The Ethics of War

advertisement

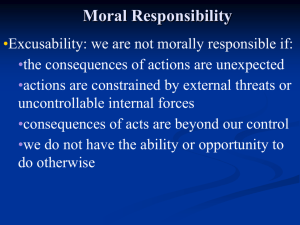

”The Ethics of War 3.forelesning Vènuste’s dilemma Vènuste: ”For four days I struggled with the terrible thought of how the family could cope with responsbility for the death of Thèoneste” • Is Vènuste reponsible for his brother’s death? • Did he do the right thing? Utilitarianism and the rules of war • What, from a moral point of view, ought to be the rules of war? • Is it ever morally right for a person to infringe ”ideal” rules of war? • The rule-utilitarian may take a two-level view: • - in justifying the rules, nothing but utilitarian considerations are in order • - in decision-making, the rules are absolutely binding Brandt: contractual utilitarianism • The utilitarian rules of war are the rules rational, impartial persons would choose as authoritative, given that they expected that their country at some time would be at war. • - impartial (here) = chosen behind a veil of ignorance • - autoritative = absolutely binding Brandt’s premises (1) Rational, impartial persons would choose certain rules of war (2) A rule of war is justified if and only if it would be chosen by rational impartial persons (3) The rules rational impartial persons would choose are ones which will maximise expectable long-range utility for nations at war Why prefer utilitarian rules? • If people are self-interested, they will choose rules that maximise expectable utility generally, since that will increase their chance of coming out best • If people are altruistic, they will choose the rules that maximise expectable utility generally (for that reason) Three types of rules • Humanitarian restrictions of no cost to military operation • Humanitarian restrictions possibly costly to military victory • Acceptance of military loss for humanitarian reasons Humanitarian restrictions of no cost to military operation • Unnecessary harm to civilian population • (unnecessary = does not decrease enemy military capacity and therefore does not increase probability of victory) • Murder and ill-treatment of POWs • Pillaging Humanitarian restrictions possibly costly to military victory Proper rule: substantial destruction of the lives and property of enemy civilians is permissible only when there is good evidence that it will significantly enhance the prospect of victory Acceptance of military losses for humanitarian reasons (1) When may one inflict large losses on the enemy to avoid smaller losses to oneself? (when the issue of war is settled) 1 a) Harm to enemy civilians balanced against own military losses 1 b) Harm to enemy civilians balanced against bringing war to end (2) Restrictions on the treatment of an enemy in cases where these do not affect outcome of the war? Morally permissible acts vs acts permitted by the rules of war • Morally permissible act (according to rule utilitarian theory of moral principles) = act which would not be forbidden by the kind of conscience which would maximise long-range expectable utility were it built into people as an internal regulator of their relations with other sentient beings, as contrasted with other kinds of conscience or or not having a conscience at all. How absolute are Brandts rules? • Acts in war are permitted of prohibited according to (1) Ideal rules (2) Actual rules (3) Morality Nagel: moral basis for the rules of war • Like Walzer: assumes that (some of) the (actual) rules of war express/embody ”deep morality” • => (some) rules of war are absolute • Difference between Brandt/Nagel on absoluteness of rules? Mavrodes: Convention-dependent obligations • War convention does not express morally relevant distinctions • Should be regarded as convention-dependent • Obligations are convention-dependent if (1) their moral force depends on enforcement of convention (2) there could have been a different convention, in which case we would not have the former obligations Absolute norms • • • • • What is an absolute norm? => must be fulfilled without any exeptions Ex: prohibition against murder ”Do not (intentionally) kill (the innocent)” Can be specified, that is, exceptions can be included in norm Absolute rights • Prohibition against murder expressed in language of rights (rights-norms) • There is an absolute right not to be (intentionally) killed (unless…) • Right-duty correlation (Hohfeldian relation) • An absolute right can never be justifiably infringed/overridden. • Infringement = violation. Analysing Nagel’s absolutism • Distinction between doing/allowing (i.e., between killing and letting die) • Avoid murder, not prevent murder, at all costs. • Hostile relations are (inter-)personal • Never treat people as mere means • Treatment must be appropriately suited to its target in order to be justified Justification of hostile act • Brandt: To (ideal) rational, impartial persons • Nagel: To (real) victims of the act • Nagel against Brandt: utilitarian justification to the world at large ignores the special relation to the victim • Brandt against Nagel: cannot require consent in individual cases The moral purity objection • Absolutism as moral self-interest, aimed at preserving one’s moral purity. BUT • The need to preserve one’s moral purity cannot be the source of an obligation. Can only sacrifice moral integrity if there is alredy something wrong with the act (i.e.,murder) • The idea that one can justifiably sacrifice one’s moral integrity is incoherent. If one is justified in sacrificing moral integrity, there is no sacrifice of moral integrity. Venustè, again • Did Vénuste do the right thing by killing his brother? Thresholds and tragedies • Nagel’s qualified absolutism: • There are (threshold) situations that render an absolutist position untenable • Cannot claim justification for the violation • Moral blind alley • Incoherence of moral thought • Ought does not imply can in dilemmas Conflicts of value • Pluralism of value • Values are incommensurable • No universal currency (lexical ordering or higher value (independent or not)) to appeal to in order to settle conflicts • Relative importance of values • Tragic cases: no overriding value