Käthe Kollwitz (July 8, 1867 – April 22, 1945) was a German painter

advertisement

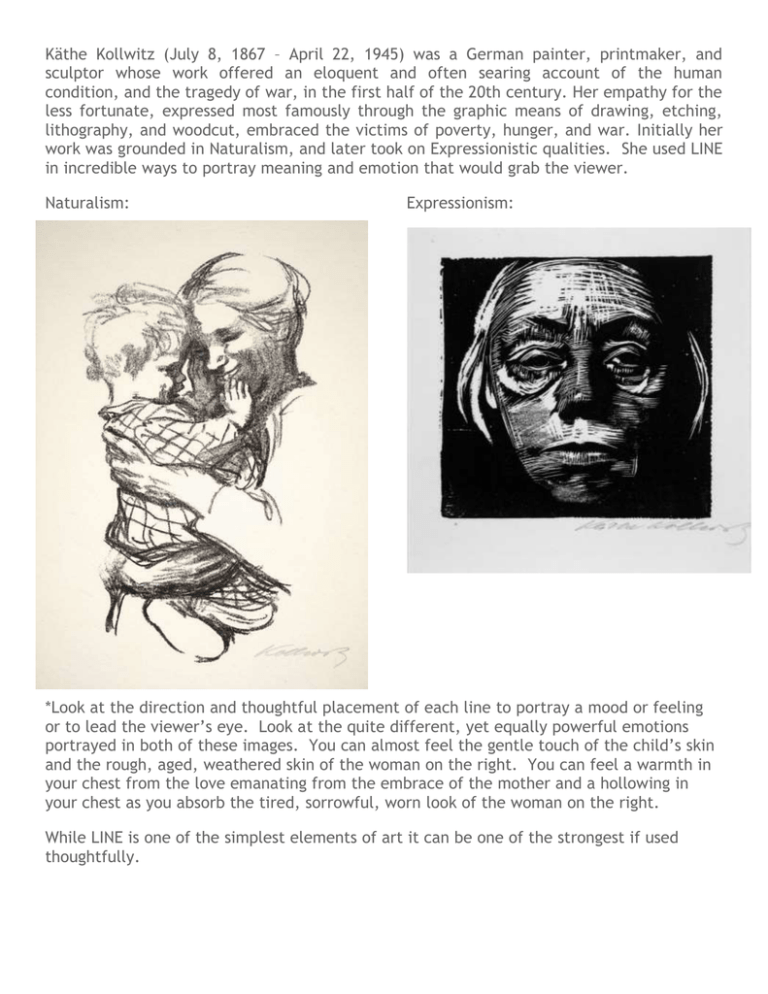

Käthe Kollwitz (July 8, 1867 – April 22, 1945) was a German painter, printmaker, and sculptor whose work offered an eloquent and often searing account of the human condition, and the tragedy of war, in the first half of the 20th century. Her empathy for the less fortunate, expressed most famously through the graphic means of drawing, etching, lithography, and woodcut, embraced the victims of poverty, hunger, and war. Initially her work was grounded in Naturalism, and later took on Expressionistic qualities. She used LINE in incredible ways to portray meaning and emotion that would grab the viewer. Naturalism: Expressionism: *Look at the direction and thoughtful placement of each line to portray a mood or feeling or to lead the viewer’s eye. Look at the quite different, yet equally powerful emotions portrayed in both of these images. You can almost feel the gentle touch of the child’s skin and the rough, aged, weathered skin of the woman on the right. You can feel a warmth in your chest from the love emanating from the embrace of the mother and a hollowing in your chest as you absorb the tired, sorrowful, worn look of the woman on the right. While LINE is one of the simplest elements of art it can be one of the strongest if used thoughtfully. More about the artist: Kathe Kollwitz is regarded as one of the most important German artists of the twentieth century, and as a remarkable woman who created timeless art works against the backdrop of a life of great sorrow, hardship and heartache. Kathe was born in 1867 in Konigsberg, East Prussia (now Kalingrad in Russia). She studied art in Berlin and began producing etchings in 1880 In 1881 she married Dr Karl Kollwitz and they settled in a working class area of north Berlin. In 1896 her second son, Peter, was born. From 1898 to 1903 Kathe taught at the Berlin School of Women Artists, and in 1910 began to create sculpture. In 1914 her son Peter was killed in Flanders. The loss of Peter contributed to her socialist and pacifist political sympathies. Kathe believed that art should reflect the social conditions of the time and during the 1920s she produced a series of works reflecting her concern with the themes of war, poverty, working class life and the lives of ordinary women. In 1932 the war memorial to her son Peter - The Parents - was dedicated at Vladslo military cemetery in Flanders. Kathe became the first woman to be elected to the Prussian Academy of Arts, but in 1933, when Hitler came to power, she was expelled from the Academy. In 1936 she was barred by the Nazis from exhibiting, her art was classified as 'degenerate' and her works were removed from galleries. Kathe’s son Peter was killed in the early days World War I in 1914 at the age of 19. In 1940 Karl Kollwitz died. In 1942 her grandson, Peter, was killed at the Russian front. In 1943 Kathe's home was destroyed by British bombing along with many of her works and she was evacuated from Berlin to Moritzburg, near Dresden. Kathe Kollwitz was informed of her son's death in action on 30 October. ‘Your pretty shawl will no longer be able to warm our boy,' was the touching way she broke the news to a close friend. To another friend she admitted, 'There is in our lives a wound which will never heal. Nor should it.' This feeling of loss and sorrow is seen in many of her later works. By December 1914 Kolhwitz, one of the foremost artists of her day, had formed the idea of creating a memorial to her son, with his body outstretched, 'the father at the head, the mother at the feet', to commemorate 'the sacrifice of all the young volunteers'. As time went on she attempted various other designs, but was dissatisfied with them all. Kollwitz put the project aside temporarily in 1919, but her commitment to see it through when it was right was unequivocal. 'I will come back, I shall do this work for you, for you and the others,' she noted in her diary in June 1919. Twelve years later, she kept her word: in April 1931 she was at last able to complete the sculpture. 'In the autumn - Peter, - I shall bring it to you,' she wrote in her diary. Her work was exhibited in the National Gallery in Berlin and then transported to Belgium, where it was placed, as she had promised, adjacent to her son's grave. There it rests to this day. The story of the pilgrimage of one mother and father to their son's grave stands for millions of others. In August 1932 a war memorial was unveiled at the Roggevelde German war cemetery, near Vladslo in Flemish Belgium: a sculpture of two parents mourning their son, killed in October 1914· It is the work of Kathe Kollwitz. There is no more moving monument to the grief of those who lost their sons in the war than this simple stone sculpture of two parents, on their knees, before their son's grave. She and her husband are on their knees before their son's grave. They are there to beg his forgiveness, to ask him to accept their failure to find a better way, their failure to prevent the madness of war from cutting his life short. In the spring of 1945, Kollwitz knew she was dying.' War', she wrote in her last letter, 'accompanies me to the end.' She died on 22 April 1945, two weeks before the end of World War II. The Parents From War The Mothers