PACES: Project, Argument, Claims, Evidence, Strategies

advertisement

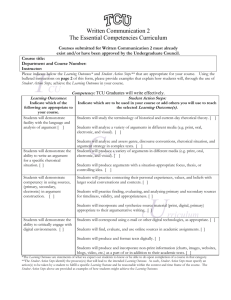

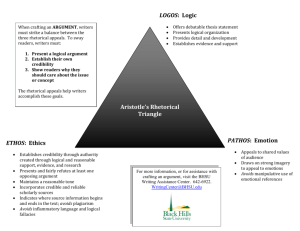

An Overview of RWS100: The Rhetoric of Written Argument Chris Werry, San Diego State University, cwerry@mail.sdsu.edu Course Materials ■ The RWS100 Wiki: https://sdsuwriting.pbworks.com Contains course and teaching materials ■ Materials from this talk: https://sdsuwriting.pbworks.com/swccd Texts Useful for Teaching Classes like RWS100 ■ Graff, Gerald and Cathy Birkenstein. They Say/I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing. ■ John Bean, Virginia Chappell and Alice M. Gillam. Reading Rhetorically. ■ John C. Bean, Engaging Ideas: The Professor's Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom. ■ Joseph Harris, Rewriting: How to Do Things with Texts Materials in this handout PACES: Project, Argument, Claims, Evidence, Strategies ........................................................ 2 Unit 1: Sample Activities ............................................................................................................ 3 Activities Repeated Over the Semester....................................................................................... 4 Some Questions to Ask Any Text ............................................................................................... 7 Charting a Text ........................................................................................................................... 8 Example of Charting ................................................................................................................... 9 Identifying Claims .................................................................................................................... 10 Sample Argument Map ............................................................................................................. 11 Assignment & Prompt............................................................................................................... 12 Sample Assignment 1 Prompt ................................................................................................... 12 Outline for Introduction ............................................................................................................ 13 Template Sentences for Strategy Section ................................................................................. 14 Templates from They Say/I Say ................................................................................................ 15 Quick Guide to Quotations (See Graff et al., “The Art of Quoting”) ....................................... 16 Example of a Rhetorical Move: Metadiscourse ........................................................................ 17 1 PACES: Project, Argument, Claims, Evidence, Strategies Project: An author’s project describes the kind of work she sets out to do – her purpose and the method she uses to carry it out. It is the overall activity that the writer is engaged in--researching, investigating, experimenting, interviewing, documenting, etc. Try to imagine what the author’s goals or hypotheses were as she wrote the text. To articulate a project—and to write an account— you need a verb, such as “researches,” “investigates,” “studies,” “presents,” “connects A with B,” etc. Argument: In the broadest sense, an argument is any piece of written, spoken, or visual language designed to persuade an audience or bring about a change in ideas/attitudes. Less broadly, in academic writing the argument often refers to the main point, assertion or conclusion advanced by an author, along with the evidence and reasoning by which this is established. Arguments are concerned with contested issues where some degree of uncertainty exists (we don’t argue about what is self-evident or agreed upon). Claims: To make a claim is to assert that something is the case, and to provide evidence for this. Arguments may consist of numerous claims and sometimes also sub-claims. Claims in academic writing often consist of an assertion, the staking out of a position, the solution to a problem, or the resolution of some shortcoming, weakness or gap in existing research. Often comes with self-identification (“my point here is that…”) emphasis (“It must be stressed that…”) approval (“Olson makes some important and long overdue amendments to work on …”) or a problem/solution or question/answer framework. Evidence: The component of the argument used as support for the claims made. Evidence is the support, reasons, data/information used to help persuade/prove an argument. To find evidence in a text, ask what the author has to go on. What is there to support this claim? Is the evidence credible? Some types of evidence: facts, historical examples/comparisons, examples, analogies, illustrations, interviews, statistics (source & date are important), expert testimony, authorities, anecdotes, witnesses, personal experiences, reasoning, etc. Strategies: Rhetorical Strategy: a particular way in which authors craft language—both consciously and subconsciously—so as to have an effect on readers. Strategies are means of persuasion, ways of gaining a readers’ attention, interest, or agreement. Strategies can be identified in the way an author organizes her text, selects evidence, addresses the reader, frames an issue, presents a definition, constructs a persona or establishes credibility, appeals to authority, deals with opposing views, uses “metadiscourse,” makes particular use of style and tone, draws on particular tropes and images, as well as many of the other textual choices that can be identified. Hmm.. . 2 Unit 1: Sample Activities First 2-3 Weeks: Introduce the course, key concepts, & apply to short texts 1) Introduce RWS100, rhetoric, course goals 2) Introduce key concepts for first part of semester (argument, claims, reasons, evidence, rhetorical moves, charting, etc.) 3) Introduce rhetoric and rhetorical situation with “reflexive” texts (SubText, Parry, etc.) and writing exercises where students examine their own rhetorical choices. 4) Practice applying concepts to short texts – advertisements, excerpts from a speech, tv clips, visual texts, etc. (you can choose new texts, or use ones we’ve selected.) 5) Apply these concepts to short texts - Kristof (“War & Wisdom”), Bleich (“California's HigherEducation Debacle”) Rifkin (“A Change of Heart About Animals”), Parry (“The Art of Branding a Condition”), Foster Wallace (“This is Water”) etc. OR, see texts in Praxis, or the FrankenReader texts on the wiki. There is also a collection of teaching resources for these short texts on the wiki and Blackboard you can use. Unit 1: PACES & First Assignment 1) Introduce assignment 1, the text, and work to be done 2) Introduce pre-reading and critical reading strategies – finding clues to purpose, audience, genre, context; looking at layout, headings etc.; annotating the text, posing questions, etc. 3) Assign questionnaire/activities to get students thinking about general issues raised in text, how their experiences/ideas may connect to the text, and to identify some assumptions often held by readers (use later on to explore moves the author makes to deal with assumptions) 4) Begin discussion of Pinker– focus on key passages, introduce main issues, present examples from other sources to illustrate claims. Give vocabulary quizzes to make sure students read closely and/or model close reading of texts. 5) Jigsaw research activities (assign students background research to do on text – for example, could ask them to research Pinker, his other work, recently published books, some of the terms used, the texts/figures referred to, etc) 6) Work on identifying major elements of the argument - claims, evidence, project, appeals, etc. Explain ways of talking about these elements (e.g., phrases for talking about argument). 7) “Charting,” Moves & Strategies. Chart Pinker– identify what the text does (structure + the moves made). Work on identifying and analyzing rhetorical strategies - what the strategy is, how it works, why it is used 8) Draft sections of paper – how to organize the introduction; writing about author’s argument and project; using rhetorical précis, and “template phrases” from They Say/I Say to produce a sophisticated account of the argument; managing quotations (see They Say/I Say); writing about strategies (what, how, why) 9) Using metadiscourse to guide the reader (see They Say/I Say and handouts) 10) How to write the conclusion 11) Models and sample papers: work with sample intros and body paragraphs, and with sample student papers. Have students chart and grade sample student papers. Have students chart their own papers, explaining the moves they are making (can have them hand this in with draft). Students chart their peer’s paper also in peer review. 12) Editing, revising, peer review, review plan, conferencing 13) After drafts are received, you may want to address grammar/sentence level issues by focusing on problems that are shared across clusters of papers. Can have students look up the mechanical issues in Penguin handbook and write short diagnosis or report on this, to be handed in with final paper (can be extra credit). 3 Activities Repeated Over the Semester The following is a list of concepts and activities that we will return to a number of times during the semester. They are in summary form - handouts explaining them in more detail, plus exercises and further activities, are available on the wiki and Blackboard. You may decide to use a different set of activities, but many teachers use these as a framework, especially in their first few semesters of teaching. Pre-reading 1: finding clues to purpose, context, audience, etc. Pre-reading strategies are explored in order to help students find clues to purpose, context and audience. SKIM – things we do. Title, author, date, publisher, genre, works cited, etc. Students will consider how titles, subtitles, headings, visuals, structural divisions, format, genre, layout, design and other textual elements can tell us a great deal about a text before we have read it Pre-reading 2: using questionnaires, general issue questions, and pre-discussion to prime students for discussion of a text. Posing questions that get students thinking about the general issues raised in a text. Questionnaires that identify student assumptions about issues, and can be connected later to elements of the text (“if a common assumption about the issue is X, then perhaps the authors knows this and uses strategy Y to address the assumption). Finding connections to issues raised in text and things going on in the world at present. E.g. Gladwell and the extent to which social media enables new forms of political expression, or Pinker and the question of where human morality comes from. “Jigsaw” work – assign students/groups to research the author, key terms/references, the publication, etc. to get at key info, to get students used to asking key questions, and to help them figure out where to go to find such information. Critical/Active Reading and Rhetorical Reading Explore ways of annotating texts. Model how to pose questions, interrogate assumptions, read actively and critically. Adler’s “How to Mark a Text” can be useful. See “Questions to Ask Any Text” handout. Discussion & Discussion Starters Class discussion of main texts. There are a range of strategies you can use to jump start discussion and encourage participation. These include freewriting (gives students time to formulate ideas), group work, homework posted to Blackboard, calling by name, etc. Charting Charting is a form of close reading in which students attend to what the text “does” (rather than merely what it “says.”) Charting involves annotating a text in order to show the “work” each paragraph is doing, or the “moves” being made. This is a core concept for the semester. Each annotation must begin with a verb: introduce, claim, support, present evidence, qualify, rebut, contrast, satirize, etc. Charting helps keep students focused on issues of agency, purpose, choice and strategy - reminding them that behind every sentence there is an author with intent who makes rhetorical choices to achieve her aim. It is also designed to move students toward identifying relationships between ideas and locating claims, evidence, and the main argument. Charting exercises are also used with student texts - in revision and peer review. Charting can be confusing at first. One way of thinking about it is just as a form of close reading that prompts students to consider the choices authors make and the strategies they draw on. It's also helpful to get students to consider how parts of the text connect to each other. Charting is an open ended process, and the main thing is to get students to slow down, bracket content, and consider what a text does, how it does it, and why. It isn't a particular methodology with rules. I've sometimes used the analogy of the slow motion "frame advance" feature on a DVD player. You can use this to slow a visual text right down and 4 focus on how a scene is composed, what is foregrounded and backgrounded, what point of view is established, the connections between segments of a text, etc.. Pre-writing Exercises Students will be given a series of pre-writing exercises designed to help them master elements of each assignment. These pre-writing exercises break the writing, reading and reasoning skills of major assignments into a set of smaller, more manageable tasks that students often complete in class or as homework. Many of these exercises will involve the concepts described below – charting; identifying the argument/claim/evidence/project; template phrases, the rhetorical précis, etc. Identifying the argument, claims, evidence and project and strategies (PACES) With every text students will spend time identifying the argument, major claims, evidence and project. The argument, major claims, and evidence are described in other handouts. The project articulates the kind of work that a writer is setting out to do and the overall activity that the writer is engaged in-researching, investigating, experimenting, interviewing, documenting, etc. The “project” describes what the author sets out to do, how she does it, and by what means (such as research connections between X and Y, or applying a definition of X to Z phenomenon in such and such a way, etc.) To articulate a project—to write an account— you need a verb, such as “researches,” “investigates,” “studies,” “presents,” “connects A with B,” etc. Exploring Rhetorical Strategies Rhetorical strategies are particular ways writers craft language so as to have an effect on readers. Strategies are means of persuasion, ways of using language to get readers’ attention and agreement. Some common rhetorical strategies are metadiscourse, definitions, framing devices, ethos, pathos, logos, rebuttals, qualifications, etc. Students are asked to 1) identify rhetorical strategies, 2) describe how they work, and 3) describe why they are used – what purpose do they accomplish? Developing a Rhetorical Analysis This involves taking the work done with charting and identifying strategies using this to write an analysis that focuses on what the author is doing – how the author frames an issue, summarizes previous research, presents evidence, deals with objections or signposts the organization of text, etc. Template Phrases Template phrases are used to model parts of the central rhetorical moves academic writers make. We will often give students templates that provide some of the linguistic “scaffolding” for introducing a text, capturing key elements of an argument, signaling the topic of a paper, and in particular working with sources and describing connections between texts. Fill-in-the-blank sentences may seem overly formulaic, but they are important tools for practice, and can become a useful tool for invention. A number of templates can be found in Gerald Graff and Kathy Birkenstein’s book They Say/I Say. The Rhetorical Précis A rhetorical précis is a four-sentence paragraph that records the essential rhetorical elements of an author’s argument. The précis includes the name of the speaker/writer(s), the context or situation in which the text is delivered, the major assertion, the mode of development for or support of the main idea, the stated and/or apparent purpose of the text, and the relationship between the speaker/writer(s) and the audience. It is designed to move students away from summary and towards writing that shows a more sophisticated understanding of a text’s rhetorical situation. The précis is designed to highlight key elements of the rhetorical situation, help students with reading comprehension, and improve treatment of source materials in their writing. We will use it often over the course of the semester. 5 Metacommentary (aka metalanguage/metadiscourse) Metacommentary is self-reflective linguistic material referring to the evolving text and to the imagined reader of that text. It consists of moments in a text when the author stands back and talks about her text/argument itself. Metacommentary reveals the ways that writers signal their attitude towards both the propositional content and the audience of the text. Often, metadiscourse announces what a paper will be about, what it will do, what its project, purpose and argument will be. Metadiscourse also provides signposts to the author’s argument, guiding the reader to what will come next and showing how that is connected to what has come before. Students will spend time examining and producing various forms of metacommentary. Reflective Writing Reflective writing involves students thinking carefully about their writing, how it is developing, considering their own rhetoric, etc. Before final papers are due you can have students apply course concepts to their own writing – e.g. chart their own writing, examine the strategies they use, how their argument is structured, etc. That is, they can use tools of analysis to reflect on and evaluate their writing. After papers are due, reflective writing can be used to deepen understanding of their writing. 6 Some Questions to Ask Any Text These questions can be posed to any text, and can help you start thinking about texts from a rhetorical perspective. THE BIG PICTURE 1. Who is the audience? Who is the author trying to reach? (age, gender, cultural background, class, etc.) Which elements of the text – both things included, and things left out – provide clues about the intended audience? How does the author represent the audience 2. Who is the author, and where is she coming from? What can you find out about the author? What can you find out about the organization, publication, web site, or source she is writing for? 3. What is the author’s purpose? What is the question at issue? Why has the author written this text? What is the problem, dispute, or question being addressed? What motivated her to write, what does she hope to accomplish, and how does she hope to influence the audience? 4. What is the context - what is the situation that prompted the writing of this text, & how do you know? When was the text created, and what was going on at the time? Can you think of any social, political, or economic conditions that are particularly important? 5. What “conversation” is the author part of? It’s unlikely the author is the first person to write on a particular topic. As Graff points out, writers invariably add their voices to a larger conversation. How does the author respond to other texts? How does she enter the conversation (“Many authors have argued X, but as Smith shows, this position is flawed, and I will extend Smith’s critique by presenting data that shows…”) How does the author position herself in relation to other authors? 6. How does the author claim “centrality,” i.e. establish that the topic being discussed matters, and that readers should care? 7. What is the author’s “stance”? What is his attitude toward the subject, and how does this come across in his language? 8. What research went into writing the text, & what material does the author examine? (project) ARGUMENT & PERSUASION 1. What is the most important sentence in this text, to you? Why? 2. What is the author’s overall argument, or central claim? 3. What are the most important (sub) claims? 4. How does the author establish her authority/credibility? (ethos) 5. How does the author connect with your emotions? (pathos) 6. What evidence or reasons does the author provide, and do they convince you? (logos) 7. What are you being asked to believe, think, or do? (persuasion) 8. How is the text organized? Why do you think the author organized the text this way? What effect does it have? 9. Does the author respond to other arguments, and if so, are they treated fairly? 10. How do the author’s stylistic choices reinforce or advance the argument? How do word choice, imagery, metaphor, design, etc. help persuade? 11. How does the author frame the issues? Does the author’s representation of the issue or problem invite the audience to see things from a particular perspective? How does this help persuade? 12. How does the author define the central terms being discussed? How does this help persuade? 13. What assumptions can you identify? What does the author take for granted, and what does this tell you about her argument? 14. What implications follow from the author’s argument? 15. Does the author use metadiscourse? Are there moments when the author talks about what he is doing, or addresses the audience directly? Is this persuasive? How? 7 Charting a Text Charting1 involves annotating a text in order to show the “work” each paragraph, group of paragraphs, or section is doing. Charting helps identify what each part of the text is doing as well as what it is saying—helping us move away from summary to analysis. There are two strategies for charting that we’ll look at: macro-charting and microcharting. MACRO-CHARTING How do we do macro-charting? • Break text down into sections--identify “chunks” or parts of the text that seem to work together to DO something for the overall argument. • Draw lines between sections and label each one, annotating them with “doing” verbs: providing context, making a claim, supporting a claim, rebutting counter argument, illustrating with personal anecdote, describing the issue, etc. Why do we do macro-charting? • Macro-charting helps with understanding structure of argument, as well as locating claims, supporting evidence, and main argument. • Macro-charting guides students toward identifying relationships between ideas. • Macro-charting brings awareness that behind every sentence there is an author with intent who makes rhetorical choices to achieve his/her aims. MICRO-CHARTING How do we do micro-charting? • Break down sections of text by paragraph to analyze what each paragraph is doing for the overall argument. • Detail the smaller “moves” and strategies made within paragraphs: note when, where, and how and author makes a claim, cites evidence, and/or supports his/argument using a rhetorical strategy. Why do we do micro-charting? • Micro-charting can serve as a way to thoroughly understand in a detailed way how a text is put together. • Micro-charting encourages readers to look more carefully and closely at a text and helps us to focus our reading on tasks asked for in prompts. • Micro-charting brings awareness of the specific rhetorical choices made throughout a text (addressing particular audiences by making deliberate moves). 1 Adapted from work by Micah Jendian and Katie Hughes 8 Example of Charting 9 Identifying Claims Identifying claims – a good rule of thumb is to look for the following cues: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. question/answer pattern problem/solution pattern self-identification (“my point here is that…”) emphasis/repetition (“it must be stressed that…”) approval (“Olson makes some important and long overdue amendments to work on …”) metalanguage that explicitly uses the language of argument (“My argument consists of three main claims. First, that…”) Which sentences are claims? Which pattern do they follow? (Oreskes’ “The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change: How Do We Know We’re Not Wrong?”) “What is the scientific consensus on climate change, and how do we know it exists?” 66 “This latter point is crucial and merits underscoring…” 74 “It is important to distinguish among what is happening now…” 77 “Year after year, the evidence that global warming is real and serious has only strengthened. Perhaps that is the strongest argument of all. Contrarians have repeatedly tried to falsify the consensus, and they have repeatedly failed.” (89) “This book deals with…this chapter addresses a different question: might the scientific consensus be wrong?” (66) “First, let’s make clear what the scientific consensus is…Second, to say that global warming is real and happening is no the same as agreeing about what will happen in the future…” (73) “This suggests something discussed elsewhere in this book…” (74) “Is there disagreement over the details of climate change? Yes. Does this… 76 “So why does the public have the impression of disagreement among scientists? (76) Grouping and Creating a Hierarchy of Claims Some Claims & Sub-Claims – How Would You Rank These in Importance? Which belong together? ■ The public falsely believes that there is disagreement due to conceptual “conflations” made by contrarians (scientific and political uncertainty; mode and tempo; current science versus predicting future), misleading arguments put forward by interest groups, and the failure of scientists to communicate with public. (76 - 78) ■ Politically motivated groups have tried to manufacture uncertainty and mislead the public through a variety of strategies (75, 78) ■ Scientists reason in ways that are comparable to the way lawyers reason – they look for independent lines of evidence that hold together (90). ■ No scientific conclusion can ever be proven, uncertainty is unavoidable, and new evidence may lead us to change our views, but GCC is not a mere “belief,” and is instead our best current understanding, and “best basis for reasoned action.” (79) ■ The common /traditional view of the scientific method is wrong; there is no one single scientific method that will guarantee validity. Instead, there is a collection of standards and methods for evaluating scientific reliability, and HIGCC passes all of these. ■ HIGCC stands up to the inductive model – it can be shown to rest on a strong inductive base. (81) ■ HIGCC stands up to the deductive model, supporting predictions and hypotheses that have been shown to be valid (83-84). 10 Sample Argument Map Project Kristof’s “War & Wisdom” sets out to intervene in the debate about invading Iraq, and persuade policymakers and readers of The New York Times that war with Iraq would be a mistake. He does this by listing the most common arguments for going to war and constructing rebuttals for them, by documenting the concerns of key political and military authorities, and by showing that viable alternatives exist. Argument We should not go to war as it will cost too many lives and too much money, Hussein is not an imminent threat, and we have effective alternatives. Claim Claim Claim Claim Claim Key military authorities do not believe we need to invade Iraq Evidence for Claim War will cost too much in lives and money, and there are much better ways of spending the money. Evidence for Claim When faced with similar threats (Libya in the 80s, cold war) past presidents such as Reagan responded not by going to war but by pursuing a policy of containment. We can do more to bolster security by spending money on education and energy independence. Hussein doesn’t have nukes, and can’t develop them in the future as they are easy to detect. Evidence for Claim Evidence for Claim Evidence for Claim Quotations that document the position of Generals Schwarzkopf, Zinni and Clark Cites estimated costs + cost per family. Cites historical record of actions by Libyan regime and the response of president Reagan Strategies that support Strategies that support Strategies that support Selects key generals likely to appeal to a broad audience (republican and democrat) esp. one famous for planning the first Gulf war; a person who has directed war against Iraqi troops, and thus has much practical experience. Pathos appeals (“kids torn apart by machine-gun fire.”) Appeals to precedent, authority, & past successful policy (containment) Selects an analogy and draws on authorities likely to appeal to the broadest possible audience – particularly those suspicious of antiwar arguments. Uses analogy to construct powerful rebuttal of main claim for invasion. 11 Inspectors can find nukes, as need vast electrical hookups that are easily identifiable. Strategies that support Strategies that support Strategic concessions – Bush has shown Hussein is a liar, Iraq is hiding weapons, and we are thus “justified” in invading Iraq. But this would be very unwise and too costly. Assignment & Prompt ASSIGNMENT # 1: CONSTRUCTING AN ACCOUNT & ANALYSIS OF AN ARGUMENT Length 5 – 6 pages Due: Wednesday February 20 In “Small Change: Why the Revolution Will Not Be Tweeted,” Malcolm Gladwell argues against the idea that social media has radically altered the way people organize, protest, and create change. He suggests that the effects of social media activism – of using new media tools such as Facebook and Twitter to advance social change – have been wildly exaggerated. Published in the New Yorker magazine in October, 2010, Gladwell’s article claims that “social media can’t provide what social change has always required.” Successful Papers Will: 1. Describe Gladwell’s’ project and argument, and what you see as his most important or interesting claims, explaining how these relate to the main argument. 2. Analyze the ways in which he supports his claims, and the moves or strategies he employs to advance these claims. 3. Write the paper as if addressing a reader unfamiliar with Gladwell’s text. 4. Comment on how this text is significant—what difference it might make to readers. 5. Use an effective structure that carefully guides the reader from one idea to the next, and be thoroughly edited so that sentences are readable and appropriate for an academic audience. Key learning outcomes: students will be able to describe and analyze an author’s argument, claims, project, support and rhetorical strategies. Sample Assignment 1 Prompt Part 1. Introduction (1-2 paragraphs) 1. Introduce the author and his project. Questions to consider: a) Who is he? b) What is his project? (What sort of work does he set out to do, how, and why?) 2. Describe the author’s main argument - what is he trying to get us to believe? 3. State the direction of your analysis and the steps you will take to get us there (“metadiscourse.”) (E.g., “In my analysis of Gladwell’s text I will examine X and show Y.”) Part 2. The Body, in which you present your central analysis In this section, you will analyze 3 or 4 major claims that support the author’s argument. For each claim, you will: Identify the claim in your own words. Use quotations to illustrate this claim. Introduce, integrate and explain the quotations (see Graff et al,. 39 – 49). Identify the evidence the author presents to support this claim Identify a strategy, appeal, or some aspect of the organization/use of evidence, and discuss how this supports the claim/argument. Part 3: Your conclusion, which tells us “So What?” (2-3 paragraphs) In this section, you will discuss issues of significance or effectiveness. There are several things you can choose to emphasize in this section. What is the significance of the argument – why does it matter (at this moment/to you/in general)? Has the author impacted your thinking/views on this topic? If so, in what way? Consider the effectiveness of the argument – focus on a key strength or weaknesses 12 Outline for Introduction 13 Template Sentences for Strategy Section Introduction + overview of your project “A Rhetorical strategy is a particular way in which authors craft language so as to have an effect on readers. Strategies are means of persuasion, ways of using language to get readers’ attention, interest, or agreement. It is important to be able to identify these strategies so as to…” “In my paper I will begin by briefly describing the project and argument made by…” “I will then identify and examine some of the rhetorical strategies used by…Next, I will present an explanation of these strategies, explaining how they work and why they are used…Finally, I will conclude my paper with a discussion of the significance of these authors’ work [or] a comparison of their use of rhetorical strategies.” Project and Argument Statements: “In article X, Tannen, professor of linguistics at…investigates Y… Tannen’s project is A, or as she puts it “B, C and D.” Tannen uses several primary methods to achieve this, most notably E, F and G…” “Tannen’s central argument is H, or as she puts it, “Bla bla bla.” Tannen claims X is the case/advances argument Y/asserts Z.” Rhetorical Strategies: “Chua uses a number of rhetorical strategies throughout her text. However, I will focus on J and K, which appear in her discussion of L…” “A clear example of this strategy occurs on page iv, when Chua states… This strategy works by doing C…it is effective because it does K…it has the effect of P… Why engage such a strategy? Chua chooses this strategy in order to…” “A second example of this rhetorical strategy is…” Conclusion: “The significance of Chua’s project can be discerned in F…She stresses the importance of Y, and argues that insufficient attention has been paid to Z…Chua claims that it is crucial that X… This paper demonstrates the value of H, and how by paying close attention to the way authors do J we can see T…” 14 Templates from They Say/I Say (From Graff et al., They Say/I Say: The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing.) HOME GROWN TEMPLATES 15 Quick Guide to Quotations (See Graff et al., “The Art of Quoting”) 1. Choose Carefully 2. Introduce or “frame” 3. Integrate 4. Explain and analyze 5. Always Cite 6. Maintain Your Voice (handle attributions) Choose what you want to use carefully. Make sure you need the quotation to illustrate your point, and that it connects closely with the point you are making. You should ‘set up’ or introduce quotations – don’t just insert them into your text without providing some background. This means they should be introduced with your own words. You should use introductory phrases that provide context or say what the author is doing in the section of the text the quotation comes from– for example, “Author X is concerned about global warming, and describes her alarm in the following terms. She writes, [insert quotation]… Make the quoted words fit the language (part of speech and verb tense) of your writing. You may need to carefully select parts of the quotation to do this. EXPLAIN the relevance of any direct quote you include to the analysis you’re doing within that paragraph or section. Never just leave a quote hanging on its own (aka the “dangling” or “drive-by” quotation, as Graff and Birkenstein put it.) Always cite the text, author, page number, etc. you are using.. Sometimes when a writer is paraphrasing the ideas of others the viewpoints get mixed up and the reader finds it difficult to know who is saying what. The writer needs to provide good "cueing" so that the reader always knows the difference between what the writer believes and what the source believes. QUOTATION SANDWICH Top slice = introduction & framing (advance your point or interpretation of the author’s claim, or what the author is doing) The meat/tofu = the actual quotation Bottom slice = explain, restate, discuss significance. Why is it important, and what do you take it to say? Quotations & Punctuation Commas and periods go INSIDE QUOTATIONS unless parenthetical citation follows, in which case the comma or period goes on the other side of the citation (note that in British English it’s the opposite – punctuation goes outside the quotation). "Really, there is no excuse for aggressive behavior," the supervisor said. "It sets a bad example." The period goes outside of the quotation mark when using a parenthetical reference. "Animals have a variety of emotions similar to humans" (Erikson 990). The colon and semicolon always go outside the closing quotation mark. He referred to this group of people as his "gang": Heidi, Heather Shelley, and Jessie. 16 Example of a Rhetorical Move: Metadiscourse 2 Many forms of academic writing utilize metadiscourse. These are moments in the text when the author explicitly TELLS you how to interpret her words. In academic texts, metadiscourse occurs when the author stops arguing, stands back and tells you how to interpret the argument. In this moment, the author reflects on what he or she is saying. This may involve making explicit the strategies (the strategy of explaining a strategy). Metadiscourse is similar to the project statement or thesis in your papers. Practicing writing metadiscourse is useful. It helps you develop your ideas, generate more text, and get a better sense of both your paper’s structure and how you might change direction. In clarifying things for your reader, you also clarify things for yourself. Gerald Graff describes the way this works in his article, “How to Write an Argument: What Students and Teachers Really Need to Know,” found in this reader. For specific examples, see They Say/I Say p. 126-30. Authors use metadiscourse to: 1. Ward off potential misunderstandings. 2. Anticipate and respond to objections. 3. Orient the reader by providing a “map”– where the argument is going, where it has gone, etc. 4. Forecast & review structure and purpose 5. Qualify the nature, scope or extent of an argument 6. Alert readers to an elaboration of a previous idea. 7. Move from a general claim to a specific example. 8. Indicate that a claim is especially important 2 From They Say /I Say 17