Power Point Presentation

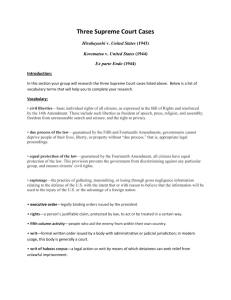

Separate But Equal:

The History of Segregation in the Law

TM

Brown v. Board of Education of

Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

JUDGES

If you were responsible for selecting all of the judges in

Florida, what would you look for?

Knowledge

Skills

Disposition/Qualities

TM

JUDGES

How are judges different from other elected officials such as legislators?

TM

JUDGES

Should judges be influenced by political pressures when deciding a case?

Would you want a judge to make a decision based on the law or how the public might react to the decision?

Should judges do what is legally right or should they do what is popular?

TM

JUDGES

JUDGES MUST FOLLOW:

FEDERAL CONSTITUTION

STATE CONSTITUTION

STATUTES

RULES

HIGHER COURT DECISIONS (PRECEDENT)

TM

JUDGES

So, a judge cannot decide a case based on how he/she feels about an issue.

TM

JUDGES

If a judge does not follow the existing law, his/her decision is subject to review by an appellate court.

All courts are subject to review by a higher court

except

for the highest court in the country: the Supreme

Court of the United States.

TM

Today, you will be a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court and decide a real case involving the Fourteenth

Amendment.

TM

But first –

You need to know about the

Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

TM

§ 1 of the Fourteenth

Amendment

All persons born or naturalized in the United

States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United

States ; nor shall any State . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws .

TM

Fourteenth Amendment

What are “privileges” or “immunities”?

What does “equal protection” mean?

TM

Privileges and Immunities

Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1872)

In the mid-19th century, New Orleans was plagued by health concerns stemming from slaughterhouses located within the city.

In response, the Louisiana legislature passed an act that required all slaughterhouses in New Orleans to move to a specific area and be operated by a private corporation chartered by the State.

TM

Privileges and Immunities

Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1872)

Over 400 butchers sued the State of Louisiana as well as the private corporation in multiple actions, alleging, in part, a violation of the privileges or immunities clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Each of the state trial courts ruled in favor of the

State and/or the private corporation, and the

Louisiana Supreme Court affirmed those decisions.

TM

Privileges and Immunities

Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873)

The United States Supreme Court affirmed the decisions of the Supreme Court of Louisiana.

The Court held that the Privileges or Immunities

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment affected only rights of United States citizenship and not state citizenship.

The Court further held that the amendment was primarily intended to protect former slaves from discriminatory laws and could not be so broadly applied as to restrict the police powers of the state.

TM

“Equal Protection”

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1879)

West Virginia passed a law which excluded African-

Americans from serving on juries. Strauder was a black man who had been convicted by an all-white jury in West Virginia state court.

Strauder challenged his conviction as being in violation of the Equal Protection Clause due to the

State’s failure to allow African-Americans to serve on his jury.

After losing his challenge in the West Virginia trial court, Strauder appealed to the Supreme Court of

Appeals of West Virginia, which affirmed his conviction.

TM

“Equal Protection”

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1879)

The case was then appealed to the United

States Supreme Court, which reversed the decision below.

A majority of the High Court held that the categorical exclusion of all African-Americans from juries for no other reason than their race was a violation of the Equal Protection

Clause.

TM

“Equal Protection”

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1879)

The Court did, however, limit its holding to race:

“We do not say that within the limits from which it is not excluded by the amendment a State may not prescribe the qualifications of its jurors, and in so doing make discriminations. It may confine the selection to males, to freeholders, to citizens, to persons within certain ages, or to persons having educational qualifications.

We do not believe the Fourteenth Amendment was ever intended to prohibit this.”

TM

§ 5 of the Fourteenth

Amendment

The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

TM

Enforcement of 14th Amendment

After the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment,

Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

The act provided that "all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement; subject only to the conditions and limitations established by law, and applicable alike to citizens of every race and color, regardless of any previous condition of servitude."

TM

Enforcement of 14th Amendment

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883)

Five separate cases, each involving an African-

American individual who had been denied access to hotels, theatres, or railway cars, were consolidated before the United States Supreme Court.

Ruling in favor of the discriminating private property owners, the High Court held:

Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment does not give

Congress the power to regulate private actors, just states.

The Thirteenth Amendment applies to private actors only so far as it precludes them from owning slaves, but not with regard to discrimination.

TM

TM

Separate But Equal

Part I

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163

U.S. 537 (1896)

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S.

537 (1896)

In 1890, Louisiana passed a law that provided:

“[A]ll railway companies carrying passengers in their coaches in this State shall provide equal but separate accommodations for the white and colored races by providing two or more passenger coaches for each passenger train, or by dividing the passenger coaches by a partition so as to secure separate accommodations.”

TM

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S.

537 (1896)

On June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy boarded a railway car designated for white patrons only.

Although Plessy was born a free person and was one-eighth black and seven-eighths white, under a Louisiana law he was classified as black, and thus required to sit in the "colored" car.

Plessy refused to leave the “white” car and was subsequently arrested and jailed.

TM

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S.

537 (1896)

Plessy was tried in Louisiana state court for violating the Louisiana statute.

Plessy argued that the state law requiring railroad companies to segregate trains denied him his rights under the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments.

The judge presiding over his case held that Louisiana had the right to regulate railroad companies as long as they operated within state boundaries.

Plessy subsequently filed a petition for writ of prohibition with the Louisiana Supreme Court, which was denied.

TM

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S.

537 (1896)

On appeal to the Supreme Court of the

United States, the High Court affirmed.

In a 7-1 decision, a majority of the Court held that the provision of “separate” but

“equal” private services, as mandated by state government, did not violate the

Fourteenth Amendment.

TM

Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78 (1927)

Martha Lum, a nine-year-old child of Chinese descent, was prohibited from attending an allwhite public school in Mississippi solely because of her descent.

Lum’s father petitioned a Mississippi state court for a writ of mandamus to force the Board of Trustees of the public school system to allow her to enroll in the all-white school. He asserted that she had been improperly classified as “colored.”

The trial court granted the request and allowed

Lum to enroll.

TM

Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78 (1927)

The Board of Trustees petitioned the

Mississippi Supreme Court to reverse the trial court’s decision.

The Mississippi High Court agreed with the

Board, reversed the trial court's decision, and allowed the Board of Trustees to exclude Lum from the all-white school.

Lum’s father appealed to the United States

Supreme Court.

TM

Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78 (1927)

The United States Supreme Court affirmed, unanimously holding that Lum’s father had not established a denial of equal protection of the laws when his daughter was placed in classes with other

“colored” races. According to the Court, those races had been “furnished facilities for education [that were] equal to that offered to all.”

TM

Gaines v. Canada ,

305 U.S. 337 (1938)

The University of Missouri Law School refused admission to Lloyd Gaines solely because he was an African-American.

At the time, there was no law school available to

African-Americans within the State of Missouri.

After Gaines alleged that this refusal violated his Fourteenth Amendment rights, the state of

Missouri offered to pay for Gaines’ tuition at the law school of an adjacent state. Gaines rejected this offer.

TM

Gaines v. Canada ,

305 U.S. 337 (1938)

Gaines filed a petition for writ of mandamus in Missouri state court asking the trial court to compel the law school to admit him.

The trial court denied relief. Gaines appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court, but that court affirmed the trial court’s denial of the petition.

TM

Gaines v. Canada ,

305 U.S. 337 (1938)

On appeal to the United States Supreme

Court, the High Court reversed.

A majority of the Court reasoned that because Missouri did not have an alternative means for African-Americans to obtain a legal education, the State was required to admit him to an all-white law school.

TM

Sweatt v. Painter , 339 U.S.

629 (1950)

Heman Marion Sweatt was denied admission to the University of Texas Law

School because the Texas Constitution expressly prohibited integration.

Sweatt sought a writ of mandamus in

Texas state court. Instead of issuing the writ, the trial court delayed the case for six months to allow the state to create a law school for African-Americans.

TM

Sweatt v. Painter , 339 U.S.

629 (1950)

After the creation of the law school,

Sweatt asserted that the two schools were not “equal” and insisted on admission to the all-white law school.

The trial court denied the petition, a Texas appellate court affirmed the denial, and the Texas Supreme Court denied a writ of error.

TM

Sweatt v. Painter , 339 U.S.

629 (1950)

The United States Supreme Court reversed, holding that the inequality between the two law schools violated the

Fourteenth Amendment.

To establish inequality, the Court cited a number of tangible factors, including number of faculty, books in the library, and access to extracurricular activities.

TM

Sweatt v. Painter , 339 U.S.

629 (1950)

The Court also relied on intangible factors:

“ The law school, the proving ground for legal learning and practice, cannot be effective in isolation from the individuals and institutions with which the law interacts.

Few students and no one who has practiced law would choose to study in an academic vacuum, removed from the interplay of ideas and the exchange of views with which the law is concerned . . . With such a substantial and significant segment of society excluded, we cannot conclude that the education offered [Sweatt] is substantially equal to that which he would receive if admitted to the University of Texas Law School.”

TM

Separate But Equal

Part II

TODAY’S CASE:

Brown v. Board of Education of

Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

TM

Separate But Equal

Before we discover how the United States

Supreme Court decided Brown, ask yourself the following questions and provide written answers based upon the cases we have discussed:

TM

Separate But Equal

How are the facts of this case similar to

Plessy, Lum, Gaines, and Sweatt?

How are they different?

What did the Equal Protection Clause mean after those four cases were decided?

TM

Now you are Justices on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Here is the question before the court…

Separate But Equal

CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTION:

Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other

“tangible” factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities?

TM

Separate But Equal

Individually answer the question –

Yes or No – based on the facts of the case, the constitution, and case precedent.

-Give 3 reasons in writing.

Separate But Equal

If you answer “Yes” – you are deciding for Brown.

_____________________________

If you answer “No” you are deciding for the Board of Education.

Separate But Equal

•

•

•

•

•

•

Form groups of 5

Choose a Chief Justice

Chief Justice Maintains Order

Poll the Justices. How did each one of you answer the questions and why?

Try to reach to a unanimous decision. Did the State’s actions violate the Fourteenth Amendment?

You have 10 minutes to discuss then take a final poll.

Separate But Equal

After each Court decides:

Bring the Chief Justices to the front of the room to report on the decision of each group

Tally results and announce

Separate But Equal

CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTION:

Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other

“tangible” factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities?

TM

Separate But Equal

What did the real U.S.

Supreme Court decide and why?

TM

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka,

347 U.S. 483 (1954)

In a unanimous decision, the United

States Supreme Court held that the

“separate but equal” doctrine in the field of public education is unconstitutional and violates the

Fourteenth Amendment. The Court reasoned that segregation, in and of itself, was harmful to African-American students. The Court rejected its prior approval in Plessy of the “separate but equal” doctrine.

TM