Enabling Seniors to Overcome Barriers in Health Care Communication

advertisement

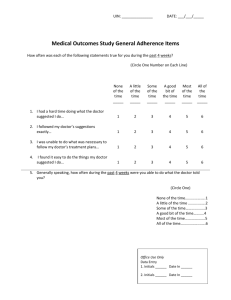

Enabling Seniors to Overcome Barriers in Health Care Communication William Godolphin1, Angela Towle1, Sheila Dyer2, Donald Cegala3, Jennifer Manklow4, Holly Wiesinger4 & Lionsview Seniors’ Planning Society5 1Informed Shared Decision Making Project, Division of Health Care Communication, College of Health Disciplines, University of British Columbia, Vancouver BC Canada V6T 1Z3, Tel: (604) 822-8002, Email: isdm@interchange.ubc.ca 2Clinical Skills Resource Centre, Standardized Patient Client Program, Vancouver BC Canada 3Professor of Communication and Family Medicine, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio USA 4Medical Undergraduate Program, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver BC Canada 5North Vancouver BC Canada Supported by the Vancouver Foundation 2000, 2002 Communications Skills Training for Patients Communications skills training for patients directly associated with physicians’ offices has been shown in research studies to make a difference in the nature of the interaction (more questions and control by patients) and improved outcomes (disease-related, functional status and adherence to treatment). But - community-based interventions have the potential for greater dissemination, lower cost and are consistent with the patient empowerment movement. Objective To develop, implement and evaluate a community-based workshop to assist seniors to communicate more effectively with their physicians. University-Community Partnership Research UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Needs Assessment Workshop Telephone interviews.. Implementation .. with 21 seniors following a community workshop “High blood pressure: What are your risks and can they be reduced with prescription drugs?”. They were asked if they discussed what they had learned with their physicians and about the response they received. .. with 8 seniors interested in a workshop to improve communications with their doctors. Take home booklet (http://patcom.jcomm.ohio-state.edu) Workshop Model 1½ hours with a break for tea & biscuits 1. Use of PACE communications skills structure Though the quality of communication they described appeared to be less than satisfactory they made excuses for the physician. 2. A simulated office interview between doctor and patient illustrating common health and communications problems Conclusions Implications for workshop design They could not imagine how they might make a difference. provide a vicarious experience They were very tolerant of poor communication - up to a point beyond that their only response was to ‘fire the doc’. It was difficult to focus on what they might do to improve Communication. They had no control in the medical interview. teach them conflict negotiation skills 3. Facilitated discussion and role scripting/playing to explore solutions to the communications problems 3. Facilitators’ Guide Introductions: What do you expect when you see your doctor? Explanation of PACE framework. 1st video clip: Identify skills the patient demonstrates 2nd video clip: What are sources of conflict? What did the patient do that was helpful? Not helpful? What could you do if you are not like the patient? 3rd video clip: Work in pairs to write a dialogue to resolve the conflict and stay on PACE. Facilitators circulate to the groups. Read out (or better yet, act out) the scripts. Cegala et al: Patient Educ Counseling 2000; 41: 209-222 They were asked to describe communications problems and what they would like to be able to do about them. They described a general sense of dis-empowerment when faced with the medical profession. Asking questions if desired information is not provided. (information seeking) Expressing any concerns about the recommended treatment. A variety of barriers to discussion with their physicians included lack of time, lack of doctor’s interest and ‘doctor knows best’. Focus group .. Presenting detailed information about how you are feeling. (information providing) Checking your understanding of Co-facilitation by professional (coinformation given to you. (information investigator) and volunteer (senior) verifying) They shared the information widely with friends and family They wanted to focus on what the doctor should do. The Seniors Benevolent Fund The Roy and Bertha Wrigley Fund Presented at community centres associated with ‘keep well’ program for seniors and promoted by co-investigators (community partners: LSPS). 1. PACE Communications Skills Model 4th video clip: Compare outcomes with discussion of scripts. Closure: What will you try? Hand out booklet. Based on personal experience(s) of seniors involved in ‘standardized patient/client’ program. Acceptability: 57 participants at 5 workshops indicated lots of enthusiasm and support for the project (verbally and in written evaluations). Word-of-mouth prompted other seniors’ organizations, patient support groups and community centres to request workshops. Effectiveness: Post-workshop ‘opinionnaires’: the most frequently identified learning was about preparation (eg, “How to get ready for our visit”) and presentation (eg, “The importance of giving a clear history of the problem”) Follow up A long-term doctor-patient relationship, with good rapport Two months after workshops 9 participants took part in telephone interviews that were audio taped. Interviews were semi-structured and lasted 10-15 minutes. Workshop on talking with your doctor Sources of conflict: • Treatment preference • Peter’s enthusiasm about the locum (doctors have feelings too!) Peter illustrates each of the elements of PACE and conflict negotiation skills. 7 minute interview in 4 sections: - small talk and presentation - development - impasse - resolution Interview transcripts were subjected to Grounded Theory analysis Examples of change were reported .. Change was limited by: Communicate expectations: “I learned to be more forthright and tell him exactly what it was I wanted from him.” Expressed satisfaction with existing relationship; low drive to change. Most barriers to communications were attributed to the doctor; beyond patient’s control. Expressing concerns: “There was a bump on my abdomen and he said, ‘Oh what’s that?’ And I just passed it off and then I got home and I was worried about it, ‘ I wonder if I’ve got an aneurysm.’ And so, when I went back I asked him and I might not have done that before the workshop.” Importance of maintaining good rapport; attempts to make a change are perceived to put rapport at risk. The difficulty of changing an established relationship; lack of tactics to signal this intent. Asking questions: “The specialist - I had some questions that I wanted to know, so I thought about them before going.” .. but the subjects identified specific communications difficulties; on analyses these were categorized as: “Most of the time I felt that I was intruding on their time ... I felt that they wanted it to be over and done with in the 4 minutes and 59 seconds.” Dr Joan & Peter “Well you’re already in an inferior position ... with you sitting down below and they’re standing up, looking down at you, you know, that’s, well, intimidating.” Conclusions Change is slow and difficult and needs support and reinforcement. Sustainability requires embedding in existing programs and training of local facilitators. Perceived risk to rapport requires endorsement of workshop by physicians. They need ‘evidence’ (role models, testimonials) of what is possible — countering disempowerment by demonstrating it can be done — that they can put these skills into practice. Next Steps Presenting information: “I might not have told him about how I was feeling without that workshop. I was feeling very vague, not very great. I was rather surprised that he was concerned but I think he was concerned because I do have a chronic condition. Lo and behold it was that. So I’m on antibiotics. Caught it early because I did tell him.” “I’m afraid that I feel that I can’t do much about fostering a good relationship between the doctor and me because I think that’s something they don’t teach in university and [doctors] don’t learn it in medical school.” Futility “I think the doctors maybe feel that the patient Time wouldn’t understand Communication anyway if they tried to Difficulties explain it to them in little words.” Reluctance to Anxiety Language bother doctor provide for problem-solving and simulated practice teach them a structure for communications Evaluation Efficiency: The high cost of professional facilitator cannot be sustained in the community 2. Video Scenario Peter had unusually severe asthma attacks while his GP Dr Joan was on holiday. Peter now wants to try some ‘alternative’ therapy (eg, yoga suggested by locum). Dr Joan does not approve and is concerned about full investigation of his worsening asthma. Evaluation & Follow up Memory “Usually I forget something or the other I wanted to talk about.” “You’re always feeling that you shouldn’t bother them too much. In fact, they have a sign on the door, ‘only one problem per visit.’” Follow up intervention to reinforce the learning and support problem-solving. Embed in existing community programs by training volunteer peer facilitators who are also role models. Similar workshops for other patient groups. The major difference will be the video scenarios. ‘Endorsement’ from physician professional body, eg, licensing college or medical association. Our current funding focuses on more seniors’ groups, a support group for stroke patients and a community mental health program. These are high health care users and in an ‘information’ age they are disadvantaged in accessing information and more likely to be disempowered in the doctorpatient encounter.