that many marriages have begun with the same words. When they were first uttered, they were not wedding words on Ruth’s lips, but in them we have seen the 2 commitments that marriage holds sacred. Marriage is an immersion into a new life where your best self and your worst self—your whole self is given in service to the best and worst—the whole of the other. The two become one. They are beautiful words, aren’t they? For Ruth they weren’t said in the best of times, for richer, and in health. They were said in the worst of times, for poorer, and in the shadow of death. They are beautiful words and words of gravitas coming as they do from a woman who knows what it means to suffer and to bury a husband. Ruth knew full well that the pledge to go to another place, and among another people, and among another community would be to a life that was not her own. Her pledge to worship Naomi’s God was to commit to a God that was not her own. And this commitment was for life, unto death. What we know about Ruth is that she is humble and she’s courageous. Ruth is not intimidated by much. She may have nothing to offer to Naomi or anyone else, but she’s willing to offer her whole self. The whole self has always been the measure of commitment, whether in wedding vows or by baptism into the faith. We don’t sign contracts in Christianity, we take vows, we enter covenant. We are immersed. We give as much of ourselves as we can to as much of God as we know (thanks Stephen Shoemaker). We hear courage in the conviction of Ruth’s commitments and see it in her when the odd mother-daughter pair arrive back in Bethlehem and set tongues wagging. Naomi is so down she doesn’t know what to do. All she can mutter is: “I went away full, and came back empty.” That’s all Naomi can see in her grief—her bed is empty, her dining room chairs are empty, her bank account is empty, and her belly is empty. So is her hope. So Ruth gets to work. Unintimidated by hard work or being a foreigner in a foreign land, Ruth goes out to the fields for the only kind of work she can find. Gleaning: joining other poor women who are following the reapers in the fields to pick up stalks of barley they missed or that fell to the ground. She happens to glean on the fields of Boaz who happens to be a relative of Naomi. When bossman Boaz comes around checking on his workers he asks about this new girl. When he learns who she is, he confronts her with hospitality, “Ruth, you are welcome here. Stay on my land to glean. My men won’t touch you; they will protect you. And tonight after the gleaning come and eat with us.” And he told his men, “Leave a little extra in the fields, drop a little more from your bundle for her.” That night, exhausted but with a full belly and heart, Ruth went home and told Naomi everything that had happened. Naomi almost jumped out of her skin: Boaz? 3 Are you sure? That’s wonderful. He’s one of my relatives. He’s one of our redeemers. That’s an interesting word isn’t it? He is a redeemer, speaking of this man Boaz. In scripture, most often the redeemer is God himself. Even Job, feeling abandoned on his ash heap, confesses, “I know that my redeemer lives, and that he shall stand at last upon the earth.” And Isaiah exclaims: As for our redeemer, the LORD of hosts is his name, the Holy One of Israel. (47.4) In the New Testament, the redeemer is Christ himself who came to liberate us from unrighteousness, sin, and separation from God. The redeemer is someone close to you who comes to deliver you from your suffering and plight. In Old Testament times there was an intricate societal order to who had the rights and responsibilities of being a redeemer for those who needed serious help. Somehow Boaz held this role for Naomi’s family, which would usually mean marrying a widowed woman in the family to restore their place in the community and, more importantly, ensure that children could be born to continue the family’s future. Boaz was on the redeemer list, but would he do anything about it? He doesn’t for a long time. But keep it up Ruth. Keep going to his field and let’s see what happens. Let’s see what interest Boaz takes in you. So she went. She gleaned in his fields through the next two harvest seasons, yet what had seemed like a spark at the beginning, fizzled. Boaz protected and provided for her but showed no interest beyond that in her. Or seemed to. It seems that the truth is that he was shy or scared or insecure that a girl as young and beautiful as Ruth would be interested in him. And typical man, he takes no hints, picks up on no signals, and takes no action. So Naomi takes matters into her own hands. You know, sometimes men are a little slow, but women know how to get things done. She gives Ruth instructions. Ruth’s humility and courage are called on again. This time at night. She comes to Boaz in the middle of the night, uncovers the blanket from his feet, and lays there in the dark until he wakes up startled, not expecting to find a person at his feet, much less a woman laying there. “Who are you?” he asks to the dark shadowy mass at his feet. He hears a woman’s voice: “I am Ruth your servant. Spread your wings over your servant, for you are a redeemer.” Let me translate. “Marry me already.” 4 Boaz is, uh, surprised. He can’t believe she hasn’t gone after some good-looking young man, or someone with more money. He’s humbled and touched. “May you be blessed in the Lord, my daughter. You have made this last kindness greater than the first in that you have not gone after young men, whether rich or poor. And now do not fear. I will do for you all that you ask. And now it is true that I am a redeemer. Yet there is a redeemer nearer than I.” Isn’t that a beautiful line? It is true that I am a redeemer. Yet there is a redeemer nearer than I.” It sounds beautifully spiritual. I love you but there is one who loves you more than I. I am your doctor, but there is a physician more powerful than I. It sounds like it should be spiritual. But it is really not. It’s practical. Boaz knows there is a person unknown to Ruth who has right-of-first refusal, redemption rights, in this ancient society. Let Boaz go work that out and then he’ll marry her. He does. It’s not particularly romantic except in a clumsy kind of patriarchal way. At the city gate he approaches the other man. It goes something like this: Mr. So-and-so, Naomi’s family has a piece of land. You have rights. Would you like to buy it? Yes I would, thank you. There’s some fine print: Whoever gets the land, also gets the girl. Do you want the girl? No, I don’t. Well, I do. Boaz comes home to marry the girl. And then this story, delightful on its own merits, sets its heights even higher. Ruth bore a son. Interesting, just as in Job where the attention at the end is more on the girls than the boys, at the end of Ruth, the women gather around and they, not the father, are the ones who name the child, and they say, “A son has been born to Naomi.” Not Boaz. There’s a redemption here not just of economic fortune, but of broken hearts made whole again. The women named him Obed. This would be a nice story if that’s all there was. But there’s more if you see the story telescoped from the future. Obed was the father of Jesse. And Jesse was the father of David. This is the unlikely story of David’s grandfather Obed and his great-grandmother Ruth and greatgrandfather Boaz. Who could have predicted their grandson would be the ultimate insider for Israel’s history. But in his past were total outsiders, women all—Ruth the impoverished migrant farming widowed Moabite who had to knock goodhearted Boaz on the head to marry her. Boaz own mother was Rahab; Rahab the Canaanite harlot who hid 5 Israel’s spies. And back up the family line was Tamar, whose story was both tragic and sordid. All of these are in King David’s lineage which means they are in the human family tree too of Jesus. We might say in today’s language: their blood is in Jesus--a foreigner, a harlot, rejected woman. And that’s just the women. The men include an adulterer and murderer, a philanderer, a polygamist, failures, and many generations of forgettable people. Some people are ashamed of their family. The New Testament has Jesus wear this history like a badge of honor, as if it is something good, something sacred, to have within your being, in your DNA, the complex, fallen, wonderfully diverse scope of humanity. In his very DNA, attested on the first page of the New Testament, we meet Jesus, son of kings and scoundrels, insiders and outsiders, the uninteresting and the unforgettable like Ruth. In Jesus’ nature, certainly in his friendships, all over in his teaching, delightfully in his heritage, so many walls break down: divine and human, power and weakness, rich and poor, insiders and outsiders, life and death, who’s in and who’s out. So maybe that day when Jesus saw the poor widow drop a small coin in the treasury at the Temple, his thoughts were of his own widowed great-grandmother Ruth whose story he had heard from the time he was on his dad’s knee. Maybe he remembered that the impoverished, the outsiders, the overlooked, the marginalized have something important to offer. When you see it like that, you wonder if he wasn’t talking too about Grandma Ruth, when he said: “She put in everything she had. All she had to live on.” Copyright by Eric Howell, 2015