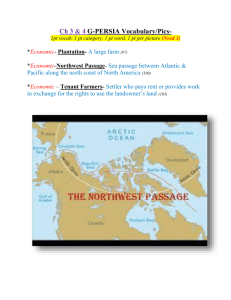

KS Blaber Zhao v SWS Brooks Horn R1

advertisement

Red and Black K The only ethical demand available to modern politics is that of the Slave and the Savage, the demand for the end of America itself. This demand exposes the grammar of the Affirmative for larger institutional access as a fortification of antiblack civil society Wilderson 07- [Frank B. Wilderson, Assistant professor of African American Studies and Drama at UC Irvine, Red, White, & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms, 5-7] When I was a young student at Columbia University in New York there was a Black woman who used to stand outside the gate and yell at Whites, Latinos, and East- and South Asian students, staff, and faculty as they entered the university. She accused them of having stolen her sofa and of selling her into slavery. She always winked at the Blacks, though we didn’t wink back. Some of us thought her outbursts too bigoted and out of step with the burgeoning ethos of multiculturalism and “rainbow coalitions” to endorse. But others did not wink back because we were too fearful of the possibility that her isolation would become our isolation, and we had come to Columbia for the express, though largely assumed and unspoken, purpose of foreclosing upon that peril. Besides, people said she was crazy. Later, when I attended UC Berkeley, I saw a Native American man sitting on the sidewalk of Telegraph Avenue. On the ground in front of him was an upside down hat and a sign informing pedestrians that here was where they could settle the “Land Lease Accounts” that they had neglected to settle all of their lives. He too, so went the scuttlebutt, was “crazy.” Leaving aside for the moment their state of mind, it would seem that the structure, that is to say the rebar, or better still the grammar of their demands— and, by extension, the grammar of their suffering—was indeed an ethical grammar. Perhaps their grammars are the only ethical grammars available to modern politics and modernity writ large, for they draw our attention not to the way in which space and time are used and abused by enfranchised and violently powerful interests, but to the violence that underwrites the modern world’s capacity to think, act, and exist spatially and temporally. The violence that robbed her of her body and him of his land provided the stage upon which other violent and consensual dramas could be enacted. Thus, they would have to be crazy, crazy enough to call not merely the actions of the world to account but to call the world itself to account, and to account for them no less! The woman at Columbia was not demanding to be a participant in an unethical network of distribution: she was not demanding a place within capital, a piece of the pie (the demand for her sofa notwithstanding). Rather, she was articulating a triangulation between, on the one hand, the loss of her body, the very dereliction of her corporeal integrity, what Hortense Spillers charts as the transition from being a being to becoming a “being for the captor” (206), the drama of value (the stage upon which surplus value is extracted from labor power through commodity production and sale); and on the other, the corporeal integrity that, once ripped from her body, fortified and extended the corporeal integrity of everyone else on the street. She gave birth to the commodity and to the Human, yet she had neither subjectivity nor a sofa to show for it. In her eyes, the world—and not its myriad discriminatory practices, but the world itself—was unethical. And yet, the world passes by her without the slightest inclination to stop and disabuse her of her claim. Instead, it calls her “crazy.” And to what does the world attribute the Native American man’s insanity? “He’s crazy if he thinks he’s getting any money out of us?” Surely, that doesn’t make him crazy. Rather it is simply an indication that he does not have a big enough gun. What are we to make of a world that responds to the most lucid enunciation of ethics with violence? What are the foundational questions of the ethico-political? Why are these questions so scandalous that they are rarely posed politically, intellectually, and cinematically—unless they are posed obliquely and unconsciously, as if by accident? Return Turtle Island to the “Savage.” Repair the demolished subjectivity of the Slave. Two simple sentences, twelve simple words, and the structure of U.S. (and perhaps global) antagonisms would be dismantled. An “ethical modernity” would no longer sound like an oxymoron. From there we could busy ourselves with important conflicts that have been promoted to the level of antagonisms: class struggle, gender conflict, immigrants rights. When pared down to twelve words and two sentences, one cannot but wonder why questions that go to the heart of the ethico-political, questions of political ontology, are so unspeakable in intellectual meditations, political broadsides, and even socially and politically engaged feature films. The 1AC’s celebration of native culture is politics of culture that affirms the human rather than a politics of culture. This celebration positions the savage in correspondence with the human which perpetuates antiblackness. Wilderson in 10 (Frank B. Wilderson, professor of Drama and African American studies @ University of California, Irvine, February 26, 2010, NB) Where in all of this is the Indian? The "Savage" has been glaringly absent in my preceding meditations on the Master and the Slave, for the same reason that Asians and Latinos are omitted from my study alto- gether. Latinos and Asians stand in conflictual relation to the Settler/ Master, that is, to the hemisphere and the United States writ large— they invoke a politics of culture, not a culture of politics. They do not register as antagonists. But this is only partially true of "Savage" position. Granted, the "Savage" relation to the Settler by way of libidinal economy's structure of exchange is far from isomorphic, at the level 31 of content, what Fanon calls "existence." For example, there is indeed Here important and resounding dissonance between the Indians spiritual or divine imagining of the subject in libidinal economy and the Settler/ Master's secular, or psychoanalytic, or even religious imaginings. But these differences do not cancel each other out. That is, they are not dif- ferences with an antagonistic structure, but differences with a conflictual structure, because articulation, rather than a void, makes the differences legible. In other words, "Savage" capacity is not obliterated by these differences. In fact, its interlocutory life is often fortified and extended by such differences. The modern or postmodern subject alienated in lan- guage, on the one hand, and the Great Spirit devotee, or child of Mother Earth, on the other, may in fact be elaborated by different cosmologies, predicated on what Vine Deloria Jr. has noted as conflictual visions, but Lacans analysand (meaning a subjective capacity for full or empty speech) does not require the Indian as its parasitic host, despite the Indians forcible removal to clear a space for the analyst's office. This is because alienation is essential to both the "Savage" and the Settler's way of imag- ining structural positionality, to the 32 33 way Native American metacommen- taries think ontology. Thus, the analysand's essential capacity for alien- ation from being (alienation that takes place in language) is not parasitic on the "Savage's" capacity to be alienated from the spirit world or the land (which for Indians are cosmologically inseparable). Whereas historically, the secular imperialism which made psychoanalytic imaginings possible wreaked havoc on the "Savage" at the level of Fanonian existence, that con- tact did not wipe out his or her libidinal capacity—or Native metaphysics. This is true not in some empirical sense, for as a Black I have no access to the Indian's spirit world. I am also barred from subjectivity in even the most revolutionary schemata of White secularism (Lacanian psychoanal- ysis and Negri's Marxism). Rather, it is true because the most profound and unflinching metacommentators on the "Savage" and libidinal econ- omy (although Indians would probably replace "libidinal economy" with "spirit world" and "the subject" with "the soul") and the most unflinching metacommentators on the Settler and libidinal economy say it is true. Having communed around their shared capacity for subjective alienation since the dawn of modernity (what Indians call "contact"), they formed a community of interpretation. Even as Settlers began to wipe Indians out, they were building an interpretive community with "Savages" the likes of which Masters were not building with Slaves. The AFFs politics of inclusion is structural adjustment of the black body that forecloses black liberation. If we win their scholarship produces this structural violence that is a reason to vote negative Wilderson 2010- Frank B Wilderson III- Professor at UC irvine- Red, White and Blackp. 8-10 I have little interest in assailing political conservatives. Nor is my ar- gument wedded to the disciplinary needs of political science, or even sociology, where injury must be established, first, as White supremacist event, from which one then embarks on a demonstration of intent, or racism; and, if one is lucky, or foolish, enough, a solution is proposed. If the position of the Black is, as I argue, a paradigmatic impossibility in the Western Hemisphere, indeed, in the world, in other words, if a Black is the very antithesis of a Human subject, as imagined by Marxism and psy- choanalysis, then his or her paradigmatic exile is not simply a function of repressive practices on the part of institutions (as political science and sociology would have it). This banishment from the Human fold is to be found most profoundly in the emancipatory meditations of Black people's staunchest "allies," and in some of the most "radical" films. Here— not in restrictive policy, unjust legislation, police brutality, or conservative scholarship—is where the Settler/Master's sinews are most resilient. The polemic animating this research stems from (1) my reading of Native and Black American meta-commentaries on Indian and Black subject positions written over the past twenty-three years and ( 2 ) a sense of how much that work appears out of joint with intellectual protocols and political ethics which underwrite political praxis and socially engaged popular cinema in this epoch of multiculturalism and globalization. The sense of abandonment I experience when I read the meta-commentaries on Red positionality (by theorists such as Leslie Silko, Ward Churchill, Taiaiake Alfred, Vine Deloria Jr., and Haunani-Kay Trask) and the meta-commentaries on Black positionality (by theorists such as David Marriott, Saidiya Hartman, Ronald Judy, Hortense Spillers, Orlando Patterson, and Achille Mbembe) against the deluge of multicultural positivity is overwhelming. One suddenly realizes that, though the semantic field on which subjec- tivity is imagined has expanded phenomenally through the protocols of multiculturalism and globalization theory, Blackness and an unflinching articulation of Redness are more unimaginable and illegible within this expanded semantic field than they were during the height of the F B I ' S repressive Counterintelligence Program ( C O I N T E L P R O ) . On the seman- tic field on which the new protocols are possible, Indigenism can indeed lO become partially legible through a programmatics of structural adjust- ment (as fits our globalized era). In other words, for the Indians' subject position to be legible, their positive registers of lost or threatened cultural identity must be foregrounded, when in point of fact the antagonistic register of dispossession that Indians "possess" is a position in relation to a socius structured by genocide. As Churchill points out, everyone from Armenians to Jews have been subjected to genocide, but the Indigenous position is one for which genocide is a constitutive element, not merely an historical event, without which Indians would not, paradoxically, "exist." 9 Regarding the Black position, some might ask why, after claims suc- cessfully made on the state by the Civil Rights Movement, do I insist on positing an operational analytic for cinema, film studies, and political theory that appears to be a dichotomous and essentialist pairing of Masters and Slaves? In other words, why should we think of today's Blacks in the United States as Slaves and everyone else (with the exception of Indians) as Masters? One could answer these questions by demonstrat- ing how nothing remotely approaching claims successfully made on the state has come to pass. In other words, the election of a Black president aside, police brutality, mass incarceration, segregated and substandard schools and housing, astronomical rates of H I V infection, and the threat of being turned away en masse at the polls still constitute the lived expe- rience of Black life. But such empirically based rejoinders would lead us in the wrong direction; we would find ourselves on "solid" ground, which would only mystify, rather than clarify, the question. We would be forced to appeal to "facts," the "historical record," and empirical markers of stasis and change, all of which could be turned on their head with more of the same. Underlying such a downward spiral into sociology, political sci- ence, history, and public policy debates would be the very rubric that I am calling into question: the grammar of suffering known as exploitation and alienation, the assumptive logic whereby subjective dispossession is arrived at in the calculations between those who sell labor power and those who acquire it. The Black qua the worker. Orlando Patterson has already dispelled this faulty ontological grammar in Slavery and Social Death, where he demonstrates how and why work, or forced labor, is not a constituent element of slavery. Once the "solid" plank of "work" is removed from slavery, then the conceptually coherent notion of "claims against the state"—the proposition that the state and civil society are elastic enough to even contemplate the possibility of an emancipatory project for the Black position—disintegrates into thin air. The imaginary of the state and civil society is parasitic on the Middle Passage. Put an- other way, No slave, no world. And, in addition, as Patterson argues, no slave is in the world. If, as an ontological position, that is, as a grammar of suffering, the Slave is not a laborer but an anti-Human, a position against which Hu- manity establishes, maintains, and renews its coherence, its corporeal in- tegrity; if the Slave is, to borrow from Patterson, generally dishonored, perpetually open to gratuitous violence, and void of kinship structure, that is, having no relations that need be recognized, a being outside of re- lationality, then our analysis cannot be approached through the rubric of gains or reversals in struggles with the state and civil society, not unless and until the interlocutor first explains how the Slave is of the world. The onus is not on one who posits the Master/Slave dichotomy but on the one who argues there is a distinction between Slaveness and Blackness. How, when, and where did such a split occur? The woman at the gates of Columbia University awaits an answer. Strategies for curtailing/modifying surveillance fail to question the state itself, this allows the state to continue violent surveillance techniques that render native populations manageable and expendable Smith 15’ (Andrea Smith “NOT-SEEING: State Surveillance, Settler Colonialism, and Gender Violence,” Dubrofsky, Rachel E. Feminist Surveillance Studies. N.p.: Duke UP, 2015. Pgs 21-38. KLB) The focus of surveillance studies has generally been on the modern, bureaucratic state. And yet, as David Stannard's (1992) account of the sexual surveillance of indigenous peoples within the Spanish mission system in the Americas demonstrates, the history of patriarchal and colonialist surveillance in this continent is much longer. The traditional account of surveillance studies tends to occlude the manner in which the settler state is foundationally built on surveillance. Because surveillance studies focuses on the modern, bureaucratic state, it has failed to account for the gendered colonial history of surveillance. Consequently, the strategies for addressing surveillance do not question the state itself, but rather seek to modify the extent to which and the manner in which the state surveils. As Mark Rifkin (2011) and Scott Morgensen (2011) additionally demonstrate, the sexual surveillance of native peoples was a key strategy by which native peoples were rendered manageable populations within the colonial state. One would think that an anticolonial feminist analysis would be central to the field of surveillance studies. Yet, ironically , it is this focus on the modern state that often obfuscates the settler colonialist underpinning of technologies of surveillance. I explore how a feminist surveillance-studies focus on gendered colonial violence reshapes the field by bringing into view that which cannot be seen: the surveillance strategies that have effected indigenous disappearance in order to establish the settler state itself. In particular, a focus on gendered settler colonialism foregrounds how surveillance is not simply about "seeing" but about "not-seeing" the settler state. The granting of freedom from surveillance to the native by the 1AC perpetuates settler colonialism which pushes native people into social death and extends settler colonialism into the future Byrd 2011 [Jodi Associate Professor of English, American Indian Studies, and Gender and Women’s Studies at U of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism (First Peoples: New Directions Indigenous)]-DD But what seems to me to be further disavowed, even in Lowe’s important figuration of the history of labor in “the intimacies of four continents,” is the settler colonialism that such labor underwrites. Asia, Africa, and Europe all meet in the Americas to labor over the dialectics of free and unfree , but what of the Americas themselves and the prior peoples upon whom that labor took place ? Lowe includes “native peoples” in her figurations as an addendum when she writes that she hopes “to evoke the political economic logics through which men and women from Africa and Asia were forcibly transported to the Americas, who with native, mixed, and creole peoples constituted slave societies, the profits of which gave rise to bourgeois republican states in Europe and North America.” 23 By positioning the conditions of slavery and indentureship in the Americas as coeval contradictions through which Western freedom affirms and resolves itself, and then by collapsing the indigenous Americas into slavery, the fourth continent of settler colonialism through which such intimacy is made to labor is not just forgotten or elided; it becomes the very ground through which the other three continents struggle intimately for freedom, justice, and equality. Within Lowe’s formulation, the native peoples of the Americas are collapsed into slavery; their only role within the disavowed intimacies of racialization is either one equivalent to that of African slaves or their ability to die so imported labor can make use of their lands. Thus, within the “intimacies of four continents,” indigenous peoples in the new world cannot, in this system, give rise to any historical agency or status within the “economy of affirmation and forgetting,” because they are the transit through which the dialectic of subject and object occurs. Byrd, Jodi A. (2011-09-06). Colonialism is the root cause of surveilance Zureik, professor of sociology at Queens University, CA, 2013 (Elia Zureik, “Colonial Oversight”, Oct/Nov 2013, http://www.sscqueens.org/sites/default/files/Zureik%20Colonial%20oversight%20essay %20Red%20Pepper%20octnov13-1-1.pdf)CQF In their book Post-Colonial Studies: The Key Concepts, Ashcroft, Griffiths and Tiffin observe that: ‘ One of the most powerful strategies of imperial dominance is that of surveillance, or observation, because it implies a viewer with an elevated vantage point, it suggests the power to process and understand that which is seen, and it objectifies and interpellates the colonised subject in a way that fixes its identity in relation to the surveyor.’ One can safely argue that colonialism and imperialism provided the impetus for developing modern surveillance technologies. In the name of state security, surveillance emerged as essential for managing the population and territory. This occurred in the quotidian everyday context of people watching people. It was also a formal aspect of colonial policies whereby surveillance was embodied in bureaucratic, enumerative and legal measures that aimed to control the territory and classify the population, a pattern that some researchers call ‘panopticism’. Edward Said expressed it succinctly when he described quantification and categorisation as discursive forms of surveillance. ‘To divide, deploy,s schematise, tabulate, index, and record everything in sight (and out of sight – in original),’ he argued, ‘are the features of Orientalist projections.’ In C A Bayly’s masterful book Empire and Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India 1780–1870, he shows how the gathering of information in pre- and post-colonial India involved not only census and survey data about the population and territory but information gathered through informal surveillance by astrologers, physicians, marriage brokers and holy men. The categorisation and enumeration of the population in pre-colonial India was carried out by local elites, and subsequently modified and implemented by the Colonial oversight As they colonised the world, European governments invented techniques for tracking the people they conquered. ELIA ZUREIK reveals how domestic spying has roots in imperial history 47 British for the purpose of ruling and taxation. From the mid-18th century onwards the British cultivated ‘colonial knowledge’, embedded in a corpus of Orientalist trope. Although stereotyping of the Other is a basic staple of colonialism, Bayly rightly points out, it is not always successful and triggers resistance by the colonised. The resistance to British rule in India shows how the colonised successfully used the same tools of information dissemination that were applied by the British to control them, notably the print media. In considering her work on India, ‘Panopticon in Poona: An Essay on Foucault and Colonialism’, Martha Kaplan remarks: ‘Clearly, the power of colonised people to articulate their own projects, to challenge colonial discourses and to make their own histories constrains the projects of colonisers and – sometimes – remakes the panopticon into a constraint on its constructors.’ The alternative is a program of complete disorder that begins and ends with the Slave’s demand to end the world. This is the starting point of decolonization. Wilderson 02 [Frank Wilderson, gotcha, 2002, “The Prison Slave as Hegemony's (Silent) Scandal”] Civil society is not a terrain intended for the Black subject. It is coded as waged and wages are White. Civil society is the terrain where hegemony is produced, contested, mapped. And the invitation to participate in hegemony's gestures of influence, leadership, and consent is not extended to the unwaged. We live in the world, but exist outside of civil society. This structurally impossible position is a paradox, because the Black subject, the slave, is vital to political economy: s/he kick-starts capital at its genesis and rescues it from its overaccumulation crisis at its end. But Marxism has no account of this phenomenal birth and life-saving role played by the Black subject: from Marx and Gramsci we have consistent silence. In taking Foucault to task for assuming a universal subject in revolt against discipline, in the same spirit in which I have taken Gramsci to task for assuming a universal subject, the subject of civil society in revolt against capital, Joy James writes: The U.S. carceral network kills, however, and in its prisons, it kills more blacks than any other ethnic group. American prisons constitute an "outside" in U.S. political life. In fact, our society displays waves of concentric outside circles with increasing distances from bourgeois self-policing. The state routinely polices the14 unassimilable in the hell of lockdown, deprivation tanks, control units , and holes for political prisoners (Resisting State Violence 1996: 34 ) But this peculiar preoccupation is not Gramsci's bailiwick. His concern is with White folks; or with folks in a White(ned) enough subject position that they are confronted by, or threatened by the removal of, a wage -be it monetary or social. But Black subjectivity itself disarticulates the Gramscian dream as a ubiquitous emancipatory strategy, because Gramsci, like most White activists, and radical American movements like the prison abolition movement, has no theory of the unwaged, no solidarity with the slave. If we are to take Fanon at his word when he writes, “Decolonization, which sets out to change the order of the world, is, obviously, a program of complete disorder“ (37) then we must accept the fact that no other body functions in the Imaginary, the Symbolic, or the Real so completely as a repository of complete disorder as the Black body. Blackness is the site of absolute dereliction at the level of the Real, for in its magnetizing of bullets the Black body functions as the map of gratuitous violence through which civil society is possible: namely, those other bodies for which violence is, or can be, contingent. Blackness is the site of absolute dereliction at the level of the Symbolic, for Blackness in America generates no categories for the chromosome of History, no data for the categories of Immigration or Sovereignty; it is an experience without analog “a past, without a heritage. Blackness is the site of absolute dereliction at the level of the Imaginary for “whoever says “rape “ says Black, “ (Fanon) , whoever says “prison “ says Black, and whoever says “AIDS “ says Black (Sexton), the “Negro is a phobogenic object “ (Fanon). Indeed, a phobogenic object, a past without a heritage, the map of gratuitous violence, a program of complete disorder. But whereas this realization is, and should be cause for alarm, it should not be cause for lament, or worse, disavowal “ not at least, for a true revolutionary, or for a truly revolutionary movement such as prison abolition. 15 If a social movement is to be neither social democratic, nor Marxist, in terms of the structure of its political desire then it should grasp the invitation to assume the positionality of subjects of social death that present themselves; and, if we are to be honest with ourselves we must admit that the “Negro “ has been inviting Whites, and as well as civil society’s junior partners, to the dance of social death for hundreds of years, but few have wanted to learn the steps. They have been, and remain today “even in the most anti-racist movements, like the prison abolition movement “ invested elsewhere. This is not to say that all oppositional political desire today is pro-White, but it is to say that it is almost always “anti-Black” which is to say it will not dance with death. Black liberation, as a prospect, makes radicalism more dangerous to the U.S. not because it raises the specter of some alternative polity (like socialism, or community control of existing resources) but because its condition of possibility as well as its gesture of resistance functions as a negative dialectic: a politics of refusal and a refusal to affirm, a program of complete disorder. One must embrace its disorder, its incoherence and allow oneself to be elaborated by it, if indeed one's politics are to be underwritten by a desire to take this country down. If this is not the desire which underwrites one’s politics then through what strategy of legitimation is the word “prison “ being linked to the word “abolition“? What are this movement’s lines of political accountability? There’s nothing foreign, frightening, or even unpracticed about the embrace of disorder and incoherence. The desire to be embraced, and elaborated, by disorder and incoherence is not anathema in and of itself: no one, for example, has ever been known to say “gee-whiz, if only my orgasms would end a little sooner, or maybe not come at all. “ But few so-called radicals desire to be embraced, and elaborated, by the disorder and incoherence of Blackness “and the state of political movements in America today is marked by this very Negrophobogenisis: “gee-whiz, if only Black rage could be more coherent, or maybe not come at all. “ Perhaps there“s something more terrifying about the joy of Black, then there is about the joy of sex (unless one is talking sex with a Negro). Perhaps coalitions today prefer to remain in- orgasmic in the face of civil society “with hegemony as a handy prophylactic, just in case. But if, through this stasis, or paralysis , they try to do the work of prison abolition“ that work will fail; because it is always work from a position of coherence (i.e. the worker) on behalf of a position of incoherence, the Black subject, or prison slave. In this way, social formations on the Left remain blind to the contradictions of coalitions between workers and slaves. They remain coalitions operating within the logic of civil society; and function less as revolutionary promises and more as crowding out scenarios of Black antagonisms “they simply feed our frustration. Whereas the positionality of the worker “ be s/he a factory worker demanding a monetary wage or an immigrant or White woman demanding a social wage “ gestures toward the reconfiguration of civil society, the positionality of the Black subject “be s/he a prison-slave or a prisonslave-in-waiting“ gestures toward the disconfiguration of civil society: from the coherence of civil society, the Black subject beckons with the incoherence of civil war. A civil war which reclaims Blackness not as a positive value, but as a politically enabling site, to quote Fanon, of “absolute dereliction“: a scandal which rends civil society asunder. Civil war, then, becomes that unthought, but never forgotten understudy of hegemony. A Black specter waiting in the wings, an endless antagonism that cannot be satisfied (via reform or reparation) but must nonetheless be pursued to the death. The alternative is always already a decolonial struggle - we must begin at anti-blackness in order to disrupt the settler state which perpetuates native genocide Smith 14 [Andrea Smith, Prof. Media and Cultural Studies @ UC-Riverside, intellectual, feminist, anti-violence activist, co-founder of INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence, 2014, “The Colonialism That is Settled and the Colonialism That Never Happened,” https://decolonization.wordpress.com/2014/06/20/the-colonialism-that-is-settled-andthe-colonialism-that-never-happened/ Because Africa is deemed the property of Europe, Africa must then appear as always, already colonized. Native studies is often articulated as concerned being primarily with colonization (and, subsequently, decolonization) while Black studies is articulated as concerned primarily with race (and, subsequently, anti-racism). However, this distinction is itself a product of anti-Blacknesss. The colonization of Africa must disappear so that Africa can appear as ontologically colonized. According to Justice Daniel, since only “nations” can be colonized, nations in African can never have existed. It is only through the disavowal of colonization that Black peoples can be ontologically relegated to the status of property. Within the Dred Scott decision, Native peoples by contrast, are situated as potential citizens. Native peoples are described as “free” people, albeit “uncivilized.” While because of their child-like primitive state, they are not worthy of citizenship at the moment, they may eventually become citizens if they were to renounce their relationship to their Native nation and demonstrate the “maturity” required to become a citizen. Native peoples can claim a certain kind of nation; however, it is nation that must disappear. Thus, Native peoples’ apparent proximity to whiteness should not be understood as a pathway to freedom but as a pathway to genocide. Indigenous nations are supposed to disappear into whiteness (or, to borrow from Maile Arvin, to be possessed by whiteness) in order to effectuate their genocide. As Robert Nichols notes in his essay in Theorizing Native Studies, settler colonialism sets the very terms of its contestation. And the terms of contestation set by settler colonialism is anti-racism. That is, the way we are supposed to contest settler democracy is to contest the gap between what settler democracy promises and what it performs. But as Nichols notes, contesting the racial gap of setter democracy is the most effective way of actually ensuring its universality. Thus, borrowing from this analysis, settler colonialism does not merely operate by racializing Native peoples, positioning them as racial minorities rather than as colonized nations, but also through domesticating Black struggle within the framework of anti-racist rather than anti-colonial struggle. AntiBlackness is effectuated through the disappearance of colonialism in order to render Black peoples as the internal property of the United States, such that anti-Black struggle must be contained within a domesticated anti-racist framework that cannot challenge the settler state itself. Why, for example, is Martin Luther King always described as a civil rights leader rather than an anti-colonial organizer, despite his clear anti-colonial organizing against the war in Vietnam? Through anti-Blackness, not only are Black peoples rendered the property of the settler state, but Black struggle itself remains its property – solely containable within the confines of the settler state. Thus, the colonialism that never happened – antiBlackness – helps reinforce the colonialism that is settled – the genocide of Indigenous peoples. For the so-called ‘Indian problem’ to disappear, the United States must itself appear hermetically sealed from both internal and external threats that would threaten its legitimacy and continued existence. Indigenous peoples must be made to disappear as internal threats, made to exist in a constant state of vanishing, in no position to unsettle the settler state. Meanwhile the external threat posed by a global Black anticolonial struggle is made to disappear by rendering Africa as the property of the United States and, subsequently, no longer external to it. Anti-Blackness, then, is not only constitutive of the settler nation of the United States, but integral to the normalization of its continuance. Case Indigenous peoples become epistemological possessions under the 1AC’s framework, through the same root mentality of subjugation and subordination, and are devalued only to what their knowledge can do for whitewashed academia. Fredericks in 09 (Bronwyn, Professor Bronwyn Fredericks, Pro Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Engagement) and BMA Chair in Indigenous Engagement leads the work undertaken by the Office of Indigenous Engagement & holds a Diploma of Teaching (Secondary), Bachelor of Education, Master of Education – Leadership & Management, Master of Education Studies and a PhD (Health Science) @ CQU University, THE EPISTEMOLOGY THAT MAINTAINS WHITE RACE PRIVILEGE, POWER AND CONTROL OF INDIGENOUS STUDIES AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ PARTICIPATION IN UNIVERSITIES, p.4-6, 11/26/14, NB) Within this university, non-Indigenous people are remunerated to talk about Indigenous peoples, cultures, knowledges and histories and to gauge how much knowledge and understanding others will gain about Indigenous people. As such they hold what is considered “legitimate knowledge” that underpins and maintains their power within the university (Alfred 2004; Henderson 2000; Martin 2003; Smith 1999). The people that clearly owned Indigenous Studies within this university were non-Indigenous people. As will be demonstrated, the processes of the review and the terms in which Pamela and I were invited to participate excluded us from holding any a further investment in the white possession of Indigenous Studies in that university. Had I participated in the review under the conditions set down for me, it would have maintained the discrepancies of power and control between the paid non-Indigenous employees on the panel who talk about, write about and who are given authority to control information within the university about Indigenous people, and the authentic Indigenous voices of Indigenous women who were offered no value other than what Marcelle Gareau (2003: 197) calls a “targeted resource” and Shahnaz Khan form of ownership, even temporarily, and would lead to what Aileen Moreton-Robinson (2005b) would describe as (2005: 2025) terms a “native informant”. We would be undertaking this position in order to legitimate the academic processes This amounts to a recycling of the colonial power gained through colonisation and a distinct difference between those with institutional privilege and those without. Indigenous Studies and Indigenous people are objectified and reproduced as objects within this context and are what Moreton-Robinson (2008) would term “epistemological possessions” of the non-Indigenous people involved in the review and by this university. I also noted that what was spoken of, as a form of gift or thanks by the contact person, was food, which of non-Indigenous people. in fact resonated as a reminder of the past as if food rations were being offered from the coloniser to the colonised (Rintoul my participation without payment would have affirmed “white domination and economic success at the cost of racial and economic oppression” (Moreton-Robinson 2005b: 26). 1993). In short, Through my telephone discussion with the university-based academic who had originally contacted me, and on critical I knew that Pamela and I were being expected to give our knowledge, skills and abilities in Indigenous Studies for “our people” based on “goodwill”, “community service“ and for “white people who wanted to learn about us”. The university staff involved had based our possible reflection, participation on their epistemiological framework of us as Indigenous women with doctoral postgraduate qualifications (Croft 2003; Fredericks 2003). Our possible participation was constructed through our Indigenous embodiment as racial and gendered objects and based on their desire for us to be the Indigenous “Other”, albeit with doctoral qualifications: the symbols of attainment and credentials of the academy. We were defined as both subject and object through our Aboriginality and offered a positioning of subjugation and subordination. From the review team’s perspective this is what would add value to the review and provide legitimacy and advantage to the university and the non-Indigenous people. The non-Indigenous people were positioned as the experts and knowers and offered the on-going positioning of authority, legitimacy, domination and control. We were being asked to perform the role of female Indigenous academics who would be used to service the non-Indigenous academics in the same way that Indigenous people were required to service non-Indigenous people in colonial history (Huggins 1989; Rintoul 1993). As explained by Moreton- Robinson (2008: 86), placing us in such a service relationship also positions our Aboriginality “as an epistemological possession to service what it is not” and to“obscure the more complex way that white possession functions socio- discursively through subjectivity and knowledge production”. It also diverts our attention from our own and community priorities to the priorities of the dominant society. The situation represented a form of identity politics that is rooted in Australian colonial history and that has contributed to the ongoing historical, legal and political racialisation and marginalisation of Indigenous peoples. Their claim to “decolonize” debate curriculum posits decolonization as a metaphor; this is emblematic settler colonialism, functioning as a palliative for settler guilt and enabling moves to innocence that recenter whiteness and kill the possibility of the only true form of decolonization, OF LAND. Tuck and Yang in 14 (Eve, Associate Professor of Educational Foundations and Coordinator of Native American Studies @ State University of New York at New Paltz, and K. Wayne, Associate Professor in Ethnic Studies @ UC San Diego, “Decolonization is not a Metaphor”, p.2-4, 11/26/14, NB) For the past several years we have been working, in our writing and teaching, to bring attention to how settler colonialism has shaped schooling and educational research in the United States and other settler colonial nation-states. These are two distinct but overlapping tasks, the first concerned with how the invisibilized dynamics of settler colonialism mark the organization, governance, curricula, and assessment of compulsory learning, the other concerned with how settler perspectives and worldviews get to count as knowledge and research and how these perspectives - repackaged as data and findings - are activated in order to rationalize and maintain unfair social structures. We are doing this work alongside many others who - somewhat relentlessly, in writings, meetings, courses, and activism - don’t allow the real and symbolic violences of settler colonialism to be overlooked. Alongside this work, we have been thinking about what decolonization means, what it wants and requires. One trend we have noticed, with growing apprehension, is the ease with which the language of decolonization has been superficially adopted into education and other social sciences, supplanting prior ways of talking about social justice, critical methodologies, or approaches which decenter settler perspectives. Decolonization, which we assert is a distinct project from other civil and human rights-based social justice projects, is far too often subsumed into the directives of these projects, with no regard for how decolonization wants something different than those forms of justice. Settler scholars swap out prior civil and human rights based terms, seemingly to signal both an awareness of the significance of Indigenous and decolonizing theorizations of schooling and educational research, and to include Indigenous peoples on the list of considerations - as an additional special (ethnic) group or class. At a conference on educational research, it is not uncommon to hear speakers refer, almost casually, to the need to “decolonize our schools,” or use “decolonizing methods,” or “decolonize student thinking.” Yet, we have observed a startling number of these discussions make no mention of Indigenous peoples, our/their1 struggles for the recognition of our/their sovereignty, or the contributions of Indigenous intellectuals and activists to theories and frameworks of decolonization. Further, there is often little recognition given to the immediate context of settler colonialism on the North American lands where many of these conferences take place. Of course, dressing up in the language of decolonization is not as offensive as “Navajo print” underwear sold at a clothing chain store (Gaynor, 2012) and other appropriations of Indigenous cultures and materials that occur so frequently. Yet, this kind of inclusion is a form of enclosure, dangerous in how it domesticates decolonization. It is also a foreclosure, limiting in how it recapitulates dominant theories of social change. On the occasion of the inaugural issue of Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, & Society, we want to be sure to clarify that decolonization is not a metaphor. When metaphor invades decolonization, it kills the very possibility of decolonization; it recenters whiteness, it resettles theory, it extends innocence to the settler, it entertains a settler future. Decolonize (a verb) and decolonization (a noun) cannot easily be grafted onto pre-existing discourses/frameworks, even if they are critical, even if they are anti- The easy absorption, adoption, and transposing of decolonization is yet another form of settler appropriation. When we write about decolonization, we are not offering it as a metaphor; it is not an approximation of other experiences of oppression. Decolonization is not a swappable term for other things we want to do to improve our racist, even if they are justice frameworks. societies and schools. Decolonization doesn’t have a synonym. Our goal in this essay is to remind readers what is unsettling about decolonization - what is unsettling and what should be unsettling. Clearly, we are advocates for the analysis of settler colonialism within education and education research and we position the work of Indigenous thinkers as central in unlocking the confounding aspects of public schooling. We, at least in part, want others to join us in these efforts, so that settler colonial structuring and Indigenous critiques of that structuring are no longer rendered invisible. Yet, this joining cannot be too easy, too open, too settled. Solidarity is an uneasy, reserved, and unsettled matter that neither reconciles present grievances nor forecloses future conflict. There are parts of the decolonization project that are not easily absorbed by human rights or civil rights based approaches to educational equity. In this essay, we think about what decolonization wants. There is a long and bumbled history of non-Indigenous peoples making moves to alleviate the impacts of colonization. The too-easy adoption of decolonizing discourse (making decolonization a metaphor) is just one part of that history and it taps into pre-existing tropes that get in the way of more meaningful potential alliances. We think of the enactment of these tropes as a series of moves to innocence (Malwhinney, 1998), which problematically attempt to reconcile settler guilt and complicity, and rescue settler futurity. Here, to explain why decolonization is and requires more than a metaphor, we discuss some of these moves to innocence: i. Settler nativism ii. Fantasizing adoption iii. Colonial equivocation iv. Conscientization v. At risk-ing / Asterisk-ing Indigenous peoples vi. Re-occupation and urban homesteading Such moves ultimately represent settler fantasies of easier paths to reconciliation. Actually, we argue, attending to what is irreconcilable within settler colonial relations and what is incommensurable between decolonizing projects and other social justice projects will help to reduce the frustration of attempts at solidarity; but the attention won’t get anyone off the hook from the hard, unsettling work of decolonization. we also include a discussion of interruptions that unsettle innocence and recognize incommensurability. Thus, The Affirmatives attempt to eradicate evil is a politics of ressentiment which holds radical alternatives hostage in the name of attempts to heal the world – the impact is the perpetuation of symbolic capital which profits off our suffering Baudrillard ’05 [Intelligence of Evil, 144-45] Evil is the world as it is and has been, and we can take a lucid view of this. Misfortune is the world as it ought never to have been – but in the name of what? In the name of what ought to be, in the name of God or a transcendent ideal, of a good it would be very hard to define. We may take a criminal view of crime: that is tragedy. Or we may take a reciminative view of it: that is humanitarianism; it is the pathetic, sentimental vision, the vision that calls constantly for reparation. We have here all the Ressentiment that comes from the depths of a genealogy of morals and calls within us for reparation of our own lives. This retrospective compassion, this conversion of evil into misfortune, is the twentieth century’s finest industry. First as a mental blackmailing operation, to which we are all victim, even in our actions, from which we may hope only for a lesser evil – keep a low profile, decriminate your existence! – then as a source of a tidy profit, since misfortune (in all its forms, from suffering to insecurity, from oppression to depression) represents a symbolic capital, the exploitation of which, even more than the exploitation of happiness, is endlessly profitable: it is a goldmine with a seam running through each of us. Contrary to received opinion, misfortune is easier to manage than happiness – that is why it is the ideal solution to the problem of evil. It is misfortune that is Just as freedom ends in total liberation and, in abreaction to that liberation, in new servitudes, so the ideal of happiness leads to a whole culture of misfortune, of recrimination, repentance, compassion and victimhood. most distinctly opposed to evil and to the principle of evil, of which it is the denial .