Fodor Ch2z - Center for Cognitive Science

advertisement

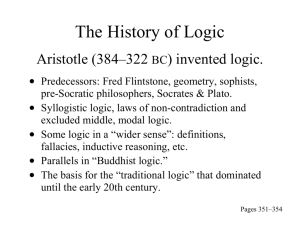

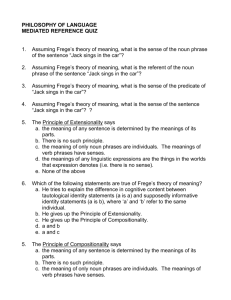

Chapter 2 Contrarian Semantics As we understand the jargon of Wall Street, a `contrarian’ is someone whose practice is to buy when everybody else thinks they should sell and to sell when everybody else thinks they should buy. In effect, contrarians believe that what more or less everybody else believes is false more or less all of the time. This book is an essay in contrarian semantics. Chapter 1 reviewed a spectrum of theories about the content of concepts (i.e. the intensions of concepts; i.e. the meanings of concepts ….etc) which, though they differ in all sorts of other ways, all agree that the content of a concept is whatever determines its extension. That’s to say: concepts C and C’ have the same content if and only if (C applies to a thing iff and only if C’ does.) However, sticky questions arise at once. For example, `is the content of concept C to be defined relative to the things that It actually applies to or to the things that it would apply to if there were such things? Philosophers love this kind of question; but in cog sci they aren’t often explicitly discussed. Our impression, for what it’s worth, is that it’s generally the `modal’ reading is that cog sci has In mind. Assume, for illustration, that there are no green cats. Still, the question arises: `would the extension of CA include a green domestic feline if there chanced to be one?’ Clearly, If your view is that the content of a concept is its definition, then your answer is `yes’. If, however, your view is that a concept is a stereotype, the answer is less clear: Stereotypic cats are domestic felines to be sure; but, one might have thought, since a green domestic feline would be strikingly unlike a stereotypic domestic feline; so perhaps it wouldn’t be a cat after all (unless, however, most actual cats were green, in which case it would be.) How these sorts of modal questions should be answered is, we think, is the fundamental difference between the view that concepts are stereotypes and the view that they are definitions. But we propose not to fuss over this since it will turn out, according to our own account, that there are no such things as intensions; that being so, we aren’s required to decide what the relation between intensions and extensions would be if there were. Chapter 1 arrived at the conclusion that none of the theories it considered work, and that there is no prospect of one that would. In this Chapter, we offer a diagnosis: they all fail to work because they are committed to `content determines extension’ (aka meaning determines extension), which we believe to be untrue. Now, at least in the cog sci community, our view is not just contrarian; it’s heretical.(fn) Indeed, it’s simply taken for granted that the arguments that meaning determines reference are decisive. So, what we propose to do first is show that they aren’t. Indeed, as far as we can tell, there any good reasons Fn There is some indication, however, that the tide has turned in Anglophone philosophy, where versions of `causal theories’ of reference are in vogue of late. For all sorts of reasons, however, the 1 kinds of causal theories of reference that are at present fashionable aren’t very like the kind that we will endorse in Part 2. (For an Anglophone philosospher who cleaves to the `intension is what determines extension’ tradition, see Frank Jackson (reference). for thinking that meaning determines reference; and, that being so, there are no good reasons for thinking that there is such a thing as meaning. Fn We won’t, however, discuss `possible world’ accounts of meaning. For one thing, such theories often grant what we are arguing for: viz that differences in semantic content are differences are in extension (the latter being defined over possible as well as actual worlds. More important, we can’t imagine how such theories might be naturalized; sets of possible worlds don’t cause things to happen. We start with what we (very loosely) call `Frege arguments’; (which we admit, have at most a tenuous connection to arguments that the historical Frege endorsed). `Frege arguments’ The paradigm is as follows: `If meaning didn’t determine reference, then coextensive concepts would ipso facto be cointensive (and, mutatis mutandis, coreferential words would be synonyms.) But there are, according to several standard and reasonable criteria, coextensive concepts that are not cointensive. So the content of a concept must consist of something more (or other) than its extension; and its intension is the only option.. We want to meet the Frege arguments head on, so we’ll just grant, for example, that `George Washington’ (hereinafter GW) and `Out First President’ (hereinafter OFP), though coextensive, aren’t synonyms. We’ll also grant a point that Frege emphasizes: substitution of one term for another, coxextensive, term need not preserve truth in `PA contexts’. a, ‘John doesn’t believe that G was OFP’ does not imply `John doesn’t believe that GW was GW’. The question is: What follows from that? In particular, even granting that coextensive terms needn’t be synonyms, and that the substation of coextensive in PA contexts need not preserve truth, how does that show that intensions determine extensions? There is, to begin with, more than a whiff of missing premise here. To make this sort of argument work, Frege needs not just the assumption that `GW’ and `OFP’ are coextensive (which the examples satisfy according to the historical consensus and which, in any case, Frege gets to stipulate for purposes of the argument) but also the assumption that if it isn’t coextension that guarantee synonymy, then it must be cointension that does. But, patently, that follows only if it’s likewise assumed that coextension and cointension are only candidates; what entitles Frege to assume that? We think, in short, that Frege’s sorts of examples do show that something more than coextension is required for a viable notion of conceptual content; but why concede that cointension is the mandatory alternative? This question becomes distinctly poignant if you think, as we do, that there is no plausible account of what cointension is (see Chapter 1); and that, even if there were, nobody has the slightest idea of how cointension, synonymy and the like might be naturalized (fn). 2 Fn It bears emphasis that, if there is indeed a circle of interdefinition that includes `cointension’, `synonymy`, `word meaning’ `conceptual content’ and the like, `coextension’ is in it too. Standard Frege understands the extension of a concept to be, more or less, the set of things that a concept applies too. But what does `applies to’ mean unless it means something semantic? What’s left, we think are `modes of presentation’ `guises’ and the like, much as Frege himself says. The difference is that Frege thinks understood such notions to be inherently semantic, and we don’t; we think that they can be understood in terms of non-semantic notions; in particular, in terms of causal notions. Consider, once again, John, who believes that GW was GW but does not believe that GW was OFP, so that, if you ask him who OFP was (and if J is feeling compliant) he will confidently answer that GW was; whereas, if you ask him who FOC was, he will say, quite sincerely, he doesn’t know. So far, everything works just the way a belief/intention psychology says that it should. However, `OFP’ and `GW’ are coextensive; both refer to GW. So if we take only extensions into account, to believe that GW is FP is to believe that GW was FOC. So why does John say that he doesn’t know who FOC was, when, in fact, he does know? Doesn’t that conflict with BI’s claim that one’s beliefs drive one’s behavior? Prima facie, if Frege’s sorts of examples show what Frege thinks they do, then they are counterexamples to BI. Either that, or they are counterexamples to the claim that B can we naturalized; which, so far as we’re concerned, is just as bad. If we read him right, Frege himself thought something like this: What John that GW was the FP when he (GW) is so described. But John doesn’t believe that GW was the FOC when he (GW) is described that way. That’s a perfectly coherent view as far as it goes; but the naturalization of BI requires that believing should be understood in terms of nonsemantic notions, and this demand surely isn’t satisfied unless `so described’ and the like are nonsemantic within the meaning of the act; describing something as such and such is, surely, a species of saying that it is such and such; and saying that something is such and such is saying that one believes that such and such; so we’re still in the semantic circle of interdefinitions. This line of thought depends, however, on taking it seriously that, J doesn’t believe that GW = OFP and, as a matter of cold fact, GW and OFP were the same guy. Now, to be sure, someone who wants to cleave to BI in face of the Frege examples, might insist that anyone in J’s situation does, after all, believe that GW was OFP. And, to be sure, there is a sense in which that’s so. There is a respectable sense in which somebody who believes that GW = GW does believe that GW = OFP if what’s going on in the world is that GW and OFP were the same person. So everything is fine; the supposed objection to BI has disappeared. The sound you now hear is of indefinitely many hard-headed cognitive scientist they don’t give a damn who wins word games; whether, in particular, there “is a sense of `believes’ ” in which someone in J’s situation believes that GW was OFP. What they give a damn about is, for example, how John’s beliefs cause his behavior. One help can’t but sympathize; but it just won’t do. J does say that he doesn’t know who OFP was, and we’re taking it that he says so sincerely. Nor is this a case like, for example, behavior 3 being driven by unconscious beliefs in the way that his verbal slips might be thought to be. So, if J really does believe that GW = FP, then his sincerely saying that he doesn’t is a prima facie counterexample to BI in a way that his verbal slips are not; the problem isn’t that Js belief that GW was FOC is in there, helping to cause his behavior, but somehow unavailable to his introspection; it’s that his belief that GOP = FOC isn’t `in there’ at all; that’s why it can’t cause his behavior. Roughly, his believing that GW was FOC, doesn’t count as one of J’s mental states in the sense that BI psychology has in mind when it says that one’s mental states cause one’s behavior. As Frege might say, `J doesn’t believe that GW was FOC when GW is `presented under the guise’ FOC; but J. does, of course, believe that GW was GW when GW is ‘presented under the guise GW’. But, though that seems OK, and though it’s OK for Frege to say that it doew, it’s not OK for us to say so. It’s the circularity/naturalization problem once again: For a guy to be `presented under the guise OFP is just for ’ is just that guy to be `so described’ `preseis itself a semantical notion. For Frege `J believes G was OFP’ and, to notions like `description` are about as semantic as any notion gets. Frege doesn’t mind that because he takes principles like `descriptions that are coextensive need not be synonymous, to be, as it were, at metaphysical ground level. Descriptions just are the kinds of things that can be coextensive but not cointensive; there is nothing more that can be said about that without using semantic/nonnaturalistic vocabulary; which, of course, is ipso facto unavailable to those of us who wish both to avoid circularity and to be naturists.; as we want to do and which even the hardest headed cognitive scientists also wants to do too. So now what ? The story we like is this: the form of words (1) is ambiguous. It has both the reading 2 and the reading 3. The point of present interest, however, is that though reading 2 makes 1 false, reading 3 makes 1 true: On the one hand; J doesn’t believe the proposition J GW is FOC; but, on the other hand, there’s a robust sense in which J does believe that GW was the FOC even though he sincerely denies that he does. After all, J believes the proposition that GW was our FP; and, in point of historical fact, the FP was the FOC. 1. J believes GW was the FOC. 2. J believes (the proposition) GW was FOC 3. GW was such that J believes, of GW, that he is the FOC. 4. John said “GW was the FOC” 5. GW is st J said he (GW) was the FOC. From the logico-syntactic point of view this is all is unsurprising; what’s happed is just that GW is moved from its `opaque` position inside the scope of the `so described’ operator (in 2) to a `transparent’ position outside the scope of `so described’ operator in (3). Since, according to the present treatment, being in the former position is what renders `GW’ inferentially inert in (2). It squares with this treatment that the rule substitution of coextensives is valid in 3 but not in 2. OK so far. 4 In fact, there’s plenty of precedent. Compare quoted expressions: Suppose what J uttered was 6; and suppose that, as a matter of fact, but unknown to J, the man with the Martini was GW. 6 . the man with the Martini is GW Then it’s unsurprising if J, (who, let’s say, believes the proposition that the man with the Martini is Abe Lincoln) can none the less perfectly sincerely, though falsely, deny that he said that Abe Lincoln was GW. One way to put it is that, although J does believe that the Martini-man was Abe L, he doesn’t know that he does. That’s not a paradox. GW = Abe follows from GW was the Martini-man only given a pertinent fact to which J. isn’t privy; namely that the man with the Martini = Abe. So , everything is fine: John ‘s denying that he believes (/said) that GW is Abe, isn’t, after all, a counter example to BI’s very plausible claim that what one believes drives one’s behavior. What the example does show, however, is the importance of distinguishing between, on the one hand: j said GW is Abe L when GW was described as the Martini-man (which is true) and, on the other hand, J said that GW was Abe when ABE wass described as the Martini-man. Or, to put the situation still differently, the example shows that, in one sense of `what you believe’, some of what you believe depends not only on `what’s going on in your head’ but also on `what’s going on in the world`. This theme will recur later in the discussion But though we hold that some story of that sort is true, there isn’t any story of that sort that we are allowed to tell. That’s because, as previously remarked, we aren’t allowed to use any semantic vocabulary in our construal of B/I explanations; and, of course, `proposition`, `true an d `so described’ all of which we used to disambiguate claims about what J believes/said, all count as semantic terms par excellence So the circularity/non-naturalizable dilemma persists in persisting: We need a Naturalistic and uncircular construal of what J believes/says and the like. But we haven’t got one. So now what? The suggestion we favor traces back at least to Carnap (references fn) Fn Though we don’t suppose he would approve of the way we use it. As we read him, Carnap was a Realist about Pas, but he was some sort of eliminativist about PA explanations, which he thought could be dispensed with in favor of brain science. We are officially neutral in respect to the first, but we’re morally certain that the second isn’t true. Here’s the basic idea of Carnap’s treatment: We should take very seriously the observation that names, descriptions and the like that are in the scope of expressions like `so described’, `as such`, `under the guise’, `under the mode of presentation….’ and so forth, work in much the way that quoted expressions do. To say that J believes that FOC, so described, was the FOC would be to say something like: J believes that tokens of the representation type `Our first President was the FOC’ are true; whereas, to say that J believes that GW was the FOC is to say something like: J believes that tokens of the representation type `GW was the FOC are true. In effect, Carnap’s idea is that quoted linguistic expressions might do the work that propositions are traditionally supposed do in explicating notions like conceptual content, belief etc. From the point of view of a logician whom the inferential inertness of PA contexts causes to lose sleep, that suggestion seems plausible. 5 Notice, in particular, that if Carnap is right, the `GW’ in 4 4’. J believes that the expression `father of our country’ applies to GW refers not to the father of our country but to the form of words `the Father of Our Country’ which is the one that is used (in English) to refer to the Father of Our Country. So if 1 says more or less what 4 does , then it’s unsurprising that 5 isn’t implied by 4, notwithstanding that GW was in point of fact the FOC and the principle that interchanging coreferring expressions preserves truth is valid. 5’. John believes that GW was that was the FOC it seems, at Quite generally, terms in quote marks don’t refer to what they do refer to when the quote marks are taken away. So quoted expressions are inert with respect (not just to substitution of coextensives but) to Existential Generalization, etc. We’re fond of Carnap’s answer to Frege’s question `why are PA contexts inferentially inert?’ because it invokes the independently plausible thesis that PAs are in some interesting way language-like. Both thoughts and sentences are, after all, systematic, productive and compositional; and the similarity between, on the one hand, the relation of thoughts to their constituent concepts and, on the other hand, the relation of sentences to their constituent words, is surely too striking to comfortably ignore. LOT argues for the assimilation of mental content to linguistic content, and comports with the assimilation of PA contexts to quotations. That’s the way things ought to work in empirical theory construction: everybody takes in everybody else’s wash. Or, if you prefer, no stick can hold hold itself up, but every stick holds up every other. But it bears, emphasis (in case you don’t like LOT) that. in principle, Carnap can do without the story about quotation. Technical details to one side, any cognitive theory that embraces RTM --- any cognitive theory according to which the relation between minds and propositions is mediated by mental representations--- can resolve Frege’s problem in much the way that Carnap does whether or not it assimilates the inferential innertness of PA contexts to that of quotation contexts. The basic point is that Frege’s sort of examples don’t show what he thought they do: that that thoughts and concepts must have intensions. The most they show is that their extensions can’t be the only parameter along which thoughts are individuated; there must be at least one other. Frege just took for granted that, since coextensive thoughts(/concepts) can be distinct, it must be differences in their intensions that distinguish them. However, RTM, in whatever form, suggests another possibility: that thoughts and concepts are individuated by their extensions together with their vehicles. The concepts THE MORNING STAR and THE EVENING STAR are distinct because the corresponding mental representations are: The mental representation that expresses the concept THE MORNING STAR has a constituent that expresses the concept MORNING, the mental representation that expresses the concept THE EVENING STAR does not. Likewise, the thought that Cicero was fat and the thought that Tully was fat are distinct because they contain different names of Tully (i.e of Cicero). Carnap’s assimilation of PA contexts to quotation contexts is, to be sure, a special case of this sort of explanation; but he can do without it so long as he cleaves to some version of RTM. The serious question about inferential inertness isn’t whether PA contexts are a species of quotation contexts; it’s whether you need differences among intensions to 6 individuate concepts (/thoughts), or whether any old differences of mental representations would do the job. Our next point is, even less encouraging to Carnap’s suggestion: Even if the quotation story is OK with a logician, a psychologist might well refuse to swallow it. The problem is that believing that the a certain token of the sentence type `Cicero was fat’ is true will have quite different psychological effects depending on whether it’s an English speaker that believes it. (fn) So the fn You can, of course, perfectly well believe that the sentence Ciceo was fat’ is true even if you have no idea what it means: someone whose opinions you respect points to a token of that sentence and says `that sentence is true). idea that belief is a idea is that belief is a relation between persons and people amd propositions that is mediated by LOT sentences seems to imply not just that anybody who can think that Cicero was fat must have a Language of Thought, but that they must all have the same language of thought; which is, as just remarked, a lot to swallow. This, is it seems to us, a parting of the ways. If you hold that differences among the vehicles of coextensive contents explains why coextensive PAs can be inferentially inert, then you will have to hold either that all of us who can think the proposition that Cicero was fat uses the same mental representation to do so, or that, quite possibly, we can’t all think that proposition. If you opt for the second horn, then if mental representations are expressions in the Language of Thought, and if, as we suppose there are no such things as intensions (hence no such thing as the intension of the thought that Cicero was fat) then it’s wide open that each think of us thinks in a different version of LOT, then each version of LOT is, in a reasonable sense, a private language. It is, to be sure, notorious that Wittgenstein thought that there can’t be such a thing as a private language; and that, over the years, lots of philosopher have agreed. But their consensus is, perhaps, less striking than it may seem since there isn’t much agreement about what it takes for a language to be private. One plausible reading is that Wittgenstein denied the possibility of a language that isn’t shared by a social group (Kripke apparently reads the `Private Language Argument’ that way REFERENCE) If that is the right interpretation of the PLA argument, then to endorse is, at a minimum, accept to hold that being a vehicle of interpersonal communication is an essential condition for being a vehicle of thought. The PLA would then be an a priori disproof of what is currently our best hope for a cognitive psychology. So be it; and so much the worse for the PLA. Hence such oracular remarks as “languages are spoken” (see Rush Reese REFERENCE) But anyhow, we were stuck with private languages (so understood) as soon as we said that there is no such thing as meaning. The idea that we can all think that Cicero was fat requires, at a minimum, that some of your thoughts translate into some mine; and, since it’s meaning that translation is supposed to preserve, no meaning, no translation. And, while we’re at it: no meaning, no communication, no meaning, no abridgment, no paraphrase…. and so forth for any of the cognitive process of which meaning preservation is taken to be a defining property. 7 We aren’t, of course, denying that --- in a rough, ready, and commonsensical sort of way, --- translation, communication, paraphrase, abridgement, synopsis and the like happen all the time. Of course they do. Our suggestion is, rather, that none of these is the name of a ‘natural kind’ of mental process. In which case, according to this view, there couldn’t be a theory of translation, communication, abridgement, synopsis etc, in anything like the way in which there are theories of photosynthesis, or glacial drift, or (maybe) evolution. In fact, we rather think that, deep down, everybody agrees that’s so; nobody really thinks that there’s a strict matter of fact, about what is the `right’ translation of a certain text; or whether two expressions are, strictly speaking, synonyms; or which of two metaphors is the better one; or which of two jokes is the funnier one; or whether a paraphrase misses something that’s essential to a text; or what, precisely, is the message transmitted in a certain communication exchange. Such decisions are endlessly sensitive to contextual detail; often enough they are matters of taste. (Hamlet told Ophelia to get herself to a nunnery. Critics have been arguing about what he meant by that for five hundred years are so; and the end is not in sight.) Probably you can’t say what a good metaphor, or translation, or synopsis is in any vocabulary that’s not already up to its ears in semantic notions (unlike, for example the vocabulary of neural science, or of biochemistry.) Compare E.O. Wilson’s remarkably naïve suggestion that science and criticism might eventually team up to answer such questions once and for all.) REFERENCE. If we’re right about all that, then it’s not just theories of conceptual content to which notions like translation, meaning and the like are unavailable; they aren’t available for the purposes of any strictly scientific and naturalistic enterprise. A serious theory and naturalistic theory of content might tell us what anaphora is; or what, if anything, generic nouns denote, or whether `the’ is a quantifier, or maybe even what the sufficient conditions for reference are. (We think that the vindication of cognitive science requires that it do the third of these). We don’t. however, expect it to tell us what a good novel is. We gave up on all that when we gave up on meaning. . What we’ve just been saying is intended to reply to a non-Fregian argument for the claim that mental (/linguistic) content has to be more than just referential; namely, that all sorts of notions that are routinely (and indispensably) used in talking about content can’t be translated into talk about reference; translation is itself among them. That doesn’t show that content is other than purely referential; but, on the other hand, even meaning nihilists (like us) really should grant that there is something that is more or less)preserved by translation, communication, paraphrase and the like. So, if it isn’t meaning, what is it? We’ll presently suggest a possibility that strikes us as appealing. Other arguments There is a scattering of other arguments that have, from time to time, been said to refute the suggestion that mental content is purely referential. None of these goes as deep as Frege’s observation that expressions in PA contexts are characteristically inferentially inert; in particular, that substitution of otherwise co-referential expressions isn’t reliably truth-preserving in such contexts. It is possible to particularly want to visit The Morning Star but not at all want to visit The Evening Star, even though…. etc. Our view is that this does show that there must be more to the individuation of mental 8 representations than their extensions. But it doesn’t show that the residuum is intension or meaning. We now propose to survey a couple of such alternatives to Frege’s sort of polemic. (fn) Fn The reader may suggest that, on closer consideration, some or all of these `alternatives’ are, in fact, themselves instances of Frege-arguments. That may be right; for present purposes, it doesn’t matter. `Empty` concepts There is no Devil and there are no unicorns; so one might reasonably claim that the concepts THE DEVIL and THE ONLY UNCORN IN CAPTIVITY are coextensive; both denote the empty set. And so too, mutatis mutandis, do the corresponding English expressions. But (so we suppose) THE DEVIL and THE ONLY UNICORN C are different concepts; nor are the expressions `the devil’ and `the only unicorn’ synonymous. So, once again the conclusion: there must be more to conceptual content (/lexical meaning) than extension. Now, we might complain that, strictly speaking, all of that is tendentious in one way or another. For example, the inference from `The Devil’ has no extension’ to ‘The Devil’ refers to the empty set’ is too quick (not to say incoherent). The empty set’ is after all, a set in good standing, so it does exist if any sets do. The right thing for say about `The Devil’ isn’t, therefore, that it refers to the empty set, but that it doesn’t refer at all. Still, you might reply, `The devil has no manners’ isn’t meaningless, and it isn’t a synonymy lf `the only unicorn has no maannter’; both of which it ought to be if meaning is reference. To which we reply: `We didn’t say that meaning is reference; we said that there is no such thing as meaning. You need an argument to gets from `The Devil’ and `TOU`’ mean nothing’ to `there is something that `The Devil’ and `TOU’ both mean’, and that inference strikes us as not promising. Shades of Alice in Wonderland. (fn) `But still, whether or not `The Devil’ and `the only unicorn’ are fn If you think this rejoinder is merely frivolous, we repeat: there is more to content than reference; but that doesn’t, in and of itself, argue that part of content is meaning. coextesnsive,the fact remains that they aren’t synonyms; why isn’t that enough to show that meaning can’t just be reference?’ Same reply: We didn’t say that reference is meaning; we said that there isn’t any such thing as meaning. Well, if there isn’t any such thing as meaning, there can’t be any such thing as synonymy since synonymy is, by definition, identity of meaning; in which case, there is no such thing as the synonymy of `The Devil` and TOU. We don’t think that the arguments just rehearsed are at allfrivolous, or that they are `merely philosophical’ in some invidious sense; but we can imagine that a hard-headed cognitive scientist might not agree. What’s true, in any case, is that they are all merely negative; we haven’t explained why, even if there is no synonymy, there is are there are more or less reliable `intuitions of synonymy’. If those aren’t really intuitions of identity of meaning, what are they intuitions of? (fn) fn Actually, the `inter-judge reliability` of intuitions about identity/difference of conentt isn’t selfevident. Linguists have been at daggers drawn for years about whether or not `John killed Bill’ and `John caused Bill to die (/to become dead?) are synonyms; or even whether it is possible for one to be true 9 when the other is false (which is not, by any means, equivalent to their having the same meaning.) We don’t propose to insist on this, but we think probaly somebody should.) It’s sometimes suggested, in aid of `Inferential Role’ accounts of meaning (see ch 1) that, at a minimum, they can explain how there could be differences in content between referentially empty concepts. Presumably anybody who knows what a `is a unicorn’ means should be willing to infer that if there aren’t any unicorns, then there aren’t any unicorn’s horns. But, because it’s possible to believe in unicorns but not in The Devil, someone might refuse to infer from `no unicorns’ to `no Devil’s horns’. Likewise, someone who hasn’t heard about the Morning Star being The Evening Star might reasonably decline the inference from `The Morning Star is uninhabited’ to `The Evening Star is uninhabited’. By contrast, if `bachelor’ and `unmarried man’ really are synonyms, then the inference from `is a bachelor’ to `is an unmarried man’ should be accepted by anybody rational who knows what the expressions mean. The identity of meaning with inferential role would, presumably, explain these facts; whereas, prima facie, the sort of meaning nihilism that we are preaching cannot. So far so good: if there are such things as inferential roles and if coextensive concepts (/expressions) can have different inferential roles, that would explain the (presumptive) intuition that coextensive concepts needn’t differ in content. So let’s suppose, for the purposes of argument, that there are such things as inferential roles (and that the worry, raised in Ch1. that inferential role semantics is intrinsically holistic can be coped with somehow or other.) In that case, there is, after all, a respectable argument for there being meanings, no? No. The suggestion that meaning is inferential role is subject to the same objection as all the other stories about what meaning is we’ve discussed so far: namely that since inference is itself a semantical notion, the suggestion is circular. For example, inference isn’t just any old case of one thought causing another; it’s a case of thought-to-thought causation that is generally truth preserving (associationists to the contrary notwithstanding). The hard part of figuring out what thinking is is to explain why it preserves truth when it does, and why it doesn’t when it doesn’t. And, of course, truth (like reference) is a mind/world relation. There is a way out of that for an inferential role semanticst to take; and just about all the cognitive scientists who endorse IRS do, In fact, take it. It’s to claim that the semantic content of a concept/PA) isn’t it’s inferential role but its causal. But we’ve been here before: `Surely not its whole causal role? Well, no; meaning is only that part of causal role that corresponds to analytic ). But `analyticity`, though vastly undefined, is surely also a semantic relation (since it surely it something to do with semantically necessary truth preservation. (fn) That’s the Fn Nor, by the way, is it all clear what `corresponds to ‘means’. Take all the mental causes and effects and disinterpret them. Now: which of the cause-effect pairs `correspond to’ truth-preserving inferences? Come to think of it, which of them correspond to inferences at all? traditional objection to IRS; we think it’s pretty convincing; and It holds, inter alia, for IR theories about empty terms, 10 CFor all that, perhaps you feel a certain nostalgia for the thought that something like inferential role is what is preserved in translation, synonymy, paraphrase, communication and the like. If so, we are prepared to split the difference: What is appealing about the idea that content and IRS are somehow the same thing can be retained without construing IRS as a theory of content. Here’s the idea: Matching conceptual roles are what good translation… etc. supervenene on; but they aren’t a supervenience base for Intentional content. That’s because (as previously remarked, there is no such thing as intentional content.) What goes on is something like this: Every concept has an extension; but also, each mental representation is surrounded by a (rather hazy) belt of connections between its tokenings and tokenings of other mental representations. Extensions must, of course, be preserved in translation, communication and the like; if I ask you for a mouse, an elephant won’t do; if y=you bring me an elephant, then you’re being mean; or perhaps you don’t know the difference between mice and elephants; most likely you just didn’t understand my request. But likewise, a rough alignment of our conceptual roles is a desideratum. Perhaps I believe, and you know that I believe, that gray mice are nice on toast but brown are not; and suppose that I believe, and you know that I believe, that it’s nearly time for lunch… and so forth. None of that is plausibly part of the content of our MOUSE concepts; not, at least, if content is supposed to connect, in the usual ways, with analyticity, truth preservation of truth in virtue of content, and the like. Still, the communication between us has been less than asuccess if, given my preferences, and given what you believe about my preferences, and given what I believe that you believe about my preferences… you bring me a brown mouse. We think this is the right way to think about the way that inferential roles connect to communication and, mutatis mutandis, other meaning preserving cognitive processes). That would explain why such processes are so invariably vague and open-ended and context-sensitive; in fact, why they aren’t, and quite probably can’t be, the domains of serious theories. And, we emphasize, you can have all that without supposing there are any relations at all between inferential roles and conceptual content. Even a meaning nihilist can have all that; for free. `One over many’ Plato worried about what it is that chairs have in common as such. That’s why he cared so much about defining `justice’: Maybe the reason that justice and are both grist for the philosophic mill is that both apply to things that satisfy their respective definitions. If so, there is after all a reasonable response to `why do we need meanings?’ Namely, its because some truths about which properties things have essentially are grounded in semantic truths. Roughly, metaphysics is just one damned analyticity after another. Our reply is uncharacteristically brief: We don’t believe a word of that. It is (as Kripke has remarked) typically inquiry that reveals essences. It was chemists who figured out essence of water; not lexicographers, and certainly not analytic philosophers. People who think that there is a semantic solution to Plato’s problem about the one and the many, do so because they think that the `what do chairs have in common as such?’ has an answer in a vocabulary that doesn’t include `chair’. But there isn’t. What chairs have in common as such is that they, and only they, are chairs. That, to a first approximation, is why we have a science about water but no science about furniture. 11 That’s all the arguments we can think of against our thesis that reference is all that there is to mental content. We end the chapter by providing what we take to be a knock-down argument that referemce must be all that there is to content: namely that reference is the only semantic relation of which we have a prayer of a Naturalistic account. The chapters that follow are devoted to providing a preliminary sketch of such an account. 12