CHAPTER I

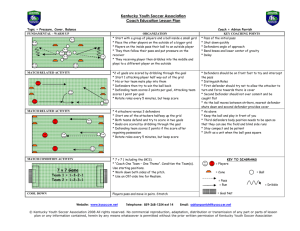

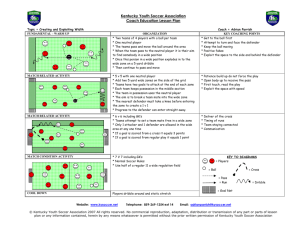

advertisement