Slaughterhouse Five

advertisement

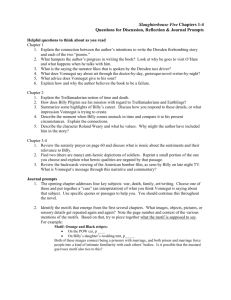

SLAUGHTERHOUSE FIVE Themes, Symbols, Motifs, and Construction Themes are the fundamental and often universal ideas explored in a literary work. Alienation may be defined as, among other things, an inability to make connections with other individuals and with society as a whole. In this sense, Billy Pilgrim is a profoundly alienated individual. He is unable to connect in a literal sense, as his being "unstuck in time" prevents him from building the continuous set of experiences which form a person's relationships with others. While Billy's situation is literal in the sense of being a science fiction device—he is "literally" travelling through time—it also serves as a metaphor for the sense of alienation and dislocation which follows the experience of catastrophic violence (World War II) and which is, for Vonnegut and many other modern writers, a fact of life for humanity in the twentieth century. It is appropriate that what is arguably the closest relationship Billy has in the novel is with the science fiction writer Kilgore Trout, another deeply alienated individual: "he and Billy were dealing with similar crises in similar ways. They had both found life meaningless, partly because of what they had seen in the war." One of the most important themes of Slaughterhouse-Five is that of free will, or, more precisely, its absence. This concept is articulated through the philosophy of the Tralfamadorians, for whom time is not a linear progression of events, but a constant condition: "All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist." All beings exist in each moment of time like "bugs in amber," a fact that nothing can alter. "Only on Earth is there any talk of free will." What happens, happens. "Among the things Billy Pilgrim could not change were the past, the present, and the future." Accordingly, the Tralfamadorians advise Billy "to concentrate on the happy moments of life, and to ignore the unhappy ones." What connections does the novel seem to draw between having "character" and having free will? Who are the real characters in the novel, if any? Why is the Tralfamadorian idea of time incompatible with free will? Does Billy Pilgrim exercise his own will at any point in the novel? If so, when? Apathy and passivity are natural responses to the idea that events are beyond our control. Throughout Slaughterhouse- Five Billy Pilgrim does not act so much as he is acted upon. If he is not captured by the Germans, he is kidnapped by the Tralfamadorians. Only later in life, when Billy tries to tell the world about his abduction by the Tralfamadorians, does he initiate action, and even that may be seen as a kind of response to his predetermined fate. Other characters may try to varying degrees to initiate actions, but seldom to any avail. As Vonnegut notes in Chapter Eight, "There are almost no characters in this story, and almost no dramatic confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick and so much the listless playthings of enormous forces." Given the absence of free will and the inevitability of events, there is little reason to be overly concerned about death. The Tralfamadorian response to death is, "So it goes," and Vonnegut repeats this phrase at every point in the novel where someone, or something, dies. Billy Pilgrim, in his travels through time, "has seen his own death many times" and is unconcerned because he knows he will always exist in the past. "Billy told her what had happened to the buildings that used to form cliffs around the stockyards. They had collapsed. Their wood had been consumed, and their stones had crashed down, had tumbled against one another until they locked at last in low and graceful curves. "It was like the moon," said Billy Pilgrim. The destruction of Dresden symbolizes the destruction of individuals who fought in the war, in addition to the millions who died. This destruction of men includes those like Billy Pilgrim who are not able to function normally because of the experience. Time in the novel is subjective, or determined by those experiencing it. For example, the British POWs in Germany, captured at the beginning of the war, have established a “timeless” prison camp. For them, the monotony of daily life has insulated them from history and the war “outside.” On the other hand, Valencia and Barbara, Billy’s daughter, serve to mark “normal,” lived time. Barbara perceives life as linear and is angered by Billy’s claims of a fourdimensional universe. On the alien world of Trafalmadore that all time happens simultaneously; thus, no one really dies. But this permanence has its dark side: brutal acts also live on forever. The Tralfamadorians are pretty clear that their novels hold no moral lessons for readers. After all, what would be the point of a moral lesson when you can't do anything to change the future? Slaughterhouse-Five, with its tiny sections, seems to be imitating a Tralfamadorian novel. So it makes sense that the narrator doesn't spend much time preaching about right or wrong: that's not the point of this book. Vonnegut seems to be asking his readers to do instead is to think about how much human suffering the war brought for both sides. Some of the most evil characters in the book – Bertram Copeland Rumfoord and Paul Lazzaro – are the ones who think they are absolutely right. This kind of righteous self-assurance is what leads to war in the first place. In the first chapter of Slaughterhouse-Five, the narrator promises Mary O'Hare that he will write a novel about World War II that will not attract the attention of manly men like John Wayne or Frank Sinatra. One way in which Vonnegut certainly succeeds in making war seem utterly unappealing (besides, you know, the death and pain and misery) is by emphasizing the hunger and illness of the soldiers fighting it. Paul Lazzaro's stomach is shrunken with hunger, Edgar Derby weeps at the taste of syrup, and all the American POWs spend their first night in the British compound with explosive diarrhea. The book really foregrounds the unattractive, absurd realities of male bodies under stress. The only soldiers with big muscles and washboard abs are the English officers, who have been prisoners for the whole war, and who barely fight Kurt Vonnegut depicts the bodies of the American POWs as weak and poorly fed to demonstrate that this is a war being fought by fools and children rather than heroic manly men. Slaughterhouse-Five is a book about prisoners of war, and it doesn't get much more confined than that. But even more, it's a book about the many, many ways people get trapped: by the army, by family, and by their own beliefs in God or glory. It isn't only the Germans or the U.S. Army who take away Billy's choices. He also finds himself caving in to the expectations of his mother, his optometry office, and even his own daughter. Billy sees very little real freedom in his life, which is perhaps why he is so eager to accept that there is no such thing as free will. The Germans and the Tralfamadorians both take away Billy's freedom, but the Tralfamadorians go a step further by giving him the tools he needs to accept his confinement. Even after Billy is freed from German captivity, he remains mentally a prisoner of his war experiences – until he can replace these memories with life on Tralfamadore. Motif is an object or idea that repeats itself throughout a literary work. In a literary work, a motif can be seen as an image, sound, action or other figures that have a symbolic significance and contributes toward the development of theme. Motif and theme are linked in a literary work but there is a difference between them. In a literary piece, a motif is a recurrent image, idea or a symbol that develops or explains a theme while a theme is a central idea or message. Sometimes, examples of motif are mistakenly identified as examples of symbols. Symbols are images, ideas, sounds or words that represent something else and help to understand an idea or a thing. Motifs, on the other hand, are images, ideas, sounds or words that help to explain the central idea of a literary work i.e. theme. Moreover, a symbol may appear once or twice in a literary work, whereas a motif is a recurring element. Birdsong rings out alone in the silence after a massacre, since no words can really describe the horror of the Dresden firebombing. The bird sings outside of Billy’s hospital window and again in the last line of the book, asking a question for which there is no answer, just as there is no answer for how such an atrocity as the firebombing could happen. The bird symbolizes the lack of anything intelligent to say about war. The phrase “So it goes” follows every mention of death in the novel, equalizing all of them, whether they are natural, accidental, or intentional, and whether they occur on a massive scale or on a very personal one. The phrase reflects a kind of comfort in the Tralfamadorian idea that although a person may be dead in a particular moment, he or she is alive in all the other moments of his or her life, which coexist and can be visited over and over through time travel. The repetition of the phrase keeps a tally of the cumulative force of death throughout the novel, thus pointing out the tragic inevitability of death. Phrase occurs 106 times in the novel. On various occasions in Slaughterhouse-Five, Billy’s bare feet are described as being blue and ivory, as when Billy writes a letter in his basement in the cold and when he waits for the flying saucer to kidnap him. These cold, corpselike hues suggest the fragility of the thin membrane between life and death, between worldly and otherworldly experience. The barbershop quartet made up of optometrists (see sight), sing a sentimental song about old friendship. The experience of watching and listening to them visibly shakes Billy. He remembers the night Dresden was destroyed. The four guards huddled together, and the changing expressions on their faces—silent mouths open in awe and terror—seem to Billy like a silent film of a barbershop quartet. The singing provides Billy with a long-delayed catharsis for the tragedy that he seems to have passively observed in Dresden. In fact, Billy experienced the actual firebombing as no more than the sound of heavy footsteps above the safe haven of the meat locker. Seeing the Febs and remembering the sight of his German guards, Billy is finally able to create an association with the tragedy. Four open-mouthed men signify for Billy the loss of tens of thousands of lives. Realizing this fact allows him to grieve the loss and discuss it openly with Montana Wildhack when she asks for a story. By contrast, when Valencia questions Billy about the war on their wedding night, he tells her nothing because he cannot yet understand his own experience, much less recount it to others. Montana Wildhack wears a locket on which is written, "God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom always to tell the difference” The same words appear framed on Billy's optometry office wall First, the prayer appears in both Billy's real life and his Tralfamadorian life, strongly hinting that his Tralfamadorian experiences are made up. He has taken bits and pieces from things he has seen in his daily life and read in science fiction novels to make up a world he wants to live in. Second, this prayer expresses something profound that Billy is really looking for. He does want to find a way to accept what he cannot change (the past), the courage to change what he can (his current reality), and the wisdom to tell the difference. The narrator describes his own breath when he is drunk as "mustard gas and roses"– which is what his dog, Sandy, specifically does not smell like. This is also the odor of the corpses at Dresden a couple days after the firebombing, which Billy Pilgrim discovers as he digs through the rubble of the city Repetition demonstrates that no part of this story is isolated from any other. Each section, as brief as it may be, fits into a larger consideration of wartime and its aftermath. After the bombing of Dresden, Billy Pilgrim and several POWs return to the slaughterhouse to pick up souvenirs. Billy does not actually spend much time looking for things; he simply sits in a green, coffin-shaped horse-drawn wagon the POWs have been using and waits for his comrades. Billy weeps for the first and last time during the war at the sight of these poor, abused animals As Billy lies in his wagon in the afternoon sun, two German doctors approach him and scold him for the condition of his horses. The animals are desperately thirsty, and in their travel across the ashy rubble of Dresden, their hooves have cracked and broken so that every step is agony. The horses are nearly mad with pain. Given that this scene is the only time Billy cries during the whole war, it must be pretty significant. These horses have no way of understanding the destruction around them, nor the orders being given to them. With no way of protesting their treatment, they obediently keep walking through the ruins of Dresden even though every step on the sharp rocks damages their hooves. Like Billy himself, the animals are innocent victims of great suffering without ever understanding why. The Children's Crusade was a real historical event and also a giant wartime screw-up. Fired up by the religious fanaticism of the day, a boy named Nicholas Cologne inspired thousands of children and teens to march out of France and Germany to go Jerusalem to join the Crusades. It's unclear if any of these kids ever made it to Jerusalem; many turned back and it's likely that most of them died along the journey The Children's Crusade, a pointless sacrifice of innocent life, relates to the novel's anti-war themes. The narrator (Vonnegu) says that he promised the wife of his war buddy that he would call his war book The Children's Crusade so that it would never be misinterpreted as a heroic war story. Billy is an Optometrist Billy’s Job is to find different lenses to help his patient’s see clearly the world around them. Billy/Vonnegut present the reader with different lenses in order to correct the nearsightedness of the world. Show the mistakes and the problems in society Perhaps the most notable aspect of Slaughterhouse-Five's technique is its unusual structure. The novel's protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, has come "unstuck in time"; at any point in his life, he may find himself suddenly at another point in his past or future. Billy's time travel begins early on during the major experience of his life—his capture by German soldiers during World War II and subsequent witnessing of the Allied firebombing of Dresden, Germany. Both the centrality of this event and its radically alienating effect on the rest of Billy's life are represented by the novel's structure. Billy's experiences as a prisoner of war are told in more or less chronological order, but these events are continually interrupted by Billy's travels to various other times in his life, both past and future. In this way, the novel's structure highlights both the centrality of Billy's war experiences to his life, as well as the profound dislocation and alienation he feels after the war. Another unusual aspect of Slaughterhouse-Five is its use of point of view. Rather than employing a conventional thirdperson "narrative voice," the novel is narrated by the author himself. The first chapter consists of Vonnegut discussing the difficulties he had in writing the novel, and Vonnegut himself appears onstage as a character several times later in the novel. Instead of obscuring the autobiographical elements of the novel, Vonnegut makes them explicit; instead of presenting his novel as a self-contained creative work, he makes it clear that it is an imperfect and incomplete attempt to come to terms with an overwhelming event. In a sentence directed to his publisher, Vonnegut says of the novel, "It is so short and jumbled and jangled, Sam, because there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre." Style—the way an author arranges his or her words, sentences, and paragraphs into prose—is one of the most difficult aspects of literature to analyze. However, it should be noted that Slaughterhouse-Five is written in a very distinctive style. In describing overwhelming, horrible, and often inexplicable events, Vonnegut deliberately uses a very simple, straightforward prose style. He often describes complex events in the language one might use to explain something to a child, as in this description of Billy Pilgrim being marched to a German prison camp: A motion-picture camera was set up at the border—to record the fabulous victory. Two civilians in bear-skin coats were leaning on the camera when Billy and Weary came by. They had run out of film hours ago. One of them singled out Billy's face for a moment, then focused at infinity again. There was a tiny plume of smoke at infinity. There was a battle there. People were dying there. So it goes. In writing this way, Vonnegut forces the reader to confront the fundamental horror and absurdity of war head-on, with no embellishments, as if his readers were seeing it clearly for the first time. Black humor refers to an author's deliberate use of humour in describing what would ordinarily be considered a situation too violent, grim, or tragic to laugh at. In so doing, the author is able to convey not merely the tragedy, but also the absurdity, of an event. Vonnegut uses black humor throughout Slaughterhouse-Five, both in small details (the description of the half-crazed Billy Pilgrim, after the Battle of the Bulge, as a "filthy flamingo") and in larger plot elements (Billy's attempts to publicize his encounters with the Tralfamadorians), to reinforce the idea that the horrors of war are not only tragic, but inexplicable and absurd