Go to my web page - Accounts Receivable simulation

advertisement

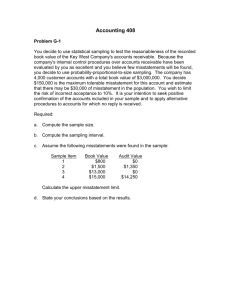

Teaching Notes Education Objectives of the Project The simulation consists of 1,000 customer accounts and it creates a unique sample for each four-digit student ID. Using customer data, the simulation creates confirmations, responses to confirmations, invoices, bills of lading and purchase orders in the form of *.html files which are readable with most web browsers. The educational objectives of the project are: Students understand the confirmation process Students perform alternative procedures for non-respondents Students observe tangible examples of audit evidence Students project sample results to the population Students form a conclusion from their audit procedures Students prepare audit workpapers Availability The following materials are available on the website: http://ar-simulation.com/ The exercise for distribution to students which is the first portion of this paper The complete exercise including the teaching note Copies of last year’s workpapers The Excel workbook which includes the simulation The four templates which must accompany the simulation A PowerPoint introducing the assignment Confirmation responses for n=25 and ID 1234 A list of the discrepancies generated by the simulation Last Year’s Workpapers Last year’s workpapers are included with the assignment for students to use as templates. This is consistent with practice, where auditors typically have access to the prior year’s workpapers. Excel Simulation and Templates Students must be enable macros because the Excel simulation uses them extensively. The simulation calls on the following *.html templates: TemplatePO.html creates purchase orders; TemplateBOL.html creates bills of lading; TemplateINV.html creates invoices; and TemplateConf.html creates confirmations and responses to confirmations. These template files must be in the same folder as the spreadsheet because the Excel simulation will not look to other folders for these templates. PowerPoint files and Confirmation Responses (n=25, ID 1234) The PowerPoint file available on the website enables you to quickly demonstrate the assignment to students by using the following tips. From the website, you can print out the Excel file which lists the confirmation responses for a sample of 25 using student ID 1234. These are the results used in the PowerPoint. This will provide the amounts on the confirmations so you won’t need to actually look at each confirmation and you can focus on the process. When demonstrating alternative procedures, you should be aware that the dollar amount on every purchase order and invoice always equals the book balance and there is a bill of lading supporting every transaction. You shouldn’t tell this to your students, but this will allow you to demonstrate the assignment much more quickly as you won’t need to actually read from the invoices, bills of lading or purchase orders. Each column of the results page of the simulation will auto-fill after students enter five responses. This was done to limit the amount of time students spend on this assignment. 2 Discrepancies The simulation does not have a single solution. While the simulation always generates the same discrepancy for any given customer’s confirmation response, the discrepancies do not flow through to the alternative procedures. None of the purchase orders, bills of lading or invoices contain discrepancies. The purchase orders, bills of lading and invoices are always consistent with the recorded book balances. Project Efficacy Questionnaire During the spring term of 2011, 75 of the 91 students enrolled in our classes responded to the following questions using SurveyMonkey. The table following the questions summarizes their responses. 1. The Accounts Receivable Project provided a more realistic auditing experience than is typical for accounting classes. 2. I enjoyed completing the AR Project. 3. The AR Project complimented the text and enhanced my understanding of the accounts receivable confirmation process. 4. The AR Project complimented the text and enhanced my understanding of what it means to perform alternate procedures for accounts receivable. 5. The AR Project helped me better understand the nature of audit evidence. 6. The AR Project helped clarify the relationship between audit evidence and auditors’ conclusions regarding the fair presentation of account balances. 7. I am more familiar with auditors’ work papers because of the AR Project. 8. The AR Project helped me better understand how the audit risk model is used. 9. I would learn more and be better prepared for an auditing career if I were exposed to more projects like the AR Project. Responses to Questionnaire number of Strongly repsonses Disagree Strongly Disagree Neutral Agree Agree 00 10 10 20 20 30 30 40 40 50 50 60 60 70 70 80 80 90 90 100 100 average (1) 74 2 0 0 0 0 1 2 3 35 13 18 83.1 (1) (2) 75 2 0 4 1 0 3 6 9 24 16 10 74.8 (2) (3) 75 2 0 0 1 0 1 3 7 27 14 20 82.3 (3) (4) 75 1 0 2 0 1 0 4 10 23 13 21 81.7 (4) (5) 74 1 0 2 1 1 3 3 5 25 16 17 80.1 (5) (6) 75 0 0 4 0 0 8 3 12 23 12 13 76.3 (6) (7) 75 1 1 2 1 0 3 3 2 23 12 27 82.3 (7) (8) 75 1 1 4 3 5 6 5 21 11 10 8 67.1 (8) (9) 75 1 1 0 0 2 3 3 3 11 13 38 86.4 (9) 3 Implementation Guidance Many steps in the confirmation process are mechanical. The sample size may be given or determined from a table. The preparation and mailing of confirmations is mechanical. Agreeing information from a confirmation or a bill of lading with a subledger can become rote, if not mechanical. Auditors typically use last year’s workpapers as a template for the current year. Consequently, we must continually warn students that circumstances change from year to year and they must be vigilant and not just blindly follow last year’s workpapers. Prior to using this exercise, confirmation was merely a vocabulary word which our students memorized. They had no basis to reflect on the process. A discrepancy between a recorded balance and a confirmation, or any audit discrepancy for that matter, was a vague concept students had difficulty visualizing. Completion of this exercise enables students to better reflect on the confirmation process and to visualize discrepancies. We assign this project early in the term, after we have covered statistical sampling but before we have covered risk, internal control, audit documentation, or accounts receivable. Intuitively, it may seem ideal to perform the simulation while reading the corresponding material in the text, but we did not find that to be the case. Completing this exercise early in the term gives students a referent as topics are covered later in the term. We continually refer back to this exercise when we discuss risk, internal control, evidence, the confirmation process and audit documentation. We recommend you implement the project in a manner that minimizes both class time and student time. The available PowerPoint slides require about 20 minutes of 4 class time to introduce the assignment. Our students report that the simulation requires approximately one hour to complete. We are not terribly concerned with how many mistakes students make on the assignment. The benefits of the project accrue in subsequent lectures because students have some background when we discuss risk, internal control, evidence, the confirmation process and documentation. We email the assignment to students and attach the first portion of this manuscript, the Excel simulation and the four required templates. Students are instructed to read the assignment and they must be reminded that all four templates must be in the same directory as the Excel simulation. Having previously covered statistical sampling, the simulation reinforces this topic. However, most of the educational objectives relate to the confirmation of receivables rather than statistics. You can simply instruct students to select the desired size sample. We require our students to calculate the sample size necessary to limit the risks of incorrect acceptance and incorrect rejection because we find this provides a framework to discuss these risks. You can add a time dimension to the project by assigning the simulation in stages. Students can complete the first four steps of the simulation, which involves the creation, printing and mailing of the confirmation requests. In order to create a time lag between the mailing of the confirmations and responses, you can wait until the next class to assign step 5. In this step students review the responses and record the confirmed amounts on the results page of the workbook. Wait until the next class to assign step 6 in which students review and record the responses to the second 5 confirmations. Finally, during the next class you can assign step 7 which covers alternative procedures. We remind students that the audit planning document previously established the acceptable level of risk and the tolerable misstatement for accounts receivable. In order to achieve the desired level of risk, every account in the sample must be audited, not just the accounts of the customers who responded to confirmations. You may want to explain the vouching procedure used to perform alternative procedures. We spend minimal time explaining the mechanics of the alternative procedures because our students have previously completed a project in which they vouched entries from a sales journal to invoices, shipping documents and sales orders1. This allows us to focus our discussion on risk. Increasing the sample size does not increase the time necessary to complete the project. Students are only required to complete each procedure five times after which the results page of the Excel simulation auto-fills the remaining entries. For example, once five entries are made in the column for 1st Balances, the simulation auto-fills the remaining entries in that column. The same is true for the 2nd Balance, PO Amt, BOL and Inv Amt columns. We wanted to limit the time students spend mechanically inputting data. We believe five entries allows students to reflect on the documentation of evidence without imposing a significant time burden. 1 Author, 2009. 6 We find it necessary to explain the role of the prior year’s workpapers 2. Many students are concerned that merely updating last year’s workpapers might be cheating or plagiarism. Students use their sample results to conclude whether or not accounts receivable are materially overstated. The simulation helps students see how audit procedures generate evidence which become the basis for their conclusion. Auditing standards state For tests of details, the auditor is required by paragraph .13 to project misstatements observed in an audit sample to the population in order to obtain a likely misstatement. Due to sampling risk, this projection may not be sufficient to determine an amount to be recorded (ASB 2011 AU-C 505.24). … the projected misstatement is the auditor's best estimate of misstatement in the population. As the projected misstatement approaches or exceeds tolerable misstatement, the more likely that actual misstatement in the population exceeds tolerable misstatement (ASB 2011 AU-C 505.27). We require students evaluate their results and determine if the amount by which their projected misstatement exceeds tolerable misstatement provides sufficient allowance for sampling risk. Although standards do not require that auditors evaluate sample results using statistics, statistics does help illustrate the relationship between the sample results and risk. Extension of the Project This remaining material is provided to possibly supplement discussions of statistics, audit risk, internal control, accounts receivable, audit sampling and audit documentation. 2 The spreadsheet in Workpaper 3 can be replicated by having the simulation select a sample of 44 using student ID 1123. 7 Covering Statistics Concurrently with the Simulation Appendix A is a handout if you cover statistical sampling concurrently with the accounts receivable simulation. Appendix A includes a sampling plan based on the AICPA Audit Guide: Audit Sampling. It also addresses each of the issues raised in the sampling plan. Appendix B supplements the statistical calculation in the Workpaper 2. The first portion of Appendix B provides a legend for the terms used in the sample size calculation. The second portion illustrates the use of a hypothesis test to evaluate the sample results. The final section compares the projected misstatement from the sample with the tolerable misstatement and evaluates whether the allowance for sampling risk is adequate. This second approach is consistent with terminology used in auditing standards. Subsequent Discussions of Audit Risk When teaching the audit risk model, we refer to the simulation. We ask students to consider the effect on the required sample size (1) if we had instead taken a primarily substantive approach, or (2) if we had determined internal controls were moderately effective rather than very effective. Subsequent Discussions of Internal Control As the project is written, the audit team previously evaluated the internal controls to be very effective and assessed control risk as low. However, the simulation is seeded with a large number of discrepancies, making it likely that all students will encounter discrepancies. This leads to discussions about the possible need to reassess control 8 risk. The question we pose to students is: “How can we find a significant number of discrepancies if the controls are effective?” We discuss possible causes of the observed discrepancies. Workpaper 3 illustrates two possible discrepancies. The first is an order which was billed even though a portion of the order remained on backorder as of Dec. 31 (see footnote #1 of Workpaper 3). While obtaining an understanding of the billing process, auditors need to ensure the client only bills for goods that have actually been shipped. Otherwise, the auditor may need to extend procedures to audit items on backorder. The second discrepancy involves a sales return which was in transit as of year-end (footnote #2 of Workpaper 3). Because the audit will occur after year-end, the auditor will likely be able to exam returned merchandise. Other examples of overstatements in the simulation could result from: (1) billing customers for sales that did not occur, or at least for sales that had not occurred as of December 31st; (2) billing customers for more products than were actually shipped or billing at higher prices than those on the approved price list; (3) shipping more goods than the customer ordered; and (4) shipping products to customers who never ordered the products. Finally, we discuss controls which might prevent such errors; controls such as having the shipping department verify that a customer purchase order exists for every shipment and that the quantity shipped agrees with the quantity ordered. In the billing department, controls should be in place to verify that a bill of lading exists before an invoice is created and also to agree the prices on the invoice with the official price list. 9 Subsequent Discussions of Accounts Receivable By the time the textbook we use covers accounts receivable our students have a better background about auditing procedures. We again discuss conditions which might explain discrepancies between the recorded balance and a customer’s response to the confirmation. We also explain that auditors do not automatically accept the customer’s response as correct. For such discrepancies, auditors examine source documents to determine whether the amount the customer confirmed or the recorded balance is correct. One method of auditing discrepancies is to vouch from the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger to the invoice, bill of lading and purchase order. This is an opportunity to reinforce that vouching to the invoice provides evidence the customer was billed for the recorded amount; the bill of lading provides evidence the goods were actually shipped to the customer; and the purchase order provides evidence the customer actually ordered the goods. This naturally leads to a discussion of alternative procedures. Rather than vouching to the supporting documents, some auditors might prefer auditing subsequent cash receipts. Subsequent Discussions of Audit Sampling In order to provide a framework to discuss the relationship between the quantity of evidence and the risk of an incorrect conclusion, we cover audit sampling early in the term. Later, when the text covers account receivable confirmations, we refer to the simulation and again discuss the evaluation of sample results. Because this comes toward the end of the term, we discuss possible implications of any material 10 misstatements detected by our substantive procedures. We ask students to consider if it will be necessary to reassess control risk and extend our substantive tests. Although Charles Cabinets is a private company, we discuss the implications detection of material misstatements would have if this were an integrated audit for a public company. For a public company, the existence of a material misstatement would likely result in an adverse opinion regarding internal controls, even if the client agrees to correct the misstatement. Subsequent Discussions of Audit Documentation Our students have difficulty grasping the importance of good audit documentation. By including workpapers, the project exposes students to workpapers. We frame discussions regarding audit documentation in terms of litigation. In case they are ever required defend their conclusion to a jury, we stress that their documentation may need to persuade a suspicious jury that they actually performed the procedures and obtained sufficient evidence. PCAOB inspection reports substantiate the need for proper documentation. A word search of one recent PCAOB inspection report revealed seven instances where the PCAOB found no evidence in the audit firm’s documentation that they had performed a required procedure. Subsequent Discussions of Fraud If you want to discuss fraud in accounts receivable, students can read the article “Detecting Circular Cash Flow” in the Journal of Accountancy (Monhemius and Durkin 2009). This article discusses how companies use receivables as collateral to obtain loans which may create incentive to inflate receivables. It also illustrates the limitations of confirmation procedures to detect sophisticated schemes used to inflate 11 receivables. In addition, the article points out various red flags that may indicate fraudulent activities and helps students understand the need to be vigilant during the confirmation process. Grading Grades in this course are based on 500 total points of which students can earn 25 points for successfully completing this project. The rubric in Appendix C was developed from shortcomings we observed in student workpapers. The rubric is segmented into five equally weighted components: timeliness, the material at the top of the workpapers which is common to all three workpapers, and the procedural material on Workpaper 1, Workpaper 2, and Workpaper 3. Students can earn up to 5 points for each segment. We encourage students to think about what they are doing as they complete the project because many of the procedures and concepts incorporated in the project will be included on the exams. 12 Appendix A Sampling Plan (AICPA Audit Guide: Audit Sampling) The AICPA Audit Guide for audit sampling suggests the following questions be addressed when planning a sampling procedure. “2.30 The following questions apply to planning any audit sampling procedure, whether it is nonstatistical or statistical: • What is the test objective and relevant assertion? (What does the auditor want to learn or be able to infer about the population? What assertions are being tested?) • What is the auditor looking for in the sample? (How is a misstatement or deviation defined?) • What is to be sampled? (How is the population defined?) • How is the population to be sampled? (What is the sampling plan, what is the sampling unit, and what is the method of selection?) • How much is to be sampled? (What is the sample size?) • What do the results mean? (How are the sample results evaluated and interpreted?)” What is the test objective? What assertions are being tested? How is a misstatement defined? How is the population defined? What is the sampling unit? What is the sample size? What is the method of selection? How are the sample results (to be) evaluated? What do the results mean? Determine whether the accounts receivable balance is materially overstated. Materiality is defined as 10% of the accounts receivable balance. Existence; valuation and allocation When the audited value for a customer’s account as determined by confirmation or alternative procedures does not agree with the amount recorded in the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger All customer accounts included in the accounts receivable subledger, which has been agreed to the general ledger balance Customer accounts in the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger Must be determined Random sampling Send positive confirmations to selected customers Perform alternative procedures for customers who do not respond to confirmation requests Perform a hypothesis test to statistically generalize the sample results to the accounts receivable balance. Conclude on whether the accounts receivable balance is materially overstated 13 Appendix B Sample Size calculation $2,371,983.60 BV book value $2,550.52 ̅̅̅̅ 𝐵𝑉 average book value $237,198.36 TM tolerable misstate $255.05 ̅̅̅̅̅ 𝑇𝑀 average tolerable misstate $2,134,785.24 BV - TM $2,295.47 μ = ̅̅̅̅ 𝐵𝑉 − ̅̅̅̅̅ 𝑇𝑀 hypothetical mean 806.81 Sx standard deviation Sx/√n std error of the means 930 items in population 0.30 risk of incorrect rejection 1.04 Zα/2 number of std dev 0.15 risk of incorrect acceptance 1.04 Zβ number of std dev ̅̅̅̅ 𝑇𝐸 = Zβ* Sx/√n + Zα/2* Sx/√n (Zα ⁄2 √𝒏 = [ + Zβ ) × sx ̅̅̅̅̅ 𝑇𝑀 √𝒏 = 𝟔. 𝟓𝟖𝟎 rearrange the equation to solve for n ] √𝒏 = [ (1.04 + 1.04 ) × $806.81 ] $255.05 𝒏 = 𝟒𝟑. 𝟐 Evaluation of Sample Results using a Hypothesis Test During the planning phase, the standard deviation of the recorded values would be the only value available to calculate the required sample size. If the sample results indicate the standard deviation might actually be greater, we should consider using the standard deviation of the sample results. 1.04 x 209.56 $ 217.95 + 2,295.47 $ 2,513.42 Zβ number of std dev Sx/√n std error of the means allowance for sampling risk μ hypothetical mean Critical value 0.15 risk of incorrect acceptance 1,390.09 Sx std deviation of sample 44 sample size $ 2,425.57 sample mean The hypothetical mean is the book value less tolerable misstatement. We need evidence indicating there is a low probability the true value is less than the hypothetical mean. The critical value is calculated by adding an allowance for sampling risk to the hypothetical mean. In this example the $2,425 sample mean is less than the critical value indicating there is unacceptable risk that accounts receivable might be is overstated. This indicates that we need to obtain more evidence before we can conclude on the account. If our sample mean exceeded the critical value we could conclude that the account is not materially overstated. There is less than a 15% probability of selecting a sample with a $2,513 mean from population with a $2,134,785 balance. 14 Evaluation by Comparing the Projected Sample Results to Tolerable Misstatement $ 2,550.52 ̅̅̅̅ 𝐵𝑉 ave. book value - 2,425.57 sample average $ 124.95 average misstatement 0.15 1.04 x 209.56 $ 217.95 $ 2,371,983.60 - 2,255,775.24 $ 116,208.36 237,198.36 risk of incorrect acceptance $ 120,990.00 Zβ number of std dev Sx/√n std error of the means allowance for sampling risk 202,693.50 book value projected value projected misstatement TM tolerable misstatement allowance for sample risk desired allowance for sample risk Alternatively, we reach the same conclusion by projecting the estimated misstatement from our sample results to population. Although the $116,208 projected misstatement is less than tolerable misstatement, accounting standards require us to add an allowance for sampling risk. The difference between the projected misstatement and tolerable misstatement results in a $120,990 allowance for sampling risk. A $202,693 allowance for sampling risk would be necessary to achieve 15% Beta risk. 15 Appendix C rubric for the simulation workpapers 1 Workpapers are turned in on time 2 Each workpaper includes the appropriate common information: client name, transaction cycle, account, nature of test, objective, s assertions and tolerable error s sign-off and date should be updated for each work paper 3 Workpaper 3 s s s a dollar amount from a confirmation response or the results of the alternative procedures, for each item in the sample a tick mark for each discrepancy sum, mean and standard deviation calculated from sample results 4 Workpaper 2 s s s the required sample size calculation reflect this year’s population and risk parameters Zβ = 0.84, Zα/2 = 1.28, population size = 1,000, tolerable error $290,814.44, and standard deviation = $1,204.33 critical value is calculated from sample results in workpaper 3 the conclusion is appropriate for the critical value 5 Workpaper 1 s sample size and dates in the procedure description are appropriate s the conclusion is consistent with workpaper 2 16 References AICPA Audit Sampling Guide Task Force. 2008 AICPA. Audit Guide: Audit Sampling, 2.30. New York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. Auditing Standards Board. 2011. Statements on Auditing Standards 122-124, York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. New Author 2009. Monhemius, J., and Durkin, K. 2009. Detecting Circular Cash Flow. Journal of Accountancy Vol. 208(6): 23-30. Retrieved from http://www.journalofaccountancy.com/Issues/2009/Dec/20091793 Securities and Exchange Commission, 1940. Accounting Standards Release No. 19. Dec, 5. In the Matter of McKesson & Robbins, Section 1, Summary of Findings and Conclusions. Retrieved from http://sechistorical.org/museum/papers/1940/ 17