Governments and Parliaments

advertisement

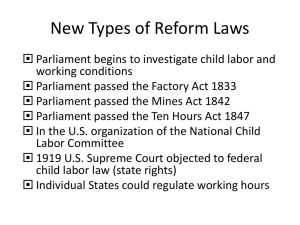

Governments and Parliaments • Two important variables one has to examine in order to understand the power of the government as an agenda setter in parliamentary systems. 1) The first is positional, the relationship between the ideological position of the government and the rest of the parties in parliament. 2) The second is the institutional provisions enabling the government to introduce its legislative proposals and have them voted on the floor of the parliament -the rules of agenda setting. Positional advantages • The government controls the agenda for non-financial legislation because it can associate a vote on a bill with the question of confidence. The parliament is forced to accept the government proposal or to replace the government. • Every government as long as it is in power is able to impose its will on parliament, it does not matter the kind of parliamentary government, whether or not it controls a majority of legislative votes. In more than 50 percent of all countries, governments introduce more than 90 percent of the bills. Moreover, the probability of success of these bills is very high: over 60 percent of bills pass with probability greater than .9 and over 85 percent of bills pass with probability greater than .8. • Even if governments control the agenda, it may be that parliaments introduce significant constraints to their choices. Parliaments can amend government proposals so that the final outcome bears little resemblance to the original bill. Most of the time, neither of these scenarios is the case. Problems between government and parliament arise only when the government has a different political composition from a majority in parliament but such differences are either non-existent, or, if they do exist, the government is able to prevail because of positional or institutional weapons at its disposal • Three possible configurations of the relationship between government and parliament: minimum winning coalition , oversized government and minority government Minimum winning coalition • The most frequent (if we include single party governments in two party systems). The government coincides with the majority in parliament: no disagreement between the two on important issues. The minimum winning coalition represented in government restricts the winset of the status quo from the whole shaded area of the figure to the area that makes the coalition partners better off than the status quo. • If the government parties are weak and include members with serious disagreements over a bill ?, only a marginal possibility because votes are public and party leaders possess serious coercive mechanisms that pre-empt public dissent Minimum winning coalition of A, B and C W(SQ) Oversized coalitions • Oversized majority governments are quite common in Western Europe. In such cases, some of the coalition partners can be disregarded and policies will still be passed by a majority in parliament. Should these parties be counted as veto players, or should they be ignored? • Ignoring coalition partners, while possible from a numerical point of view, imposes political costs: if the disagreement is serious the small partner can resign and the government formation process must begin over again. • Simple arithmetic (Strom argument) disregards the fact that there are political factors that necessitate oversized coalitions. For the coalition to remain intact the will of the different partners must be respected: a departure from the status quo must usually be approved by the government before it is introduced to parliament, and, at that stage, the participants in a government coalition are veto players. Minority governments. • These governments are even more frequent than oversized coalitions. When there are minority governments there is a difference between a governmental and a legislative majority. However according to Tsebelis this difference has no major empirical significance: 1. Governments (whether minority or not) posess agenda setting powers. 2. In particular, minority governments posess not only institutional advantages over their respective parliaments but also have positional advantages of agenda setting Positional Advantages: a memory’s refreshment Z If the agenda setter was more centrally located as regards the other veto players, it could choose best alternatives (and sometimes even its idela point) as Z, that is insed the winset of A and B Consider a five-party parliament in a two dimensional space (A,B,C,D,G) and a minority government G quite centrally located. (E is the multidimensional median) Can government preferences (G) have parliamentary approval ? Any proposal presented on the parliament floor will either be preferred by a majority over G, or defeated by G. A, C, D is a parliamentary majority that can defeat G Also B, C, D is a parliamentary majority that can defeat G The set of points that defeat G are located within the lenses GG’ and GG”. If the parliament is interested in any other outcome and the Government proposes its own ideal point, a majority of MPs will side with the Government. The situation would be tolerable for the government if SQ were moved in the area of these lenses that is close to G, but the hatched areas called X are a serious defeat for the government. However imagine that the SQ is in the the hatched areas. The government G can propose something (SQ1) better just simmetrically located. If the government takes advantage of a closed rule SQ1 will be the final outcome. Institutional Means Of Government Agenda Control 1. the rules to determine the agenda of the plenary 2. the degree of restrictions imposed on the legislature to propose money bills 3. the timing of committee versus plenary involvement in the decision-making process 4. the power of committees to rewrite government bills 5. the rules governing the timetable of committee proceedings 6. the rules curtailing the debate before the final vote in the plenary 7. the maximum lifespan of a bill pending approval http://www.uni-potsdam.de/u/ls_vergleich/Publikationen/PMR.htm Chap 7, p.223-246 Legislation • General hypothesis: policy stability (defined as the impossibility of significant change of the status quo) will be the result of many veto players, particularly if they have significant ideological differences among them. • How to test this hypothesis ? Using a dataset of “significant laws” on issues of “working time and working conditions. • The two issues are highly correlated with the Left-Right dimension that predominates party systems across Europe. • One dimension test of a multidimensional model. • All parties are located along the same dimension: once you identify the two most extreme parties of a coalition, all the others are “absorbed” since they are located inside the core of the most extreme ones. Italian First Republic Example PSI PSDI DC PRI PLI Specific hypotheses to test • The number of significant laws is a declining function of the coalition range, namely the ideological distance of the two most extreme parties in a government coalition. (heteroskedastic relationship) • The number of significant laws will be an increasing function of the distance between the current government and the previous one: the alternation • The number of significant laws will be an increasing function of the government duration Heteroskedasticity Operationalization of significant laws in the selected policy area • Laws (1981-1991) that were in the intersection of both sources (NATLEX from ILO and Encyclopedia of Labor Law) are considered “significant,” while laws existing only in the NATLEX database were considered non-significant. Operationalization of Governments • the variable that matters for the veto players theory is the partisan composition of government. Two successive governments with identical composition should be counted as a single government even if they are separated by an election, which changes the size of the different parties in parliament. • A dataset of “merged” governments, in which successive governments with the same composition were considered a single government regardless of whether they were separated by a resignation and/or an election. Obviously, merging affects the values of duration and the number of laws produced by a government. • Three different sources to calculate (after standardization) government range and alternation (Warwick, Castles-Mair, Laver-Hunt) Operationalization of Governments • Three different sources to calculate (after standardization) government range and alternation (Warwick, Castles-Mair, LaverHunt) Veto Players and incremental legislation • Tsebelis Hypothesis: “Ceteris paribus, significant and nonsignificant laws should vary inversely, because of time constraints. The ceteris paribus clause assumes that the parliament has limited time and uses it to pass legislation (either significant or trivial). • Doering Hypothesis: “government control of the agenda increases the number of important bills and reduces legislative inflation (few small bills). 1. The correlation between all laws and significant laws is negative in two of the three versions of the table, most notably the one that excludes Sweden. 2. Veto players correlated positively with the number of all laws, and negatively with the number of significant laws 3. Agenda control by the government is negatively correlated with legislative inflation. 4. The number of veto players is highly correlated with agenda control