File

advertisement

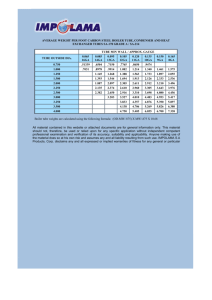

Lab Report #5: Chromatography and Applications Madison Stargell Section: BIOL 3520.507 TA: Dennis Carty Overall objective Chromatography can be used as a purifying technique by separating individual components in a mixture. In this lab, we use size exclusion chromatography with a sample of blood to separate hemoglobin and vitamin B12. While we can show that this is an effective technique in separating the components in blood, the overall objective is to show how chromatography is effective by using a Bradford assay and gel electrophoresis to indicate that these components are in fact separated. Background information In size exclusion chromatography, one is given a powerful method for determining and investigating molecular weight distribution in polymers. [1] It depends on the relative size or volume of a macromolecule with respect to the average pore size of the packing. Usually, silicabased packings are preferred because it insures the quality of your results and high efficiency in polymers while polystyrene gels are the most selected for organosoluble polymers. [3] These packings have tiny holes, are porous, and are packed together inside the column. During the process of chromatography when the buffer is added to move the proteins down the column, the protein binds to the oppositely charged beads as these beads act as temporary traps for the molecule of interest. Therefore, everything will pass through first before the protein we are interested in. [1] Also, larger molecules will move through first. The beads will trap smaller molecules, while the larger molecules pass through the column. In a mixture of vitamin B12 and hemoglobin, we can expect hemoglobin to pass through first because it is a larger molecule. The Bradford assay is based on the reaction of Coomassie G-250 with amino acids in proteins to measure the amount of protein in sample [4]. When we combine the dye and protein samples in a cuvette, there will be a color change in the dye from and reddish-brown to a brilliant blue. This color change occurs due the protein binding changes the dye from its cationic form to the anionic form at the 595 nm end of the spectrum [2]. Generally, the brighter the blue color, the higher the protein content in the substance. While one may be able to guess the absorbance value, we can see exact values when using a spectrophotometer. A standard curve will have to be used with the values of proteins in the cuvettes to help evaluate any unknown protein concentrations of the sample. Gel electrophoresis would be the next step after using Bradford assay. Gel electrophoresis has been used has a helpful tool in the birth of proteomics because of its ability to separate and determine relative size of different proteins. SDS electrophoresis was made popular in the 1970s by protein biochemists after a successful electrophoresis coupling denaturing IEF to SDS PAGE, which stands for sodium dodecyl polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. [5] After running the gel, one can measure protein bands and see how far they traveled along the gel from the negative to the positive end. The pore size of the gel decreased as the gel run from the negative to the positive end, so smaller sized molecules will travel farther. When a protein is too large to pass, it will stop, creating a line on the gel. It is important to create a standard or ladder to compare the other proteins to so you have find molecular mass after finding standard curve equation. The standard curve should have a negative linear trend because the farther the protein travels, the smaller the molecular mass. Results Table 1: Examination of collected fraction Tube #’s Color Tube 1 Tube 2 Tube 3 Tube 4 Tube 5 No color change No color change No color change No color change Strong blue Tube 6 Tube 7 Tube 8 Tube 9 Strong blue Light blue Light blue No color change Tube 10 No color change Table 2: Standard Curve Absorbance Values Sample Std. #1 Std. #2 Std. #3 Std. #4 Std. #5 Std. #6 Std. #7 Abs @595 nm 0.083 0.163 0.361 0.537 0.636 0.707 1.027 Concentration (mg/mL) 0.125 0.25 0.5 0.75 1 1.5 2 Table 3: Spectrophotometric data for collected fractions Figure 1: Standard curve: Tube #’s Tube 1 Abs @ 595 nm 0.332 Tube 2 Tube 3 0.018 0.022 Tube 4 Tube 5 0.501 0.749 Tube 6 Tube 7 Tube 8 Tube 9 Tube 10 0.923 0.382 0.273 0.095 0.227 Table 3: Final Concentration of Unknown Samples For the final concentrations, we can use the formula y=0.4711x+0.0898 to find each of the approximate concentrations for each sample. We had to calculate these values without the equation, so we drew a line of best fit and found approximate concentrations for the unknowns. After finding the concentration of each, we measured up with the pipettes to determine how many uL (microliters) were in each. To find the ug (micrograms), one can use the equation ug=concentration x microliters. Tube #’s Tube 1 Abs @ 595 nm 0.332 Concentration ≈0.4 uL in each tube 210 ug in each tube 84 Tube 2 Tube 3 0.018 0.022 ≈0.090 ≈0.095 75 45 6.75 4.275 Tube 4 Tube 5 Tube 6 0.501 0.749 0.923 ≈0.70 ≈1.53 ≈1.87 65 55 36 45.5 84.15 67.32 Tube 7 Tube 8 0.382 0.273 ≈0.52 ≈0.20 125 270 65 54 Tube 9 Tube 10 0.095 0.227 ≈0.130 ≈0.30 115 315 14.95 94.5 Table 4: Volume of Laemmli buffer added in each sample to make final concentration 0.5 µg/10 µl. For this portion, one can use the formula C1V1=C2V2 to find microliters of Laemmli buffer to add to each tube to give a dilution of 0.05 ug/uL for each tube. The values on the next page are the amounts added when using this equation for each tube. We had to manipulate a few of these values later and remove some of the volume from the original volumes because the volume of Laemmli buffer was too great to fit in a centrifuge tube. The appropriate values were calculated to what the micrograms and microliters would need to be. Tube #’s uL of Laemmli buffer added Tube 1 Tube 2 Tube 3 Tube 4 Tube 5 1680 140 80 920 1683 Tube 6 Tube 7 Tube 8 Tube 9 1346 1300 1080 300 Tube 10 1890 Conclusions These tubes were then allowed to rock and then pipetted into each of the wells on the gels. There were 5 uL of the samples added into each well per lane. Once the gels ran and were allowed to sit, there was no band formation. This could have occurred for a couple of different reasons. First of all, the samples could have been too diluted. Although we calculated them appropriately, the dilution factor may have been too low. If we increased the dilution factor, perhaps the bands may have formed. The lack of band formation also could have been attributed to there not being enough sample volume added in each lane. If we had increased the volume added, we may have had band formation occur. Both of these reasons could have contributed to the reason no bands formed. If we increased dilution factor and added more to the wells, we may have bands form. References 1. Boymirzaev, A.S., Turavev, A.S. (2010). Non-exclusion Effects in Aqueous Size-Exclusion Chromatography of Polysaccharides. Chinese Medicine 1, 28-29. 2. Carlsson, N., Kitts, C.C., Akerman, B. (2012). Spectroscopic characterization of Coomassie blue and its binding to amyloid fibrils. Anal Biochem 420, 33-40. 3. Howard, G.B., Barry, E.B., Jackson, C. (1994). Size Exclusion Chromatography. Anal Biochem 66, 595-620. 4. Ku, H.K., Lim, H.M., Oh, K.H., Yang, H.J., Jeong, J.S., and Kim, S.K. (2013). Interpretation of protein quantificatin using the Bradford assay: comparison with two calculation models. Anal Biochem 434, 178-180. 5. Rabilloud, T., Chevallet, M., Luche, S., Lelong, C. (2010). Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis in proteomics: Past, present, and future. Journal of Proteomics 73, 20642077.