الشريحة 1

advertisement

Dr. Mohanad Abu Sabha

Course Title: Linguistics 1

Course Number: Eng 320

Credit Hours:3

Title: The Study of Language

Author: George Yule

And Edition:1985,Gambridge

University Press

week

1

2

3

4

5

6

7-8

Course Schedule

Topics

The Origins of language

The Development of Writing

The Properties of language

Primate Use of Language

The Sounds of Language

The Sound patterns OF Language

Exam 1, What is phonology

9

10

11-12

13-14

15

Word And Word-formation procsses

Morphology

Phrases and Sentences Grammar

Semantics

Syntax

The Origins of language

The Study of Language:

Language: is primarily a means of communicating thoughts

from one person to another.

The Origins of Language

While it is sure is that - unsurprisingly - spoken language

developed long before written language, no-one knows for

certain how language originated. There are, however, lots of

speculations about the origin of human language.

The Divine Source

The Natural Sounds Source

The Oral-Gesture Source

Physiological Adaptation

Speech and Writing

Links

The Divine Source

According to one view God created Adam and " whatsoever Adam

called every living creature , that was the name thereof " من ذلك.In most

religions there appears to be a divine source that provides humans with

language. In attempts to rediscover this original, However it seems that

children with no access to human speech simply grow up with no language

at all (see Chapter 14). NO SPEECH = NO LANGUAGE.

The Natural Sounds Source

Another speculation on the origin of language is that the first words were

imitations of natural sounds. It is true that there are onomatopoeic words

in every language, i.e. words that echo natural sounds, for example:

CUCKOO, SPLASH, BANG قرع, RATTLE خشخشة, BUZZ أزيز, etc.

Another idea is that the original sounds of language came from cries of

emotion, i.e. pain, anger and joy, for example: OUCH!

One another is the "yo-heave-ho theory" places the development of

human language in a social context and states that language originated in

The Oral-Gesture Source إيماء

Many of our physical gestures, using body

hands and face, are means of nonverbal

communication and are used by modern

humans, even with their developed linguistic

skills. The "oral-gesture theory" proposes an

extremely specific connection between

physical and oral gesture involving a

"specialized pantomime فن التمثيل اإليمائىof

the tongue and lips" (Sir Richard Page, 1930).

Physiological Adaptation

Some of the physical aspects of humans that make the production of

speech possible or easier are not shared with other creatures:

Human teeth are upright and roughly even in height. Human lips have an

intricate muscle interlacing. The human mouth is relatively small, can be

opened and closed rapidly and contains a very flexible tongue.

The human larynx ( حنجرةor 'voice box') is special as well as the pharynx

above the vocal cords can act as a resonator for any sounds produced.

The human brain is lateralized and has specialized functions in each of the

two hemispheres. The functions that are analytic, such as tool-using and

language, are largely confined to the left hemisphere of the brain for most

humans. All languages require the organizing and combining of sounds or

signs in specific constructions.

Speech and Writing

Many of the speculations on the origin of language deal with the

question of how humans started to interact with each other.

However there are two major functions of language use:

The interaction function has to do with how humans use

language to interact with each other socially or emotionally.

The transactional function has to do with communicating

knowledge, skills and information.

This transactional function will have developed, in part, for the

transfer of knowledge from one generation to the next. And

while there are cultures that rely mainly on their oral tradition, in

many cases, as speech by its nature is transient عابر, زائل, the

desire for a more permanent record must have developed:

The Development of Writing

The Development of Writing

In comparison to spoken language, writing is relatively new - it

was invented for the first time by the Sumerians of Mesopotamia

in about 3200 BCE. Indians of Mexico invented it

independently around 600 BCE, and the rise of Egyptian

and Chinese systems may have been independent as

well. Writing was certainly a great boon هبةto memetic

spread, greatly increasing the fidelity الدقةand the

fecundity مبدعof the memes that took advantage of it.

These issues have already been analyzed in Memetics

and Society. In this section we will examine writing

systems and how they might have developed

The term "meme" (IPA: [miːm], not "mem"), coined in

1976 by Richard Dawkins, refers to a unit of cultural

information that can be transmitted from one mind to

another. Dawkins said, Examples of memes are tunes, catchphrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building

arches.

A meme propagates ينشرitself as a unit of cultural

evolution analogous in many ways to the gene (the unit

of genetic information).

Often memes propagate as more-or-less integrated

cooperative sets or groups, referred to as memeplexes

or meme-complexes

Writing and Memetic Selection

The development of language as an adaptation for memes, not

genes, is still a speculative تفكريproposal. However, it is certain

that writing is a purely memetic adaptation - there are no genes

"for" writing proficiency (though there are some that impair

يتلفthis ability). Writing, of course, is a vast improvement upon

speech in terms of memetic fecundity and fidelity. Writing a

meme down greatly increases its likelihood of being read by

potential adherentsالتحام, and the very fact of being written may

encourage people to adopt certain memes, as in the cases in

which people insist that something is true because they read it in

the paper. Writing also improves on memetic fidelity by

liberating memes from fallible عرضة للخطأhuman memory;

memes that are written down are much less vulnerable to

confusions or elaborations in retelling, and therefore have a

much lower mutation تغير أساسىrate.

Writing probably actually developed through memetic

competition, in which slightly different systems

competed and those that were most successful were

adopted. Writing probably began as an accounting

system of marks on clay طينtablets or other media. As

such, it was probably not very standardized; each

merchant or accountant could in theory have his own

slightly different system of marking his tablets. Major

conventions such as direction and orientation of

markings may have been established in most languages

due primarily to historical contingencyاحتمال, but the

specifics of structuring the marks probably came about

via memetic selection.

Each person who used the marks

used them in a slightly different way;

some ways were easier to remember,

easier to write, or easier to read than

others, and so these memes got

copied, Eventually, this process

produced better and better writing

systems.

Types of Writing

There are three basic forms of writing systems:

logographic systems, which use symbols to represent

whole words; syllabary systems, which use symbols to

represent syllables; and alphabetic systems, which use

symbols to represent units of sound. Logographic

systems are the most intuitive بديهيfrom the perspective

وجهة نضرof a society on the cusp نقطة التقاءof

developing writing, and thus they tended to be the first

to arise. They also are most logical next step from the

marking system used by merchants and accountants.

(Incidentally, the fact that Chinese is a logographic

system is one piece of evidence for its independent

invention .

Logographic systems, while being highly intuitive at

first, quickly become extremely cumbersome متعب.

They are difficult to learn and give relatively few

pronunciation cues صبعبة-شبائكة. Moreover, they require

the invention of a new syllable every time a new word

is needed, and they make compound words and

complicated syntax much more difficult to write.

Finally, the complicated pictorial symbols must be

rendered almost perfectly in order to be legible, which

makes writing a time- and energy-consuming process.

The second system, the syllabary, is much rarer,

since it is an intuitive system only for a few

languages.

It is used in one variant of Japanese and was

developed by an extremely intelligent Cherokee,

Sequoyah, for use in writing and recording his

native language. His system, based very loosely on

English (at most he borrowed a few forms),

became so successful that the formerly illiterate

Cherokee tribe began publishing newspapers and

books in their own language.

The third system of writing, the alphabetic system, is the most

difficult to invent and the easiest to use. Many linguists believe it

was invented only once, by the Phoenicians, and then spread or

adapted to other languages. The system seems counterintuitive at

first, since its most basic units do not correspond to anything

meaningful in speech, but rather to an isolated sound. However,

the system uses the power of infinite combination to achieve its

success; whereas Chinese characters might take years to learn,

the standard Roman alphabet often takes only a few months for

children to memorize.

Moreover, when each letter represents a certain sound,

pronunciation is more easily inferred from the structure of a

word (though English pronunciation sometimes leaves speakers

confused). Finally, markers such as umlauts serve to increase the

power of a system by more carefully delineating the

In general, when logographic, syllabary , and

alphabetic systems compete, the alphabetic

system will tend to dominate because it can

express the most thoughts most efficiently.

Languages such as Japanese and Chinese will

probably eventually be outcompeted because

English - or another language based on an

alphabet, most likely the Roman one - is so much

easier to use. (This is not to say that English is

easy, only that the alphabetic system is most

efficient.)

Spelling and Writing

One of the pitfalls of an alphabetic system is

the proper spelling of each word. Regional

variations in pronunciation affect how

different speakers try to render their spoken

words into writing. Consequently, speakers

of the same language may find it impossible

to communicate via writing because of

differences in spelling.

The solution to this problem, of course, is to standardize

spelling whenever possible. This is another example of the

influences of memes: those spellings that are easiest to

remember are most likely to become standard.

Of course, plenty of modern English spelling is due primarily

to now-obsolete historical facts, but these spellings were most

likely quite logical to the English-speakers that originally

standardized spelling.

Moreover, sometimes illogical or difficult-to-remember spellings

(and grammatical rules) are retained for other memetic reasons:

they may confer prestige on those who observe them, serve as a

mark of education, or indicate a formal tone (compare through

and thru).

Early "creative spelling" in English has given way

to standardized spellings for the vast majority of

words, recorded in dictionaries and, more recently,

in computerized spell-checkers. Though some

variation in spelling remains, this primarily reflects

distinct dialects, rather than multiple accepted

spellings in a single dialect. For example,

American and British English vary systematically

in the spellings of certain words (American color

and British colour) and suffixes (American -ize and

British -ise).

The Properties of language

What properties differentiate human language from all

other forms of signaling and what properties make it a

unique type of communication system?

There have been a number of attempts to determine the defining

properties of human language and different lists of features can be

found.

The following is a slightly modified list of features proposed by the

linguist Charles Hockett:

1.Arbitrariness.

It is generally the case that there is no 'natural' connection

between a linguistic form and its meaning. For the majority of

animal signals, however, there appears to be a clear connection

between the conveyed message and the signal used to convey it.

Arbitrariness of the symbols. Any symbol can be mapped

onto any concept (or even onto one of the rules of the

grammar). For instance, there is nothing about the Spanish

word nada itself that forces Spanish speakers to use it to

mean "nothing". That is the meaning all Spanish speakers

have memorized for that sound pattern. But for Croatian

speakers nada means "hope".

2. Productivity.

This is the ability to produce and understand any number of

messages that have never been expressed before and that may

express novel ideas. In all animal communication systems, the

number of signals is fixed. ( closed communication systems).

3. Cultural Transmission.

The process whereby language is passed on

from one generation to the next. While it is

clear that humans are born with an innate

predisposition الميلto acquire language, it is

clear that they are not born with the ability to

produce utterances in a specific language,

such as English. The general pattern of

animal communication is that the signals

used are instinctive and not learned.

4. Discreteness. متميز, منفصل

This is the property of having complex messages that

are built up out of smaller parts

5. Displacement. تنحية و إزاحة

This refers to the ability to communicate about things

that are not present in space or time. Animal

communication is almost exclusively designed for a

particular moment, here and now. It cannot effectively

be used to related events, which are far removed in time

and place. Human language allows the users of language

to talk about things and events not present in the

immediate environment.

5 . Duality . ازدواجية

Language organized at two levels . This

property is called duality , or double

articulation .

1. A Mode of Communication (vocalauditory, visual, tactile or even chemical)

2. Semanticity.

The signals in any communication system

have meaning.

Study Questions:

1. What is the property, which relates to the

fact that a language must be acquired or

learned by each new generation? 2. Can you

briefly explain what the term "arbitrariness"

means as it is used to describe a property of

human language?

3. Which term is used to describe the ability

of human language-users to discuss topics,

which are remote in space and time?

3. Pragmatic function. واقعي

All systems of communication serve

some useful purpose, from helping the

species to stay alive to influencing others'

behavior.

4. Interchangeability. قابل للتبادل

The ability of individuals to both send

and receive messages.

4. What is the term used to describe the fact that,

in a language, we can have different meanings for

the three words "tack", "act" and "cat", yet, in

each case, use the same basic set of sounds?

5. A distinction is made between 'communicative'

and 'informative' signals. No mention is made of

the phenomenon known as 'body language'.

Would 'body language', or other aspects of nonverbal signaling, be considered 'communicative' or

'informative'?

6.

Hockett

(1963)

proposed

that

'prevarication' could be treated as a property

of language. In discussing this property, he

pointed out that "linguistic messages can be

false" and "lying seems extremely rare among

animals". Can you give reasons for or against

including prevarication (either deception or

misinforming) among the properties of

human language?

Primate Use of Language

Primate Use of Language

Created by Lauren Kosseff

Research concerning the ability of primates to

acquire language has profound implications for the

understanding of the evolution of the human

species. The acquisition of language in

primates may shed light on the development

of language in early humans. In this sense,

research of primate language and primate tool use

أسال ِفناoffer similar insight into our early ancestors

. األوائِ ِل

Many people believe that language is a unique capacity

of humans. Doubters of the ability of primates to use

language include renowned M.I.T. linguist Noam

Chomsky and cognitive scientist Steven Pinker.

Chomsky's Universal Grammar theory clearly defines

language as a skill limited to humans, the sole possessors

of the cognitive hardware which makes language

possible. َعلون اللغة

َ األصحا الوحيدون لألجهزةِ اإلدراكي ِة الذي يَ ْج

َ محتملةChomsky makes an analogy to flying in order to

illustrate his position on primate language: "Humans can

fly about 30 feet-that's what they do in the Olympics. Is

that flying?

The question is totally meaningless." Chomsky

and his followers theorize that the المتطلبات العصبية

للغةneural requirements for language developed in

humans after the evolutionary split between

humans and primates.

They base their argument on the ease with which

children acquire language in comparison to the

difficulty exhibited by primates. To Chomsky and

his followers, this shows the innate propensity for

language in children which is not present in

primates.

Pinker posits the argument that primates can be

trained to do incredible things, however, these trained

behaviors do not signify language ability. He believes

that the primates simply learn to press certain buttons in

order to receive rewards.

.

Dr. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh is a researcher who strongly

believes in the ability of primates to use language. One

of her most impressive observations involved a bonobo

chimpanzee named Kanzi.

Savage-Rumbaugh tried to no avail بال جدواto train

Kanzi's adoptive mother to use a keyboard of symbols.

The researchers were surprised to find that Kanzi had

been eavesdropping يتسنطon his mother's lessons and

had acquired a substantial vocabulary. From then on,

Kanzi was not given structured training like his mother,

but was taught while walking through the forest with his

trainers. By the age of 6, Kanzi had acquired a

vocabulary of 200 words and was able to construct

sentences by combining words with gestures or with

other words. Kanzi's most notable accomplishment

was captured on videotape: he was told, "Give the dog a

shot," and he proceeded to inject his stuffed dog with a

syringe.

Savage-Rumbaugh argues that Kanzi's language was

initially dependent upon contextual cues, but that once

he mastered a substantial vocabulary, he could respond

accurately to 70% of novel commands from a concealed

speaker.

Critics say that Kanzi's accomplishments are not proof

of language ability in primates because the crucial

element in language ability is production, not

ّ َيَقُو ُل النقّاد

ْ َإنجازات كانزي ل

comprehension. . برهان

يست

بأن

َ

َ

لَيسوا،الحاسم في قدر ِة اللغ ِة إنتا ُج

العنصر

قدر ِة اللغ ِة في قرو ِد ألن

َ

َ

فهما.

Observation of the vervet species of

monkeys in the wild offers support for the

ability of primates to use language.

The vervet monkeys have demonstrated the

most advanced primate system of

communication in their natural environment.

The sounds which the vervets produce as a

means of communication are instinctive and

not learned.

Sign Language

Sign language has been chosen as the

superior medium in which to conduct

language instruction for primates because

they are unable to vocalize language. Some

researchers hold the belief that primates are

simply not intelligent enough to speak. This

theory has lost credence as further research

with apes has demonstrated their tremendous

intellectual capacities in other areas .

Another possible explanation of the

inability of primates to acquire verbal

language, posited by Robert Yerkes, is that

Primates are not inclined ميبببالtowards

imitation of sounds and therefore cannot

learn verbal language. A final theory

suggests that the vocal cords of primates

are not capable of supporting the

production of language.

Washoe

Washoe is a chimpanzee who was taught to sign by her

caretakers, Allen and Beatrice Gardner. She was raised

in a friendly environment in which she learned sign

language both through imitation and instrumental

learning. Her language acquisition االستمالكwas notable

in several respects. Washoe was able to transfer signs to

a new referent without specific instruction. For

example, she learned the word "more" in relation to

tickling but was spontaneously able to apply the term to

another referent. Additionally significant was Washoe's

use of signs in combinations after learning only about 8

or 10 signs.

This spontaneous combination of signs seems

similar to the ability of human children to connect

words in sentences to which they have never

specifically been exposed. Washoe has

demonstrated reliable use of 240 signs.

A sign is deemed reliable when its use has been

recorded by three separate observers on 15

consecutive days. Her trainers have observed that

Washoe mostly uses her signs to discipline her

children and explain her concern about them.

and Loulis

...

Washoe adopted an infant chimp named

Loulis. No human sign language was used in

Loulis' presence during the first 5 years of her

life. Remarkably, Loulis nonetheless acquired

more than 50 signs by watching the other

chimps. Bob Ingersoll, who studied Washoe and

Loulis, observed that there was little active

teaching on the part of the adult chimps. Loulis'

language acquisition thus reflects the manner in

which human children acquire language.

The Gardners concluded from Loulis'

acquisition of language through

observation of the other chimps that:

"once introduced, sign language is robust

and self-reporting, unlike the systems

that depend on special apparatuses such

as the Rumbaugh keyboards or the

Premack plastic tokens."

Nim

Herb Terrace doubted that primate language is any

sort of equivalent of human language. He did not

believe that the findings of language acquisition and

use in Washoe, Loulis, and other primates were truly

symbolic of language acquisition. Instead, he

theorized that there were simpler explanations for the

behaviors which had been interpreted as language use

by primates (Morgan's Canon!). Terrace posited that

the primates were performing rote memorization tasks

similar to pigeons who are taught to peck at colors in

specific orders.

Terrace also thought that primates only signed in order to

please their trainers, not for the personal gratification of using

the signs. Terrace also says that a primate might learn to

connect a sign with food and reproduce the sign through

simple conditioning, just as Pavlov's dogs were conditioned to

salivate at the sound of a bell.

.

Therefore, Terrace decided to conduct his own study of

primate language use. He raised a chimpanzee, Nim, as a

human child and taught him sign language in the manner in

which Washoe had been taught. Nim did in fact demonstrate

some important aspects of language use.

He was observed using the signs for "angry" and

"bite" to express his displeasure, an important

observation in that it demonstrates the use of

arbitrary symbols to represent physical actions.

Despite his acquisition and use of numerous

signs, Terrace decided that Nim was incapable of

combining words to create novel ideas. The only

occasions in which Nim produced combinations

of signs were imitations of signs previously

produced by his trainers.

Central Washington University's

Chimpanzee and Human Communication

Institute

The CHCI at Central Washington University is home to a

family of 5 chimps who, according to their trainers, have

mastered the use of sign language and implement it in

conversations with each other and their trainers. The chimps

at CHCI use the signs alone and in combination with other

signs. One of the longest recorded sentences produced by a

chimp contained 7 signs! Chimps generally utilize( use ) their

signs in discussing aspects of family life. The trainers have

observed that young males frequently sign to talk about

games, such as tickle and chase. َ دغدغة ومطاردة

An important finding about primate language use at

the CHCI is that the chimps use signs to refer to

natural language categories. For example, the chimps

use one sign signifying "dog" to refer to all

dogs. This category generalization is similar to that

of children as they first begin learning to

speak. Chimpanzees have also shown that they are

able to create novel signs by combining signs to

convey a metaphorically مجبازيdifferent concept. For

example, one chimp at the CHCI was recorded

describing a watermelon as "drink fruit." Seems like a

pretty accurate description!

The CHCI is considering a couple of possible

continuations of their research, provided that

funding is available. One possible area of

exploration is the ability of chimps to use signs to

represent spatial relationships and their capacity

for taking on the position of another person (or

chimp). Additionally, the CHCI is considering

studying the ability of chimps to recognize breakdowns in conversations and to repair them, their

use grammatical markers, and their ability to

understand and use temporal signs

The CHCI also hopes to expand their

research to include the study of how to

apply the teaching of language to chimps

to assisting autistic children, who have

difficulty learning language. They also

hope that their research will be helpful in

studying the teacher-student relationship

in humans.

The Orang Utan Language Project

At the National Zoo, Orang utans are learning to

communicate in a language designed especially for

them. Their training began with flash cards and has

advanced to the use of computers with touch screens. Both

nouns and verbs are being taught with the goal of eventually

testing the Orang utans ability to develop syntactically

accurate sentences. The Orang utan Language Project

operates under the idea that the orang utans will learn the

language if they wish to use it to communicate with their

trainers and to control their environment.

As such, no coercion is used in teaching the language

The Sounds of Language,

The Sounds of Language (ch.5)

The organs of speech can be divided into the following

three groups :

1-The respiratory system :This comprises the lungs ,

the muscles of the chest and the wind pipe

2- The phonatory system : this comprises the larynx

.

3- The articulatory system : this comprises the nose

, teeth , tongue , roof of the mouth and the lips .

Epiglottis

, Vocal cords and , Glottis

The phonatory system :

The Larynx : it is commonly called the Adam's apple , situated at

the top of the wind pip .The air from the lungs has to come out

through the windpipe and the larynx. In the larynx are situated a

pair of lip-like structures. These are called the vocal cords

and these are placed horizontally from _ front to back. They are

attached in front and can be separated at the back. The opening

between the cords is called the glottis

The vocal cords can be opened and closed (because they can be

separated at the back) and when the two cords come very close

to each other, the glottis will be shut completely. In fact when we

swallow food or water, the vocal cords shut the glottis and thus

prevent the food or water from entering the windpipe.

When we breathe in and out, the vocal cords are drawn

wide apart and 'thus the glottis is open. The-air enters the

lungs or gets out of the lungs through the wide open

glottis-:

When we produce some speech sounds, the vocal cords

are wide apart and the glottis is open.

Such sounds produced with a wide – open glottis are

called voiceless sounds or breathed sounds (the latter term is

used because this is the position of the glottis for

breathing). The first sounds in the English words peel,

ten, keen, chin , fine, thin, seen, shine and hat are voiceless sounds

.

( During the production of certain speech sounds, the

vocal cords are loosely held together and the pressure of the

air from the lungs makes them open and close rapidly.

This is called the vibration of the vocal cords and the

sounds produced when the vocal cords vibrate are called

voiced sounds. All the sounds in the English words bead,

deed, girl, judge, vine, then ,zoo, measure, need, wing, red, yard

and well are voiced sounds. )

The vibration of the vocal cords is important for

another factor, too. The rate at which the vocal cords

vibrate is called the frequency

The production of speech sounds (P. 40-41)

Articulators above the larynx

All the sounds we make when we speak are the result of muscles

contracting. The muscles in the chest that we use for breathing

produce the flow of air that is needed for almost all speech

sounds; muscles in the larynx produce many different

modifications in the flow of air from the chest to the mouth.

After passing through the larynx, the air goes through what we

call the vocal tract, which ends at the mouth and nostrils. Here

the air from the lungs escapes into the atmosphere. We have a

large and complex set of muscles that can produce changes in

the shape of the vocal tract, and in order to learn how the

sounds of speech are produced it is necessary to become familiar

with the different parts of the vocal tract. These different parts

are called articulators, and the study of them is called

articulatory phonetics.

Fig. 1 is a diagram that is used frequently in the study of phonetics.

It represents the human head, seen from the side, displayed as though it

had been cut in half. You will need to look at it carefully as the

articulators are described, and you will often find it useful to have a

mirror and a good light placed so that you can look at the inside of your

mouth.

Fig. 1 The articulators

i) The pharynx is a tube which begins just above the

larynx. It is about 7 cm long in women and about 8 cm in men,

and at its top end it is divided into two, one part being the back

of the mouth and the other being the beginning of the way

through the nasal cavity. If you look in your mirror with your

mouth open, you can see the back of the pharynx.

ii) The velum or soft palate is seen in the diagram in a

position that allows air to pass through the nose and through the

mouth. Yours is probably in that position now, but often in

speech it is raised so that air cannot escape through the nose.

The other important thing about the velum is that it is one of

the articulators that

can be touched by the tongue. When we make the sounds

and the tongue is in contact with the lower side of the

velum, and we call these velar consonants.

iii) The hard palate is often called the "roof of the mouth".

You can feel its smooth curved surface with your tongue.

iv) The alveolar ridge is between the top front teeth and the

hard palate. You can feel its shape with your tongue. Its surface

is really much rougher than it feels, and is covered with little

ridges. You can only see these if you have a mirror small enough

to go inside your mouth (such as those used by dentists). Sounds

made with the tongue touching here (such as and ) are

called alveolar

v) The tongue is, of course, a very important articulator and it can

be moved into many different places and different shapes. It is

usual to divide the tongue into different parts, though there are no

clear dividing lines within the tongue. Fig. 2 shows the tongue on a

larger scale with these parts shown: tip, blade, front, back and

root. (This use of the word "front" often seems rather strange at

first.)

vi) The teeth (upper and lower) are usually shown in

diagrams like Fig. 1 only at the front of the mouth,

immediately behind the lips. This is for the sake of a

simple diagram, and you should remember that most

speakers have teeth to the sides of their mouths, back

almost to the soft palate. The tongue is in contact with

the upper side teeth for many speech sounds. Sounds

made with the tongue touching the front teeth are called

dental.

vii) The lips are important in speech. They can be

pressed together (when we produce the sounds ,

), brought into contact with the teeth (as in , ), or

rounded to produce the lip-shape for vowels like .

Sounds in which the lips are in contact with each other are called bilabial,

while those with lip-to-teeth contact are called labiodental.

The seven articulators described above are the main ones used in speech,

but there are three other things to remember. Firstly, the larynx could also

be described as an articulator - a very complex and independent one

.

Secondly, the jaws are sometimes called articulators; certainly we

move the lower jaw a lot in speaking. But the jaws are not

articulators in the same way as the others, because they cannot

themselves make contact with other articulators. Finally,

although there is practically nothing that we can do with the

nose and the nasal cavity, they are a very important part of our

equipment for making sounds (what is sometimes called our

vocal apparatus), particularly nasal consonants such as , .

Again, we cannot really describe the nose and the nasal cavity as

articulators in the same sense as (i) to (vii) above.

Phonetics:

The general study of the characteristics of

speech sounds is called phonetics. Our basic

interest will be in articulatory phonetics,

which is the study of how speech sounds are

made, or articulated.

Articulation: voiced and voiceless

Place of articulation (P.41-45)

The active articulator usually moves in order to

make the constriction. The passive articulator

usually just sits there and gets approached.

A sound's place of articulation is usually named

by using the Latin ajective for the active articulator

(ending with an "o") followed by the Latin

adjective for the passive articulator. For example, a

sound where the tongue tip (the "apex")

approaches or touches the upper teeth is called an

"apico-dental".

Most of the common combinations of active and

passive articulator have abbreviated names (usually

leaving out the active half).

These are the abbreviated names for the places of

articulation used in English:

bilabial

The articulators are the two lips. (We could say that the lower lip

is the active articulator and the upper lip the passive articulator,

though the upper lip usually moves too, at least a little.) English

bilabial sounds include [p], [b], and [m].

labio-dental

The lower lip is the active articulator and the upper teeth are the

passive articulator. English labio-dental sounds include [f] and

[v].

dental

Dental sounds involve the upper teeth as the passive

articulator. The active articulator may be either the

tongue tip or (usually) the tongue blade -- diacritic

symbols can be used if it matters which. Extreme

lamino-dental sounds are often called interdental.

English interdental sounds include [

] and [

].

This , thank

alveolar

Alveolar sounds involve the alveolar

ridge as the passive articulator. The

active articulator may be either the

tongue blade or (usually) the tongue tip

-- diacritic symbols can be used if it

matters which. English alveolar sounds

include [t], [d], [n], [s], [z], [l].

Post alveolar

Post alveolar sounds involve the area just behind

the alveolar ridge as the passive articulator. The

active articulator may be either the tongue tip or

(usually) the tongue blade -- diacritic symbols can

be used if it matters which. English postalveolars

include [

].

]

and

[

Ch , sh ,

Linguists have traditionally used very inconsistent

terminology in referring to the post alveolar POA.

Some of the terms you may encounter for it

include:

Palato -alveolar, alveo-palatal, alveolo-palatal, and

even (especially among English-speakers) palatal.

Many insist that palato-alveolar and alveo (lo)palatal are two different things -- though they

don't agree which is which. "Post alveolar ", the

official term used by the International Phonetic

Association, is unambiguous, not to mention

easier to spell.

retroflex

In retroflex sounds, the tongue tip is curled up and

back. Retro flexes can be classed as apico-post

alveolar , though not all apico –post alveolars need to

be curled backward enough to count as retroflex.

The closest sound to a retroflex that English has is [

]. For most North Americans,

the tongue tip is curled back

in [

]

, though not as much as it is in languages that have true retro

flexes . Many other North Americans use what is called a

"bunched r" -- instead of curling their tongues back, they bunch

the front up and push it forward to form an approximant behind

the alveolar ridge.

r,

palatal

The active articulator is the tongue

body and the passive articulator is the

hard palate. The English glide [j] is a

palatal.

Velar

The active articulator is the tongue

body and the passive articulator is the

soft palate. English velars include [k],

[g], and [

glottal

This isn't strictly a place of articulation, but they had to

put it in the chart somewhere. Glottal sounds are made

in the larynx. For the glottal stop, the vocal cords close

momentarily and cut off all airflow through the vocal

tract. English uses the glottal stop in the interjection

uh-uh

(meaning 'no'). In [h], the vocal cords are

open, but close enough together that air

passing between them creates friction

noise.

Note:

[w] is often called a "labio-velar". This

doesn't follow the POA naming convention - it does not mean that the active articulator

is the lower lip and you try to touch your soft

palate with it! A [w] is made up of two

different approximants: a bilabial

approximant and a (dorso-)velar approximant

pronounced simultaneously

Consonant parameters (continued)

Manners of articulation (P.45-52)

Constriction degree

Place of articulation refers to where the narrowing occurs -which active articulator gets close to which passive articulator.

Constriction degree refers to how close they get. The main

constriction degrees are:

*Complete closure and sudden release(

plosive ) : the active articulator touches the passive articulator

and completely cuts off the airflow through the mouth.

Simultaneously there is a velic closure , that is the soft palate is

raised , thereby shutting off the nasal passage of air . When the

active articulator is suddenly remove from passive articulator ,

the air escapes with small explosive noise .

Sounds produced with complete closure

and sudden release are called plosive : [p],

[p], [t], [d] ,[k ] , [ g ] .

*Complete closure and slow release : (

affricates )

If after blocking the oral and the nasal passages

of air , the oral closure is removed slowly .

Sounds produced with complete closure

and slow release are called affricates

Chin and jam

*Complete oral closure : ( nasal )

the active articulator touches the passive

articulator and completely cuts off the

airflow through the mouth .But the soft

palate is lowered thereby opening the nasal

passage of air .The lung air will escape

through the nose freely . Sounds produced

with complete oral closure are called

Nasals .

Sum , sun , sung

* Intermittent closure ( trill , rolled)

the soft palate is raised , thereby

shutting off the nasal passage of air .

the active articulator strikes against the

passive articulator several times with the

result that the air escapes between the

active and the passive articulators

Intermittently .

Sounds that are produced with a stricture of

Intermittent closure are called trill or rolled .

red , ran

* Just once and then quickly flaps

forward .

For some consonants the active articulator

strikes against the passive articulator just

once and then quickly flaps forward .Such

consonants are called taps or flaps .

Very

* Close approximation (fricative )

the active articulator is brought so closer to

the passive articulator that there is a very

narrow gap between them . the soft palate is

raised , thereby shutting off the nasal passage

of air . the result that the air escapes through

the narrow space between the active and the

passive articulators .

Five , vine , thin , sip , zip , sheep and hat

•Partial closure : The active and the passive articulators

are in firm contact with each other . the soft palate is

raised , thereby shutting off the nasal passage of air . if

the sides of the tongue are lowered so that there is

plenty of gap between the sides of the tongue and the

upper molar teeth , the air will escape along the sides of

the tongue without friction .

Sounds produced with complete closure in the

center of the vocal tract but with the air escaping

along the sides of the tongue without any frication

are called lateral .

The initial sound in the word love is lateral .

Open approximation : the soft palate is raised ,

thereby shutting off the nasal passage of air . If

the active articulator is brought close to the

passive articulator so that there is a wide gap

between them , the air will escape through this

gap without any frication .

Sounds that are produced with a stricture

of open approximation

Are called frictionless continuants and semi –

vowels

fricative: the active articulator doesn't touch the passive

articulator, but gets close enough that the airflow through the

opening becomes turbulent. English fricatives include [f], [

], [z].

approximant: the active articulator approaches the passive

articulator, but doesn't even get close enough for the airflow to

become turbulent. English approximants include [j], [w],

[

]

]

, and [l].

affricate: Affricates can be seen as a sequence of a stop and a

fricative which have the same or similar places of articulation.

They are transcribed using the symbols for the stop and the

fricative. If one wants to emphasize the affricate as a "single"

sound, a tie symbol can be used to join the stop and the fricative

(sometimes the fricative is written as a superscript).

Notes:

A stop cuts off airflow through the mouth. Airflow through the

nose does not matter -- you can have both oral and nasal stops.

Oral stops are often called plosives, including in the IPA chart.

Nasal stops are usually just call ed nasals.

Approximants that are apical or laminal are often called liquids

(e.g.,

[

], [l]).

Approximants that correspond to vowels are

often called glides (e.g., [j] corresponds to

[i], [w] to [u]).

English has the

affricates

[t

] and [d ].

The stop and the fricative halves of these affricates are

at the same place of articulation: the stop is in fact

postalveolar rather than alveolar. We could be explicit

about this and underline the [t] and [d] (in IPA, a minus

sign under a symbol is a diacritic meaning "pronounced

further back in the mouth"), but most phoneticians

believe this difference in the place of articulation is so

predictable that it doesn't have to be marked.

State of the glottis

For now, we can simply use the terms

"voiced" and "voiceless" to answer the

question of what the vocal cords are doing:

In voiced sounds, the vocal cords are vibrating.

In voiceless sounds, the vocal cords are not

vibrating.

Ultimately, we will see there are different

ways of being voiced or voiceless.

The vocal cords can do a number of things. They can:

be held so wide apart that the air makes no sound

passing through them. (This is nice when you have to

breathe 24 hours a day, but not as useful for speaking.)

be held closer together, so that the air passing through

them becomes turbulent. This quality of sound is called

breathiness. It is what is happening in aspiration and in

the sound [h].

be held together so that the air passing through them

causes them to vibrate. This is called voicing.

be held together so tightly that no air can pass through

at all, as in a glottal stop.

(By varying their tension and position, the vocal cords can also

produce many other effects like breathy voicing, creaky voicing,

and falsetto.)

What the vocal cords are doing is independent of what the

higher parts of the vocal tract are doing. For any place of

articulation and any degree of stricture, you can get two different

sounds: voiced and voiceless.

For example, [t] and [d] are formed identically in the mouth; the difference

is that the vocal cords vibrate during a [d] but not during a [t]. (The obvious

exception is the glottal place of articulation -- you can't vibrate your vocal

cords while making a glottal stop.)

In each cell of the IPA chart, the symbol for the voiceless sound is shown

to the left and that for the voiced sound to the right. Some rows only have

voiced symbols (e.g., nasals and approximants). You can write the

corresponding voiceless sound using the voiceless diacritic (a circle under

Nasality

The soft palate can be lowered, allowing air

to flow out through the nose, or it can be

raised to block nasal airflow. As was the case

with the vocal cords, what the soft palate is

doing is independent the other articulators.

For almost any place of articulation, there

are pairs of stops that differ only in whether

the soft palate is raised, as in the oral stop

[d], or lowered, as in the nasal stop [n].

Laterality

When you form an [l], your tongue tip

touches your alveolar ridge (or maybe your

upper teeth) but it doesn't create a stop

because one or both sides of the tongue are

lowered so that air can flow out along the

side. Sounds like this with airflow along the

sides of the tongue are called lateral, all

others are called central (though we usually

just assume that

The side of the tongue can lower to different

degrees. It can lower so little that the air passing

through becomes turbulent (giving a lateral

fricative like

[

] or [ ])

or it can lower enough for there to be no

turbulence (a lateral approximant). The [l]

of English is a lateral approximant.

Air stream mechanism

Speech sounds need air to move. Most sounds

(including all the sounds of English) are created

by modifying a stream of air that is pushed

outward from the lungs. But it's possible for the

air to be set in motion in other ways.

Sounds which use one of the other three most

common airstream mechanisms are called

ejectives, implosives, and clicks. We'll discuss

these possibilities later in the course.

Describing consonant segments

A consonant sound can be described completely by specifying

each of the parameters for place and manner of articulation. For

example, [k] has the following properties:

active articulator

passive articulator

constriction degree

state of glottis

nasal

lateral

airstream mechanism

tongue body (dorsum)

soft palate (velum)

stop

voiceless

no

no

normal

So [k] is a voiceless oral central dorso-velar stop.

What is phonology? First Exam

What is phonology?

Phonology is the study of how sounds are organized and

used in natural languages.

The phonological system of a language includes

* an inventory of sounds and their features, and

* rules which specify how sounds interact with each

other.

Phonology is just one of several aspects of language. It is

related to other aspects such as phonetics, morphology,

syntax, and pragmatics.

Here is an illustration that shows the place of phonology in

an interacting hierarchy of levels in linguistics:

Comparison: Phonology and

phonetics

Phonetics …

Is the basis for

phonological

analysis.

Phonology …

Is the basis for further

work in morphology,

syntax, discourse, and

orthography design.

Analyzes the sound

patterns of a particular

language by

Analyzes the

production of all

human speech

sounds, regardless determining which phonetic

sounds are significant, and

of language.

explaining how these sounds are

interpreted by the native speaker.

Models of phonology

Different models of phonology contribute to our

knowledge of phonological representations and

processes:

* In classical phonemics, phonemes and their possible

combinations are central.

* In standard generative phonology, distinctive

features are central. A stream of speech is portrayed as

linear sequence of discrete sound-segments. Each

segment is composed of simultaneously occurring

features

* In non-linear models of phonology,

a stream of speech is represented as

multidimensional, not simply as a linear

sequence of sound segments. These

non-linear models grew out of

generative phonology:

autosegmental phonology metrical

phonology lexical phonology

What is a phoneme?

A phoneme is the smallest contrastive unit in the

sound system of a language.

Phonologists have differing views of the

phoneme. Following are the two major views

considered here:

* In the American structuralist tradition, a

phoneme is defined according to its allophones

and environments.

* In the generative tradition, a phoneme is defined

as a set of distinctive features.

Comparison

Here is a chart that compares phones and phonemes:

Represented between brackets by convention.

Represented between slashes by convention.

A phone is …

A phoneme is …

One of many possible sounds in the A contrastive unit in the sound

languages of the world.

system of a particular language.

The smallest identifiable unit found A minimal unit that serves to

distinguish between meanings of

in a stream of speech.

words.

Pronounced in a defined way.

Example:

[b], [j], [o]

Pronounced in one or more ways,

depending on the number of

allophones.

Example:

/b/, /j/, /o/

Examples (English): Minimal pair

Here are examples of the phonemes /r/ and /l/ occurring

in a minimal pair

* rip

lip

The phones [r] and [l] contrast in identical environments

and are considered to be separate phonemes. The

phonemes /r/ and /l/ serve to distinguish the word rip

from the word lip.

Examples (English): Distinctive features

/p/ /i/

-syllabic +consonantal -sonorant +anterior -coronal -voice continuant -nasal+syllabic -consonantal +sonorant +high low -back -round +ATR -nasal

What is an allophone?

An allophone is a phonetic variant of a phoneme in a particular

language.

* [p] and [pH] are allophones of the phoneme /p/.

* [t] and [tH] are allophones of the phoneme /t/.

What is a phone?

A phone is an unanalyzed sound of a language. It is the smallest

identifiable unit found in a stream of speech that is able to be

transcribed with an IPA symbol.

What is a minimal pair?

A minimal pair is two words that differ in only one sound.

Sounds which differ: /p/ and /b/

* [lQp] ‘lap’

* [lQb] ‘lab’

Compare: Morpheme-morphallomorph and phoneme-phoneallophone

The relationship between a

morpheme and its morphs and

allomorphs is parallel to the

relationship between a phoneme and

its phones and allophones.

A morpheme is manifested as

one or more morphs (surface

forms) in different environments.

These morphs are called

allomorphs.

A phoneme is manifested as one

or more phones (phonetic

sounds) in different environments.

These phones are called

Syllables

We have seen how each spoken language has a set of

consonant and vowel categories that are used by its

speakers and hearers to distinguish the words of the

language. The consonants and vowels in turn are

combined into larger units, syllables. Syllables are

distinguished from one another in terms of the

consonants and vowels that they consist of. But

syllables can also be distinguished from one another in

other ways, and some of these ways are very commonly

used contrastively, that is, to distinguish words from

each other.

We will look at some of these

"suprasegmental" features of language in

this section. Languages also differ in

terms of how consonants and vowels

can be combined into syllables, the

"phonotactics" of the language, and we

will also look at this property of

languages in this section.

Phonotactics

As we have seen, each spoken language has

an "alphabet" of form categories —

consonant and vowel phonemes — which

are combined to form the syllables that make

up words. But languages differ not only in

the particular vowel and consonant

phonemes they have. They also differ with

respect to how the vowels and consonants

may be combined to form syllables.

Let's start with simple English syllables consisting of a

consonant followed by a vowel; I'll abbreviate this as

"CV". First, can any consonant appear in the "C"

position? Taking the vowel as the constant /o/, certainly

all of the following are possible syllables in English:

/po/, /bo/, /mo/, /vo/, /to/, /co/, /∫o/, /ko/, /lo/,

/ro/, /wo/, /ho/.

But what about /ηo/? A complete search of the English

lexicon reveals that there are no English words that have

syllables beginning with the phoneme /η/. Although

other nasal consonants (/m/ and /n/) and other velar

consonants (/k/ and /g/) can appear at the beginnings

of syllables, English seems to constrain syllables to not

begin with the phoneme /η/.

What about the vowels in a CV syllable? Let's be more specific and assume

that the syllable is stressed and comes at the end of an English word.

Keeping the consonant as the constant /b/, all of the following seem

possible: /bi/, /be/, /bu/, /bo/, /b⊃/, /bay/, /baw/, /b⊃y/. (For

speakers who do not make the distinction between /⊃/ and /α/, /bα/

would also be possible.) But what about the following: /bI/, /bε/,: /bI/,

/bε/, /bæ/, /bU/, /b^/, /bα/ (for speakers who distinguish /α/ and

/⊃/)? None of these syllables seems possible. Again there is apparently a

sort of prohibition on the kinds of phonemes that can appear in English

syllables. In this case, the most efficient way to state the prohibition is to

say that English forbids lax vowels, other than /⊃/, from appearing at the ends of

syllables (at least stressed syllables at the end of words). Note that /⊃/

presents a problem for the generalization; this is one of the ways in which

this vowel does not quite fit into the lax/tense, short/long distinction.

Thus English has constraints on the structure of

syllables. Such constraints are referred to as

phonotactics. It's beyond our goals to go into

English phonotactics in detail, but let's investigate

a bit further what the bounds are on English

syllables.

What about syllables with more than one

consonant at the beginning? In general, clusters

of consonants not separated by vowels are more

difficult for speakers to produce than consonants

that are separated by vowels.

This is because the articulators must move from

one consonant position to another without

opening up in between (because the opening

would be realized as a vowel). And the difficulty

of particular combinations varies considerably.

Thus we should expect more constraints on what

is possible in clusters than for single consonants.

An examination of the English lexicon reveals

that the following consonant clusters can appear

at the beginnings of General American English

syllables (my accent) if we count the semivowels

/w/ and /y/ as consonants.

/tw/, /dw/, /kw/, /gw/

/by/, /py/, /my/, /fy/, /vy/, /ky/, /hy/

/pl/, /bl/, /fl/, /kl/, /gl/, /sl/, /∫l/

/pr/, /br/, /fr/, /θr/, /tr/, /dr/, /kr/, /gr/

/sp/, /st/, /sk/, /sm/, /sn/, /∫p/

/spl/, /spr/, /str/, /skl/, /skr/

We can see some patterns in what is possible. /s/ seems to be

special. If we leave it out, we see that all of the clusters

end in a sonorant consonant, /w/, /y/, /l/, or /r/.

Clusters of three consonants must consist of /s/

followed by a voiceless stop followed by either /l/ or

/r/. In fact, for this and other reasons, /l/ and /r/ are

often treated as forming a category in their own right.

Co-articulation

Coarticulation in phonetics refers to two

different phenomena:

* the assimilation of the place of articulation

of one speech sound to that of an adjacent

speech sound. For example, while the sound /n/

of English normally has an alveolar place of

articulation, in the word tenth it is pronounced

with a dental place of articulation because the

following sound, /θ/, is dental.

* Elision is the omission of one or more sounds (such

as a vowel, a consonant, or a whole syllable) in a word or

phrase, producing a result that is easier for the speaker

to pronounce. Sometimes, sounds may be elided for

euphonic effect.

Assimilation (linguistics)

Assimilation is a regular and frequent sound change

process by which a phoneme changes to match an

adjacent phoneme in a word. A common example of

assimilation is vowels being 'nasalized' before nasal

consonants as it is difficult to change the shape of the

mouth sufficiently quickly.

If the phoneme changes to match the preceding

phoneme, it is progressive assimilation (also left-toright, perseveratory, or preservative assimilation). If the

phoneme changes to match the following phoneme, it is

regressive assimilation (also right-to-left or anticipatory

assimilation). If there is a mutual influence between the

two phonemes, it is reciprocal assimilation. In the

latter case the two phonemes can fuse completely and

give a birth to a different one. This is called a

coalescence.

The notion was identified by Sanskrit Grammarians as

Sandhi or fusion.

The notion was identified by Sanskrit Grammarians

as Sandhi or fusion.

Assimilation may result in the neighbouring segments

becoming identical, yielding a geminate consonant; this

is complete assimilation. In other cases, only some

features of phonemes assimilate, e.g. voicing or place

of articulation; this is partial assimilation.

Tonal languages may exhibit various degrees of tone

assimilation, while sign languages also exhibit

assimilation when the characteristics of neighbouring

phonemes may be mixed

English

Complete assimilation:

The word assimilation itself (from Latin ad + simile)

illegible (in + legible)

suppose (sub + pose)

Partial assimilation:

voicing: the pronunciation of absurd as apsurd or abzurd

devoicing: bats (bat + the plural morpheme s, which is

underlyingly /z/)

place of articulation: impossible (in + possible), incomplete (in

which n represents the velar nasal)

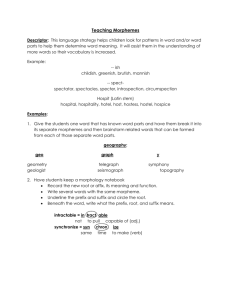

Word And Word-formation processes

Word - Formation Processes

One of the distinctive properties of human language

that we have already discussed in the introductory

chapter is creativity, by which we mean the ability of

native speakers of a language to produce and

understand new forms in their language. Even though

creativity is most apparent when it comes to sentence

formation, where new words are added to our mental.

In this part of Chapter 3 we discuss the processes that

speakers of a language use regularly (and

unconsciously too) to create new words in their

language

(1) Derivation اإلشتقاق

The most productive process of word formation in a

language is the use of derivational morphemes to form

new words from already existing forms, as we discussed

in the previous handout. So, for example, from arrange

we can derive rearrange, from which we can still derive

rearrangement. Can you think of other examples?

Derivation is the formation of a new word or

inflectable stem from another word or stem. It typically

occurs by the addition of an affix . An affix is a bound

morpheme that is joined before, after, or within a root

or stem

* A prefix is an affix that is joined before a root or

stem.(un- , pre- , mis- ) e.g ) The prefix un- attaches to

the front of the stem selfish to form the word unselfish

* A suffix is an affix that is attached to the end of a root

or stem

(-ful , -less , -ism) . e.g) The past tense suffix -ed attaches

to the end of the stem walk to form the past tense verb

walked.

* An infix is an affix that is inserted within a root. or

stem .

Philippines (Tagalog) The focus marker -um- is a infix which is

added after the first consonant of the root

· bili: root ‘buy’

· -um-: infix ‘AGT’

(2) Coinage ابتكار

Coinage is the invention of totally new

words. The typical process of coinage usually

involves the extension of a product a name

from a specific reference to a more general

one. For example, think of Kleenex, Xerox,

and Kodak. These started as names of

specific products, but now they are used as

the generic names for different brands of

these types of products.

(3) Conversion التحويل

Conversion is the extension of the use of one

word from its original grammatical category to

another category as well. For example, the word

must is a verb (e.g.

1 “You must attend classes regularly”), but it can

also be used as a noun as in “Class attendance is a

must”. Conversion from one category to another

is very common in natural language morphology

and it’s one way of enriching the lexicon of a

language.

(4) Borrowing

New words also enter a language through

borrowing from other languages. English, for

example, borrowed a lot of French words as a

result of the Norman invasion in 1066, and that’s

why the English lexicon has a Latinate flavor to it,

even though English did not descend from Latin.

Here are some examples of foreign words that

found their way into English:

(a) leak, yacht (from Dutch)

(b) barbecue, cockroach (from Spanish)

(c) piano, concerto (from Italian)

(5) Compounding

New words are also created through the common

process of compounding, i.e. combining two or

more words together to form a new complex

word. Here are some examples of compounding:

(a) post + card → postcard

(b) post + office → post office

(c) book + case → bookcase

We may also combine more than two words, e.g.

mother-in-law, sergeant-at-arms.

(6) Acronymsالمختصرات

Acronyms are words created

from the initial letters of several

words. Typical examples are

NATO, FBI, CIA, UN,

UNICEF, FAQ, WYSIWYG,

radar, laser

(7) Back-formation ) Back-formation

Back-formation of words results when a word is

formed from another word by taking off what

looks like a typical affix in the language. For

example, one of the very productive derivational

morphemes in English is –er, which may be added

to a verb to create a noun meaning “a person who

performs the action of the verb”, e.g. teacher,

writer. Sometimes, however, the reverse happens.

A noun enters the language first and then a verb is

“back-formed” from it. This is the case with the

verbs edit and televise

for example, which entered English as back-formations from

editor and television.

(8) Clipping القصاصة

Another process of word-formation is clipping, which is the

shortening of a longer word. Clipping in English gave rise to

words such as fax from facsimile, gym from gymnasium, and lab

from laboratory.

(9) Blending ال َم ْزج

Blending is another way of combining two words to form a new

word. The difference between blending and compounding,

however, is that in blending only parts of the words, not the

whole words, are combined. Here are some examples:

(a) smoke + fog → smog

(b) motor + hotel → motel

Morphology

Morphemes

Introduction

Morphemes are what make up words. Often,

morphemes are thought of as words but that is not

always true. Some single morphemes are words while

other words have two or more morphemes within

them. Morphemes are also thought of as syllables but

this is incorrect. Many words have two or more syllables

but only one morpheme. Banana, apple, papaya, and

nanny are just a few examples. On the other hand,

many words have two morphemes and only one syllable;

examples include cats, runs, and barked.

Definitions

morpheme: a combination of sounds that have a

meaning. A morpheme does not necessarily have to be a

word. Example: the word cats has two morphemes. Cat

is a morpheme, and s is a morpheme. Every morpheme

is either a base or an affix. An affix can be either a

prefix or a suffix. Cat is the base morpheme, and s is a

suffix.

affix: a morpheme that comes at the beginning (prefix)

or the ending (suffix) of a base morpheme. Note: An

affix usually is a morpheme that cannot stand

alone. Examples: -ful, -ly, -ity, -ness. A few exceptions

are able, like, and less.

base: a morpheme that gives a word its meaning.

The base

morpheme cat gives the word cats its meaning: a particular type

of animal.

prefix: an affix that comes before a base morpheme. The in

in the word inspect is a prefix.

suffix: an affix that comes after a base morpheme. The s in

cats is a suffix.

free morpheme: a morpheme that can stand alone as a

word without another morpheme. It does not need anything

attached to it to make a word. Cat is a free morpheme.

bound morpheme: a sound or a combination of

sounds that cannot stand alone as a word. The s in cats is a

bound morpheme, and it does not have any meaning without

the free morpheme cat.

inflectional morpheme: this morpheme can only be a suffix.

The

s in cats is an inflectional morpheme. An inflectional morpheme creates a

change in the function of the word. Example: the d in invited indicates past

tense. English has only seven inflectional morphemes: -s (plural) and -s

(possessive) are noun inflections; -s ( 3rd-person singular), -ed ( past tense), en (past participle), and -ing ( present participle) are verb inflections; -er

(comparative) and -est (superlative) are adjective and adverb inflections.

derivational morpheme: this type of morpheme changes the

meaning of the word or the part of speech or both. Derivational

morphemes often create new words. Example: the prefix and derivational

morpheme un added to invited changes the meaning of the word.

allomorphs: different phonetic forms or variations of a

morpheme. Example: The final morphemes in the following words are

pronounced differently, but they all indicate plurality: dogs, cats, and horses.

homonyms: morphemes that are spelled the same but have different

meanings. Examples: bear (an animal) and bear (to carry), plain (simple)

and plain ( a level area of land).

homophones: morphemes that sound alike

but have different meanings and

spellings. Examples: bear, bare; plain, plane; cite,

sight, site.

Fifteen Common Prefixes and Ten Common

Suffixes

The following tables and tip are adopted from

Grammar and Composition by Mary Beth Bauer,

et al.

Prefix

adcircumcomdedisexinin-

Meaning

to, toward

around, about

with, together

away from, off

away, apart

from, out

not

in, into

Prefix

intermispostresubtransun-

Meaning

between

wrong

after

back, again

beneath, under

across

not

Suffix

Meaning

-ly

-ment

-ness

in a certain way

the result of being

the state of being

the act of or the state

of being

without

-tion (-ion, -sion)

-less

Suffix

Meaning

-able (-ible)

-ance (-ence)

-ate

-ful

-ity

capable of being

the act of

making or applying

full of

the state of being

Tip

Suffixes can also be used to tell the part of

speech of a word. The following examples

show the parts of speech

indicated by the suffixes in the chart.

Nouns: -ance, -ful, -ity, -ment, -ness, -tion

Verb: -ate

Adjectives: -able, -ful, -less, -ly

Adverb: -ly

Morphology

Morphology is the study of word structure. For example in the

sentences The dog runs and The dogs run, the word forms runs and

dogs have an affix -s added, distinguishing them from the bare

forms dog and run. Adding this suffix to a nominal stem gives

plural forms, adding it to verbal stems restricts the subject to

third person singular. Some morphological theories operate with

two distinct suffixes -s, called allomorphs of the morphemes

Plural and Third person singular, respectively. Languages differ

wrt.

. to their morphological structure. Along one axis,

we may distinguish analytic languages, with few

or no suffixes or other morphological processes

from synthetic languages with many suffixes.

Along another axis, we may distinguish

agglutinative languages, where suffixes express

one grammatical property each, and are added

neatly one after another, from fusional languages,

with non-concatenative morphological processes

(infixation, Umlaut, Ablaut, etc.) and/or with less

clear-cut suffix boundaries

Morpheme

In morpheme-based morphology, a morpheme

is the smallest linguistic unit that has semantic

meaning.

In spoken language, morphemes are composed

of phonemes, the smallest linguistically distinctive

units of sound.

The concept morpheme differs from the

concept word, as many morphemes cannot stand

as words on their own. A morpheme is free if it

can stand alone, or bound if it is used exclusively

along side a free morpheme.

English example: The word

"unbreakable" has three morphemes

"un-", (meaning not x) a bound

morpheme, "-break-" a free morpheme,

and "-able". "un-" is also a prefix, "able" is a suffix. Both are affixes.

Types of morphemes

Free morphemes like town, dog can

appear with other lexemes (as in town

hall or dog house) or they can stand

alone, or "free".

Free morphemes fall into two categories .

First :The set of ordinary nouns , adjectives

and verbs this is called ( lexical morphemes

) eg) boy , man , sad , long , follow , break …

Second :This set consists largely of the

functional words in the language such as

conjunctions , prepositions and pronouns

this is called ( functional morphemes)

eg)and , but , on , near , the , that , it ……

Bound morphemes like "un-" appear only together with

other morphemes to form a lexeme. Bound morphemes

in general tend to be prefixes and suffixes.

Unproductive, non-affix morphemes that exist only in

bound form are known as "cranberry" morphemes,

from the "cran" in that very word. This also falls in two

categories :

First :Inflectional morphemes modify a word's tense,

number, aspect, and so on. (as in the dog morpheme if

written with the plural marker morpheme s becomes

dogs).

Noun +

-'s , -s

Verb +

-s , -ing , -ed , -en

Adjective +

-est , -er

Second: Derivational morphemes

can be added to a word to create (derive)

another word: the addition of "-ness" to

"happy," for example, to give "happiness." (

-less , -ness , pre- , un- , …..)

Allomorphs are variants of a morpheme,

e.g. the plural marker in English is

sometimes realized as /-z/, /-s/ or /- ɪz/.

Free morpheme

In linguistics, free morphemes are

morphemes that can stand alone, unlike

bound morphemes, which occur only as

parts of words. In the English sentence

colorless green ideas sleep furiously, for example,

color, green, idea, and sleep are all free

morphemes, whereas -less, -s and -ly are all

bound morphemes

Bound morpheme

Bound morphemes are morphemes that can occur

only when attached to root morphemes. Affixes are

bound morphemes. Common English bound

morphemes include: -ing, -ed, -er, and pre-.

Morphemes that are not bound morphemes are free

morphemes.