PPT

advertisement

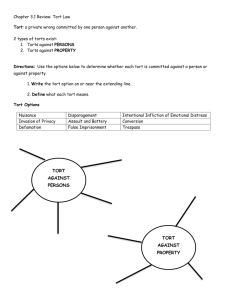

THE LAW OF TORTS Weekend School 1 TEXT BOOKS • Dominic Villa Annotated Civil Liability Act Lawbook Co. (2013) • Balkin and Davis The Law of Torts 5th Ed LexisNexis • Luntz & Hambly, Torts - Cases and Commentary, 7th ed. LexisNexis, • Stewart and Stuhmcke, Australian Principles of Torts Law Federation Press, 3rd Ed • Davies and Malkin, Torts LexisNexis 6th Ed • Blay, Torts in a Nutshell LBC INTRODUCTION WEEK 1 DEFINITION: THE NATURE OF TORTS WHAT IS A TORT? •A tort is a civil wrong •That (wrong) is based a breach of a duty imposed by law THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN A TORT AND A CRIME •A crime is a public /community wrong that gives rise to sanctions usually designated in a specified code. A tort is a civil ‘private’ wrong. • An action in criminal law is usually brought by the state or the Crown. Tort actions are usually brought by the victims of the tort. • The principal objective in criminal law is punishment. In torts, it is compensation THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A TORT AND A CRIME • Differences in Procedure: – Standard of Proof Criminal law: beyond reasonable doubt »Torts: on the balance of probabilities » TORTS and CRIME TORTS • A civil action • Brought by the victim • To provide a remedy • Remedy: compensation • Proof: balance of probabilities CRIME • A criminal action • Brought by the Crown • To punish the perpetrator • Remedy: punishment • Proof: beyond reasonable doubt SIMILARITIES BETWEEN TORTS AND CRIME •They both arise from wrongs imposed by law •Certain crimes are also actionable torts; eg trespass: assault •In some cases the damages in torts may be punitive •In some instances criminal law may award compensation under criminal injuries compensation legislation. TORTS DISTINGUISHED FROM BREACH OF CONTRACT •A breach of contract arises from breach of promise(s) made by the parties themselves. TORTS and CONTRACT • • • • • TORTS Duty owed generally Duty imposed by law promises or agreement Protects what is already owned or possessed Damages unliquidated • • • • CONTRACT Duty to other contracting party Duty arises from parties' Protects expectation of future benefits Damages often liquidated SIMILARITIES BETWEEN TORT AND CONTRACT •Both tort and breach of contract give rise to civil suits •In some instances, a breach of contract may also be a tort: eg an employer’s failure to provide safe working conditions THE OBJECTIVES OF TORT LAW •Loss distribution/adjustment: shifting losses from victims to perpetrators •Compensation: Through the award of (pecuniary) damages –The object of compensation is to place the victim in the position he/she was before the tort was committed. •Punishment: through exemplary or punitive damages. This is a secondary aim. INTEREST PROTECTED AND RELEVANT ACTIONS INTEREST • Personal Security TORT • Trespass, Negligence • Reputation • Property • Defamation • Trespass, Negligence, Conversion, Detinue • False Imprisonment • Nervous shock, Wilkinson v Downtown • Malicious prosecution • Negligence ( pure financial loss) • • • • Liberty Mental tranquility Abuse of legal process Financial Interest SOURCES OF TORT LAW •Common Law: – The development of torts by precedent through the courts » Donoghue v Stevenson •Statute: – Thematic statutes: eg Motor Accidents legislation » Motor Accidents Compensation Act 1999 – General statutes: eg Civil Liability legislation » The Civil Liability Act (NSW) 2002 LIABILITY IN TORT LAW • Liability = responsibility • Liability may be based on fault or it may be strict • Fault liability: the failure to live up to a standard through an act or omission . • Types of fault liability: FAULT LIABILITY NEGLIGENCE INTENTION Intention in Torts •Deliberate or wilful conduct • ‘Constructive’ intent: where the consequences of an act are substantially certain: the consequences are intended •Where conduct is reckless •Transferred intent: where D intends to hit ‘B’ but misses and hits ‘P’ Negligence in Torts •When D is careless in his/her conduct •When D fails to take reasonable care to avoid a reasonably foreseeable injury to another and that party suffers damage. STRICT LIABILITY •No fault is required for strict liability ACTIONS IN TORT LAW • Trespass –Directly caused injuries –Requires no proof of damage ( actionable per se) •Action on the Case/Negligence –Indirect injuries –Requires proof of damage Particular torts INTENTIONAL TORTS • INTENTIONAL TORTS Trespass Conversion Detinue WHAT IS TRESPASS? • Intentional act of D which directly causes an injury to the P or his /her property without lawful justification •The Elements of Trespass: – fault: intentional act – injury must be caused directly – injury may be to the P or to his/her property – No lawful justification THE GENERAL ELEMENTS OF TRESPASS: The ‘DNA’ Intentional act + Direct interference with person or property + Absence of lawful justification + “x” element = A specific form of trespass SPECIFIC FORMS OF TRESPASS TRESPASS PERSON BATTERY ASSAULT FALSE IMPRISONMENT PROPERTY BATTERY • The intentional act of D which directly causes a physical interference with the body of P without lawful justification •The distinguishing element: physical interference with P’s body THE INTENTIONAL ACT IN BATTERY • No liability without intention • The intentional act = basic willful act + the consequences. THE ACT MUST CAUSE PHYSICAL INTERFERENCE • The essence of the tort is the protection of the person of P. D’s act short of physical contact is therefore not a battery •The least touching of another could be battery – Cole v Turner (dicta per Holt CJ) •‘The fundamental principle, plain and incontestable, is that every person’s body is inviolate’ ( per Goff LJ, Collins v Wilcock) Battery : The Nature of the Physical Interference Rixon v Star City Casino •D places hand on P’s shoulder to attract his attention; no battery Collins v Wilcock • Police officer holds D’s arm with a view to restraining her when D declines to answer questions and begins to walk away; battery SHOULD THE PHYSICAL INTERFERENCE BE HOSTILE? •Hostility may establish a presumption of battery; but •Hostility is not material to proving battery •The issue may revolve on how one defines ‘hostility’ THE INJURY MUST BE CAUSED DIRECTLY • Injury should be the immediate Case Law: The – Scott v Shepherd ( Lit squib/fireworks in market place) – Hutchins v Maughan( poisoned bait left for dog) – Southport v Esso Petroleum(Spilt oil on P’s beach) THE ACT MUST BE WITHOUT LAWFUL JUSTIFICATION • Consent is Lawful justification • Consent must be freely given by the P if P is able to understand the nature of the act – Allen v New Mount Sinai Hospital • Lawful justification includes the lawful act of law enforcement officers TRESPASS TO THE PERSON assault TRESPASS:ASSAULT • The intentional act or threat of D which directly places P in reasonable apprehension of an imminent physical interference with his or her person or of someone under his or her control • It is any act — and not a mere omission to act — by which a person intentionally — or recklessly — causes another to apprehend immediate and unlawful violence: State of New South Wales v Ibbett (2005) 65 NSWLR 168 • Two policemen gave chase to Mr Ibbett, suspecting that he may have been involved in a criminal offence. They pursued him to a house where he lived with his mother, Mrs Ibbett. Without legal justification, one of the policemen entered the property and arrested Mr Ibbett. His mother came into the garage where these events occurred. The police officer produced a gun and pointed it at Mrs Ibbett saying: • “Open the bloody door and let my mate in”. • Mrs Ibbett, who was an elderly woman, had never seen a gun before and was, not unnaturally, petrified. THE ELEMENTS OF ASSAULT • There must be a direct threat: – Hall v Fonceca (Threat by P who shook hand in front of D’s face in an argument) – Barton v Davis • In general, mere words are may not actionable – Barton v Armstrong • But mere silence as in silent telephone calls, may constitute an assault: R v Burstow; R v Ireland [1998] AC 147. • In general, conditional threats are not actionable – Tuberville v Savage – Police v Greaves THE ELEMENTS OF ASSAULT • The apprehension must be reasonable; the test is objective • The interference must be imminent – -Police v Greaves – Barton v Armstrong Zanker v Vartzokas (P jumps out of a moving van to escape from D’s unwanted lift) Zanker v Vartzokas and the issue of imminence/immediacy • The Facts: – Accused gives a lift to victim and offers money for sex; victim refuses. – Accused responds by accelerating car, Victim tries to open door, but accused increases acceleration – Accused says to victim: I will take you to my mates house. He will really fix you up – Victim jumps from car then travelling 60km/h Zanker v Vartzokas: The Issues Was the victim’s fear of sexual assault in the future reasonable? •Was the feared harm immediate enough to constitute assault? • Zanker v Vartzokas: The Reasoning • Where the victim is held in place and unable to escape the immediacy element may be fulfilled. • The essential factor is imminence not contemporaneity • The exact moment of physical harm injury is known to the aggressor • It remains an assault where victim is powerless to stop the aggressor from carrying out the threat THE GENERAL ELEMENTS OF TRESPASS Intentional act + Direct interference + Absence of lawful justification + “x” element = A specific form of trespass SPECIFIC FORMS OF TRESPASS TRESPASS PERSON BATTERY ASSAULT FALSE IMPRISONMENT PROPERTY FALSE IMPRISONMENT • The intentional act of D which directly causes the total restraint of P and thereby confines him/her to a delimited area without lawful justification • The essential distinctive element is the total restraint THE ELEMENTS OF THE TORT •It requires all the basic elements of trespass: – Intentional act – Directness – absence of lawful justification/consent , and • total restraint RESTRAINT IN FALSE IMPRISONMENT • The restraint must be total – Bird v Jones (passage over bridge) – Rudduck v Vadarlis – The Balmain New Ferry Co v Robertson • Total restraint implies the absence of a reasonable means of escape – Burton v Davies (D refuses to allow P out of car) • Restraint may be total where D subjects P to his/her authority with no option to leave – Symes v Mahon (police officer arrests P by mistake) ‘Correctional Cases’ • In State of New South Wales v TD (2013) 83 NSWLR 566, – Respondent suffering from mental illness was found guilty and sentenced to 20 months. Following a determination by the Mental Health Tribunal, the District Court was ordered that she be detained in a hospital. Contrary to this order, for some 16 days, the appellant was detained in a cell at Long Bay Goall in an area which was not gazetted as a hospital. • In State of New South Wales v Kable (2013) 87 ALJR 737, – the High Court of Australia held that a detention order which had been made by the Supreme Court (but under legislation which was later held invalid) provided lawful authority for Mr Kable’s detention. TRESPASS TO PROPERTY TRESPASS TO PROPERTY LAND GOODS/CHATTELS TRESPASS TO LAND • The intentional of D which directly interferes with the plaintiff’s exclusive possession of land THE NATURE OF THE TORT • Land includes the actual soil/dirt, the structures/plants on it and the airspace above it • Cujus est solum ejus est usque ad coelum et inferos –Bernstein of Leigh v Skyways & General Ltd –Kelson v Imperial Tobacco The Nature of D’s Act: A General Note •...[E]very invasion of private property, be it ever so minute, is a trespass. No man can set his foot upon my ground without my license, but he is liable to an action, though the damage be nothing.... If he admits the fact, he is bound to show by way of justification, that some positive law has empowered or excused him ( Entick v Carrington (1765) 16 St Tr 1029, 1066) THE NATURE OF D’S ACT • The act must constitute some physical interference which disturbs P’s exclusive possession of the land –Victoria Racing Co. v Taylor –Barthust City Council v Saban –Lincoln Hunt v Willesse THE NATURE OF THE PLAINTIFF’S INTEREST IN THE LAND • P must have exclusive possession of the land at the time of the interference exclusion of all others THE NATURE OF EXCLUSIVE POSSESSION • Exclusive possession is distinct from ownership. • Ownership refers to title in the land. Exclusive possession refers to physical holding of the land •The nature of possession depends on the material possessed THE POSITION OF TRESPASSERS AND SQUATTERS A trespasser/squatter in exclusive possession can maintain an action against any other trespasser •Newington v Windeyer (1985) 3 NSWLR • THE POSITION OF POLICE OFFICERS • Unless authorized by law, police officers have no special right of entry into any premises without consent of P. (Halliday v Neville) • A police officer charged with the duty of serving a summons must obtain the consent of the party in possession (Plenty v. Dillion ) TRESPASS TO PROPERTY TRESPASS TO PROPERTY LAND GOODS/CHATTELS TRESPASS TO PROPERTY TRESPASS TO PROPERTY LAND TRESPASS TO GOODS/CHATTEL • The intentional/negligent act of D which directly interferes with the plaintiff’s possession of a chattel without lawful justification • The P must have actual or constructive possession at the time of interference. • DAMAGES •It may not be actionable per se (Everitt v Martin) CONVERSION • The act of D in relation to another’s chattel which constitutes an unjustifiable denial of his/her title CONVERSION: Who Can Sue? • Owners • Those in possession or entitled to immediate possession – Bailees* – Bailors* – Mortgagors* and Mortgagees*(Citicorp Australia v B.S. Stillwell) – Finders (Parker v British Airways; Armory v Delmirie) ACTS OF CONVERSION • Mere asportation is no conversion – Fouldes v Willoughby • The D’s conduct must constitute an unjustifiable denial of P’s rights to the property – Howard E Perry v British Railways Board • Finders of lost property – Parker v British Airways • The position of the auctioneer – Willis v British Car Auctions • Destruction of the chattel is conversion – Atkinson v Richardson;) • Taking possession • Withholding possession – Clayton v Le Roy ACTS OF CONVERSION • Misdelivery ( Ashby v Tolhurst (1937 2KB); Sydney City Council v West) • Unauthorized dispositions in any manner that interferes with P’s title constitutes conversion (Penfolds Wines v Elliott) DETINUE • Detinue: The wrongful refusal to tender goods upon demand by P, who is entitled to possession It requires a demand coupled with subsequent refusal (General and Finance Facilities v Cooks Cars (Romford) DAMAGES IN CONVERSION AND DETINUE • In conversion, damages usually take the form of pecuniary compensation • In detinue, the court may in appropriate circumstances order the return of the chattel • Damages in conversion are calculated as at the time of conversion; in detinue it is as at the time of judgment – The Mediana – Butler v The Egg and Pulp Marketing Board – The Winkfield – General and Finance Facilities v Cooks Cars (Romford) THE LAW OF TORTS Action on the Case for Indirect Injuries INDIRECT INTENTIONAL INJURIES • ACTION ON THE CASE FOR PHYSICAL INJURIES OR NERVOUS SHOCK INDIRECT INTENTIONAL INJURIES: CASE LAW • Bird v Holbrook (trap set in garden) –D is liable in an action on the case for damages for intentional acts which are meant to cause damage to P and which in fact cause damage (to P) THE INTENTIONAL ACT • The intentional may be deliberate and preconceived(Bird v Holbrook ) • It may also be inferred or implied; the test for the inference is objective Wilkinson v Downton • Janvier v Sweeney •Nationwide News v Naidu • Action on the Case for Indirect Intentional Harm: Elements • D is liable in an action on the case for damages for intentional acts which are meant to cause damage to P and which in fact cause damage to P • The elements of this tort: – The act must be intentional – It must be one calculated to cause harm/damage – It must in fact cause harm/actual damage • Where D intends no harm from his act but the harm caused is one that is reasonably foreseeable, D’s intention to cause the resulting harm can be imputed/implied THE SCOPE OF THE RULE • The rule does not cover ‘pure’ mental stress or mere fright – Wainright v Home Office • The act must be reasonably capable of causing mental distress to a normal* person: – Bunyan v Jordan – Stevenson v Basham The Future of the Wilkinson v Downtown • The High Court obiter dicta Magill v Magill – Subsequent developments in Anglo-Australian law recognise these cases as early examples of recovery by reference to imputed intention to cause physical harm ; a cause of action later subsumed under the unintentional tort of negligence ( Per Gummow, Kirby and Crennan JJ) – Wilkinson v Downton, decided in 1987 and Janvier v Sweeney decided in 1919, which were cases of deception causing nervous shock, would probably now be explained either on the basis of negligence or intentional infliction of personal injury ( per Gleeson CJ) ONUS OF PROOF • In Common Law, he who asserts proves • Traditionally, in trespass D was required to disprove fault once P proved injury. Depending on whether the injury occurred on or off the highway ( McHale v Watson; Venning v Chin) • The current Australian position is contentious but seems to support the view that in off highway cases D is required to prove all the elements of the tort once P proves injury – Hackshaw v Shaw – Platt v Nutt – See Blay; ‘Onus of Proof of Consent in an Action for Trespass to the Person’ Vol. 61 ALJ (1987) 25 – But see McHugh J in See Secretary DHCS v JWB and SMB (Marion’s Case) 1992 175 CLR 218 IMPACT OF THE CIVIL LIABILITY ACT • Section 3B Civil liability excluded from Act (1) The provisions of this Act do not apply to or in respect of civil liability (and awards of damages in those proceedings) as follows: (a) civil liability in respect of an intentional act that is done with intent to cause injury or death or that is sexual assault or other sexual misconduct – the whole Act except Part 7 (Self-defence and recovery by criminals) in respect of civil liability in respect of an intentional act that is done with intent to cause injury or death THE LAW OF TORTS Defences to Intentional Torts INTRODUCTION: The Concept of Defence • Broader Concept: The content of the Statement of Defence- The response to the P’s Statement of Claim-The basis for non-liability •Statement of Defence may contain: Denial – Objection to a point of law – Confession and avoidance: – MISTAKE • An intentional conduct done under a misapprehension • Mistake is thus not the same as inevitable accident • Mistake is generally not a defence in tort law ( Rendell v Associated Finance Ltd, Symes v Mahon) • ‘Mistake’ may go to prove MEDICAL CASES CONSENT IN MEDICAL CASES • Medical practitioners must obtain consent from the patient to any medical or surgical procedure. • Absent the patient’s consent, the practitioner who performs a procedure will have committed a battery and trespass to the person. • Note that consent to one procedure does not imply consent to another. • Subject to any possible defence of necessity, the carrying out of a medical procedure that is not the procedure, the subject of a consent, will constitute a battery. Exercise • P was admitted for abdominal surgery for which he duly consented. While he was under general anesthetic, his surgeon noticed a sebaceous cyst on the top of his head. P is bald and the so the surgeon decided to do him a favour and get rid of the unsightly cyst. He removed it without incident. In the recovery ward, P was incensed when he discovered what had happened. His cyst had apparently been the source of many a free pint of ale. He habitually wore a bowler hat and it had been his habit to place a second, tiny bowler hat on top of the sebaceous cyst itself. Whenever he removed his hat at the local pub to expose the tiny bowler underneath, sitting on the cyst, this invariably caused general amusement and free shouts of beer. P was upset at the loss of the cyst, his one major social asset. • P has been advised that since he did not suffer any “real damage” he can hardly expect to succeed in a tort action against the surgeon. Do you agree? ‘EXTRA’ OR UNECESSARY MEDICAL PROCEDURE NOT AUTHORISED Exercise • P saw a dental surgeon following injury at work. Over a period of 12 months the surgeon performed root-canal treatment and fitted crowns on all of P’s teeth at considerable cost • Surgeon later admitted the crowns were unnecessary and he had been negligent • Issue could P argue trespass? Dean v Phung [2012] NSWCA 223 – Consent is validly given in respect of medical treatment where the patient has been given basic information as the nature of the proposed procedure. If however, it could be demonstrated objectively that a procedure of the nature carried out was not capable of addressing the patient’s problem, there would be no valid consent. – It is necessary to distinguish between core elements of the procedure and peripheral elements, including risks of adverse outcomes. Wrong advice about the latter may involve negligence but will not vitiate consent. – Burden of proof will lie on the practitioner to establish the existence of a valid consent where that is in issue. COMPETING PRINCIPLES •A competent adult’s right of autonomy or selfdetermination, or the right to control his or her own body, versus the interest of the State in protecting and preserving the lives and health of its citizens. Hunter and New England Area Health Service v A (2009) 74NSWLR 88 •A had prepared an advance care directive stating that he would refuse dialysis. He then developed renal failure and was being kept alive by mechanical ventilation and kidney dialysis. • McDougall J concluded that, when in conflict, the former principle should generally prevail Re JS [2014] NSWSC 302 • JS a 27 year old man requested hospital to stop providing him with life-sustaining treatment. The hospital sought a declaration from the NSW Supreme Court that it was entitled to discontinue the treatment. • JS had been a quadriplegic since the age of seven. And had needed full invasive ventilator support via a tracheotomy since that age. In 2013 his lungs collapsed. His condition worsened and required full-time care and treatment in hospital. His quality of life was significantly impaired. JS expressed a wish for that treatment to stop on his 28th birthday. Issue whether hospital could comply with his request: • Held: Medical practitioners would be acting lawfully if they acted in accordance with JS’s re MATURE MINORS GILLICK COMPETENCY • Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority [1986] 1 AC 112, – A mature minor who is capable of understanding the nature and consequences of a particular type of medical treatment, can provide effective consent to such treatment • Secretary Department of Health and Community Services v JWB (Marion’s case) (1992) 175 CLR 218 • s 49(2) of the Minors (Property and Contracts) Act 1970 (NSW) provides that children over the age of 14 are able to consent to medical and dental treatment Children and Young Persons (Careand Protection) Act 1988(NSW) •s 174: Protection to medical practitioners who give e mergency or urgent medical treatment in circumstances where such treatment is necessary to save the life of a minor • The Act is however silent on whether a mature minor can refuse treatment THE PARENS PATRIAE JURISDICTION OF COURTS • It originates from the Crown’s obligation to make decisions for those who are not able to care for themselves, such as minors or those of “unsound mind” • The jurisdiction of the court is invoked with caution: – the court must act cautiously, not as if it were a private person acting with regard to his own child, and acting in opposition to the parent only when judicially satisfied that the welfare of the child requires that the parental right should be suspended or superseded ( In Re O’Hara [1900] 2IR 232 • The guiding principle is the best interest or welfare of the child within its jurisdiction X v The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network [2013] NSWCA 320 – X a teenager refused to receive his own treated blood products. The treatment was necessary to preserve his life; his refusal was based on his religious beliefs. His refusal was fully supported by his parents who were of the same religious persuasion. – The court, exercising its “parens patriae” jurisdiction, essentially overrode these genuine beliefs, holding that the welfare of the patient required that the primary judge make the order permitting the treatment. CONSENT IN SPORTS •http://www.youtube.com/watch?v= W-BmKXU12yE • Alex McKinnon has been diagnosed as a quadriplegic and warned by doctors he may never walk again after this tackle. Jordan McLean was suspended for seven weeks after being found guilty of a 'dangerous throw' on Newcastle Knights player Alex CONSENT IN SPORTS (2) •In contact sports, consent is not necessarily a defence to foul play (McNamara v Duncan; Hilton v Wallace) • To succeed in an action for trespass in contact sports however, the P must of course prove the relevant elements of the tort. – Giumelli v Johnston SELF DEFENCE, DEFENCE OF OTHERS • A P who is attacked or threatened with an attack, is allowed to use reasonable force to defend him/herself • In each case, the force used must be proportional to the threat; it must not be excessive. (Fontin v Katapodis) • D may also use reasonable force to defend a third party where he/she reasonably believes that the party is being attacked or being threatened THE DEFENCE OF PROPERTY • D may use reasonable force to defend his/her property if he/she reasonably believes that the property is under attack or threatened • What is reasonable force will depend on the facts of each case, but it is debatable whether reasonable force includes ‘deadly force’ (See CLA 52(3) for the scope ) Section 52 CLA • No civil liability for acts in self-defence – (1) A person does not incur a liability to which this Part applies arising from any conduct of the person carried out in self-defence, but only if the conduct to which the person was responding: – (a) was unlawful, or – (b) would have been unlawful if the other person carrying out the conduct to which the person responds had not been suffering from a mental illness at the time of the conduct. – (2) A person carries out conduct in self-defence if and only if the person believes the conduct is necessary: – (a) to defend himself or herself or another person, or – (b) to prevent or terminate the unlawful deprivation of his or her liberty or the liberty of another person, or – (c) to protect property from unlawful taking, destruction, damage or interference, or – (d) to prevent criminal trespass to any land or premises or to remove a person S52 Cont’ed • and the conduct is a reasonable response in the circumstances as he or she perceives them. • (3) This section does not apply if the person uses force that involves the intentional or reckless infliction of death only: – (a) to protect property, or – (b) to prevent criminal trespass or to remove a person committing criminal trespass. Section 53 CLA Damages limitations apply even if selfdefence not reasonable response • If section 52 would operate to prevent a person incurring a liability to which this Part applies in respect of any conduct but for the fact that the conduct was not a reasonable response in the circumstances as he or she perceived them, a court is nevertheless not to award damages against the person in respect of the conduct unless the court is satisfied that: • (b) in the circumstances of the case, a failure to award damages would be harsh and unjust. PROVOCATION • Provocation is not a defence in tort law. • It can only be used to avoid the award of exemplary damages: Fontin v Katapodis; Downham Ballett and Others The Case for Allowing the Defence of Provocation • The relationship between provocation and contributory negligence • The implication of counterclaims •Note possible qualifications Fontin v Katapodis to: – Lane v Holloway – Murphy v Culhane – See Blay: ‘Provocation in Tort Liability: A Time for Reassessment’,QUT Law Journal, Vol. 4 (1988) pp. 151-159. NECESSITY • The defence is allowed where an act which is otherwise a tort is done to save life or property: urgent situations of imminent peril Urgent Situations of Imminent Peril • The situation must pose a threat to life or property to warrant the act: Southwark London B. Council v Williams • Lord Denning MR: – ‘If homelessness were once admitted as a defence to trespass, no one’s house could be safe. Necessity would open a door no man could shut. It would not only be those in extreme need who would enter. There would be others who would imagine they were in need or would invent a need, so as to gain entry. The plea would be an excuse for all sorts of wrongdoing. So the courts must refuse to admit the plea of necessity to the hungry and the homeless: and trust that their distress will be relieved by the charitable and good.’ • The defence is available in very strict circumstances R v Dudley and Stephens • D’s act must be reasonably necessary and not just convenient Murray v McMurchy – In re F – Cope v Sharp INSANITY • Insanity is not a defence as such to an intentional tort. • What is essential is whether D by reason of insanity was capable of forming the intent to commit the tort. (White v Pile; Morris v Marsden) ILLEGALITY: Common Law • Persons who join in committing an illegal act have no legal rights inter se in relation to torts arising directly from that act. – Hegarty v Shine – Smith v Jenkins (D injured while he and accomplice drive stolen vehicle) – Jackson v Harrison ( P not barred from claiming merely because he was aware that D had lost his license) – Gala v Preston ILLEGALITY: The CLA • Section 54: Criminals not to be awarded damages – A court is not to award damages in respect of liability to which this Part applies if the court is satisfied that: – (a) the death of, or the injury or damage to, the person that is the subject of the proceedings occurred at the time of, or following, conduct of that person that, on the balance of probabilities, constitutes a serious offence, and – (b) that conduct contributed materially to the death, injury or damage or to the risk of death, injury or damage. – (2) This section does not apply to an award of damages against a defendant if the conduct of the defendant that caused the death, injury or damage concerned constitutes an offence (whether or not a serious offence). The CLA and Intentional Torts • S3B:(1) The provisions of this Act do not apply to or in respect of civil liability (and awards of damages in those proceedings) as follows: • (a) civil liability of a person in respect of an intentional act that is done by the person with intent to cause injury or death or that is sexual assault or other sexual misconduct committed by the person-the whole Act except: •… • (ii) Part 7 (Self-defence and recovery by criminals) in respect of civil liability in respect of an intentional act that is done with intent to cause injury or death, and The Exclusion of Intentional torts from the CLA • New South Wales v Ibbet: Assault and trespass to land: The restrictions on the award of exemplary and aggravated damages under the CLA held not to apply • Honda v NSW [2005]: wrongful arrest, malicious prosecution and false imprisonment by a police officer. Issue whether injury in s3B included only bodily injury. Held injury not limited to bodily injury • Zorom Enterprise v Zabow: P suffered head injuries as a result of an attack by a security guard employed by D. P sued D for vicarious liability. D argued that CLA restrictions applied because s3B only excluded only the intentional acts of the person who actually committed torts and not the D who was only vicariously liable. Argument was rejected s3B: ‘In respect of ….’ • NSW v Bujdoso [2007] • P was attacked by inmates while in prison. He brought an action the D for their negligence. Since the conduct of the inmates was intentional, the issue was whether the provision of 3B applied to exclude the restrictions of the CLA in the award of damages. • The argument centred on the phrase ‘in respect of’ P argued that in respect of was broad and means that D’s liability arose in respect of the intentional act of the inmates and so s3B applied. The court rejected the argument. In respect of interpreted to refer to the person who did the act and the person whose negligence led to the doing of the act.