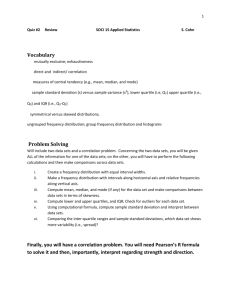

statistics for business - E

advertisement

STATISTICS FOR BUSINESS

UNIT I : Meaning and Definition of Statistics – Collection of data –– Primary and Secondary Classification and Tabulation – Diagrammatic and Graphical presentation Measures of Central

tendency – Mean, Median, Mode, Geometric Mean and Harmonic Mean – simple problems

UNIT II : Measures of Dispersion – Range, Quartile Deviation, Mean Deviation, Standard

Deviation and Co-efficient of Variation. Skewness – Meaning – Measures of Skewness – Pearson’s

and Bowle’s co-efficient of Skewness.

UNIT III : Correlation –Meaning and Definition –Scatter diagram, Karl Pearson’s co-efficient of

Correlation, Spearman’s Rank Correlation, Co-efficient of Concurrent deviation. Regression

Analysis – Meaning of regression and linear prediction – Regression in two variables – Uses of

Regression

UNIT IV : Time Series – Meaning, Components and Models – Business forecasting – Methods of

estimating trend – Graphic, Semi-average, Moving average and Method of Least squares – Seasonal

Variation – Method of Simple average. Index Numbers – Meaning, Uses and Methods of

construction – Un-weighted and Weighted index numbers – Tests of an Index number – Cost of

living index number.

UNIT V : Interpolation: Binomial, Newton’s and Lagrange methods. Probability – Concept and

Definition – Addition and Multiplication theorems of Probability (statement only) – simple

problems based on Addition and Multiplication theorems only

Books Recommended:

1. Statistical Methods by S.P. Gupta

2. Business Mathematics and Statistics by P. Navaneetham

3. Statistics by R.S.N. Pillai and V. Bagavathi

4. Statistics-Theory, Methods & Application by D.C. Sancheti and V.K. Kapoor

5. Applied General Statistics by Frederick E.Croxton and Dudley J. Cowden

UNIT I

CONTENTS

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Meaning and Definition of Statistics

Collection of data

Primary and Secondary

Classification and Tabulation

Diagrammatic and Graphical presentation

Measures of Central tendency

Mean, Median, Mode, Geometric Mean and

8. simple problems

Definition of Statistics

“statistics are the numerical statement of facts capable of analysis and interpretation and

thescience of statistics is the study of the principles and the methods applied in collecting,

presenting, analysis and interpreting the numerical data in any field of inquiry.”

Limitation of statistics

The important limitations of statistics are:

(1) Statistics laws are true on average. Statistics are aggregates of facts. So single observation is

not a statistics, it deals with groups and aggregates only.

(2) Statistics does not deal with qualities: Statistical methods are best applicable on quantitative

data.

(3) All the values should not be the same. The values in statistics have to be different. When the

amount of sales in different periods are considered they will not be equal. The daily production in

the factory will not be the same. In statistics, the observation differ from one another.

(4) If sufficient care is not exercised in collecting, analyzing and interpretation of the data, statistical

results might be misleading.

(5) Only a person who has an expert knowledge of statistics can handle statistical data efficiently.

(6) Some errors are possible in statistical decisions. Particularly the inferential statistics involves

certain errors. We do not know whether an error has been committed or not.

(7) Statistical results are not exact: The statistical results are not exact as in natural Sciences.

Statistical forecast using time series or regression do not coincide with true values.

Statistical Data

A sequence of observation, made on a set of objects included in the sample drawn from population

is known as statistical data.

(1) Ungrouped Data:

Data which have been arranged in a systematic order are called raw data or ungrouped data.

(2) Grouped Data:

Data presented in the form of frequency distribution is called grouped data.

Collection of Data:

The first step in any enquiry (investigation) is collection of data. The data may be collected for

the whole population or for a sample only. It is mostly collected on sample basis. Collection of

data is very difficult job. The enumerator or investigator is the well trained person who collects the

statistical data. The respondents (information) are the persons from whom the information is

collected.

Types of Data:

There are two types (sources) for the collection of data.

(1) Primary Data (2) Secondary Data

(1) Primary Data:

The primary data are the first hand information collected, compiled and published by organization

for some purpose. They are most original data in character and have not undergone any sort of

statistical treatment.

Example: Population census reports are primary data because these are collected, complied and

published by the population census organization.

(2) Secondary Data:

The secondary data are the second hand information which are already collected by some one

(organization) for some purpose and are available for the present study. The secondary data are not

pure in character and have undergone some treatment at least once.

Example: Economics survey of England is secondary data because these are collected by more than

one organization like Bureau of statistics, Board of Revenue, the Banks etc…

Methods of Collecting Primary Data:

Primary data are collected by the following methods:

Personal Investigation: The researcher conducts the survey him/herself and collects data

from it. The data collected in this way is usually accurate and reliable. This method of

collecting data is only applicable in case of small research projects.

Through Investigation: Trained investigators are employed to collect the data. These

investigators contact the individuals and fill in questionnaire after asking the required

information. Most of the organizing implied this method.

Collection through Questionnaire: The researchers get the data from local representation or

agents that are based upon their own experience. This method is quick but gives only rough

estimate.

Through Telephone: The researchers get information through telephone this method is quick

and give accurate information.

Methods of Collecting Secondary Data:

The secondary data are collected by the following sources:

Official: e.g. The publications of the Statistical Division, Ministry of Finance, the Federal

Bureaus of Statistics, Ministries of Food, Agriculture, Industry, Labor etc…

Semi-Official: e.g. State Bank, Railway Board, Central Cotton Committee, Boards of

Economic Enquiry etc…

Publication of Trade Associations, Chambers of Commerce etc…

Technical and Trade Journals and Newspapers.

Research Organizations such as Universities and other institutions.

Difference between Primary and Secondary Data:

The difference between primary and secondary data is only a change of hand. The primary data

are the first hand data information which is directly collected form one source. They are most

original data in character and have not undergone any sort of statistical treatment while the

secondary data are obtained from some other sources or agencies. They are not pure in character and

have undergone some treatment at least once.

For Example: Suppose we interested to find the average age of MS students. We collect the age’s

data by two methods; either by directly collecting from each student himself personally or getting

their ages from the university record. The data collected by the direct personal investigation is called

primary data and the data obtained from the university record is called secondary data.

Classification of Data

The process of arranging data into homogenous group or classes according to some common characteristics

present in the data is called classification.

For Example: The process of sorting letters in a post office, the letters is classified according to the city

further arranged according to streets.

Bases of Classification:

There are four important bases of classification:

(1) Qualitative Base (2) Quantitative Base (3) Geographical Base (4) Chronological or Temporal Base

(1) Qualitative Base:

When the data are classified according to some quality or attributes such as sex, religion, literacy,

intelligence etc…

Example:

Gender

Number of students

Male

1407

Female

538

1945

Total

(2) Quantitative Base:

When the data are classified by quantitative characteristics like heights, weights, ages, income etc…

Example:

Marks

Number of students

0-39

20

40-49

15

60-100

15

(3) Geographical Base:

When the data are classified by geographical regions or location, like states, provinces, cities, countries

etc…

Example:

Region

Central India

West

North

South

Total

Number of companies

50

25

15

10

100

(4) Chronological or Temporal Base:

When the data are classified or arranged by their time of occurrence, such as years, months, weeks, days

etc…

For Example: Time series data.

Region

Central India

West

North

South

Total

Number of companies

50

25

15

10

100

Types of Classification:

(1) One -way Classification:

If we classify observed data keeping in view single characteristic, this type of classification is known as oneway classification.

For Example: The population of world may be classified by religion as Muslim, Christians etc…

(2) Two -way Classification:

If we consider two characteristics at a time in order to classify the observed data then we are doing two way

classifications.

For Example: The population of world may be classified by Religion and Sex.

(3) Multi -way Classification:

We may consider more than two characteristics at a time to classify given data or observed data. In this way

we deal in multi-way classification.

For Example: The population of world may be classified by Religion, Sex and Literacy.

Tabulation of Data

The process of placing classified data into tabular form is known as tabulation. A table is a symmetric

arrangement of statistical data in rows and columns. Rows are horizontal arrangements whereas columns are

vertical arrangements. It may be simple, double or complex depending upon the type of classification.

Types of Tabulation:

(1) Simple Tabulation or One-way Tabulation:

When the data are tabulated to one characteristic, it is said to be simple tabulation or one-way tabulation.

For Example: Tabulation of data on population of world classified by one characteristic like Religion is

example of simple tabulation.

(2) Double Tabulation or Two-way Tabulation:

When the data are tabulated according to two characteristics at a time. It is said to be double tabulation or

two-way tabulation.

For Example: Tabulation of data on population of world classified by two characteristics like Religion and

Sex is example of double tabulation.

(3) Complex Tabulation:

When the data are tabulated according to many characteristics, it is said to be complex tabulation.

For Example: Tabulation of data on population of world classified by two characteristics like Religion, Sex

and Literacy etc…is example of complex tabulation.

Construction of Statistical Table

A statistical table has at least four major parts and some other minor parts.

(1) The Title

(2) The Box Head (column captions)

(3) The Stub (row captions)

(4) The Body

(5) Prefatory Notes

(6) Foots Notes

(7) Source Notes

The general sketch of table indicating its necessary parts is shown below:

----THE TITLE-------Prefatory Notes-------Box Head-------Row Captions----

----Column Captions----

----Stub Entries----

----The Body----

Foot Notes…

Source Notes…

(1) The Title:

A title is the main heading written in capital shown at the top of the table. It must explain the contents of

the tableand throw light on the table as whole different parts of the heading can be separated by commas

there are no full stop be used in the little.

(2) The Box Head (column captions):

The vertical heading and subheading of the column are called columns captions. The spaces were these

column headings are written is called box head. Only the first letter of the box head is in capital letters and

the remaining words must be written in small letters.

(3) The Stub (row captions):

The horizontal headings and sub heading of the row are called row captions and the space where these rows

headings are written is called stub.

(4) The Body:

It is the main part of the table which contains the numerical information classified with respect to row and

column captions.

(5) Prefatory Notes:

A statement given below the title and enclosed in brackets usually describes the units of measurement is

called prefatory notes.

(6) Foot Notes:

It appears immediately below the body of the table providing the further additional explanation.

(7) Source Notes:

The source notes is given at the end of the table indicating the source from when information has been taken.

It includes the information about compiling agency, publication etc…

General Rules of Tabulation:

A table should be simple and attractive. There should be no need of further explanations (details).

Proper and clear headings for columns and rows should be need.

Suitable approximation may be adopted and figures may be rounded off.

The unit of measurement should be well defined.

If the observations are large in number they can be broken into two or three tables.

Thick lines should be used to separate the data under big classes and thin lines to separate the

subclasses of data.

Diagrams and Graphs of Statistical Data

We have discussed the techniques of classification and tabulation that help us in organizing the

collected data in a meaningful fashion. However, this way of presentation of statistical data does not always

prove to be interesting to a layman. Too many figures are often confusing and fail to convey the message

effectively.

One of the most effective and interesting alternative way in which a statistical data may be presented is

through diagrams and graphs. There are several ways in which statistical data may be displayed pictorially

such as different types of graphs and diagrams. The commonly used diagrams and graphs to be discussed in

subsequent paragraphs are given as under:

Types of Diagrams/Charts:

1. Simple Bar Chart

2. Multiple Bar Chart or Cluster Chart

3. Staked Bar Chart or Sub-Divided Bar Chart or Component Bar Chart

Simple Component Bar Chart

Percentage Component Bar Chart

Sub-Divided Rectangular Bar Chart

Pie Chart

Types of Graphs:

1. Histogram

2. Frequency Curve and Polygon

3. Lorenz Curve

Simple Bar Chart

A simple bar chart is used to represents data involving only one variable classified on

spatial, quantitative or temporal basis. In simple bar chart, we make bars of equal width but variable length,

i.e. the magnitude of a quantity is represented by the height or length of the bars. Following steps are

undertaken in drawing a simple bar diagram:

Draw two perpendicular lines one horizontally and the other vertically at an appropriate place of the

paper.

Take the basis of classification along horizontal line (X-axis) and the observed variable along

vertical line (Y-axis) or vice versa.

Marks signs of equal breath for each class and leave equal or not less than half breath in between two

classes.

Finally marks the values of the given variable to prepare required bars.

Example:

Draw simple bar diagram to represent the profits of a bank for 5 years.

Years

Profit (million $)

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

10

12

18

25

42

Simple bar chart showing the profit of a bank for 5 years.

Multiple Bar Chart

By multiple bars diagram two or more sets of inter-related data are represented (multiple bar diagram

facilities comparison between more than one phenomena). The technique of simple bar chart is used to draw

this diagram but the difference is that we use different shades, colors, or dots to distinguish between

different phenomena. We use to draw multiple bar charts if the total of different phenomena is meaningless.

Example:

Draw a multiple bar chart to represent the import and export of Canada (values in $) for the years 1991 to

1995.

Years

Imports

Exports

.

Component Bar Chart or Sub-divided Bar Chart

Sub-divided or component bar chart is used to represent data in which the total magnitude is divided into

different or components.

In this diagram, first we make simple bars for each class taking total magnitude in that class and then divide

these simple bars into parts in the ratio of various components. This type of diagram shows the variation in

different components within each class as well as between different classes. Sub-divided bar diagram is also

known as component bar chart or staked chart.

Example:

The table below shows the quantity in hundred kgs of Wheat, Barley and Oats produced on a certain form

during the years 1991 to 1994.

Years

Wheat

Barley

Oats

Construct a component bar chart to illustrate this data.

Solution:

To make the component bar chart, first of all we have to take year wise total production.

Years

Wheat

Barley

Oats

Total

The required diagram is given below:

Percentage Component Bar Chart

Sub-divided bar chart may be drawn on percentage basis. To draw sub-divided bar chart on percentage basis,

we express each component as the percentage of its respective total. In drawing percentage bar chart, bars of

length equal to 100 for each class are drawn at first step and sub-divided in the proportion of the percentage

of their component in the second step. The diagram so obtained is called percentage component bar chart or

percentage staked bar chart. This type of chart is useful to make comparison in components holding the

difference of total constant.

Example:

The table below shows the quantity in hundred kgs of Wheat, Barley and Oats produced on a certain form

during the years 1991 to 1994.

Wheat

Years

Barley

Oats

Construct a percentage component bar chart to illustrate this data.

Solution:

Necessary computations for the construction of percentage bar chart given below:

Item

Percentage

Wheat

Barley

Oats

Total

Pie Chart

Pie chart can used to compare the relation between the whole and its components. Pie chart is a circular

diagram and the area of the sector of a circle is used in pie chart. Circles are drawn with radii proportional to

the square root of the quantities because the area of a circle is

.

To construct a pie chart (sector diagram), we draw a circle with radius (square root of the total). The total

angle of the circle is

. The angles of each component are calculated by the formula.

Angle of Sector

These angles are made in the circle by mean of a protractor to show different components. The arrangement

of the sectors is usually anti-clock wise.

Example:

The following table gives the details of monthly budget of a family. Represent these figures by a suitable

diagram.

Item of Expenditure

Family Budget

Food

Clothing

House Rent

Fuel and Lighting

Miscellaneous

Total

Solution:

The necessary computations are given below:

Angle of Sector

Items

Expenditure $

Food

Clothing

House Rent

Fuel and Lighting

Miscellaneous

Total

Angle of Sectors

Measures of Central Tendency

According to Prof Bowley "Measures of central tendency (averages) are statistical constants

which enable us to comprehend in a single effort the significance of the whole."

The main objectives of Measure of Central Tendency are

1) To condense data in a single value.

2) To facilitate comparisons between data.

There are different types of averages, each has its own advantages and disadvantages.

Requisites of a Good Measure of Central Tendency:

1. It should be rigidly defined.

2. It should be simple to understand & easy to calculate.

3. It should be based upon all values of given data.

4. It should be capable of further mathematical treatment.

5. It should have sampling stability.

6. It should be not be unduly affected by extreme values

Mean

The mean (or average) of a set of data values is the sum of all of the data values divided by the

number of data values. That is:

Example

The marks of seven students in a mathematics test with a maximum possible mark of 20 are given

below:

15 13 18 16 14 17 12

Find the mean of this set of data values.

Solution:

So, the mean mark is 15.

Symbolically, we can set out the solution as follows:

So, the mean mark is 15.

Arithmetic Mean

This is the most commonly used average which you have also studied and used in lower grades.

Here are two definitions given by two great masters of statistics.

Horace Sacrist : Arithmetic mean is the amount secured by dividing the sum of values of the items

in a series by their number.

W.I. King : The arithmetic average may be defined as the sum of aggregate of a series of items

divided by their number.

Thus, the students should add all observations (values of all items) together and divide this sum by

the number of observations (or items).

Ungrouped Data

Suppose, we have 'n' observations (or measures) x1 , x2 , x3, ......., xn then the Arithmetic mean is

obviously

We shall use the symbol x (pronounced as x bar) to denote the Arithmetic mean. Since we have to

write the sum of observations very frequently, we use the usual symbol ' S ' (pronounced as sigma)

to denote the sum. The symbol xi will be used to denote, in general the 'i' th observation. Then the

sum, x1 + x2 + x3 + .......+ xn will be represented by

or

simply

Therefore the Arithmetic mean of the set x1 + x2 + x3 + .......+ xn is given by,

This method is known as the ''Direct Method".

Example A variable takes the values as given below. Calculate the arithmetic mean of 110, 117,

129, 195, 95, 100, 100, 175, 250 and 750.

Solution: Arithmetic mean =

= 110 + 117 + 129 +195 + 95 +100 +100 +175 +250 + 750 = 2021

and n = 10

Indirect Method (Assumed Mean Method)

A = Assumed Mean =

Calculations:

Let A = 175 then

Sui = -65, -58, -46, +20, -80, -75,-75, +0, + 75, +575

= 670 - 399

= 271/10 = 27.1

\

= 175 + 27.1

= 202.1

Example M.N. Elhance’s earnings for the past week were:

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

$ 450

$ 375

$ 500

$ 350

$ 270

Find his average earning per day.

Solution:

n=5

\ Arithmetic mean =

Therefore, Elhance’s average earning per day is $389

Short-cut Method :

Sometimes the values of x are very big and in that case, to simplify the calculation the short-cut

method is used. For this, first you assume a mean (called as the assumed mean). Let it be A. Now

find the deviations of all the values of x from A. We now get a new variable ui = xi - A

Now find

then

Example The expenditure of ten families in dollars are given below :

Family :

A

B C

D E

F

G

H

I

J

Expenditure : 300 700 100 750 500 80 120 250 100 370

(in dollars).

Calculate the Arithmetic mean.

Solution: Let the assumed mean be $ 500. (as. = assume)

Calculations :

Discrete Series : There is a difference in the methods for finding the arithmetic means of the

individual series and a discrete series. In the discrete series, every term (i.e. value of x) is multiplied

by its corresponding frequency (fixi) and then their total (sum) is found

. The arithmetic

mean is then obtained by dividing the total frequency

by the above sum so

obtained

Therefore, if the observations x1+ x2 + x3 + .......+ xn are repeated f1 + f2+ f3 + ......+ fntimes, then we

have :

Arithmetic mean

The formulae for Arithmetic mean by direct method and by the short-cut methods are as follows:

Direct method

Short-cut method

and u = xi - A

Therefore,

23, 18, 17, 21,

20, 21, 20, 20, 20, 18, 21, 19, 20, 19

Solution: We may tabulate the given observations as follows.

The arithmetic mean is

Example Eight coins were tossed together and the number of times they fell on the side of heads

was observed. The activity was performed 256 times and the frequency obtained for different values

of x, (the number of times it fell on heads) is shown in the following table. Calculate then mean by:

i) Direct method ii) Short-cut method

x:

0

1

2

3

f:

1

9

26 59

4

5

6

7

8

72

52

29

7

1

Solution:

Mean for Grouped data

Continuous series: The procedure of finding the arithmetic mean in this series, is the same as we

have used in the discrete series. The only difference is that in this series, we are given classintervals, whose mid-values (class-marks) are to be calculated first.

Formula, Arithmetic mean

where x = mid-value

Example The weights (in gms) of 30 articles are given below :

14, 16, 16, 14, 22, 13, 15, 24, 23, 14, 20, 17, 21, 18, 18, 19, 20, 17, 16, 15, 11, 22, 21, 20, 17, 18, 19,

22, 23.

Form a grouped frequency table, by dividing the variate range into intervals of equal width, one

class being 11-13 and then compute the arithmetic mean.

Solution:

Example Find the arithmetic mean for the following :

Marks below : 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80

No. of students : 15 35 60 84 96 127 198 250

Solution:

First, we have to convert the cumulative frequencies into frequencies of the respective classes.

Marks Mid- Frequencies U = X -A

values

c.f. f.

A = 45

xi

fiui

0 - 10

5

15

15

- 40

- 600

10 -20

15

35

20

- 30

- 600

20 - 30

25

60

25

- 20

- 500

30 - 40

35

84

24

- 10

- 240

40 - 50 45 ÞA 96

12

0

0

50 - 60

55

127

31

+10

+310

60 - 70

65

198 71

+20

+1420

70 - 80

75

250 52

+30

+1560

Total

MedianProperties Of Arithmetic Mean

1. The sum of the deviations, of all the values of x, from their arithmetic mean, is zero.

Justification :

Since

is a constant,

2. The product of the arithmetic mean and the number of items gives the total of all items.

Justification :

or

3. If

and

are the arithmetic mean of two samples of sizes n1 and n2 respectively then, the

arithmetic mean of the distribution combining the two can be calculated as

This formula can be extended for still more groups or samples.

Justification :

Similarly

= total of the observations of the first sample

= total of the observations of the first sample

The combined mean of the two samples

=

=

Merits

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

It is rigidly defined. Its value is always definite.

It is easy to calculate and easy to understand. Hence it is very popular.

It is based on all the observations; so that it becomes a good representative.

It can be easily used for comparison.

It is capable of further algebraic treatment such as finding the sum of the values of the

observations, if the mean and the total number of the observations are given; finding the

combined arithmetic mean when different groups are given etc.

6. It is not affected much by sampling fluctuations.

Demerits

1. It is affected by outliers or extreme values. For example, the average (A.) mean of 10, 15, 25

and 500 is

Now observe first three values whose A.mean is

Due to the outlier 500 the A. mean of the four numbers is raised to 137.5. In such a case A.

mean is not a good representative of the given data.

2.

3.

4.

5.

It is a value which may not be present in the given data.

Many a times it gives absurd results like 4.4 children per family.

It is not possible to take out the averages of ratios and percentages.

We cannot calculate it when open-end class intervals are present in the data.

Median

It is the value of the size of the central item of the arranged data (data arranged in the ascending or

the descending order). Thus, it is the value of the middle item and divides the series in to equal

parts.

In Connor’s words - "The median is that value of the variable which divides the group into two

equal parts, one part comprising all values greater and the other all values lesser than the median."

For example, the daily wages of 7 workers are 5, 7, 9, 11, 12, 14 and 15 dollars. This series contains

7 terms. The fourth term i.e. $11 is the median.

Median In Individual Series (ungrouped Data)

1. Set the individual series either in the ascending (increasing) or in the descending

(decreasing) order, of the size of its items or observations.

2. If the total number of observations be 'n' then

A. If 'n' is odd,

The median = size of

B. If 'n' is even, the median

observation

=

Example The following figures represent the number of books issued at the counter of a Statistics

library on 11 different days. 96, 180, 98, 75, 270, 80, 102, 100, 94, 75 and 200. Calculate the

median.

Solution:

Arrange the data in the ascending order as 75, 75, 80, 94, 96, 98, 100, 102,180, 200, 270.

Now the total number of items 'n'= 11 (odd)

Therefore, the median = size of

item

= size of

item

= size of 5th item

= 98 books per day

Example The population (in thousands) of 36 metropolitan cities are as follows :

2468, 591, 437, 20, 213, 143, 1490, 407, 284, 176, 263, 19, 181, 777, 387, 302, 213, 204, 153, 733,

391, 176 178, 122, 532, 360, 65, 260, 193, 92, 672, 258, 239, 160, 147, 151. Calculate the median.

Solution:

Arranging the terms in the ascending order as :

20, 65, 92, 131, 142, 143, 147, 151, 153, 160, 169, 176, 178, 181, 193, 204, (213, 39), 258, 263,

260, 384, 302, 360, 387, 391, 407, 437, 522, 591, 672, 733, 777, 1490, 2488.

Since total number of items n = 36 (Even).

the median

=

Median In Discrete Series

Steps :

1. Arrange the data in ascending or descending order of magnitude.

2. Find the cumulative frequencies.

3. Apply the formula :

A. If 'n' =

(odd) then,

Median = size of

B. If 'n' =

item

(even) then,

Median =

ExampleLocate the median in the following distribution.

Size

: 8 10

Frequency : 7

7

12 14

12

28

16

10

18

20

9

6

Solution:

Therefore, the median =

=

= size of 38th item

In the order of the cumulative frequency, the 38th term is present in the 50th cumulative frequency,

whose size is 14.

Therefore, the median = 14

Median In Continuous Series (grouped Data)

Steps :

1. Determine the particular class in which the value of the median lies. Use

the median and not

as the rank of

2. After ascertaining the class in which median lies, the following formula is used for

determining the exact value of the median.

Median =

where, = lower limit of the median class, the class in which the middle item of the

distribution lies.

= upper limit of the median class

c.f = cumulative frequency of the class preceding the median class

f = sample frequency of the median class

It should be noted that while interpolating the median value of frequency distribution it is

assumed that the variable is continuous and that there is an orderly and even distribution of

items within each class

Example Calculate the median for the following and verify it graphically.

Age (years) : 20-25

No. of person :

Solution:

70

25-30

80

30-35

180

35-40 40-45

150

20

Therefore, Median

Median =

Here

= 30,

= 35,

= 250, c.f. = 150 and f = 180

Therefore, Median

Merits Of Median

1. It is rigidly defined.

2. It is easy to calculate and understand.

3. It is not affected by extreme values like the arithmetic mean. For example, 5 persons have

their incomes $2000, $2500, $2600, $3000, $5000. The median would be $2600 while the

arithmetic mean would be $3020.

4. It can be found by mere inspection.

5. It is fully representative and can be computed easily.

6. It can be used for qualitative studies.

7. Even if the extreme values are unknown, median can be calculated if one knows the number

of items.

8. It can be obtained graphically.

Demerits Of Median

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

It may not be representative if the distribution is irregular and abnormal.

It is not capable of further algebraic treatment.

It is not based on all observations.

It is affected by sample fluctuations.

The arrangement of the data in the order of magnitude is absolutely necessary.

Demerits Of Median

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

It may not be representative if the distribution is irregular and abnormal.

It is not capable of further algebraic treatment.

It is not based on all observations.

It is affected by sample fluctuations.

The arrangement of the data in the order of magnitude is absolutely necessary.

Mode

It is the size of that item which possesses the maximum frequency. According to Professor Kenney

and Keeping, the value of the variable which occurs most frequently in a distribution is called the

mode.

It is the most common value. It is the point of maximum density.

Ungrouped Data

Individual series : The mode of this series can be obtained by mere inspection. The number which

occurs most often is the mode.

Example Locate mode in the data 7, 12, 8, 5, 9, 6, 10, 9, 4, 9, 9

Solution : On inspection, it is observed that the number 9 has maximum frequency. Therefore 9 is

the mode.

Note that if in any series, two or more numbers have the maximum frequency, then the mode will be

difficult to calculate. Such series are called as Bi-modal, Tri-modal or Multi-modal series.

Grouped Data

Steps :

1. Determine the modal class which as the maximum frequency.

2. By interpolation the value of the mode can be calculated as -

Mode =

where

Example Calculate the modal wages.

Daily wages in $ : 20 -25 25-30 30-35 35-40 40-45 45-50

No. of workers :

1

3

8

12

7

5

Verify it graphically.

Solution:

Here the maximum frequency is 12, corresponding to the class interval (35 - 40) which is the modal

class.

Therefore

By interpolation

Mode =

Modal wages is $37.22

MERITS OF MODE

1. It is simple to calculate.

2. In individual or discrete distribution it can be located by mere inspection.

3. It is easy to understand. Everyone is used to the idea of average size of a garment, an

average American etc.

4. It is not isolated like the median as it is the most common item.

5. Like the Average mean, it is not a value which cannot be found in the series.

6. It is not necessary to know all the items. What we need the point of maximum density

frequency.

7. It is not affected by sampling fluctuations.

DEMERITS

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

It is ill defined.

It is not based on all observations.

It is not capable of further algebraic treatment.

It is not a good representative of the data

Sometimes there are more than one values of mode.

IMPOTANT QUESTIONS:1. What is secondary data. What are the sources of secondary data?

2.What are the advantages of a diagrammatic representation?

3.Explain any three methods of collecting primary data. Give their merits and

demerits

4. From the following table, draw Ogive curves and hence find median

Wages : 0-10 10-20 20-30 30-40 40-50 50-60 60-70

No. of workers: 5 8 10 14 11 6 3

5. Calculate the mean median and mode for the following data

Life in hours : 0-400 400-800

No of Bulbs:

4

800-1200

12

6.Write a note on graphical representation?

40

1200-1600

41

UNIT II

CONTENTS

1. Measures of Dispersion

2. Range

3. Quartile Deviation

4. Mean Deviation

5. Standard Deviation and Co-efficient of Variation.

6. Skewness – Meaning

7. Measures of Skewness

8. Pearson’s and Bowle’s co-efficient of Skewness.

MEASURES OF DISPERSION

INTRODUCTION

Dispersion also known as scatter, spread or variation measures the extent to which the items vary

from some central value. Since measures of dispersion give an average of the differences of

various items from an average, they are also called averages of the second order.

SIGNIFICANCE OF MEASURING DISPERSION

Measures of variation are needed for four basic purposes:

1)

To determine the reliability of an average.

2) To serve as a basis for the control of the variability.

3) To compare two or more series with regard to their variability.

PROPERTIES OF A GOOD MEASURE OF VARIATION

• It should be simple to understand.

• It should be easy to compute.

• It should be rigidly defined.

• It should be based on each and every item of the distribution.

• It should be amenable to further algebraic treatment.

• It should have sampling stability.

• It should not be unduly affected by extreme items.

METHODS OF VARIATION

I. The Range

II. The Interquartile and Quartile Deviation

III. The Mean Deviation or Average Deviation

IV. The Standard Deviation

I. RANGE

It is defined as the difference between the value of the smallest item and the value of the largest

item included in the distribution.

Range = L - S

Coefficient of Range = L - S

L+S

Note: a measure of dispersion is the ratio of a measure of absolute to an appropriate average.

USES OF RANGE

•

Quality Control

The idea basically is that if the range - the difference between the largest and smallest mass

produced items - increases beyond a certain point, the production machinery should be

examined to find out why the items produced have not followed their usual more

consistent pattern.

•

Fluctuations in the share prices

Range is useful in studying the variations in the prices of stocks and shares and other

commodities that are sensitive to price changes from one period to another.

•

Weather forecasts

The meteorological department does make use of the range in determining the difference

between the minimum temperature and the maximum temperature.

INTERQUARTILE RANGE AND QUARTILE DEVIATIONIt represents the difference

between the third quartile and the first quartile.

Interquartile Range= Q3 - Q1

Quartile Deviation or Q.D. = Q3 - Q1

Coefficient of Q.D. = (Q3 - Q1)/2 = Q3 - Q1

Example: Find the median, lower quartile, upper quartile and inter-quartile range of the following

data set of scores: 19, 22, 24, 20, 24, 27, 25, 24, 30?

Solution:

First, lets arrange of the values in an ascending order:

19, 20, 22, 24, 24, 24, 25, 27, 30

Now lets calculate the Median,

Median = (n+12)th term

= (9+12)th term

= 5thterm

= 24

Lower quartile = (n+14)th term

= (9+14)th term

= (104)th term

= 2.5th

Find the average of 2nd and 3rd term

= 20+222

= 422

= 21

Upper quartile = (3(n+1)4)th

= (3(9+1)4)th

= (3(10)4)th

= (304)th

= 7.5th

(lets find the average of 7th and 8th term)

= 25+272

= 522

= 26

Inter - quartile= Upper quartile - lower quartile

= 26 - 21

=5

Example: Find the first quartile, second quartile and third quartile of the given information of the

following sequence 4, 77, 16, 59, 93, 88?

Solution:

First, lets arrange of the values in an ascending order:

4, 16, 59, 77, 88, 93

Given n = 6

∴ Lower quartile = (n+14)th term

= (6+14)th term

= (74)th term

= 1.7th term

Here we can consider the 2nd term (rounding 1.7 to nearest whole integer) from the set of

observation.

⇒ 2nd term = 16

Lower quartile = 16

Upper quartile = (3(n+1)4)th term

= (3(6+1)4)th term

= (214)th term

= 5.25th

Here we can consider the 5thterm (rounding 5.25 to nearest whole integer) from the set of

observation.

⇒ 5.25th = 88

Upper quartile= 88

Inter-quartile= Upper quartile - lower quartile

= 88 - 16

= 72

MEAN DEVIATION

The mean deviation is also known as the average deviation. It is the average difference between

the items in a distribution and the median or mean of that series.

Computation of Mean Deviation - Individuals Observations

•

A practical way around this problem is simply to ignore the fact that some deviations are

negative while others are positive by averaging the absolute values of the deviations.

•

This measure (called the mean deviation) tells us the average (mean) amount that the

values for all cases deviate (regardless of whether they are higher or lower) from the

average (mean) value.

Indeed, the Mean Deviation is an intuitive, understand-able, and perfectly reasonable measure of

dispersion, and it is occasionally used in research

THE MEAN DEVIATION

The mean deviation (average deviation), of a set of N numbers X1 ,X2, X3, X4, X5,……, XN is

defined by

N

Xj X

X X = X X , where X is the arithmetic mean

j 1

Mean deviation (MD) =

=

N

N

of the numbers and X X is the absolute value of the deviation of X

Example:

Find the mean deviation of the set

3, 4, 6, 8, 9.

Solution:

Arithmetic mean =

3 4 6 8 9 30

6

5

5

36 46 66 86 96

The mean deviation ( X ) =

3 2 0 2 3

5

=

5

3 2 0 2 3 10

5

5

2

THE MEAN DEVIATION OF A GROUPED DATA

For the data

Values

X1 X2 X3 …… XN

Frequencies f1

f2

f3

….

Fm

=

j

from X .

The mean deviation can be computed as

m

fj Xj X

f XX

j 1

Mean deviation =

XX

N

N

STANDARD DEVIATION

The standard deviation is calculated as follows:

Steps to calculate Standard deviation :

1. Calculate the mean (average or

) for the data set.

2. Determine the deviation from the mean (

) for each value

by subtracting the

mean from the value. A negative deviation means that observation fell below the mean. A

positive deviation indicates that the observation fell above the mean.

3. Calculate the square of the deviation

for each observation calculated in step 2.

This will always be a positive number (a negative value times a negative value equals a

positive value).

4. Add up the squares calculated in step 3:

5. Subtract 1 from the number of observations:

-1

6. Divide the total from step #4 by the result of step 5:

7. Calculate the square root of the value calculated in step 6:

8. The result is the standard deviation

Example: During a survey, 6 students were asked that how many hours per day they study on an

average? Their answers were as follows: 2, 6, 5, 3, 4, 1. Evaluate the standard deviation.

Solution:

Formula for mean is given by:

x¯ = ∑x−in

x¯ = 2+6+5+3+4+16

= 3.5

Construct the following table for standard deviation:

xi

2

6

5

3

4

1

xi−x¯ (xi−x¯)2

-1.5 2.25

2.5 6.25

1.5 2.25

-0.5 0.25

0.5 0.25

-2.5 6.25

∑(x−i−x¯)2 = 17.5

Formula for standard deviation is given by:

S = ∑ni=1(xi−x¯)2n−−−−−−−−−√

S=17.56−−−√

S = 2.92−−−−√ = 1.71

Example: Marks obtained by 4 students in a class are 25, 15, 20, 18. Find the standard deviation of

the sample?

Solution:

Formula for mean is given by:

x¯ = ∑ni=1xin

x¯ = 25+15+20+184

= 19.5

Construct the following table for standard deviation:

xi xi−x¯

25 5.5

15 -4.5

20 0.5

18 -1.5

(xi−x¯)2

30.25

20.25

0.25

2.25

∑(xi−x¯)2 = 53

Formula for standard deviation is given by:

S = ∑ni=1(xi−x¯)2n−1−−−−−−−−−√

S=533−−√

S = 4.2

SKEWNESS

The first thing you usually notice about a distribution’s shape is whether it has one mode (peak) or

more than one. If it’s unimodal (has just one peak), like most data sets, the next thing you notice is

whether it’s symmetric or skewed to one side. If the bulk of the data is at the left and the right tail

is longer, we say that the distribution is skewed right or positively skewed; if the peak is toward

the right and the left tail is longer, we say that the distribution is skewed left or negatively skewed.

Look at the two graphs below. They both have μ = 0.6923 and σ = 0.1685, but their shapes are

different.

Beta(α=4.5, β=2)

skewness = −0.5370

1.3846 − Beta(α=4.5, β=2)

skewness = +0.5370

The first one is moderately skewed left: the left tail is longer and most of the distribution is at the

right. By contrast, the second distribution is moderately skewed right: its right tail is longer and

most of the distribution is at the left.

You can get a general impression of skewness by drawing a histogram (MATH200A part 1), but

there are also some common numerical measures of skewness. Some authors favor one, some favor

another. This Web page presents one of them. In fact, these are the same formulas that Excel uses in

its “Descriptive Statistics” tool in Analysis Toolpak.

You may remember that the mean and standard deviation have the same units as the original

data, and the variance has the square of those units. However, the skewness has no units: it’s a pure

number, like a z-score.

The moment coefficient of skewness of a data set is

skewness: g1 = m3 / m23/2

(1)where

m3 = ∑(x−x̅)3 / n and m2 = ∑(x−x̅)2 / n

x̅ is the mean and n is the sample size, as usual. m3 is called the third moment of the data set. m2 is

the variance, the square of the standard deviation.

You’ll remember that you have to choose one of two different measures of standard deviation,

depending on whether you have data for the whole population or just a sample. The same is true of

skewness. If you have the whole population, then g1 above is the measure of skewness. But if you

have just a sample, you need the sample skewness:

(2)sample skewness:

source: D. N. Joanes and C. A. Gill. “Comparing Measures of Sample Skewness and Kurtosis”.The

Statistician 47(1):183–189.

Excel doesn’t concern itself with whether you have a sample or a population: its measure of

skewness is always G1.

Example 1:

Height

(inches)

Class

Mark, x

Frequency, f

59.5–62.5

61

5

62.5–65.5

64

18

65.5–68.5

67

42

68.5–71.5

70

27

71.5–74.5

73

8

Here are grouped data for heights of 100 randomly selected male students, adapted from Spiegel &

Stephens,Theory and Problems of Statistics 3/e (McGraw-Hill, 1999), page 68.

A histogram shows that the data are skewed left, not symmetric.

But how highly skewed are they, compared to other data sets? To answer this question, you have to

compute the skewness.

Begin with the sample size and sample mean. (The sample size was given, but it never hurts to

check.)

n = 5+18+42+27+8 = 100

x̅ = (61×5 + 64×18 + 67×42 + 70×27 + 73×8) ÷ 100

x̅ = 9305 + 1152 + 2814 + 1890 + 584) ÷ 100

x̅ = 6745÷100 = 67.45

Now, with the mean in hand, you can compute the skewness. (Of course in real life you’d probably

use Excel or a statistics package, but it’s good to know where the numbers come from.)

xf

(x−x̅) (x−x̅)²f

5

305

-6.45

208.01

-1341.68

64

18

1152

-3.45

214.25

-739.15

67

42

2814

-0.45

8.51

-3.83

70

27

1890

2.55

175.57

447.70

73

8

584

5.55

246.42

1367.63

∑

6745

n/a

852.75

−269.33

x̅, m2, m3

67.45

n/a

8.5275

−2.6933

Class Mark, x

Frequency, f

61

(x−x̅)³f

Finally, the skewness is

g1 = m3 / m23/2 = −2.6933 / 8.52753/2 = −0.1082

But wait, there’s more! That would be the skewness if the you had data for the whole population.

But obviously there are more than 100 male students in the world, or even in almost any school, so

what you have here is a sample, not the population. You must compute the sample skewness:

= [√(100×99) / 98] [−2.6933 / 8.52753/2] = −0.1098

IMPOTANT QUESTIONS

1.Marks obtained by 4 students in a class are25,15,20,18.Findthestandard deviation of the

sample?

2. Find the mean deviation of the set

3, 4, 6, 8, 9.

3. Explain the skewness with example

4. Discuss the Range and Quartile Deviation

UNIT-III

CONTENTS

1. Correlation –Meaning and Definition

2. Scatter diagram

3. Karl Pearson’s co-efficient of Correlation

4. Rank Correlation

5. Co-efficient of Concurrent deviation

6. Regression Analysis

7. Meaning of regression and linear prediction

8. Regression in two variables

Correlation –Meaning and Definition

Correlation measures the degree of linear relation between the variables. The existence of

correlation between variables does not necessarily mean that one is the cause of the

change in the other. It should noted that the correlation analysis merely helps in

determining the degree of association between two variables, but it does not tell any

thing about the cause and effect relationship. While interpreting the correlation

coefficient, it is necessary to see whether there is any cause and effect relationship

between variables under study. If there is no such relationship, the observed is

meaningless.

In correlation analysis, all variables are assumed to be random variables.

Types of Correlation

There are two important types of correlation. They are (1) Positive

and Negative correlation and (2) Linear and Non – Linear correlation.

Positive and Negative Correlation

If the values of the two variables deviate in the same direction i.e. if

an increase (or decrease) in the values of one variable results, on an average,

in a corresponding increase (or decrease) in the values of the other variable

the correlation is said to be positive.

Some examples of series of positive correlation are:

(i) Heights and weights;

(ii) Household income and expenditure;

(iii) Price and supply of commodities;

(iv) Amount of rainfall and yield of crops.

Correlation between two variables is said to be negative or inverse if

the variables deviate in opposite direction. That is, if the increase in the

variables deviate in opposite direction. That is, if increase (or decrease) in

the values of one variable results on an average, in corresponding decrease

(or increase) in the values of other variable.

Some examples of series of negative correlation are:

(i) Volume and pressure of perfect gas;

(ii) Current and resistance [keeping the voltage constant] (iii) Price and demand of goods.

Note:

(i) If the points are very close to each other, a fairly good amount of

correlation can be expected between the two variables. On the

other hand if they are widely scattered a poor correlation can be

expected between them.

(ii) If the points are scattered and they reveal no upward or downward

trend as in the case of (d) then we say the variables are

uncorrelated.

(iii) If there is an upward trend rising from the lower left hand corner

and going upward to the upper right hand corner, the correlation

obtained from the graph is said to be positive. Also, if there is a

downward trend from the upper left hand corner the correlation

obtained is said to be negative.

The Scatter Diagram

DEFINITION

In a scatter diagram, the relation between two numerical variables is presented graphically. One

variable (the independent variable X) defines the horizontal axis and the other (dependent

variable Y) defines the vertical axis. The values of the two variables on the same row in the data

spreadsheet, give the points in the diagram.

Steps to draw the scatter diagram :

Scatter diagram is a graphic picture of the sample data. Suppose a random sample of n

pairs of observations has the values

. These

points are plotted on a rectangular co-ordinate system taking independent variable on Xaxis and the dependent variable on Y-axis. Whatever be the name of the independent

variable, it is to be taken on X-axis. Suppose the plotted points are as shown in figure (a).

Such a diagram is called scatter diagram. In this figure, we see that when X has a small

value, Y is also small and when X takes a large value, Y also takes a large value. This is

called direct or positive

relationshipbetween X and Y. The plotted points cluster around a straight line. It appears

that if a straight line is drawn passing through the points, the line will be a good

approximation for representing the original data. Suppose we draw a line AB to represent

the scattered points. The line AB rises from left to theright and has positive slope. This line

can be used to establish an

IMPORTANT QUESTIONS

1.Explain The Scatter Diagram

2.Disscus the correlation

3.Write a note on Positive and Negative Correlation

UNIT –IV

CONTENTS

1. Time Series – Meaning

2. Components and Models

3. Business forecasting

4. Methods of estimating trend

5. Graphic, Semi-average, Moving average and

6. Method of Least squares

7. Seasonal Variation

8. Method of Simple average

9. Index Numbers – Meaning

10. Uses and Methods of construction

11. Un-weighted and Weighted index numbers –

12. Tests of an Index number

13. Cost of living index number

INDEX NUMBERS

Definitions

An index number is a percentage ratio of prices, quantities or values comparing two time periods or

two points in time. The time period that serves as a basis for the comparison is called the base

period and the period that is compared to the base period is called the given or current period.

A price index measures the change in the money value of an item (or group of items) over time

whereas a quantity index measures the non-monetary value of an item (or a group of items) over

time.

An index number that represents a percentage comparison of the number of cars sold in a given

month as compared with that of a base month is a quantity index. A price index represents a

comparison of prices between two time periods and, finally, a value index is one that represents a

comparison of the total value of production or sales in two time periods without regard to whether

the observed difference is a result of differences in quantity, price or both.

Index numbers are also differentiated according to the number of commodities or products included

in the comparison. A simple index, also known as a relative, is a comparison involving only one

item but an index whose calculation is based on several items is known as an aggregate or

composite index. A very famous example of a composite index is the Retail Prices Index (RPI),

which measures the changes in costs in the items of expenditure of the average household.

Index points

The term 'points' refers to the difference between the index values in two time periods. If the indices

for 1999 and 2000 for a certain item are 137 and 151 respectively, it would mean that there has

been an increase

of(m-137) x 100 = ,0.2%.

137

The base period

The base period, which is the starting point for all comparison, always has an index of 100.

Notation

All indices pertaining to the base period have an 'o' (old) as subscript and all those involving the

given period have an 'n' (new) as subscript.

FORMULAE

Simple price index

p

Ip = —!L x 100

po

q

Iq = — x 100

q

oTime series of relatives

Given the values of some commodity over time (time series), there are two ways of computing

index relatives:

Simple quantity index

3) The fixed base method

A base year is selected and all subsequent changes are measured against this base. We use

such an approach only if the basic nature of the commodity is unchanged over time.

4) The chain base method

In this case, changes are calculated with respect to the value of the commodity in the period

immediately before. This approach is used for any set of commodity values but is necessarily used

if the basic nature of the commodity is changing over time.

Rebasing

It is often necessary to update the base period of an index because it is too far in the past. This is

done by assigning a value of 100 to the new base. All necessary adjustments should be made

accordingly thereafter. If a base period is kept for too long, the subsequent indices do tend to have

huge values.

The following table shows that the base year 1990 is outdated since the index for 2001 has almost

reached

400. If we choose 1997 as the new base, then we should multiply all the indices by 100 :

240.4

Year

1990

Index

100.0

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

112.3

124.5

137.8

145.2

178.0

200.3

240.4

281.9

322.2

357.1

389.5

Rebased

index

41.6

46.7

51.8

57.3

60.4

74.0

83.3

100.0

117.3

134.0

148.5

162.0

Rebasing is also used in order to enable comparison between sets of indices. If they have different

base periods, one of them will have to be rebased so as to facilitate the comparison between their

rates of increase or decrease.

Time series deflation

The real value of a commodity can be measured in terms of an indicator such as the rate of

inflation (normally represented by the Retail Prices Index). For example, if the price of a

commodity were $10 in 1998 and $11 in 1999, we would deduce that there has been an increase of

10% but if we are told that, during that period, the prices in general increased by 12%, then we

would argue that the real cost of the commodity has decreased.

Example (deflation)

Year

Wages($)

RPI

Real wages($)

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

12 000

250

260

275

295

315

12 000

12 019

11 818

11 441

11 111

•

5

00

•

0

00

III.

5

00

IV.

00

0

Real wages index

100.

0

100.

2

98.5

95.3

92.6

base indicatorReal wage = Wage x

current indicator

We observe that though the wages have been increasing regularly by $500 every year, the real

wages have been decreasing during 1992-94 with respect to the RPI. This shows that the

increase has not been able to match the rise in standard of living during those years.

Composite (aggregate) index numbers

The RPI, which considers components such as food, alcoholic drink, tobacco and housing, is an

example of a composite index.

FORMULA

I (simple

Simple aggregate price index

Z pn

aggregate) = — ---------------x 100

Zp.

Drawbacks

❖

❖

It ignores the quantities of each item consumed

It ignores the units to which the price refers

Average relatives indices

To overcome the problem of different units, we consider the changes in prices as ratios rather

than absolutes so that all price movements are treated as equally important.

FORMULA

1p

Average price relatives index = — Z—- x 100 where k is the number of goods.

Weighted means of relatives indices

In the above discussion, the relative importance of each item has not been taken into

consideration. Bread is probably more important than soft drinks. To compensate for this, we

attach a weight to each item so as to reflect its importance. Weightings are assigned to each item

as a result of market research to decide about their relative importance. For a simple cost of

living index, it would be necessary to find out how much the average person or household

spends each week on each item to determine their respective weightings.

The method of weightings involves

1.

2.

Calculating index relatives for each of the components

Using the weights given to obtain a weighted average of the relatives

FORMULA

Z wI

Weighted means of relatives index = —-— where w is the weighting factor and I is the index

relative.

Zw

Laspeyre and Paasche indices

The Laspeyre indices use weights from the base period and are therefore sometimes called baseweighted indices whereas the Paasche indices use current time period weights.

FORMULAE

Laspeyre price index

Z Pnq

° x 100

Z poqo

Laspeyre quantity index Z InPo x 100

Z qopo

Paasche price index

Z

^ n ^ n x 100

Z

poq

n

Zq

Paasche quantity index

p

n

—- x 100

Z qopn

Comparison between Laspeyre and Paasche indices

LASPEYRE INDICES

It requires quantities to be ascertained for base year only.

The denominator is fixed so that the index may be calculated as soon as the

current prices or quantities are known.

3.

Laspeyre index numbers can be directly compared for several time periods

because the denominator is fixed.

4.

The weights of a Laspeyre become out of date.

5.

It assumes that, whatever the price changes, the quantities purchased will remain

the same. It therefore assumes that, as goods become more expensive, the same

quantities will be purchased. Inflation could therefore be overstated.

1.

2.

PAASCHE INDICES

It requires quantities to be ascertained every time period and this may prove to be

very costly.

2.

The denominator has to be recalculated every time period. The index cannot be

calculated until the end of the period when the current prices and quantities are known.

3.

Comparisons can only be drawn directly between the current year and the base

year because the denominator has to be recalculated every year.

4.

Paasche indices are updated every year.

5.

The effect of current weighting means that greater importance is placed on goods

that are relative cheaper now than what they were in the base year. Inflation could

therefore be understated.

1.

Construction of an index

After the purpose of the index has been specified, we must make sure that the items

selected from the universe of commodities must be fully representative. These items must be

very well defined and their values must be easily verifiable.

The choice of items for the Retail Prices Index (RPI), for example, is not very easy,

especially that we cannot choose all domestic items. Thus, a selective basket of goods must be

found, including spending on mortgages and rents, public transport, food and drink, electricity,

gas, telephone, clothing, leisure activities and so on.

Data must therefore be collected to determine the values of the items and the weights to

be assigned to them. For a price index, an actual average of the actual prices must be calculated

since prices keep fluctuating from place to place and from time to time. It is common practice to

use quantities as weights when calculating a price index and use prices as weights when

calculating a quantity index. Other difficulties may arise when calculating a cost of living index for example, it might not be that easy to define a typical family.

The choice of a base year is made quite easily while taking care that the year is

representative and that it was not a period in which prices and quantities had extreme values. A

base year should be regularly updated in order to reflect patterns of consumption very clearly. In

so doing, we prevent actual index numbers from becoming too large, especially when a base

year is outdated.

Limitations of index numbers

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Weightings may become outdated.

A change in the items may occur.

The data used to calculate index numbers might be incomplete, outdated or inaccurate.

No base year is perfectly representative of some particular period of time.

The basket of goods is often selective.

A national index may not be relevant at the rural or urban levels.

An index may exclude important items.

Misinterpretations of index numbers

1.

2.

Rise in prices should be interpreted with respect to the immediately previous time period.

A fall in rate of inflation does not imply a fall in prices.

IMPORTANT QUASTION

1. Explain the use of index numbers

2. Explain Components and Models

3. Explain Business forecasting

4. Explain Methods of estimating trend

5. Explain Graphic, Semi-average, Moving average and

6. Explain Method of Least squares

7. Explain Seasonal Variation

8. Explain Method of Simple average

9. Explain Index Numbers – Meaning

10. Explain Uses and Methods of construction

11. Explain Un-weighted and Weighted index numbers –

12. Explain Tests of an Index number

13. Explain Cost of living index number

UNIT-V

CONTENTS

1.Probability Concept and Definition

2.Addition and Multiplication theorems of Probability

3.simple problems

PROBABILITY

1) Sample Space and Events

Terminology

a) A Probability experiment

When you toss a coin or pick a card from a deck of playing cards or roll a dice, the act

constitutes a probability experiment. In a probability experiment, the chances are well defined

with equal chances of occurrence e.g. there are only two possible chances of occurrence in

tossing a coin. You either get a head or tail. The head and the tail have equal chances of

occurrence.

b) An Outcome

This is defined as the result of a single trial of a probability experiment e.g. When you toss a

coin once, you either get head or tail.

c). A trial

This refers to an activity of carrying out an experiment like picking a card from a deck of cards

or rolling a die or dices.

d). Sample Space

This refers to all possible outcomes of a probability experiment. e.g. in tossing a coin, the

outcomes are either Head(H) or tail(T) i.e there are only two possible outcomes in tossing a

coin. The chances of obtaining a head or a tail are equal.

e). A Simple and Compound Events

In an experimental probability, an event with only one outcome is called a simple event. If an

event has two or more outcomes, it is called a compound event.

2) Definition of Probability.

Probability can be defined as the mathematics of chance. There are mainly four approaches to

probability;

1)

2)

3)

4)

The classical or priori approach

The relative frequency or empirical approach

The axiomatic approach

The personalistic approach

The Classical or Priori Approach

Probability is the ratio of the number of favourable cases as compared to the total likely cases.

Suppose an event can occur in N ways out of a total of M possible ways. Then the probability of

occurrence of the event is denoted by

p=Pr(N)=

N

. Probability refers to the ratio of possible outcomes to all possible outcomes.

M

The probability of non-occurrence of the same event is given by {1-p(occurrence)}. The

probability of occurrence plus non-occurrence is equal to one.

If probability occurrence; p(O) and probability of non-occurrence (O’), then p(O)+p(O’)=1.

Empirical Probability ( Relative Frequency Probability)

Empirical probability arises when frequency distributions are used.

For example:

Observation ( X)

0

1

2

3

4

Frequency ( f)

3

7

10

16

11

The probability of observation (X) occurring 2 times is given by the formulae

P(2)=

freuency of 2

f (2)

10

10

sum of frequencies f 3 7 10 16 11 47

3) Properties of Probability

a) Probability of any event lies between 0 and 1 i.e. 0 p(O) 1. It follows that

probability

cannot be negative nor greater than 1.

b) Probability of an impossible event ( an event that cannot occur ) is always zero(0)

c) Probability of an event that will certainly occur is 1.

d) The total sum of probabilities of all the possible outcomes in a sample space is

always

equal to one(1).

e) If the probability of occurrence is p(o)= A, then the probability of non-occurrence

is 1-A.

RULES OF PROBABILITY

ADDITION RULES

1) Rule 1: When two events A and B are mutually exclusive, then

P(A or B)=P(A)+P(B)

Example: When a is tossed, find the probability of getting a 3 or 5.

Solution: P(3) =1/6 and P(5) =1/6.

Therefore P( 3 or 5) = P(3) + P(5) = 1/6+1/6 =2/6=1/3.

2) Rule 2: If A and B are two events that are NOT mutually exclusive, then

P(A or B) = P(A) + P(B) - P(A and B), where A and B means the number of outcomes

that event A and B have in common.

Example: When a card is drawn from a pack of 52 cards, find the probability that the card is a

10 or a heart.

Solution:

P( 10) = 4/52 and P( heart)=13/52

P ( 10 that is Heart) = 1/52

P( A or B) = P(A) +P(B)-P( A and B) = 4/52 _ 13/52 – 1/52 = 16/52.

MULTIPLICATION RULES

1) Rule 1: For two independent events A and B, then P( A and B) = P(A) x P(B).

Example: Determine the probability of obtaining a 5 on a die and a tail on a coin in one

throw.

Solution: P( 5) =1/6 and P(T) =1/2.

P(5 and T)= P( 5) x P(T) = 1/6 x ½= 1/12.

2) Rule 2: When to events are dependent, the probability of both events occurring is P(A and

B)=P(A) x P(B|A), where P(B|A) is the probability that event B occurs given that event A has

already occurred.

Example: Find the probability of obtaining two Aces from a pack of 52 cards without

replacement.

Solution: P( Ace) =2/52 and P( second Ace if NO replacement) = 3/51

Therefore P(Ace and Ace) = P(Ace) x P( Second Ace) = 4/52 x 3/51 = 1/221

Important Questions

1.Explain Probability

2. Write the Addition theorems of Probability

3. Write the Multiplication theorems of Probability

4. Find the probability of obtaining two Aces from a pack of 52 cards without replacement.

5. When a is tossed, find the probability of getting a 3 or 5.