Symphony No. 7 in E Major Anton Bruckner (1824

advertisement

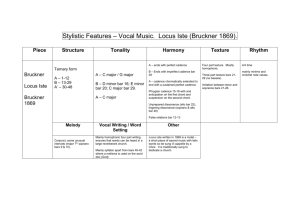

Symphony No. 7 in E Major Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) The Seventh Symphony, uniquely, enjoyed immediate and warm success in Bruckner’s lifetime, success that came as a happy and restorative surprise to this much-battered composer. Speaking to today’s audiences with singular directness, it remains the most loved of the nine—or ten, or eleven, depending on whether you count the symphonies before the official No. 1. Bruckner begins with an unmistakable assertion of E major. This takes the form of a soft, nonarticulated hum, a background for an event rather than an event in its own right. This is also a declaration that E is the tonal center, just as the E-flat chords that begin Beethoven’s Erioca are, among other things, a declaration that this is going to be a symphony in E-flat major. The task of the next hour’s music is to affirm that tonal center.1 As Robert Simpson so aptly puts it in his beautiful study The Essence of Bruckner, this “entrance. . . leads to a very lofty and light interior,” a vastly arching melody in which the cellos are subtly supported, now by a horn, now by the violas, now by a clarinet. To the extent that Bruckner conveys the feeling of an immense arch, he is giving us in microcosm the sense of the entire movement, with its grand pull away from the opening E major into the regions of B minor and B major, and its sovereign re-conquest of the original tonality. This is the first of three vividly contrasted themes, and it expands to become a paragraph of immense breadth. The second theme is slower and calmer. The melody rises, embellished by a graceful turn in its first phrase, but it is full of hesitations that make it sound touchingly vulnerable. Against soft bass chords, oboe and clarinet set it on its course. This too fills space grandly, and Bruckner does not fail to show us how beautiful the melody is when it is inverted. The music swells to an assertive fortissimo on suspenseful harmonies. What emerges from here is a theme, unharmonized and gray, that dances in a mysterious pianissimo. It gathers momentum and volume, arrives at a series of taut and loud brass chords like those that introduced it, then falls back into a suspenseful hush. Thus the development begins in darkness. Its journey is varied, with a range from densely active paragraphs to wonderful moments in contemplative stasis. The entrance into the recapitulation is sly, a serious counterpart to those unexpected, seemingly unprepared slippings into the home key that Haydn was so good at in humorous contexts. The coda, as almost always in Bruckner, is extraordinary. Its fifty-three measures are set over an unchanging E in the bass. For almost half of them, bass and superstructure are quietly at odds; then suddenly the orchestra gets the point, and the last thirty-one measures expand the bass-note upward into the great E-major affirmation we have been waiting for. Until the solemn Adagio actually begins, we do not even notice that Bruckner has so far stayed away from one of the most obvious harmonies a movement in E major would naturally travele This is Bruckner’s procedure in all his symphonies up to the Seventh and again in the unfinished Ninth. In the Eighth, however, he plays a different game, approaching his tonal center, C, obliquely and withholding unambiguous affirmation of it as long as possible. 1 toward, that of its relative minor, C sharp.2 With this harmony that is at once so close and so new, he introduces a new sound, that of a quartet of Wagner tubas, an instrument designed by Wagner for Der Ring des Nibelungen and intended to combine the mellowness of French howns with something of the weight of tuba tone. Here there is, however, a deeper association with Wagner. In January 1883 Bruckner wrote to the conductor Felix Mottl: “One day I came home and felt very sad. The though had crossed my mind that before long the Master would die, and just then the C-sharp-minor theme of the Adagio can to me.” Wagner did in fact die on 13 February, and the quiet closing music that begins with the quartet of Wagner tubas plus contrabass tuba became Bruckner’s memorial to the man he worshipped above all living musicians. What would one not give to have been present when, at one of his improvisations at Saint Florian’s, Bruckner wove together his own Adagio with the music for Siegfried’s funeral?3 Taking the slow movement of Beethoven’s Ninth as a model, Bruckner builds his Adagio on two contrasting ideas, the initial solemn one in minor, in 4/4 time, and a more pastoral, Schubertian one in major and in triple meter. The second of these is abandoned after two statements, both scored with striking richness and loveliness. What the strings play immediately after the movement begins, a firm sequence of rising steps, is an allusion to Bruckner’s own Te Deum, his last large-scale choral work, in progress at the same time as the Seventh Symphony and completed in March 1884. The words at that point of the Te Deum are “non confundar in aeternum” (let me not be confounded for ever), and Bruckner uses the momentum of those upwards steps to build a great climax in the first variation. Later he achieves another, one as stupendous as we can find in any symphony, and reached at a place—C major—almost unimaginably far from the harmonic origins of the movement. From that summit the music descends into the grief-stricken, then profoundly peaceful, threnody for Wagner. In most performances, the thrilling arrival at the great C-major climax in the Adagio is marked by a clash of cymbals with a roll of drums and triangle. This has been controversial almost from the beginning. It is clear that the cymbals and triangle were an afterthought of Bruckner’s, for their entry appears on an insert to the autograph score. To this insert Bruckner added six questions marks! These have been crossed out and the words “gilt night” (not valid) added above the measure in question; not all scholars, however, are convinced that this notation is in Bruckner’s hand. From a letter written by Josef Schalk to his brother Franz, we know that the cymbal clash in the Adagio of the Seventh was their idea and that the twenty-nine-year-old Arthur Mikisch, who conducted the premiere, talked Bruckner into accepting it—“which delights us wildly.” The structurally similar climax of the Adagio of the Symphony No. 8 has two cymbal clashes of undisputed authenticity; citing this parallel case, some measure of doubt about who added the “gilt nicht,” and the undeniable effectiveness of this spectacular punctuation, most conductors use the cymbals and triangle in the Seventh. 2 The relative minor is that minor key whose scale uses the same notes as that of its relative major. In general, when two keys share a large number of notes we speak of them as closely related; conversely, when two keys share relatively few notes we speak of them as distant or remote. The more distant two keys are, the more striking, or dramatic, or out-and-out startling, a shift from one to the other is likely to be. Sometimes, as in the is transition from the first movement to the second, a composer can, paradoxically, make a closely related key fell like fresh territory. 3 The concert at which Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7 had its premiere was a benefit to raise funds for a Wagner monument. The third movement is a Scherzo dominated by the restless ostinato of strings and the cheerily trumpeting cock-crow with which it begins. As is Bruckner’s custom, the Trio is somewhat slower, lightly scored, and pastoral in character. One of the features that define its pastoral nature is the prevalence of bagpipe-like long-held notes in the bass much as one might find them in musette movements in Baroque music. The Finale, to quote Simpson again, “blends solemnity and humor in festive grandeur.” It presents highly diversified ideas that run the gamut from the capricious and even the magnificently grotesque to the sublimely simple. At the end, all is gathered into a blaze of E major as we hear intimations of the symphony’s beginning and as the heavens open. © Michael Steinberg