Document

advertisement

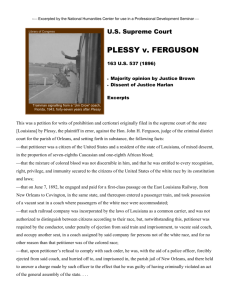

P6 | APUSH | Ms. Wiley | Jim Crow America, D___ Name: Directions: Analyze each source and respond to all prompts/questions. Consider the following overarching questions as you work through the sources: How do the events of the last quarter of the 19th century demonstrate the failure of Reconstruction efforts? (Revisit Sources on Reconstruction document from Period 5.) What was hiding under the illusion of 'separate but equal'? What did the phrase really equate to? How did the Court's ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) demonstrate racial attitudes of the time? A. Source: ‘Jim Crow’ America Jim Crow was the name of the racial caste system which operated primarily, but not exclusively, in Southern and border states, between 1877 and the mid-1960s. Jim Crow was more than a series of rigid anti-black laws. It was a way of life. Under Jim Crow, African Americans were relegated to the status of second class citizens. Jim Crow represented the legitimization of anti-black racism. Many Christian ministers and theologians taught that whites were the Chosen people, blacks were cursed to be servants, and God supported racial segregation. Craniologists, eugenicists, phrenologists, and Social Darwinists, at every educational level, reinforced the belief that blacks were biologically, intellectually, and culturally inferior to whites. Pro-segregation politicians gave eloquent speeches on the great danger of integration: the “mongrelization” of the white race. Newspaper and magazine writers routinely referred to blacks as n-----s, coons, and darkies. Even children's games portrayed blacks as inferior beings. The following Jim Crow etiquette norms show how inclusive and pervasive these norms were. These acts were known as Jim Crow laws, named after a popular minstrel show character (see page 6 for more on minstrel shows). Restaurants/ It shall be unlawful to conduct a restaurant or other place for the serving of food in the city, at which white and colored people are served in the same room. Alabama Pool and Billiard Rooms/ It shall be unlawful for a negro and white person to play together or in company with each other at any game of pool or billiards. Alabama Toilet Facilities/ Every employer of white or negro males shall provide for such white or negro males reasonably accessible and separate toilet facilities. Alabama Cohabitation/ Any negro man and white woman, or any white man and negro woman, who are not married to each other, who shall habitually live in and occupy in the nighttime the same room shall each be punished by imprisonment not exceeding twelve (12) months, or by fine not exceeding five hundred ($500.00) dollars. Florida Education/ The schools for white children and the schools for negro children shall be conducted separately. Florida, Mississippi Intermarriage/ It shall be unlawful for a white person to marry anyone except a white person. Any marriage in violation of this section shall be void. Georgia Barbers/ No colored barber shall serve as a barber [to] white women or girls. Georgia Amateur Baseball/ It shall be unlawful for any amateur white baseball team to play baseball on any vacant lot or baseball diamond within two blocks of a playground devoted to the Negro race, and it shall be unlawful for any amateur colored baseball team to play baseball in any vacant lot or baseball diamond within two blocks of any playground devoted to the white race. Georgia Wine and Beer/ All persons licensed to conduct the business of selling beer or wine...shall serve either white people exclusively or colored people exclusively and shall not sell to the two races within the same room at any time. Georgia 1. How do you suspect Jim Crow laws impacted the African American psyche? … The white American psyche? 2. Which Jim Crow law was most shocking/interesting to you? Why? 3. What does the term “Jim Crow” mean? 1 B. Source: Louisiana Literacy Test (read context and then complete at least 1 page of the test on attachment) Prior to passage of the federal Voting Rights Act in 1965, Southern states maintained elaborate voter registration procedures deliberately designed to deny the vote to nonwhites. The test results were rigged by biased registrars who were the sole judges whether — in their opinion — you were sufficiently "literate" to "pass." They often did not require white applicants to take the test at all, or always "passed" those who did. Black applicants were almost always required to take the test, even those with college degrees, and they were almost always deemed to have "failed." There were many other interlocking systems used to deny African Americans (and in some regions, Latinos and Native Americans) the right to vote so as to ensure that political power remained exclusively white-only. In addition to tests and registration procedures, these systems of racial discrimination and oppression included poll taxes, police power and intimidation, economic retaliation, and violent white-terrorism. Poll taxes: A "poll tax" was a tax you had to pay in order to vote. At one time, state and local poll taxes were common, but by the mid-20th century they were mainly limited to the South as a means of preventing blacks and poor whites from voting (and lending support to the dreaded Republican). For impoverished families, it was a sum that forced them to choose between voting and necessities of life. And many of those at the very bottom of the economic ladder — sharecroppers, tenant farmers, agricultural laborers, coal miners, timber workers, and so on — existed entirely outside the cash economy. They had to buy their necessities at over-priced plantation or company stores on credit and their pay went directly to the store, not them. Thus, voting was out of the question. Police intimidation: The various state, county, and local police forces — all white of course — routinely intimidated and harassed blacks who tried to register. They arrested would-be voters on false charges and beat others for imagined transgressions; and often this kind of retribution was directed not only at the man or woman who dared try to register, but against family members as well, even the children. Economic retaliation: Throughout the deep South, white businesses, employers, banks, and landlords were organized into White Citizens Councils who inflicted economic retaliation against nonwhites who tried to vote. Evictions. Firings. Boycotts. Foreclosures. Small-scale farmers needed a crop loan each year in order to buy seed, fertilizer, fuel, and food until they could sell their cotton or tobacco after picking. Banks denied those loans to blacks who tried to vote, forcing them off the land. White terrorism: And if economic pressure proved insufficient, the Ku Klux Klan was ready with violence and mayhem. Cross-burnings. Night riders. Beatings. Rapes. Church bombings. Arson of businesses and homes. Murder and mob lynching’s, drive-by shootings and sniper assassinations. Today these people would be called "terrorists," but back then the white establishment saw them as defenders of the "southern way of life" and upholders of "our glorious southern heritage." While in theory there were standard state-wide registration procedures, in real-life the individual county Registrars and clerks did things their own way. The exact procedure varied from county to county, and within a county it varied from day to day according to the mood of the Registrar. And, of course, it almost always varied according to the race of the applicant. Note: Literacy tests and poll taxes were not abolished until 1965, when the Voting Rights Act was passed, under the Lyndon B. Johnson administration. 4. What are your thoughts regarding this test and the way in which it was typically administered? (respond after reading context and completing at least 1 page of the test) 5. How does this test, and the other mechanisms described above, violate the 14th and/or 15th Amendments? Be specific. Revisit Civil War Amendments document from Period 5. 2 C. Source: Summary of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) The June 7, 1892 arrest of Homer Plessy (see right) was part of a strategy orchestrated by a small civic group of black professionals seeking to overturn the 1890 Louisiana Separate Car Act. Plessy, who was by blood only one-eighth African and who easily "passed" as white, boarded a whites-only compartment on the East Louisiana Railway and, as planned, was arrested shortly thereafter by a private detective. Railroad officials viewed the law -- which mandated that they provide separate accommodations for blacks and whites -- as an expensive and inconvenient burden and cooperated with the citizens' group in arranging to have Plessy safely arrested before leaving the city limits of New Orleans. The civic group planned to utilize Plessy's light skin color in demonstrating the arbitrariness -- and unconstitutionality -- of the segregation law once his case was prosecuted. Specifically, Plessy's attorney argued that Louisiana's segregation law violated both the Thirteenth Amendment (barring slavery) and the Fourteenth Amendment (guaranteeing all people "equal protection" under the law). Through several appeals, however, the Louisiana courts upheld both Plessy's conviction and the constitutionality of the segregation law, and in 1896 the case reached the Supreme Court. Writing for a 7-1 majority, Justice Henry Brown accepted Plessy's contention that the "object of the [Fourteenth] amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the law." However, Brown drew a distinction between political equality and social equality: "Legislation is powerless to eradicate racial instincts or to abolish distinctions based on physical differences, and the attempt to do so can only result in accentuating the differences of the present situation. If the civil and political rights of both races be equal, one cannot be inferior to the other civilly or politically. If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them on the same plane." Finally, Brown rejected Plessy's claim that assignment to the blacks-only car conferred "a badge of inferiority," stating that this was true only if "the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it." Justice John Marshall Harlan, a former slave owner and staunchly pro-slavery antebellum politician, issued the Court's sole dissent. In a scathing opinion, Harlan refuted Brown's assertion that the Louisiana law discriminated equally against both blacks and whites. "Everyone knows," he wrote, "that the statute in question had its origin in the purpose, not so much to exclude white persons from railroad cars occupied by blacks, as to exclude colored people from coaches occupied by or assigned to white persons." Harlan sharply disagreed with the majority's assessment that segregation on the railcars did not violate blacks' constitutionally protected right to equal protection of the law. However, although he argued eloquently for a "color-blind" reading of the Constitution, Harlan, like Brown, did not advocate social equality among the races. Rather, his point of departure from the majority opinion was his belief that legally imposed segregation denied political equality. In a key passage of his dissent, Harlan stated: "The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth, and in power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time, if it remains true to its great heritage, and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty. But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law." Although nowhere in the opinion can the phrase "separate but equal" be found, the Court's ruling in Plessy effectively established the rule that "separate" facilities for blacks and whites were constitutional as long as they were "equal" -- a principle that Southern states quickly extended to many other forms of public accommodation, such as public schools, restaurants, theaters, restrooms, and even drinking fountains. Widely regarded today as one of the Court's worst and most damaging opinions, Plessy stood as legal precedent until the 1954 landmark case Brown v. Board of Education, which began the process of ending more than 50 years of legally sanctioned segregation. Although it did not explicitly adopt Harlan's "colorblind" standard in Brown, a unanimous Court rejected the logic of the Plessy majority. Writing for the Court in Brown, Chief Justice Earl Warren stated: "We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." 6. Construct a list of the most important facts from the Plessy summary: 7. Is ‘separate but equal’ in line with the 14th Amendment? Be specific. 3 D. Source: The Court’s Decision: Justice Brown’s Majority Opinion in Plessy (1896) … The object of the [14th] amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the law, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either. Laws permitting, and even requiring, their separation in places where they are liable to be brought into contact do not necessarily imply the inferiority of either race to the other, and have been generally, if not universally, recognized as within the competency of the state legislatures in the exercise of their police power. The most common instance of this is connected with the establishment of separate schools for white and colored children, which has been held to be a valid exercise of the legislative power even by courts of States where the political rights of the colored race have been longest and most earnestly enforced. … Gauged by this standard, we cannot say that a law which authorizes or even requires the separation of the two races in public conveyances is unreasonable, or more obnoxious to the Fourteenth Amendment than the acts of Congress requiring separate schools for colored children in the District of Columbia, the constitutionality of which does not seem to have been questioned, or the corresponding acts of state legislatures. We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff's argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it. The argument necessarily assumes that if, as has been more than once the case, and is not unlikely to be so again, the colored race should become the dominant power in the state legislature, and should enact a law in precisely similar terms, it would thereby relegate the white race to an inferior position. We imagine that the white race, at least, would not acquiesce in this assumption. The argument also assumes that social prejudices may be overcome by legislation, and that equal rights cannot be secured to the negro except by an enforced commingling of the two races. We cannot accept this proposition. If the two races are to meet upon terms of social equality, it must be the result of natural affinities, a mutual appreciation of each other's merits and a voluntary consent of individuals. When the government, therefore, has secured to each of its citizens equal rights before the law and equal opportunities for improvement and progress, it has accomplished the end for which it was organized and performed all of the functions respecting social advantages with which it is endowed." Legislation is powerless to eradicate racial instincts or to abolish distinctions based upon physical differences, and the attempt to do so can only result in accentuating the difficulties of the present situation. If the civil and political rights of both races be equal one cannot be inferior to the other civilly or politically. If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane. It is true that the question of the proportion of colored blood necessary to constitute a colored person, as distinguished from a white person, is one upon which there is a difference of opinion in the different States, some holding that any visible admixture of black blood stamps the person as belonging to the colored race, others that it depends upon the preponderance of blood, and still others that the predominance of white blood must only be in the proportion of three fourths. But these are question to be determined under the laws of each State and are not properly put in issue in this case. Under the allegations of his petition it may undoubtedly become a question of importance whether, under the laws of Louisiana, the petitioner belongs to the white or colored race. 8. Summarize the majority opinion in your own words: 9. Is the majority opinion correct in its constitutional assertions? Why or why not? 4 E. Source: Justice Harlan’s Dissent in Plessy (1896) … I deny that any legislative body or judicial tribunal may have regard to the race of citizens when the civil rights of those citizens are involved. Indeed, such legislation, as that here in question, is inconsistent not only with that equality of rights which pertains to citizenship, National and State, but with the personal liberty enjoyed by every one within the United States.... It was said in argument that the statute of Louisiana does not discriminate against either race, but prescribes a rule applicable alike to white and colored citizens. But this argument does not meet the difficulty. Every one knows that the statute in question had its origin in the purpose, not so much to exclude white persons from railroad cars occupied by blacks, as to exclude colored people from coaches occupied by or assigned to white persons. Railroad corporations of Louisiana did not make discrimination among whites in the matter of accommodation for travelers. The thing to accomplish was, under the guise of giving equal accommodation for whites and blacks, to compel the latter to keep to themselves while travelling in railroad passenger coaches. No one would be so wanting in candor as to assert the contrary.... … If a State can prescribe, as a rule of civil conduct, that whites and blacks shall not travel as passengers in the same railroad coach, why may it not so regulate the use of the streets of its cities and towns as to compel white citizens to keep on one side of a street and black citizens to keep on the other? Why may it not, upon like grounds, punish whites and blacks who ride together in street cars or in open vehicles on a public road of street? Why may it not require sheriffs to assign whites to one side of a court-room and blacks to the other? And why may it not also prohibit the commingling of the two races in the galleries of legislative halls or in public assemblages convened for the considerations of the political questions of the day? Further, if this statute of Louisiana is consistent with the personal liberty of citizens, why may not the State require the separation in railroad coaches of native and naturalized citizens of the United States, or of Protestants and Roman Catholics? … The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth and in power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time, if it remains true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty. But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved. It is, therefore, to be regretted that this high tribunal, the final expositor of the fundamental law of the land, has reached the conclusion that it is competent for a State to regulate the enjoyment by citizens of their civil rights solely upon the basis of race. In my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott case.... The present decision, it may well be apprehended, will not only stimulate aggressions, more or less brutal and irritating, upon the admitted rights of colored citizens, but will encourage the belief that it is possible, by means of state enactments, to defeat the beneficent purposes which the people of the United States had in view when they adopted the recent amendments of the Constitution, by one of which the blacks of this country were made citizens of the United States and of the States in which they respectively reside, and whose privileges and immunities, as citizens, the States are forbidden to abridge. Sixty millions of whites are in no danger from the presence here of eight millions of blacks. The destinies of the two races, in this country, are indissolubly linked together, and the interests of both require that the common government of all shall not permit the seeds of race hate to be planted under the sanction of law. What can more certainly arouse race hate, what more certainly create and perpetuate a feeling of distrust between these races, than state enactments, which, in fact, proceed on the ground that colored citizens are so inferior and degraded that they cannot be allowed to sit in public coaches occupied by white citizens? That, as all will admit, is the real meaning of such legislation as was enacted in Louisiana.... 10. Summarize Justice Harlan’s dissent in your own words: 11. Is the dissent correct in its constitutional assertions? Why or why not? 5 F. Source: Ida B. Wells on Lynching A daughter of slaves, Ida B. Wells was born in Mississippi in 1862, during the Civil War. A journalist, Wells led an anti-lynching crusade in the United States throughout the Gilded Age, and went on to found and become integral in groups striving for African-American justice. Our country's national crime is lynching. It is not the creature of an hour, the sudden outburst of uncontrolled fury, or the unspeakable brutality of an insane mob. It represents the cool, calculating deliberation of intelligent people who openly avow that there is an "unwritten law" that justifies them in putting human beings to death without complaint under oath, without trial by jury, without opportunity to make defense, and without right of appeal. The alleged menace of universal suffrage having been avoided by the absolute suppression of the negro vote, the spirit of mob murder should have been satisfied and the butchery of negroes should have ceased. But men, women, and children were the victims of murder by individuals and murder by mobs, just as they had been when killed at the demands of the "unwritten law" to prevent "negro domination." Negroes were killed for disputing over terms of contracts with their employers. If a few barns were burned some colored man was killed to stop it. If a colored man resented the imposition of a white man and the two came to blows, the colored man had to die, either at the hands of the white man then and there or later at the hands of a mob that speedily gathered. In fact, for all kinds of offenses--and, for no offenses--from murders to misdemeanors, men and women are put to death without judge or jury; so that, although the political excuse was no longer necessary, the wholesale murder of human beings went on just the same. A new name was given to the killings and a new excuse was invented for so doing. Again the aid of the "unwritten law" is invoked, and again it comes to the rescue. During the last ten years a new statute has been added to the "unwritten law." This statute proclaims that for certain crimes or alleged crimes no negro shall be allowed a trial; that no white woman shall be compelled to charge an assault under oath or to submit any such charge to the investigation of a court of law. The result is that many men have been put to death whose innocence was afterward established; and to-day, under this reign of the "unwritten law," no colored man, no matter what his reputation, is safe from lynching if a white woman, no matter what her standing or motive, cares to charge him with insult or assault. 12. What crimes against blacks are discussed in this passage? G. Source: Minstrel Show, Cotton and Chick Watts Blackface https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-_swtbIi2F0 Though minstrelsy can be traced back to the 1600s in Europe and 1830s America, it did not become hugely popular until the post-Civil War era. Minstrel shows were a “sensation” among whites. Due to the fact that blacks often weren’t allowed to take part in performances due to segregation, white performers would rub burnt cork, or greasepaint, on their faces to give themselves the pigmentation of a black person. They would dress in costumes while performing songs to audiences that mocked and negatively represented the culture of African Americans. When possible, blacks were hired to play the black characters themselves, though their physical appearance was caricaturized. Minstrel shows were considered mainstream entertainment for many and did not fall out of favor in some regions of the country until the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. 13. How is the African American character portrayed throughout the clip? 14. How do you suspect minstrelsy shaped white Americans’ views of blacks? 15. Why do you suspect shows like the one seen here were appealing to mass audiences? 16. Some historians claim that comedians such as Chris Rock have “simply reverted back to minstrelsy stereotypes in their acts.” To what extent has minstrelsy affected contemporary black comedy? 6