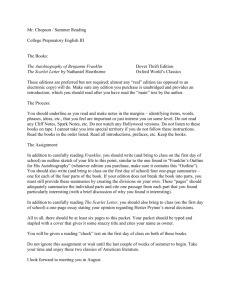

Introduction to American Literature

advertisement