Finding of Inquest - Zahra Abrahimzadeh

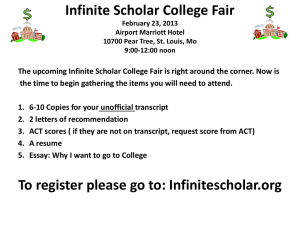

advertisement