2305-Federalism

advertisement

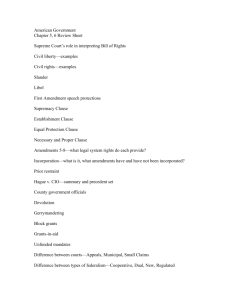

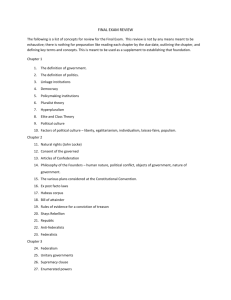

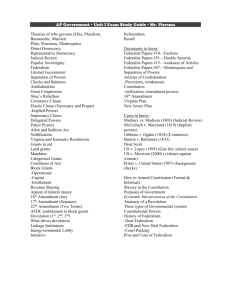

GOVT 2305 Federalism Federalism is the third constitutional principle we cover in this class. As with the others, it involves the division of power within government. Officially this refers to the division of government into two levels: the national and the state. Unofficially, it also includes a third level, local government, which can be a city, county or a single purpose government. Local governments are not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution. States, as part of their reserved powers, have the authority to pass laws allowing groups of individuals to pass laws regulating their interrelations. American government is actually composed of thousands of distinct governments layered one upon the other. Here’s a list based on 2007 figures. National – 1 State – 50 Counties – 3034 Municipalities – 19,429 Township – 16, 504 School Districts – 13, 506 Special Districts – 35,052 That’s a lot. What are these things? What is a nation anyway? The concept of a nation is not that old. The Treaty of Westphalia (1648) Created the modern nation state with sovereign authority within its borders. Wikipedia: Country Federalism is an Accidental Principle The American Federal system grants sovereignty to two levels of government. This was not an anticipated outcome of the Constitutional Convention. The division between the national and state level was the result of the compromise in the constitutional convention dubbed “The Great Compromise.” You might want to look through a couple of web resources: First, Wikipedia’s: Federalism in the United States. The second link is to Wikipedia’s category page on Federalism Case Law. This takes you to various other pages with information about major court cases which have ruled on disputes associated with federalism. A federal system is different than a unitary or confederated. In the former sovereignty rests fully in the upper level, in the latter it is in the lower level. Unitary, Federal, and Confederated Systems Unitary: The national government dominates and the states exist as administrative units only. This is the relationship that exists between the state of Texas and the 254 counties. They have little independent authority and implement state laws. Confederacy: The states possess sole sovereign authority and a weak central authority exists to mediate disputes between them. They have no real authority over the states. The Articles of Confederation The Southern Confederacy Two components of the Articles of Confederation make this explicit: The Articles of Confederation Article II. Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled. The Articles of Confederation Article III. The said States hereby severally enter into a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defense, the security of their liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretense whatever. The theoretical idea behind federalism is that each level of government can best perform certain functions and that responsibility for these functions should be divided accordingly. Recall that the Constitutional Convention was called by those who were concerned that the states, under the Articles of Confederation, were unable to adequate provide for their commercial and security needs. These had to be provided uniformly across the states. Broad – national – interests (as defined by the federalists) were to be provided by the national government. These are listed in Section Eight of Article One of the Constitution – this will be covered more thoroughly below. Here’s a succinct graphic that outlines the powers of the state and national governments. Notice that some powers are shared by each. Some terminology would be helpful here: Delegated (Enumerated) Powers: Power specifically give to the national government. Reserved Powers: Powers (unstated) granted to the states. Concurrent Powers: shared by each level of government. Here is a more exhaustive list of the powers held by each level of government. National Power Internal improvements Subsidies Tariffs Disposal of public lands Immigration law Centralized National Defense Foreign policy Copyrights Patents Currency State Power Property law Estate and inheritance law Commerce laws of ownership and exchange Banking and credit laws Labor and union laws Insurance laws Family laws Morals laws Occupations and professions laws State Power (continued) Public health and quarantine laws Public works laws, including eminent domain Building codes Corporations law Land use laws Water and mineral resource laws Judiciary and criminal procedure laws Electoral laws, including parties Local government laws Civil service laws Local Governments Variances (adaptation of state law to local conditions) Public works Contracts for public works Licensing of public accommodations Assessable improvements Basic public services A general term used to describe the powers granted to the states and by extension local government is “police powers.” police power is the government to regulate behavior and enforce order within their territory for the betterment of the general welfare, morals, health, and safety of their inhabitants. Its generally stated that local governments perform “house keeping” functions for communities. They keep things neat, tidy and safe: Sewage, drainage, street repair, stuff like that. Local governments can take a variety of forms: City, county, multi purpose, single purpose. Federalism also involves regional governments as well In Texas these are called Area Councils of Government, they attempt to coordinate activities within the governing entities in a particular area. The local region is located in the Houston-Galveston Area Council A dispute: What should the balance be between national power sand state power? Centralism vs Decentralism What are the advantages and disadvantages of centralized control and coordination? A centralized structure can offer efficiency in how functions are provided, but they tend to be “topdown” organizations. Decisions made at the top may not necessarily be well connected to the needs at the bottom. From the Cato Institute, a paper asking what sorts of regulations are best handled on the federal level. What are the advantages and disadvantages of de-centralized control and coordination? It’s the opposite of the centralized model. They are bottom-up, meaning that services and functions can be finely tuned to the needs of specific regions, but the over all structure can be chaotic and inefficient. One argument in favor of granting greater flexibility to state and cities is that they can serve as “laboratories of democracy.” AEI: Laboratories of Democracy. States can experiment with different ways to solve problems. Some will succeed, some will fail. Each will provide lessons about what to do and not do in order address a given policy problem: education for example, or prison policy. This assumes that we can’t really solve certain problems on paper – we can only try different options and see what works best objectively. Note: Nations, states and cities are distinct units. The nation and the states are political units primarily. They possess sovereign power, traced to the people. Local governments are primarily economic units. They are not sovereign entities. A city begins as an economic enterprise first, and achieves political status afterwards. This is not true for counties. A county is the administrative arm of the state. It is responsible for basic services to non-city residents and for the provision of certain state functions. In Texas counties are responsible for: - issuing state automobile licenses, among other licenses issued by the state - voter registration - conduction of elections - property tax assessment and collection - maintaining vital records: birth and death certificates - conducting health and welfare programs Controversy: What is the legal status of cities, since that is not established in the Constitution? There are two conflicting theories about the status of cities. One is Dillon’s Rule, the other is the Cooley Doctrine. Dillon’s Rule Municipal corporations owe their origin to, and derive their powers and rights wholly from, the legislature. It breathes into them the breath of life, without which they cannot exist. As it creates, so may it destroy. If it may destroy, it may abridge and control Cooley Doctrine Local government is a matter of absolute right; and the state cannot take it away. The argument was made in a concurring decision in a court case, which does not make it binding. In the United States, Dillon’s Rule predominates. A city is subject to control by the state, although solvent, powerful cities are generally autonomous for all practical purposes. Non-solvent cities can be taken over by states, though critics argue that it undermines democratic self determination. City governments need charters issued by the states in order to govern. There two general types: General Law Home Rule General Law General law cities are smaller cities whose powers are limited; they operate according to specific state statutes that define their powers and duties. They are restricted to doing what the state directs or permits them to do. If a general law city has not been granted the express or implied power by the state to initiate a particular action, none may be taken. Home Rule Home rule cities are cities with populations of more than 5,000 in which citizens have adopted home rule charters. A charter is a document that establishes the city’s governmental structure and provides for the distribution of powers and duties among the various branches of government. In order to be implemented, the charter must be approved by the people at an election. Likewise, changes in the charter must be approved by a vote of the people. The legal position of home rule cities is the reverse of general law cities. Rather than looking to state law to determine what they may do, as general law cities must, home rule cities look to the state constitution and state statutes to determine what they may not do. Thus, if a proposed home rule city action has not been prohibited or pre-empted by the state, the city generally can proceed. We discuss this concept more thoroughly in GOVT 2306. Let’s look at federalism from a constitutional perspective. Ongoing controversy exists over how precisely the divisions between national and state powers ought to be can be drawn, or whether these powers are shared to some degree. A contemporary description: Should the relationship between the national and state governments be like a layer cake or a marble cake? Ought there be an intermingling of functions between the national and state governments? Layer cake federalism is the relationship between the central government of a nation and that of its states, where the powers and policy assignments of the government hierarchy ("layers" of government) are clearly spelled out and distinct from one another. This form of federalism is also called Dual Federalism. In other words, the national government deals with the issues that are national and the states deals with the state and local issues. Ideally, there will be no interference between the two arenas. Marble Cake Federalism is a form of federalism where there is mixing of powers, resources, and programs between and among the national, state, and local governments. Federalism is a system of government in which power is divided between a central government and regional or sub-divisional governments. In marble cake federalism there will be an intermingling of all levels of government in policies and programming. This is also known as co-operative federalism. Remember that Madison and Hamilton presented plans to the Constitutional Convention which would have established unitary systems of government. Hamilton’s Plan Madison’s Plan Both proposed a national government far stronger than the states. The national government could appoint state governors and veto state laws. They were unsuccessful in doing so. The plans were rejected. A sufficient number of delegates supported state power to force a compromise. The Great Compromise Establishes the principle of dual sovereignty. This was one of the several compromises in the national government that we discussed previsouly. The national government is connected both to the people (through the House of Representatives) and the states (through the Senate). The state and national governments therefore are equal. This is a very tricky relationship that inevitably lead to conflict. Its tough to have two bosses. Among the questions raised: What role should each level play in governing? Was there a clear intent established by the authors of the Constitution that must be maintained? Or is the relationship meant to be dynamic? These are still dominant questions today. Consider the ongoing conflict between the state of Texas and the US government over multiple issues. The Civil War was fought, in many ways, to resolve questions over the relative power of each level of government. More on this below. Several Federalist Papers focused on the relative powers of the national and state governments, and the question whether the power of the national government would interfere with that of the states. Federalist #39 addresses whether the federal plan in the Constitution is still a republic. Since all powers are ultimately based on the people, he argues that it is. Federalist #40 argues that the members of the convention did not violate their mission by creating a federal system. Federalist #41 outlines the general powers that were considered to be necessary to grant to the national government. That we may form a correct judgment on this subject, it will be proper to review the several powers conferred on the government of the Union; and that this may be the more conveniently done they may be reduced into different classes as they relate to the following different objects: 1. Security against foreign danger; 2. Regulation of the intercourse with foreign nations; 3. Maintenance of harmony and proper intercourse among the States; 4. Certain miscellaneous objects of general utility; 5. Restraint of the States from certain injurious acts; 6. Provisions for giving due efficacy to all these powers. Federalist #42 details why foreign power (treaty making, the regulation of foreign commerce, etc…) as well as the regulation of interstate commerce needs to be given to the national government. Federalist #43 defines what the term miscellaneous powers refers to. Federalist #44 details and justifies the restrictions placed on state powers. These points culminate in a broad argument in Federalist #45 about the relationship between national and state powers. Key Quote: The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the federal government, are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State governments are numerous and indefinite. The former will be exercised principally on external objects, as war, peace, negotiation, and foreign commerce . . . The powers reserved to the several States will extend to all the objects which, in the ordinary course of affairs, concern the lives, liberties, and properties of the people, and the internal order, improvement, and prosperity of the State. What does this mean? Few and Defined: The powers delegated to the national government in Section Eight of Article One and implied in the General Welfare, Commerce, and Necessary and Proper Clauses. These are either enumerated, meaning that they are clearly listed in the document, or implied, meaning that they are assumed to be loosely based on the enumerated powers. Numerous and Indefinite: The states have the reserved powers, meaning in essence everything else. A we will see further below, the logic used in the federalist papers to describe the relationship between the state and national governments would be radically transformed by the Civil War th amendments – notably the 14 . The principle change was that citizens of the state were officially recognized as being citizens of the United States. States could no longer treat American citizens unequally, nor deny to them the privileges and immunities guaranteed in the US Constitution. Transformations have also occurred as a result of loose interpretations of certain clauses within the Constitution. This transition begins during the New Deal. More on this below. Now we should spend a moment describing the various powers described above, as well as other related to federalism. This will help us understand the changes that have occurred over American history that have led to a larger national government than once existed. Here are key terms related to the types of powers that exist: Delegated Enumerated Expressed Reserved Implied Inherent The Delegated Powers The Delegated Powers -- also called the enumerated or the expressed powers (these terms are often used interchangeably)-- are those clearly written, and listed, in the Constitution and granted to Congress. Its what Congress has the authority to write laws about. I tend to use the term delegated powers because that’s the word used in the 10th Amendment. The term enumerated refers to the fact that these powers are provided in a list. Generally these powers fall into two broad categories: commercial and military. Whatever is clearly listed is considered to be a delegated power. Remember that these powers were the ones Federalist were most concerned about securing. These were not secure under the Articles of Confederation. Here is an important qualifier: There is no general power regarding commerce and the military, rather there are specific enumerated powers pertaining to different aspects of each. Article One, Section Eight This is the part of the Constitution where those powers are listed. Let’s look through them. Commercial powers first: To borrow money on the credit of the United States; To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes; To establish a uniform Rule of Naturalization, and uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States; To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures; To provide for the Punishment of counterfeiting the Securities and current Coin of the United States; To establish Post Offices and Post Roads; To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries; To constitute Tribunals inferior to the supreme Court; Here’s a key assumption underlying these powers, it is the idea that the national government is in a better position to regulate these things because they ought be common across the states. Here’s a question we will consider as we go through this section. As the economy develops, what other functions ought to – or ought not to – be similarly regulated on the national level? Now for the military powers: To define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and Offenses against the Law of Nations; To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water; To raise and support Armies, but no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years; To provide and maintain a Navy; To make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces; To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions; To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress; Here is a key assumption underlying these powers being given to the national government. Defense is a national matter. If left to the state there is little reason to believe that there coordinated efforts to defend the nation. Articles 2 and 3 also contain certain powers that were granted to the executive and the judicial branches. These will be covered more fully when we cover those articles soon enough. Article 2 enumerates certain expressed powers for the president. These will be expanded on in an upcoming section. The powers are of two sorts: those exercised alone without legislative approval and those that require consent of the Senate or House. Powers of the President Alone: commander in chief of the armed forces; commission officers of the armed forces; grant reprieves and pardons for federal offenses (except impeachment); convene Congress into special session; receive ambassadors; take care that the laws be faithfully executed; make use of the "executive power" of the office; appoint officials to lesser offices. Powers shared with the Senate/House: make treaties; appoint ambassadors, judges, and high governmental officials; approve legislation. Some of these powers can be very controversial, notably the commander in chief powers. Are there any limits to this power? Once the US is at war, what limits can be placed on the president’s decisions? Are a great many additional powers (surveillance, detention, targeted killings) inherent within the commander in chief powers? Related to the concept of inherent powers is the term “plenary powers.” This refers to full powers granted to an individual or institution. This type of power cannot be checked, which makes it problematic for an obvious reason. Article 3 similarly defines the powers of the Judiciary. It primarily states what the jurisdiction of the nation courts are. Again, more on this when we look at the Judiciary. There is a related category called the restricted powers. There are two clauses in the Constitution that clearly restrict powers on the part of the national and state governments. The Constitution places few clearly defined restrictions on the powers of the national government. It also mandates the national government be neutral towards the states. Policies cannot benefit one at the expense of the others. These are found in Article One, Section Nine 1. The migration or importation of such persons as any of the states now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the year 1808, but a tax or duty may be imposed on such importations, not exceeding 10 dollars for each person. 2. The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it. 3. No bill of attainder or ex post facto law shall be passed. 4. No capitation, or other direct tax shall be laid unless in proportion to the census or enumeration herein before directed to be taken. (Modified by Amendement XVI) 5. No tax or duty shall be laid on articles exported from any state. 6. No preference shall be given by any regulation of commerce or revenue to the ports of one state over those of another: nor shall vessels bound to, or from one state, be obliged to enter, clear, or pay duties in another. 7. No money shall be drawn from the treasury but in consequence of appropriations made by law; and a regular statement and account of the receipts and expenditures of all public money shall be published from time to time. 8. No title of nobility shall be granted by the United States: And no person holding any office or profit or trust under them, shall, without the consent of the Congress, accept of any present, emolument, office, or title, of any kind whatever, from any king, prince, or foreign state. The Reserved Powers When we discussed the Constitutional Convention, we mentioned that despite the fact that Federalists wanted to strengthen the national government, forces were also interested in ensuring that states were able to maintain authority in certain areas. Article 1, Section Ten contains specific limitations on the power of the state governments. These limits are intended to ensure that the state do not assume any power that is national in scope. Article 1, Section 10, Clause 1 No State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation; grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal; coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts; pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts, or grant any Title of Nobility. Article 1, Section 10, Clause 2 No State shall, without the Consent of the Congress, lay any Imposts or Duties on Imports or Exports, except what may be absolutely necessary for executing it's inspection Laws: and the net Produce of all Duties and Imposts, laid by any State on Imports or Exports, shall be for the Use of the Treasury of the United States; and all such Laws shall be subject to the Revision and Control of the Congress. Article 1, Section 10, Clause 3 No State shall, without the Consent of Congress, lay any Duty of Tonnage, keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace, enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State, or with a foreign Power, or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay. The attendees at the convention did not see the need to explicitly state what the power of the states were regarding what types of laws they could pass, but such language was included in the Bill of Rights. It became the 10th Amendment. “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” Notice that the amendment refers also to the powers reserved to the people, not only the states. We’ll dig into that some other time. This part of the amendment also overlaps the content of the Ninth Amendment. More on that in the next section. The reserved powers are argued to refer to the police powers. These are laws that related to the health, welfare, safety and morals of a community. As with the quote from Federalist #45 referred to previously, it implies that the powers of the states are more vast than those of the national government. While the 10th Amendment is commonly referred to in political contexts, it has not been used often in court cases. Click here for the Tenth Amendment Center for an example of a political group focused on the amendment. One example of a recent court case invoking the 10th Amendment is Printz v US, where parts of the Brady Bill were found unconstitutional since it mandates that state officials carry out federal law, in this case background checks on handgun purchasers. Disputes between the national and state governments are usually based on other parts of the Constitution – notable the implied powers which we will be discussing below. Texas is commonly at the center of Tenth Amendment disputes. Interests that can dominate the state government are often unable to dominate the national government. Conflict is inevitable. Much of the conflict centers on whether the reserved powers are immune from any interference from the national government. One of the delegated powers of the national government is the ability to regulate commerce between the states. The reserved powers are assumed to be those that are fully intrastate. They have no impact on what happens in other states. Is something that happens in one state has an impact on another, it is argued that the national government has jurisdiction over it. But this is controversial since it can be argued that almost anything that happens in a state can have an impact beyond its borders. This is especially true since technology allows for rapid communications and transportation. Certainly more rapid than existed when the Constitution was written. The Implied Powers This is the most controversial of the powers since it is the most flexible and subject to reinterpretation. The Implied Powers are the powers the are considered necessary in order to carry out the delegated powers. These tend to be based on what are called the “elastic” clauses. These include: The Taxing and Spending Clause The Commerce Clause The Necessary and Proper Clause The expansion of national power over the course of time has been driven by expanded reinterpretations of these parts of the Constitution. A great many Supreme Court cases have involved challenges to whether laws are in fact based on constitutional language. For example, the recent Supreme Court case over the ACA (Obamacare) justified it based on the taxing and spending clause. Since the relationship between the national and state governments is due to interpretations of the Constitution, the Supreme Court is responsible for determining the nature of federalism. But this can be highly controversial. Nearly two centuries ago, Chief Justice Marshall observed that “the question respecting the extent of the powers actually granted” to the Federal Government “is perpetually arising, and will probably continue to arise, as long as our system shall exist.” – John Roberts. The Taxing and Spending Clause Article 1, Section 8, Clause 1 The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States. For further info: Findlaw Cornell This – obviously – refers to the power to raise revenue and to then spend it. But this is not as simple as it may seem. Taxes can do many other things in addition to raising revenue. Taxes can be used to regulate commerce, to encourage or prohibit behavior, or to protect domestic industry , in addition to other things. The related power to spend can also be used to encourage the states to adopt certain policies. Drinking ages, medical services for the poor etc… This is especially controversial when tied into the General Welfare Clause. How narrowly or broadly should this clause be read? This was a place where the fight between Madison and Hamilton over whether the Constitution should be strictly or loosely interpreted played out. Does the General Welfare Clause grant an independent power for Congress to spend money on any matter related to the general welfare of the people so long as it does not favor one region or group over another? Or does spending still have to be tied directly to a grant of power within the Constitution? This was a major controversy early in American history – one that still reverberates today. Limited interpretations of the rule were common prior to until 1937. Example: The Child Labor Tax Law of 1919 was found unconstitutional because its was intended primarily to regulate child labor. In 1936 – in US v Butler - a tax on companies that processed farm products that was designed to maintain crop prices was found unconstitutional. But this limited view would change in 1937. The principle transition in this clause occurred during the New Deal after the Social Security Act was passed and was subsequently challenged in court. The case was Helvering v Davis. The court ruled that the act was constitutional under the General Welfare Clause. - the full story from SSA Online. From the decision: “Congress may spend money in aid of the "general welfare." Constitution, Art. I, section 8; United States v. Butler, 297 U.S. 1, 65; Steward Machine Co. v. Davis, supra. There have been great statesmen in our history who have stood for other views. We will not resurrect the contest. It is now settled by decision. United States v. Butler, supra. The conception of the spending power advocated by Hamilton and strongly reinforced by Story has prevailed over that of Madison, which has not been lacking in adherents. Yet difficulties are left when the power is conceded. The line must still be drawn between one welfare and another, between particular and general. Where this shall be placed cannot be known through a formula in advance of the event. There is a middle ground, or certainly a penumbra, in which discretion is at large. The discretion, however, is not confided to the courts. The discretion belongs to Congress, unless the choice is clearly wrong, a display of arbitrary power, not an exercise of judgment. This is now familiar law.” The opinion states that the problem of old age poverty is national in scope and the solution offered in the SSA is also national in scope. So it fits under the general welfare clause. In the 1960s, this logic would also justify amending the Social Security Act to provide for medical assistance for the elderly (Medicare) and the poor (Medicaid) These were two of many programs launched during The Great Society, which was the name used to describe policies that aggressively attempted to eradicate poverty and the circumstances that created them. The Supreme Court’s recent decision on the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act – Obamacare – was based on similar reasoning. In the majority decision, John Roberts explicitly argued that the act was not constitutional under the Commerce or Necessary and Proper Clauses, but was so under the Taxing Clause. “....it is abundantly clear the Constitution does not guarantee that individuals may avoid taxation through inactivity. A capitation, after all, is a tax that everyone must pay simply for existing, and capitations are expressly contemplated by the Constitution. The Court today holds that our Constitution protects us from federal regulation under the Commerce Clause so long as we abstain from the regulated activity. But from its creation, the Constitution has made no such promise with respect to taxes.” But an additional part of the act was not found to be authorized under the Spending clause. The requirement that states must expand Medicaid or risk losing existing Medicaid funding was judged to be coercive. The Necessary and Proper Clause Article 1, Section 8, Clause 18 “The Congress shall have Power To . . . make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.” More Background Findlaw Critical Dispute: What does “necessary and proper” mean? Does it refer to any power that is useful to government’s ability to carry out a delegated power? Or does it only refer to those powers that are essential to it? As with other constitutional matters, the Hamiltonians argued for a loose reading while the Jeffersonians argued for a loose reading. Early example: The Debate over a National Bank. A national banks was argued by Hamilton to fall under the clause because the bank would help the national government carry out its commercial and currency powers. You might get something out of looking at these lessons plans regarding the battle over the bank. And also commentary on the subject made by Justice Story. Hamilton’s position would be accepted in McCulloch v. Maryland. For a fuller discussion of cases involving the necessary and proper clause, click here for a link to findlaw.com. But decades later President Andrew Jackson would argue that these powers could be carried out by the Treasury Department without a National Bank. The bank was not essential to carrying out the delegated powers. Click here for his veto message regarding the bank which outlines this view point. Recent cases involving the Necessary and Proper Clause United States v Comstock The court agreed that the necessary and proper clause authorized commitment of people deemed “sexually dangerous” after they fulfilled their sentences National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius The court did not see a constitutional justification for the ACA based on the Necessary and Proper Clause because the power was not “proper.” Here’s commentary about Robert’s ruling on the Necessary and Proper Clause and the ACA. The Commerce Clause The Commerce Clause: “The Congress shall have Power To . . . regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes;” Links regarding the Commerce Clause Legal Information Institute Wikipedia FindLaw Exploring Constitutional Conflicts This was one of the enumerated powers, but over time questions have been raised about the full meaning of the word “commerce” and what it in fact takes to regulate commerce between the states. A handful of disputes have existed regarding this clause. An early one concerned whether states could regulate interstate commerce? According to Gibbon v Ogden (1824), no. A state could not prevent an individual licensed by the national government from engaging in interstate commerce. Licensing for interstate commerce must be a national function in order to ensure that licenses, and commercial rules in general, are consistent across the country. During the bulk of the 19th Century, the powers of the national and state government were distinct, but as technology improved, commercial relations between the state began to increase and expand. Beginning in the 1880s, Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, national institutions had been established that began interfering with state sovereignty. Some laws were found unconstitutional, but not all of them. The Sherman Anti-Trust Act was found constitutional in Swift v US, and the court ruled that the national government had the power to regulate local economic activity if it was related to interstate economic activity. The principle change in the definition of the commerce clause was driven by progressives in the late 19th century. Does “commerce” mean trade in finished products, or does it also mean the manufacturing and labor involved in creating those products? The Progressive Era For decades the Supreme Court defined commerce in a limited manner. This led to a variety of laws aimed at addressing social problems on a national level being found unconstitutional. “In our view the necessary effect of this act is, by means of a prohibition against the movement in interstate commerce of ordinary commercial commodities to regulate the hours of labor of children in factories and mines within the states, a purely state authority.” A real shift did not occur until the New Deal The New Deal The “New Deal” is the term given to a series of laws passed in the wake of the Great Depression that granted addition powers to the national government on the premise that states were not able to effectively handle the emergency. The New Deal necessitated a reinterpretation of constitutional language, notable the definition of the word: “commerce” During FDR’s first term, the Supreme Court did not find New Deal legislation constitutional. They held a rigid view of commerce. Found unconstitutional: National Industrial Recovery Act in Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States This led to a conflict between the executive and judicial branches that came to a head in the court packing scheme. In order to resist the effort to add new members to the court, the court began reversing its opinions of certain New Deal policies. The key switch was by Justice Owen Roberts. The two most consequential cases: National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel 1937 - The Wagner Act, which authorized the national government to force corporations to recognize labor unions was found constitutional because labor was included in the definition of commerce. Wickard v. Filburn 1942 - The concept of interstate commerce was expanded to allow for national regulation of intrastate activity if intrastate activity affects interstate activity. Over the past century the size of the national government, and the scope of its powers, has increased significantly. This has required a rethinking of the proper role of each level of government and the reinterpretation of constitutional language justifying it. It has also been highly controversial. States tend to not like federal encroachments on what they see as their sovereign power, but minorities in state citizens often feel undeserved by the state government and seek redress on the national level. For almost 60 years no major piece of legislation regarding the commerce clause that allowed for an expansion of national power was found unconstitutional. This was due at least in part to Democratic successes in presidential elections. Many of these policies placed the national government in a cooperative relationship with the states and local governments. The national government would establish an objective and encourage the states to go along. Often these are implemented with matching grants. The national government would encourage the states to engage in certain endeavors by matching state dollars with federal dollars. One of the first area projects funded with matching federal dollars was the dredging of the Port of Houston. Interstate Highway System primarily built with a mix of 90% FHWA funds from the Highway Trust Fund and 10% matching state DOT funds. Other Examples of Such Policies: Welfare Education Transportation Health Care The states have been encouraged to develop certain programs which focus on issues of national concern – but had previously been thought to fall fully under the reserved powers – by providing funding to encourage states to do so. Some researchers have called this the era of Cooperative Federalism. The national and state governments co-operated on issues of mutual concern. This replaced the era of Dual Federalism where each level of government worked independently on its own issues in isolation of the others. Whereas the relationship between the national and state governments previously had resembled a layer cake, they suddenly resembled a marble cake. In the 1960s, the use of these grants, specifically categorical grants, led researchers to coin the term “regulated federalism” because the national government was now in a position to pressure the state to follow federal guidelines or risk losing federal funds. Click here for a brief description of the stages of federalism. More recently (beginning in the mid – 1990s) court cases have ruled against further uses of the Commerce Clause to expand national power. There have been efforts to halt, or possibly roll back the expansion of the national government, by reinterpreting constitutional language as it had been prior to the New Deal. The Constitution in Exile movement. Researchers have called this effort New Federalism, which is an attempt to transfer powers back to the states – the fancy term for this effort is devolution. Some supporters want to go further and privatize certain government functions completely. This is part of a broader effort to minimize the scope of government generally and the national government specifically. These shifts have involved reversing the Supreme Court’s attitude towards things like commerce. The first indication that a shift might be underway was the decision by the court to not find the Gun Free Schools Zones Act constitutional on the basis of the Commerce Clause. United States v. Lopez 1995 - The Supreme Court rejected the argument that the national government could pass a law based on the commerce clause. They rejected the idea that the federal government could outlaw gun possession near school zones because it had a suppressing effect on commercial activity. Gun Free School Zones Act was judge to be unconstitutional because it did not directly impact economic behavior – it only indirectly did so. In addition, the activity was judged to be local in nature. “The Lopez court stated that Congress may regulate (1) use of the channels of interstate commerce, (2) the "instrumentalities" (for example, vehicles) used in interstate commerce, and (3) activities that substantially affect interstate commerce.” A second: United States v. Morrison 2000- The Supreme Court rejected the argument that a national law allowing women to sue those who physically attack them was justified since such activity interfered with economic activity. It focused on the civil rights remedy of Violence Against Women Act. These and other cases indicated an effort to roll back the scope of national power under the commerce clause, but the decision in Gonzales v. Raich complicated this. Gonzales v. Raich 2005 – the Supreme Court reaffirmed the constitutionality of the national Controlled Substances Act and its supremacy over California’s Compassionate Use Act. “This activity was the result of the belief that federal law preempted that of California. The government argued that if a single exception were made to the Controlled Substances Act, it would become unenforceable in practice. The government also contended that consuming one's locally grown marijuana for medical purposes affects the interstate market of marijuana, and hence that the federal government may regulate—and prohibit—such consumption. “ - click here for a summary of the various decisions. Current questions involve the potential constitutionality of the Health Care Law. Are challenges to the Health Care Law offering an opportunity to roll back the commerce clause? The court ultimately ruled that the ACA regulated inactivity. People cannot be forced into the commercial sector in order to regulate it. Here’s commentary about Robert’s ruling on the Commerce Clause and the ACA. A few notes on the 14th Amendment. The relationship between the national government and the states was greatly affected by the th 14 Amendment. The 14th Amendment nationalized citizenship and denied states the ability to deny their privileges and immunities. Relevant Text: “Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States . . .” This text will later allow the national government the opportunity to allow those who feel they have been discriminated against the ability to challenge that discrimination in a federal court. Also relevant: “ . . . nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Both of these phrases grant national over the states. Prior to the 14th Amendment, the restrictions on legislative powers spelled out in the First Amendment – such as the free exercise of religion – only limited national power, not state power. This changed gradually after the 14th Amendment when various cases were brought to court ultimately forcing the Supreme Court to consider whether limits on the national government applied to state governments as well. This nationalized the Bill of the Rights by applying it to the states piece by piece. The process has been called the Selective Incorporation of the Bill of Rights to the States. This will be discussed more fully soon. An early case that raised this question was United States v. Cruikshank, "We have in our political system a government of the United States and a government of each of the several States. Each one of these governments is distinct from the others, and each has citizens of its own who owe it allegiance, and whose rights, within its jurisdiction, it must protect. The same person may be at the same time a citizen of the United States and a citizen of a State, but his rights of citizenship under one of these governments will be different from those he has under the other." Here’s an example of a specific case: the guarantee of freedom of speech was incorporated against the states in the case of Gitlow v. New York The requirement of equal protection has allowed the national government – at least in theory – to be a resort for citizens who feel that the states have discriminated against them Study Guide - What are the delegated, reserved and implied powers? Give examples? Where do they come from? What controversies exist about them? - Be familiar with the various issues associated with the commerce clause. - How does federalism impact sovereignty in the United States? What other relationships can exist between state and national governments? - What is the difference between a nation, a state and a city? - What Supreme Court cases have affected the relationship between the national and state government? Be familiar with that impact. - What impact did the 14th Amendment have on the relationship between the national and state governments? - What is the Constitution in Exile movement? - What is an inherent power and why are these controversial? - What are the types of powers that are explicitly granted to the national government? - What limits are placed on the powers of the state? - What factors led to the division of government in the United States to the nation and the states? -What is the source of the powers of cities and local governments? - What is the consequence of loose and strict interpretations of the Constitution? Which parts of the Constitution are most subject to loose interpretations and what have been the consequences of this? - What early disputes existed over the scope of national powers? What court cases helped resolve these issues? - What different – separate - functions do national, state and local governments generally serve? An example of unconstitutional legislation: The Keating-Owen Act of 1916, which outlawed child labor, was found unconstitutional in Hammer v. Dagenhart.