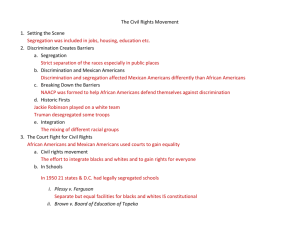

TAKS Remediation Lesson #1

advertisement

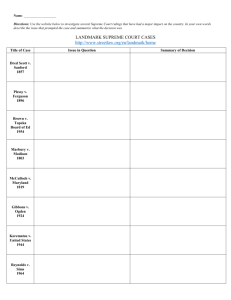

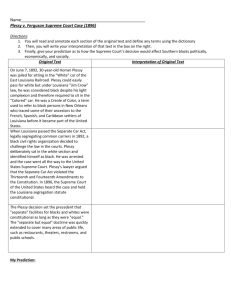

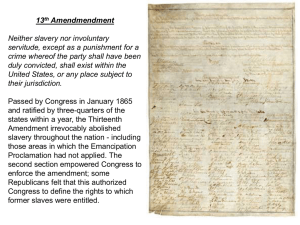

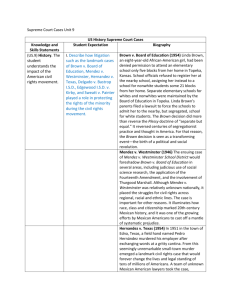

Supporting standards comprise 35% of the U. S. History Test 9 (I) Supporting Standard (9) The student understands the impact of the American civil rights movement. The Student is expected to: (I) Describe how litigation such as the landmark cases of Brown v. Board of Education, Mendez v. Westminster, Hernandez v. Texas, Delgado v. Bastrop I. S. D., Edgewood I. S. D. v. Kirby, & Sweatt v. Painter played a role in protecting the rights of the minority during the civil rights movement Supporting Standard (9) The student understands the impact of the American civil rights movement. The Student is expected to: (I) 1 Describe how litigation such as the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education played a role in protecting the rights of the minority during the civil rights movement Marker placed at Press and Royal Streets in New Orleans on February 12, 2009 commemorating the arrest of Homer Plessy on June 7, 1892 for violating the Louisiana 1890 Separate Car Act. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments •S Thirteenth Amendment—Congressional passage January 1865; ratification December 1865 Prohibited slavery in the U.S. •C Fourteenth Amendment—Congressional passage June 1866; ratification July 1868 gave right of citizenship to freedmen •V Fifteenth Amendment—Congressional passage February 1869; ratification March 1870 prohibited denial of franchise or the vote because of race, color, or past servitude Segregation in American Education—Plessy v. Ferguson • • • • • • John H. Ferguson (1806-1887), the Orleans Parish criminal court judge who ruled in the original case John Marshall Harlan, the only Supreme Court Justice who ruled in favor of Homer A. Plessy The Supreme Court (7-1) upholds a Louisiana law requiring separate railroad cars for Blacks and whites The ruling gave impetus to a host of Jim Crow laws that began to be introduced in the South The Background Plessy v. Ferguson Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), is a landmark U. S. Supreme Court ruling upholding the constitutionality of state laws requiring racial segregation in public facilities under the doctrine of “separate but equal.” The decision was handed down by a vote of 7 to 1 with the majority opinion written by Justice Henry Billings Brown and the dissent written written by by Justice Justice John John Marshall Marshall Harlan. Harlan. “Separate but equal” remained standard doctrine in U.S. law until its repudiation in the 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education. After the Supreme Court ruling, the New Orleans Comité des Citoyens (Committee of Citizens, a committee dedicated to repeal Louisiana’s Separate Car Act of 1890), which had which had brought brought the the suit suit and and had had arranged for Homer Plessy’s arrest on on June June 7, 7, 1892, in an act of civil disobedience in order to challenge Louisiana’s segregation law, replied, “We, as freemen, still believe that we were right and our cause is law, sacred.” Plessy was Plessy was born born aa free free man man and was an “octoroon” (someone of seven-eighths Caucasian descent and one-eighth African descent). However, under Louisiana law, he was classified as black, and thus required to sit in the “colored” car. On June 7, 1892, Plessy bought a first class ticket at the Press Street Depot and boarded a “whites only” car. After Plessy Plessy took took aa seat seat in in the the whites-only railway car, he was asked to vacate it, and sit instead in the blacks-only car. Plessy refused and was arrested immediately by the detective. As planned, the train was stopped, and Plessy was taken off the train at Press and Royal streets. Plessy was remanded for trial in Orleans Parish. The The defense built its case on violations of Plessy’s rights under under the the Thirteenth Amendment, prohibiting slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees the same rights to all citizens of the United States, and the equal protection of those rights, against the deprivation of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Justice John Marshall Harlan, who decried the excesses of the Ku Klux Klan, wrote a scathing dissent in which he predicted the court’s decision would become as infamous as that of Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857). As heralded as this dissent may be, in which Harlan called for a “color-blind” constitution, it should be noted that he did not view all races as equal. The case helped cement the legal foundation for the doctrine of separate but equal, the idea that segregation based on classifications was legal as long as facilities were of equal quality. However, Southern state governments refused to provide blacks with genuinely equal facilities and resources in the years after the Plessy decision. The states not only separated races but, in actuality, ensured differences in quality. In January 1897, Homer Plessy pleaded guilty to the violation and paid the fine. Brown v. Board of Education Brown v. Board of Education was a landmark U. S. Supreme Court ruling in which the Court declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional. The decision overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which allowed statesponsored segregation, insofar as it applied to public education. Handed down on May 17, 1954, the Warren Court’s unanimous (9–0) decision decision stated stated that that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” As As aa result, result, de jure racial segregation was ruled a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This ruling paved the way for integration and was a major victory of the civil rights movement. The plaintiffs in Brown asserted that this system of racial separation, while masquerading as providing separate but equal treatment of both white and black Americans, instead perpetuated inferior accommodations, services, and treatment for black Americans. Racial segregation in education varied widely from the 17 states that required racial segregation to the 16 that prohibited it. The named plaintiff, Oliver L. Brown, was a parent, a welder in the shops of the Santa Fe Railroad, an assistant pastor at his local church, and an African American. He was convinced to join the lawsuit by Scott, a childhood friend. Brown’s daughter Linda, a third grader, had to walk six blocks to her school bus stop to ride to Monroe Elementary, her segregated black school one mile away, while Sumner Elementary, a white school, was seven blocks from her house. As directed by the NAACP leadership, the parents each attempted to enroll their children in the closest neighborhood school in the fall of 1951. They were each refused enrollment and directed to the segregated schools. The District Court ruled in favor of the Board of Education, citing the U.S. Supreme Court precedent set in Plessy v. Ferguson. The case of Brown v. Board of Education as heard before the Supreme Court combined five cases. All were NAACP-sponsored cases. The Kansas case was unique among the group in that there was no contention of gross inferiority of the segregated schools’ physical plant, curriculum, or staff. The district court found substantial equality as to all such factors. The The NAACP’s chief counsel, Thurgood Marshall—who was later appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967—argued the case before the Supreme Court for the plaintiffs. Assistant attorney general Paul Wilson—later distinguished emeritus professor of law at the University of Kansas—conducted the state’s ambivalent defense in his first appellate trial. On May 17, 1954, these men, members of the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional. Warren convened a meeting of the justices, and presented to them the simple argument that the only reason to sustain segregation was an honest belief in the inferiority of Negroes. Warren further submitted that the Court must overrule Plessy to maintain its legitimacy as an institution of liberty, and it must do so unanimously to avoid massive Southern resistance. He began to build a unanimous opinion. The key holding of the Court was that, even if segregated black and white schools were of equal quality in facilities and teachers, segregation by itself was harmful to black students and unconstitutional. They found that a significant psychological and social disadvantage was given to black children from the nature of segregation itself, drawing on research conducted by Kenneth Clark assisted by June Shagaloff. This aspect was vital because the question was not whether the schools were “equal,” which which under under Plessy they nominally should have been, but whether the doctrine of separate was constitutional. constitutional. The justices answered with a strong “no.” “Segregation with with the the sanction sanction of of law, law, therefore, therefore, has has aa tendency tendency to to [retard] [retard] the educational and mental development of negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racial[ly] integrated school system. . . . We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate Separate educational educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws the laws guaranteed guaranteed by by the the Fourteenth Fourteenth Amendment.” Amendment.” In 1955, the Supreme Court considered arguments by the schools requesting relief concerning the task of desegregation. In their decision, decision, which which became became known known as as “Brown II” the the court court delegated delegated the task of carrying out school desegregation to district courts with with orders that desegregation occur “with all deliberate speed.” Supporters of the earlier decision were displeased with this decision. The language “all deliberate speed” was seen by critics as too ambiguous to ensure reasonable haste for compliance with the court's instruction. Many Southern states and school districts interpreted “Brown II” as legal justification for resisting, delaying, and avoiding significant integration for years—and in some cases for a decade or more—using such tactics as closing down school systems, using state money to finance segregated “private” schools, and “token” integration where a few carefully selected black children were admitted to former white-only schools but the vast majority remained in underfunded, unequal black schools. Supporting Standard (9) The student understands the impact of the American civil rights movement. The Student is expected to: (I) 2 Describe how litigation such as the landmark case of Mendez v. Westminster played a role in protecting the rights of the minority during the civil rights movement Mendez v. Westminster Mendez, et al v. Westminster School District of Orange County, et al, was a 1946 federal court case that challenged racial segregation in Orange County, California schools. In its ruling, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that the segregation of Mexican & Mexican American students into separate “Mexican schools” was unconstitutional. Five Mexican-American fathers, (Thomas Estrada, William Guzman, Gonzalo Mendez, Frank Palomino, and Lorenzo Ramirez) challenged the practice of school segregation in the U. S. District Court in Los Angeles. They claimed that their children, along with 5,000 other children of “Mexican” ancestry, were victims victims of of unconstitutional unconstitutional discrimination by being forced to attend separate “schools for Mexicans” in in the the Westminster, Westminster, Garden Garden Grove, Grove, Santa Santa Ana, Ana, & & El El Modena school districts of Orange County. The plaintiffs were represented by an established Jewish American civil rights attorney, David Marcus. Jackson County Funding for the lawsuit was primarily paid for initially by the Courthouse, of the lead plaintiff Gonzalo Mendez who site began the lawsuit when his three children were denied entrance to their local Westminster school. Both the lower court &Westminster the Ninth Federal District Court Mendez v. of Appeals in San Francisco, ruled that the segregation practices violated the Fourteenth Amendment. Trial Supporting Standard (9) The student understands the impact of the American civil rights movement. The Student is expected to: (I) 4 Describe how litigation such as the landmark case of Hernandez v. Texas played a role in protecting the rights of the minority during the civil rights movement Hernandez v. Texas Hernandez v. Texas (1954) was a landmark U. S. Supreme Court case that ruled that Mexican Americans and all other racial groups in the U. S. had equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. Pedro Hernandez, a Mexican agricultural worker, was convicted for the murder of Joe Espinosa. Hernandez’s legal team set out to demonstrate that the jury could not be impartial unless members of non-Caucasian races were allowed on the juryselecting committees; no Mexican American had been on a jury for more than 25 years in Jackson County, Tx., the county in which the case was tried. Chief Justice Earl Warren & the Court unanimously ruled in favor of Hernandez, requiring that he be retried with a jury composed without regard to ethnicity. The Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment protects Americans regardless of racial heritage. Hernández v. Texas was the brown Brown v. Board of Education. It was the first time that MexicanAmerican lawyers appeared before the United States Supreme Court, and their victory established a landmark in Mexican-American civil rights. Supporting Standard (9) The student understands the impact of the American civil rights movement. The Student is expected to: (I) 4 Describe how litigation such as the landmark case of Delgado v. Bastrop I. S. D. played a role in protecting the rights of the minority during the civil rights movement Until the late 1940s the public education system in Texas for Mexican Americans offered segregated campuses with often minimal facilities and a curriculum frequently limited to vocational training. The 1950 United States census showed that the median educational attainment for persons over twenty-five was 3.5 years for those with Spanish surnames and, by comparison, 10.3 years for other white Americans; about 27 percent of persons over twenty-five with Spanish surnames had received no schooling at all. No substantive legal suit had been initiated since Del Rio ISD vs. Salvatierraqv (1930), in which Mexican Americans claimed they had been denied use of facilities used by “other white races” in the same school. In 1948 1948 the the League League of United Latin American Citizens, joined by the American G. I. Forum of Texas, successfully challenged these inequities of the Texas public school system in Delgado vs. Bastrop ISD. In 1947 the Ninth Circuit Court in California found that separation “within one of the great races” without a specific state law requiring the separation was not permitted; therefore, segregation of MexicanAmerican children, who were considered Caucasian, was illegal. In Texas, following this ruling, the attorney general, in response to an inquiry by Gustavo C. (Gus) Garciaqv, a Mexican-American attorney, agreed that segregation of Mexican-American children in the public school system by national origin was unlawful and pedagogically justified only by scientific language tests applied to all students. On June 15, 1948, LULAC (with Garcia as attorney) filed suit against the Bastrop Independent School District and three other districts. Representing Minerva Delgado and twenty other Mexican-American parents, the suit charged segregation of Mexican children from other white races without specific state law and in violation of the attorney general’s opinion. In addition the suit accused these districts of depriving such children of equal facilities, services, and education instruction. Judge Ben H. Rice of the United States District Court, Western District of Texas, agreed and ordered the cessation of this separation by September 1949. However, the court did allow separate classes on the same campus, in the first grade only, for language-deficient or non-English-speaking students as identified by scientific and standardized tests applied to all. The Delgado decision undermined the rigid segregation of Mexican Americans and began a ten-year struggle led by the American G.I. Forum and LULAC, which culminated in 1957 with the decision in Herminca Hernandez et al. v. Driscoll Consolidated ISD, which ended pedagogical and de jure segregation in the Texas public school system. Supporting Standard (9) The student understands the impact of the American civil rights movement. The Student is expected to: (I) 5 Describe how litigation such as the landmark case of Edgewood I. S. D. v. Kirby played a role in protecting the rights of the minority during the civil rights movement EDGEWOOD ISD V. KIRBY In Edgewood Independent School District et al. v. Kirby et al. (1989), a landmark case concerning public school finance, the Mexican American Legal Defense & Educational Fund filed suit against commissioner of education William Kirby on May 23, 1984, in Travis County on behalf of the Edgewood Independent School District, San Antonio, citing discrimination against students in poor school districts. The plaintiffs The plaintiffs charged charged that that the the state’s methods of funding public schools violated at least four principles of the state constitution, which obligated the state legislature to provide an efficient and free public school system. Initially, eight school districts and twenty-one parents were represented in the Edgewood case. Ultimately, however, sixty-seven other school districts as well as many other parents and students joined the original plaintiffs. The Edgewood lawsuit occurred after almost a decade of legal inertia on public school finance following the Rodríguez v. San Antonio ISD case of 1971, which asked the courts to address unfairness in public school aid. The Rodríguez plaintiffs ultimately lost in the United States Supreme Court in 1973. The plaintiffs in the in the Edgewood Edgewood case case contested contested the the state’s reliance on local property taxes to finance its system of public education, contending that this method was intrinsically unequal because property values varied greatly from district to district, thus creating an imbalance in funds available to educate students on an equal basis throughout the state. In its opinion deciding the case (1989), the Texas Supreme Court noted that the Edgewood ISD, among the poorest districts in the state, had $38,854 in property wealth per student, while the Alamo Heights ISD, which is in the same county, had $570,109 per student. In addition, property-poor districts had to set a tax rate that averaged 74.5 cents per $100 valuation to generate $2,987 per student, while richer districts, with a tax rate of half that much, could produce $7,233 per student. These differences produced disparities in the districts’ abilities These to hire good teachers, build appropriate facilities, offer a sound curriculum, and purchase such important equipment as computers. In its original 1984 brief, MALDEF had declared that such gaps amounted to the denial of equal opportunity in and an “increasingly complex and technological society,” and asserted that this was contrary to the intent of the constitution’s Texas Education Clause. On April 29, 1987, State District Judge Harley Clark ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. the plaintiffs. He He found found that that the the state’s public school financing structure was unconstitutional and ordered the legislature to formulate a more equitable one by September 1989. The state appealed his decision to the Third Court of Appeals. On December 14, 1988, the appeals court justices reversed the lower court by a twoto-one decision on the grounds that education was not a basic right. It further proclaimed that the present system of public school financing was constitutional. The plaintiffs appealed the decision, however, taking it to the Texas Supreme Court on July 5, 1989. On October 2 the court delivered a unanimous 9–0 decision that sided with the Edgewood plaintiffs and ordered the state legislature to implement an equitable system by the 1990–91 school year. Following the court’s order, the legislature legislature met met in in four four consecutive consecutive and often contentious special sessions to resolve the financing issue. It ultimately called for a transfer of money from property-wealthy school districts to poor ones to equalize the amount each district spent to educate students. The press nicknamed this redistribution scheme, and scheme, and similar similar proposals proposals suggested suggested later, later, the the “Robin Hood” plan. On June 6, 1990, the legislature finally reached consensus and approved a funding bill that would increase state support to public schools by $528 million. Governor William Clements signed it into law the following day. The plaintiffs, however, were dissatisfied with the latest legislation and asked for another hearing in the Travis County District Court. The legislature ultimately satisfied the court-mandated new financing formulaby consolidating the 1,058 school districts into 188 County Education Districts to assure that public money spent per student would be equal. This would amount to $2,200 per student immediately and rise to $2,800 in four years, the result of setting a tax rate of 72 cents per $100 valuation, with an eventual increase to $1.00 per $100 valuation. Governor Ann Richards signed the bill into law on April 15, 1991. After continuous protest on the issue from property-wealthy districts the Supreme Court heard more arguments challenging the latest method of school finance and concluded in a 7–2 decision on January 22, 1992, that the plan was illegal. It held that the legislature had acted improperly in setting up the County Education Districts because they were unlawful taxing units under the Constitution of 1876. The court ordered the legislature to devise a new plan by June 1, 1993, but in the meantime it allowed school funding to continue through the CEDs. On May 28, 1993, the legislature passed a multi-option plan for reforming school finance. Under the plan, each school district would help to equalize funding through one of five methods: (1) merging its tax base with a poorer district, (2) sending money to the state to help pay for students in poorer districts, (3) contracting to educate students in other districts, (4) consolidating voluntarily with one or more other districts, or (5) transferring some of its commercial taxable property to another district’s tax rolls. If a district did not choose one of these options, the state would order the transfer of taxable property; if this measure failed to reduce the district's property wealth to $280,000 per student, the state would force a consolidation. This plan was signed into law by Governor Richards on May 31, 1993, and was accepted by Judge McCown. The action guaranteed that schools would receive funding for the 1993–94 academic year. Supporting Standard (9) The student understands the impact of the American civil rights movement. The Student is expected to: (I) 6 Describe how litigation such as the landmark case of Sweatt v. Painter played a role in protecting the rights of the minority during the civil rights movement Sweatt v. Painter Sweatt v. Painter (1950) was a U. S. Supreme Court case that that successfully case successfully challenged the “separate but equal” doctrine of racial segregation established established by by the 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson. The case was influential in the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education four years later. The case involved a black man, Heman Marion Sweatt, who was refused admission to University of Texas Law School, whose president was Theophilus Painter, on the grounds that the Texas State Constitution prohibited integrated education. At the time, no law school in Texas would admit black students, or, in the language of the time, “Negro” students. The state district court in Travis County, instead of granting the plaintiff a writ of mandamus, continued the case for six months. This allowed the state time to create a law school only for black students, which it established in Houston, rather than in Austin. The ‘separate’ law school and the college became the Thurgood Marshall School of Law at at Texas Texas Southern Southern University University (known then as “Texas State Law University for Negroes”). The trial court decision was affirmed by the Court of Civil Appeals and the Texas Supreme Court denied writ of error on further appeal. Sweatt and the NAACP next went to the federal courts, and the case ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court. W. J. Durham and Thurgood Marshall presented Sweatt’s case. The Supreme Court reversed the lower court decision, saying that the separate school failed to qualify, both because of quantitative differences in facilities and intangible factors, such as its isolation from most of the future lawyers with whom its graduates would interact. The court held that, when considering graduate education, intangibles must be considered as part of “substantive equality.” The documentation of the court’s decision itemized numerous differences identified. Fini