AP History 10 Henretta Chapter 4 I. New England's Freehold Society

advertisement

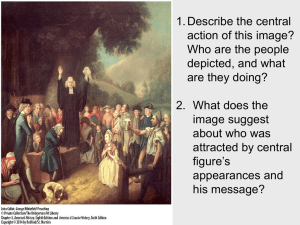

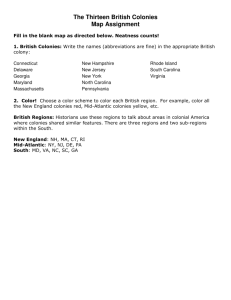

AP History 10 Henretta Chapter 4 I. New England’s Freehold Society A. Farm Families: Women in the Household Economy 1. Husband the head of the household – In The Well-Ordered Family (1712), Reverend Benjamin Wadsworth of Boston told women that it was their duty “to love and reverence” their husbands; girls learned from their mothers to be subordinate to their fathers; courts prosecuted more women than men for the crime of fornication. 2. Wife as the “helpmate” – Women assumed the role of dutiful helpmates; they tended gardens, spun thread and yard from flax and wool, wove cloth, knitted sweaters and stockings, made candles and soap, churned milk into butter, fermented malt for beer, preserved meats, and mastered dozens of other household tasks. 3. Motherhood – Most women married in their early twenties and had given birth six or seven times by their early forties. Fear of death during childbirth and the importance of baptism for the new baby were believed to be a reason many Puritan women clung to the church even when fewer men were attending. 4. Restrictions – No equality for women within the church; most women accepted such restrictions as social norms. B. Farm Property: Inheritance 1. Family authority – Emigrants wanted farms to provide for them and their grown children; landless children could be placed as indentured servants until age 18 or 21; landless men hoped to climb from laborer to tenant to freeholder. 2. Children of wealthy parents – Marriage portion was given when children of well-to-do farmers were in their early twenties; consisted of land, livestock, or farm equipment; enabled parents to choose their children’s spouses because economic concerns outweighed love in the long-term interests of the extended family. 3. Marriage – Bride gave her husband legal ownership of her property; she received a dower right to use but not sell one-third of the property if her husband died; this portion went to her children if she died or remarried. 4. Father’s duty – Was to provide an inheritance for his children or lose status in the community. Some men moved their families to the frontier where land was cheap and abundant; on the frontier, these men created communities of independent property owners. C. Freehold Society in Crisis 1. Population increase – Rapid natural increase doubled New England’s population each generation from 100,000 people in Puritan colonies in 1700 to nearly 400,000 in 1750; resulted in the division and subdivision of family farms to 50 acres or less. 2. Changes in family life – Parents could now only provide one child with an inheritance of land, which resulted in parents having less control over their children; increase in premarital sex and marriages arranged quickly due to pregnancy. Couples tried to limit family size or moved their new families into the frontiers of central Massachusetts, western Connecticut, and New Hampshire and Vermont. Wheat and barley were replaced with corn because it could feed people and provide nourishment for cattle and pigs. 3. “Household mode of production” – System of community exchange in which families swapped labor and goods; participants recorded debits and credits and “balanced” their accounts by exchanging only small amounts of currency, which was in short supply. II. Diversity in the Middle Colonies A. Economic Growth, Opportunity, and Conflict 1. Tenancy in New York – To attract migrants to an area inhabited largely by wealthy Dutch and English families, landowners granted long leases and the rights to sell improvements (houses, barns) to subsequent tenants; population grew slowly because migrants desired to own land; new tools such as the cradle scythe (1750s) increased the amount of grain produced but not enough to enable quick profits and land ownership. 2. Conflict in the Quaker Colonies – Early Quakers had settled in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, building simple homes and getting by with little. By the 1760s, wealthy landowners in eastern Pennsylvania were using slaves and poor immigrants on their farms; a new class of “agricultural capitalists” was forming out of men who were landlords, speculators, storekeepers, and large-scale farmers and whose presence marked the growing divisions between the social classes in the region. B. Cultural Diversity 1. Religious and ethnic diversity – The city of Philadelphia had more than 12 religious denominations present in 1748; migrants married within their ethnic groups (though Huguenots were a major exception); large population of wealthy Quakers helped to shape the culture of Pennsylvania and western New Jersey; pacifists purchased land from Native Americans rather than seizing it; advocated the abolition of slavery. 2. The German Influx – More than 100,000 German migrants settled in the Pennsylvania/western New Jersey region in the 17th and 18th centuries; settled in Lutheran and Reformed communities; discouraged from marrying outside of their ethnicity; advocated married women having the legal right to hold property and write wills, as they did in Germany. 3. Scots-Irish Settlers – Largest group of migrants came from Ireland, numbering about 115,000. Some were Irish and Catholic, but most were Scots and Presbyterians who had faced religious and economic repression by the English; settled in Pennsylvania region for religious tolerance; retained cultural practices. C. Religion and Politics 1. Religious Diversity – Orthodox church officials of several religions brought intolerance to the colonies. In America, religious groups enforced acceptable behavior through communal self-discipline. Quaker marriage rules maintained that couples have land and livestock; wealthy Quakers encouraged marriage among their children, while the poor remained single or married later in life. As Quaker population declined by 1750s, religious groups seeking increased political power (Lutherans and Baptists) had bitter conflicts raging among them. III. Commerce, Culture, and Identity A. Transportation and the Print Revolution 1. Improved transportation networks – From 1700 to 1750, colonies transformed by dramatic increases in shipping in the north Atlantic and construction of new networks of roads; transportation networks carried people, merchandise, information, and printed matter. 2. Print revolution – In 1695, British government surrendered the power to censor all printed materials; printers in England responded with a flood of newspapers, pamphlets, handbills, advertisements, scientific treatises, novels, and other printed matter; publications crossed the Atlantic and colonies began to create their own new publications, which facilitated the development of colonial identity and solidarity. B. The Enlightenment in America 1. The European Enlightenment – Emphasized the power of human reason; appealed to urban artisans, well-educated from merchant and planter families; 17th-century teachings of Copernicus (earth traveled around the sun). Philosophers used empirical research and scientific reasoning to study social institutions and human behavior; four fundamental principles: law-like order of the natural world, power of human reason, natural rights of individuals (self-government), and the improvement of society through progress. 2. John Locke – English philosopher; wrote Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), stressing the importance of environment and experience on human beliefs and behavior; argued that change was possible through education, thought, and action; hisTwo Treatises on Government (1690) argued that political authority did not come from divine right but from social compacts with the people who have the power to change their government. 3. Franklin’s Contributions – Born in Boston in 1706, Franklin was the exemplar of the American Enlightenment; shaped by Enlightenment literature and not the Bible. Franklin became a “deist” and believed that a Supreme Being (or Grand Architect) had created the world and then allowed it to operate by natural laws but did not intervene in people’s lives; rejected the divinity of Christ and the authority of the Bible; instead relied on “natural reason,” or the innate moral sense to define right and wrong. C. American Pietism and the Great Awakening 1. Pietism – An evangelical Christian movement that stressed a personal relationship with God; attracted farmers and urban laborers; appealed to “believers hearts rather than their minds.” 2. New England Revivalism– In the 1730s, Jonathan Edwards in the Connecticut River Valley preached the helplessness of men and women; his sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” (1741), spoke of “Hell’s wide gaping mouth” and his promotion of conversions; successfully incited religious fervor in the region. 3. Whitefield’s Great Awakening – Spoke from memory about the power of God and the need to seek salvation; followers were called “New Lights” for their claim that they felt a new light in them after hearing Whitefield preach. D. Religious Upheaval in the North 1. Old Lights and New Lights – Old Lights (conservative ministers) condemned the crying and fainting of New Lights in revival meetings and the New Light practice of women speaking in public; New Lights withheld tax payments from Old Light churches; new enthusiasm for religion led to the founding of schools for ministers (Princeton, Columbia, Brown, and Rutgers); people felt new power to be part of the religious experience. 2. Challenges to authority – Great Awakening challenged authority of all ministers; gave new sense of authority to the many who felt more justified in expressing religious and political opinions. E. Social and Religious Conflict in the South 1. The Presbyterian Revival – New Lights challenged the Church of England in the South; ritual displays of wealth became less meaningful as competition existed between the churches; Virginia governor denounced New Lights as offering “false teachings.” 2. The Baptist Insurgency – In the 1760s, thousands of white farmers converted to Baptist (adult baptism); Whitefield encouraged slaveholders to bring the enslaved to church, but many whites opposed; free blacks in Virginia embraced the church’s teachings; Baptist churches continued to grow in spite of these pressures; ministers spread teachings among slaves and began to shrink the cultural divide between white and black. IV. The Midcentury Challenge: War, Trade, and Social Conflict, 1750–1763 (Key events: British war against French in America, surge in trade increased American debt to British, and an increase in westward migration led to violence and rebellion.) A. The French and Indian War 1. Conflict in the Ohio Valley – In the 1750s, French authorities, alarmed by British inroads into Ohio, build a string of defensive forts; British Governor Dinwiddie dispatched military expedition led by George Washington to reassert British claims; result was an international incident that prompted Virginian and British expansionists to demand war. 2. The Albany Congress – In June 1754, delegates from British colonies met in Albany to discuss relations with the Iroquois and French expansion; Franklin proposed a “Plan of Union” with a continental assembly to manage trade, Indian policy, and defense in the western territories to counter French expansion; Franklin’s effort failed; war between France and England seemed imminent. 3. The War Hawks Win – Rising British statesman William Pitt and Lord Halifax in England wanted a war in North America with the French; fighting began June 1755; expanded to Europe by 1756 with Britain vowing to destroy France’s ability to compete economically. B. The Great War for Empire 1. The Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) – Pitt directed the war successfully from England, controlling both the commercial and military strategies; British had stunning successes and acquired Cuba and the Philippines from Spain, French Senegal, Martinique and Guadeloupe (eventually returned to France). The Treaty of Paris of 1763 ending the war gave Britain control of over half of North America, including French Canada. 2. Pontiac’s Rebellion – British acquisitions in North America frightened the Native American population, who believed that they would lose more territory to Anglo-American migrants; inspired by a Delaware prophet (Neolin), the Ottawa chief Pontiac, with a group of loosely affiliated tribes, launched an uprising against the British. Though Pontiac’s rebellion was put down, the Proclamation of 1763 prohibited white settlement west of the Appalachians; this edict was largely ignored by colonists. C. British Industrial Growth and the Consumer Revolution 1. Resources – Since 1700, Britain had become the dominant commercial power in the Atlantic and Indian oceans. By 1750, it was also becoming the first nation to use manufacturing technology and work discipline to expand output. Mechanical power was key to Britain’s Industrial Revolution; artisans designed and built water mills and steam engines that powered a wide array of machines: lathes for shaping wood, jennies and looms for spinning and weaving textiles, and hammers for iron forging. 2. American consumers – Soon Americans were purchasing 30 percent of all British exports. To pay for British manufactures, mainland colonists exported tobacco, rice, indigo, and wheat; New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia supplied wheat to Europeans; profits from exports enabled colonists to buy goods from England. Americans became more dependent on overseas credit and markets. D. The Struggle for Land in the East 1. Land disputes – Rising population of colonies meant more land needed; disputes over land and tenant uprisings broke out in Hudson River Valley of New York, in New Jersey, and in some southern colonies. Courts favored wealthy landowners; increasingly, the landless moved west to the Appalachian Mountains region. E. Western Rebels and Regulators (Movement of landless into the west meant clashes over Indian policies, political representation, and debts.) 1. The South Carolina Regulators – During Seven Years’ War, Anglo-American and Scottish settlers in South Carolina clashed with Cherokee; so-called Regulators were vigilante landowners who demanded that South Carolina’s eastern-controlled government provide western districts with more courts, fairer taxation, and greater representation in the assembly for those who had settled the region. The South Carolina Regulators were unsuccessful in gaining power from the eastern elite. 2. Civil Strife in North Carolina – 1766 saw a significant economic crisis in North Carolina as tobacco prices fell. To avoid losing their land, mobs of farmers (also called “Regulators”) closed the courts and intimidated judges; the Regulators proposed a series of reforms, including legislation to lower their legal fees and taxes. In May 1771, North Carolina’s royal governor sought to suppress the rebellion; violence ensued, ending with thirty men dead and seven Regulator leaders executed.