Argumentum ad hominem

advertisement

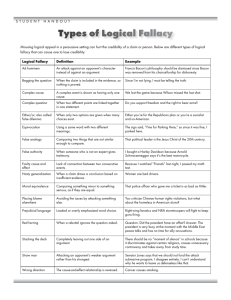

Rhetoric and Logic: The Great Debate Induction or inductive reasoning, sometimes called inductive logic, is the process of reasoning in which the premises of an argument are believed to support the conclusion but do not entail it; i.e. they do not ensure its truth. Induction is a form of reasoning that makes generalizations based on individual instances. It is used to ascribe properties or relations to types based on an observation instance (i.e., on a number of observations or experiences); or to formulate laws based on limited observations of recurring phenomenal patterns. Induction is employed, for example, in using specific propositions such as: •This ice is cold. (or: All ice I have ever touched was cold.) •This billiard ball moves when struck with a cue. (or: Of one hundred billiard balls struck with a cue, all of them moved.) ...to infer general propositions such as: •All ice is cold. •All billiard balls move when struck with a cue. Deductive reasoning is reasoning which uses deductive arguments to move from given statements (premises), which are assumed to be true, to conclusions, which must be true if the premises are true. An example of deductive reasoning, given by Aristotle, is • All men are mortal. (major premise) • Socrates is a man. (minor premise) • Socrates is mortal. (conclusion) Deductive reasoning is often contrasted with inductive reasoning, which reasons from a large number of particular examples to a general rule. Logical Fallacies: The best arguments are based in facts and reasoning. When a debater does not have the facts or good reasoning on his/her side, the debater will often offer other arguments to convince an audience. These other arguments often sound convincing, but they usually include falsehoods, or mistakes in reasoning that are called logical fallacies. A debater who plays to the crowd rather than to factual and logical argument is sometimes referred to as a sophist, and their debating style is termed sophistry. Sophists can still win debates, and all too often do. The better able an audience is to distinguish between logical and factual argument on the one hand, and logical fallacy and sophistry on the other, the better equipped that audience is not to be duped. Following are some of the most common logical fallacies and erroneous debate techniques. Proof by assertion is a logical fallacy in which a proposition is repeatedly restated regardless of contradiction. Sometimes this may be repeated until challenges dry up, at which point it is asserted as fact due to its not being contradicted (argumentum ad nauseam). In other cases its repetition may be cited as evidence of its truth, in a variant of the appeal to authority or appeal to belief fallacies. This logical fallacy is sometimes used as a form of rhetoric by politicians, or during a debate as a filibuster. In its extreme form, it can also be a form of brainwashing. Modern politics contains many examples of proof by assertions. This practice can be observed in the use of political slogans, and the distribution of "talking points," which are collections of short phrases that are issued to members of modern political parties for recitation to achieve maximum message repetition. The technique is sometimes used in advertising. The Big Lie: The technique is described in a saying, often attributed to Lenin, as "A lie told often enough becomes the truth", although the user may not be intentionally promoting a lie and may just believe an illogical or faulty proposition. The argument from ignorance, also known as argumentum ad ignorantiam ("appeal to ignorance") or argument by lack of imagination, is a logical fallacy in which it is claimed that a premise is true only because it has not been proven false or is only false because it has not been proven true. The argument from personal incredulity, also known as argument from personal belief or argument from personal conviction, refers to an assertion that because one personally finds a premise unlikely or unbelievable, the premise can be assumed not to be true, or alternatively that another preferred but unproven premise is true instead. Both arguments commonly share this structure: a person regards the lack of evidence for one view as constituting proof that another view is true. The types of fallacies discussed in this article should not be confused with the reductio ad absurdum method of argument, in which a valid logical contradiction of the form "A and not A" is used to disprove a premise. An argumentum ad populum (Latin: "appeal to the people"), in logic, is a fallacious argument that concludes a proposition to be true because many or all people believe it; it alleges that "If many believe so, it is so." In ethics this argument is stated, "If many find it acceptable, it is acceptable.“ This type of argument is known by several names, including appeal to the masses, appeal to belief, appeal to the majority, appeal to the people, argument by consensus, authority of the many, and bandwagon fallacy, and in Latin also by the names argumentum ad numerum ("appeal to the number"), and consensus gentium ("agreement of the clans"). It is also the basis of a number of social phenomena, including communal reinforcement and the bandwagon effect, and of the Chinese proverb "three men make a tiger": “Three men make a tiger" A government official, about to take a trip away from his office, worried that in his absence his opponents and critics would undermine him to his king. He went to his king and asked him whether he would hypothetically believe in one civilian's report that a tiger was roaming the markets in the capital city, to which the king replied no. He asked what the king thought if two people reported the same thing, and the king said he would begin to wonder. He then asked, "what if three people all claimed to have seen a tiger?" The king replied that he would believe in it. He reminded the king that the notion of a live tiger in a crowded market was absurd, yet when repeated by numerous people, it seemed real. He urged the king to pay no attention to those who would spread rumors about him while he was away. "I understand," the king replied, and the official left on his journey. Slanderous talk took place against him when he was away. When he returned, the king indeed stopped seeing him. Appeal to tradition, also known as proof from tradition, appeal to common practice, argumentum ad antiquitatem, false induction, or the "is/ought" fallacy, is a common logical fallacy in which a thesis is deemed correct on the basis that it correlates with some past or present tradition. The appeal takes the form of "this is right because we've always done it this way." An appeal to tradition essentially makes two assumptions: The old way of thinking was proven correct when introduced. In actuality this may be false — the tradition might be entirely based on incorrect grounds. The past justifications for the tradition are still valid at present. In cases where circumstances have changed, this assumption may be false. The opposite of an appeal to tradition is an appeal to novelty, claiming something is good because it is new. Argument to moderation (Latin: argumentum ad temperantiam, also known as middle ground, false compromise, gray fallacy, the golden mean fallacy) is a logical fallacy which asserts that a compromise between two positions is correct. The middle ground is often invoked when there are sharply contrasting views that are deeply entrenched. While an outcome that accommodates both parties to some extent is more desirable than an outcome that pleases nobody, it is not necessarily correct. The problem with the false compromise fallacy is that it implies that both extremes are always wrong, that only the middle ground is correct. This is not always the case. Sometimes only X or Y is acceptable, with no middle ground possible. Additionally any position can be invalidated by presenting one which is radically opposite, thus forcing the compromise closer to the desired conclusion. In politics, this is part of the basis behind Overton Window Theory: The concept of neutrality during wars, or various third way economic movements can sometimes be considered an argument for taking the middle ground. "Opinions on abortion range from banning it altogether to allowing it on demand; thus the correct view is restricted abortions.“ The potential outcome of the Judgment of Solomon in the Old Testament — when confronted with two women who each claimed the same baby to be their own — that the baby be cut in half and each purported mother given half. This was of course a plan to determine the true mother, but had it actually come down to cutting the baby in half, it would have been done on the false pretense that half for one, half for the other — that is to say, the middle ground — would have been a reasonable decision for the parties involved. "On the one hand, we have the Theory of Evolution, and on the other, we have the theory of Intelligent design. We should teach the controversy -- give both viewpoints equal time and consideration, rather than preferring one over the other." An ad hominem argument, also known as argumentum ad hominem (Latin: "argument to the man", "argument against the man") consists of replying to an argument or factual claim by attacking or appealing to a characteristic or belief of the person making the argument or claim, rather than by addressing the substance of the argument or producing evidence against the claim. The process of proving or disproving the claim is thereby subverted, and the argumentum ad hominem works to change the subject. It is most commonly used to refer specifically to the ad hominem as abusive, sexist, racist, or argumentum ad personam, which consists of criticizing or attacking the person who proposed the argument (personal attack) in an attempt to discredit the argument. It is also used when an opponent is unable to find fault with an argument, yet for various reasons, the opponent disagrees with it. Other types of the ad hominem include the ad hominem circumstantial, or ad hominem circumstantiae, an attack which is directed at the circumstances or situation of the arguer; and the ad hominem tu quoque, which objects to an argument by characterizing the arguer as a hypocrite. Ad hominem arguments are always invalid in syllogistic logic, since the truth value of premises is taken as given, and the validity of a logical inference is independent of the person making the inference. But, in law, the theory of evidence depends to a large degree on assessments of the credibility of witnesses. Evidence that a purported eyewitness is unreliable, or has a motive for lying, or that a purported expert witness lacks the claimed expertise can play a major role in making judgments from evidence. Argumentum ad hominem is the inverse of argumentum ad verecundiam, in which the arguer bases the truth value of an assertion on the authority, knowledge or position of the person asserting it. Hence, while an ad hominem argument may make an assertion less compelling, by showing that the person making the assertion does not have the authority, knowledge or position they claim, or has made mistaken assertions on similar topics in the past, it cannot provide an infallible counterargument. Appeal to motive is a pattern of argument which consists in challenging a thesis by calling into question the motives of its proposer. It can be considered as a special case of the ad hominem circumstantial argument. As such, this type of argument may be a logical fallacy. A common feature of appeals to motive is that only the possibility of a motive (however small) is shown, without showing the motive actually existed or, if the motive did exist, that the motive played a role in forming the argument and its conclusion. Indeed, it is often assumed that the mere possibility of motive is evidence enough. Poisoning the well is a logical fallacy where adverse information about a target is preemptively presented to an audience, with the intention of discrediting or ridiculing everything that the target person is about to say. Poisoning the well is a special case of argumentum ad hominem In general usage, poisoning the well is the provision of any information that may produce a biased result. For example, if a woman tells her friend, "I think I might buy this beautiful dress", then asks how it looks, she has "poisoned the well", as her previous comment could affect her friend's response. Ignoratio elenchi (also known as irrelevant conclusion or irrelevant thesis) is the informal fallacy of presenting an argument that may in itself be valid, but does not address the issue in question. Aristotle believed that an ignoratio elenchi is a mistake made by a questioner while attempting to refute a respondent's argument. He called it an ignorance of what makes for a refutation. In fact, Aristotle goes so far as to say that all logical fallacies can be reduced to what he calls ignoratio elenchi. Red herring Similar to ignoratio elenchi, a red herring is an argument, given in reply, that does not address the original issue. Critically, a red herring is a deliberate attempt to change the subject or divert the argument. This is known formally in the English vocabulary as Digression which is a neutrally connotated "Red herring". Blueback Herring Examples • Baseball player Mark McGwire just retired. He's such a nice guy, and he gives a lot of money to all sorts of charities. Clearly, he will end up in the Hall of Fame. The conclusion is ignoratio elenchi, since friendliness and charity are not the main qualifications for induction into the Hall of Fame. • I should not pay a fine for reckless driving. There are actual dangerous criminals on the street, and the police should be chasing them instead of harassing a decent tax-paying citizen like me. The existence of worse criminals is a secondary issue which has no bearing on whether the driver deserves a fine for recklessness. If the speaker were deliberately attempting to divert the issue, this would be an example of a red herring. While the argument about how the police should spend their time may have merit, the question of whom the police should prioritize pursuing and the question of what should be done with those the police have caught are separate questions. A straw man argument is an informal fallacy based on misrepresentation of an opponent's position. To "set up a straw man" or "set up a straw man argument" is to describe a position that superficially resembles an opponent's actual view but is easier to refute, then attribute that position to the opponent (for example, deliberately overstating the opponent's position). A straw man argument can be a successful rhetorical technique (that is, it may succeed in persuading people) but it carries little or no real evidential weight, because the opponent's actual argument has not been refuted. Its name is derived from the practice of using straw men in combat training. In such training, a scarecrow is made in the image of the enemy with the single intent of attacking it. Such a target is, naturally, immobile and does not fight back, and is not as realistic to test skill against compared to a live and armed opponent. Argumentum ad baculum (Latin: argument to the cudgel or appeal to the stick), also known as appeal to force, is an argument where force, coercion, or the threat of force, is given as a justification for a conclusion. It is a specific case of the negative form of an argument to the consequences. A fallacious logical argument based on argumentum ad baculum generally has the following argument form: If x does not accept P as true, then Q. Q is a punishment on x. Therefore, P is true. For example: If you do not believe that Jesus Christ is God, you will go to hell. Therefore, Jesus Christ is God. (Pascal’s Wager) Other Examples "I don't remember owing you any money. If I do not pay this supposed debt, you will beat me up and hurt my family. Therefore I do owe you some money." "Our political views are right and you should agree with them, because if you do not we will put you in a Gulag."